A HIGH PRIEST IN HELL

by Jeremy Chance Springfield

8/3/18

Yeshua never shied away from controversy. His words riled the crowds at times, eliciting emotions from people of all walks of life. His declarations and discipling of those who would hear were not always warmly received, but were often antagonistic and bombastic, revealing the true hearts of those who were present. But He never seemed to worry about the consequences of offending His countryfolk, for the truth needed to be shared, and with the power of the Holy Spirit vivifying His mind, He was blessed with the ability to know the needs and minds of those in His midst, sharing the information that would encourage the faithful and bring remorse to the guilty.

However, there is one time in particular where it seems He carefully chose how He would present the truth to His listeners. The importance of His message would not be downplayed, but certain key details had to be delicately presented, due to the unique nature of His message. The reason why will be explained in due time in this study, but the account itself need first be read and the elements of it highlighted so that we can appreciate His tact in delivery.

The account itself is recorded for us only in the book of Luke, in chapter 16:19-31. It is popularly known as the “Parable of the Rich Man and Lazarus.” The story in a nut-shell appears to be straightforward: a sick beggar seeks charity from a rich man who ignores him and seeks his own desires, but death eventually comes to both, and when the beggar is found at peace in the arms of Abraham, the rich man is instead tormented in the fires of the grave with no opportunity of relief. In itself, this account is of interest in that while it is preceded almost immediately in chapter 16 by a parable, it is never declared blatantly to be one by Messiah, and yet not long after, in chapter 18, another parable is begun. It has certain characteristics of a parable, and can be safely read as one, but it also has peculiar details about it that make it ultimately something much more than what is normally encountered in the rabbinic teaching methods of Yeshua: it is ultimately a prophetic parable.

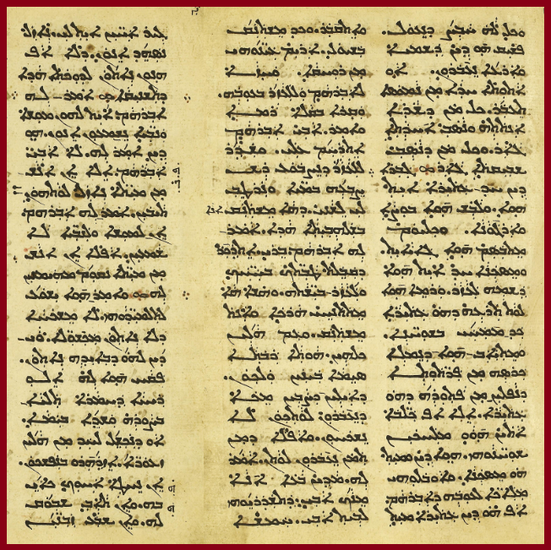

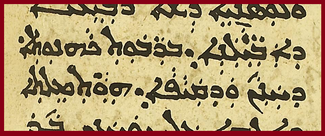

Let us take a moment now and read the text in its entirety, translated freshly from the ancient Aramaic of the Peshitta, so that we can appreciate why Yeshua was carefully cryptic in His choice of words when He delivered this message.

However, there is one time in particular where it seems He carefully chose how He would present the truth to His listeners. The importance of His message would not be downplayed, but certain key details had to be delicately presented, due to the unique nature of His message. The reason why will be explained in due time in this study, but the account itself need first be read and the elements of it highlighted so that we can appreciate His tact in delivery.

The account itself is recorded for us only in the book of Luke, in chapter 16:19-31. It is popularly known as the “Parable of the Rich Man and Lazarus.” The story in a nut-shell appears to be straightforward: a sick beggar seeks charity from a rich man who ignores him and seeks his own desires, but death eventually comes to both, and when the beggar is found at peace in the arms of Abraham, the rich man is instead tormented in the fires of the grave with no opportunity of relief. In itself, this account is of interest in that while it is preceded almost immediately in chapter 16 by a parable, it is never declared blatantly to be one by Messiah, and yet not long after, in chapter 18, another parable is begun. It has certain characteristics of a parable, and can be safely read as one, but it also has peculiar details about it that make it ultimately something much more than what is normally encountered in the rabbinic teaching methods of Yeshua: it is ultimately a prophetic parable.

Let us take a moment now and read the text in its entirety, translated freshly from the ancient Aramaic of the Peshitta, so that we can appreciate why Yeshua was carefully cryptic in His choice of words when He delivered this message.

19 Yet, one wealthy man there was, and he was clothed with fine linen, and purple, and every day was haughtily merry.

20 And one poor man there was, whose name was La‘azar, and he was cast toward the door of he who was wealthy while he was struck with abscesses.

21 And he craved that he should fill his belly from the crumbs that would fall from the money-changing table of he who was wealthy, and even the dogs came, licking his abscesses.

22 Yet it was, and the poor man died, and the messengers led him to the bosom of Awraham; yet also, he who was wealthy died, and was buried.

23 And while oppressed in Sheol, he lifted his eyes from afar, and saw Awraham, and La‘azar on his bosom.

24 And he cried with a loud voice, and said, ‘My father Awraham! You must have compassion upon me, and you must send La‘azar, that he should dip the tip of his finger in the waters, and moisten for me my tongue, for see! I am oppressed in this flame!’

25 Awraham said to him, ‘My son, you must remember that you received your good in your life, and La‘azar his evil, and now, see! he rests here, and you are oppressed!

26 And with these all, there is a great gap between us, and those of them who desire from here that they should cross over to you are not able, and also none of them from there shall cross over to us.’

27 He said to him, ‘Then, I request from you, my father, that you should send to the house of my father,

28 for five brothers there are to me. You must let him go to witness to them, that they also shall not come to this place of oppression!’

29 Awraham said to him, ‘There is for them Mushe and the Prophets; they must hear them!’

30 Yet, he said to him, ‘No, my father Awraham; but instead, if a man from the dead shall go to them, they shall turn back!’

31 Awraham said to him, ‘If unto Mushe and unto the Prophets they shall not hear, also neither if a man should rise from the dead would they believe him!’”

20 And one poor man there was, whose name was La‘azar, and he was cast toward the door of he who was wealthy while he was struck with abscesses.

21 And he craved that he should fill his belly from the crumbs that would fall from the money-changing table of he who was wealthy, and even the dogs came, licking his abscesses.

22 Yet it was, and the poor man died, and the messengers led him to the bosom of Awraham; yet also, he who was wealthy died, and was buried.

23 And while oppressed in Sheol, he lifted his eyes from afar, and saw Awraham, and La‘azar on his bosom.

24 And he cried with a loud voice, and said, ‘My father Awraham! You must have compassion upon me, and you must send La‘azar, that he should dip the tip of his finger in the waters, and moisten for me my tongue, for see! I am oppressed in this flame!’

25 Awraham said to him, ‘My son, you must remember that you received your good in your life, and La‘azar his evil, and now, see! he rests here, and you are oppressed!

26 And with these all, there is a great gap between us, and those of them who desire from here that they should cross over to you are not able, and also none of them from there shall cross over to us.’

27 He said to him, ‘Then, I request from you, my father, that you should send to the house of my father,

28 for five brothers there are to me. You must let him go to witness to them, that they also shall not come to this place of oppression!’

29 Awraham said to him, ‘There is for them Mushe and the Prophets; they must hear them!’

30 Yet, he said to him, ‘No, my father Awraham; but instead, if a man from the dead shall go to them, they shall turn back!’

31 Awraham said to him, ‘If unto Mushe and unto the Prophets they shall not hear, also neither if a man should rise from the dead would they believe him!’”

The most-often cited reason for viewing it as something other than a parable is that a character in the account is specifically named – Lazarus (La‘azar in the Aramaic). While several parables of Yeshua are peopled with all kinds of characters, none of them are ever given names. In this passage only is a seeming parable shared with a person decisively named. That detail makes this stand out as possibly more than a parable, and I would think it is right to note that nuance as important. The reason not to just relegate it as an oddity in the oral ministry of Yeshua is that there is a person with the name Lazarus who features quite significantly in the ministry of Yeshua. Not only is a Lazarus a part of Yeshua’s ministry (along with his sisters, Mary and Martha), but Lazarus’ part to play in it all is directly related to the account here in that he dies from an undisclosed sickness and is raised from the dead four days later by the oral command of Yeshua (see John 11:1-46 for the entire account)! These two prominent factors make it hard to readily judge the account as mere parable and move on. Rather, these factors should serve as signals to pay attention closely to the text, for it is full of deeper insights than what we would assume from a surface reading of the account.

If we approach this account as portraying real people, even if it is in a parable style, and we seek to understand the deeper meaning intended, then we must understand the identity of the main character in the story. In fact, there are three characters in the forefront of the story: the rich man, Lazarus, and Abraham (the five brothers are important in themselves for reasons to be explained, but are not the main characters). It is of interest that of the three main characters, Lazarus is named, and Abraham is named, but the initial character of the account, and arguably the most important to the story, is left nameless.

If we approach this account as portraying real people, even if it is in a parable style, and we seek to understand the deeper meaning intended, then we must understand the identity of the main character in the story. In fact, there are three characters in the forefront of the story: the rich man, Lazarus, and Abraham (the five brothers are important in themselves for reasons to be explained, but are not the main characters). It is of interest that of the three main characters, Lazarus is named, and Abraham is named, but the initial character of the account, and arguably the most important to the story, is left nameless.

The traditional view of the identity of this rich man leaves us no better than not knowing his name. While the majority of Greek manuscripts of Luke tell us only that the person was a “rich man,” we do have the witness of manuscript p75 that in its curious variant reading, gives him a name: NEUES. Additionally, the Coptic-Sahidic gives a slightly different version of this: NIVEUES. Both are minor spelling variations of the Greek rendering of the name of the Assyrian city of Nineveh. There is nothing in the account in Luke to give any assumption that the name of this rich man was “Nineveh.” Indeed, the name of an ancient Assyrian city being the name of an individual would be rather odd even in a parable. How that name may have been arrived at is unanswerable. If that doesn’t make you scratch your head enough, we have the witnesses of a Pseudo-Cyprian and a Priscillian text that assert in unity that his name was Phineas. While Phineas is indeed a Hebrew name, and the final high priest before the destruction of the Temple was named Phannius (see Josephus’ The Jewish War, IV, III) there is nothing in the text to suggest such a name for the rich man, as that particular Phannius came into prominence only much-later in time at about 68 CE, and was formerly merely a poor stone-cutter with no knowledge of any Temple regulations, such that he would have likely otherwise been considered mentally deficient to hold any priestly duties, who was instead raised to the office of high priest by violent forces not of his choosing, and entirely against all known protocol for obtaining that office. The assertion seems entirely untenable. Again, the believer is left to wonder where such a name arose, and why it should be preferred over any other possibly given.

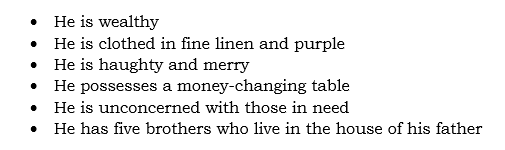

Therefore, unfortunately, none of these names serve to help illuminate who this rich man might have been in the actual pages of history. None of those three names fit any single person living in 1st century Israel in the context that is provided in the account spoken by Yeshua. Those names are historically vacuous for us, for no recorded individual by such a name meets the requirements presented to us in the account told us in Luke 16:19-31. The details of that story concerning the rich man that should be somehow met are these:

Therefore, unfortunately, none of these names serve to help illuminate who this rich man might have been in the actual pages of history. None of those three names fit any single person living in 1st century Israel in the context that is provided in the account spoken by Yeshua. Those names are historically vacuous for us, for no recorded individual by such a name meets the requirements presented to us in the account told us in Luke 16:19-31. The details of that story concerning the rich man that should be somehow met are these:

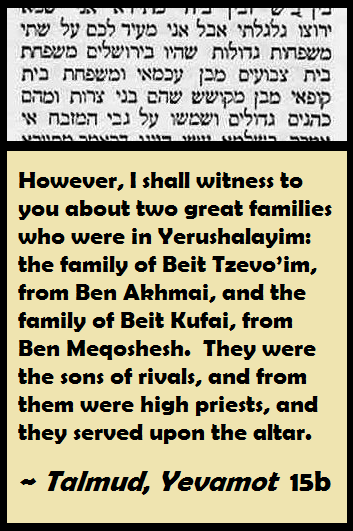

These are the details provided to us by Yeshua concerning the identity of the rich man. While no specific name is given for him, if we pay close attention to these clues in the text of the story at hand, and carefully consider the known history and immediate societal situation of Yeshua’s time, things become far clearer to us in our search for an answer to the identity of the rich man, which will in turn help us to appreciate why Yeshua spoke cryptically in this instance. The truth of the matter is that there was a man alive at the time Yeshua spoke these very words who would have fit the details mentioned in the story given to an amazing degree! The man who officiated as High Priest during the time of Yeshua’s ministry was named Caiaphas (Qayafa in the Aramaic). The Gospels record his words and actions concerning Yeshua and the events that transpired which brought about the crucifixion. He was of a prominent priestly family in Jerusalem, as we see referenced in the Talmud Bavli, Yevamot 15b, where his name is rendered as Qufai, the Hebrew pronunciation of the Aramaic Qayafa.

As the High Priest, Caiaphas was commanded by the Torah to wear certain types of clothing to distinguish him from the rest of the priests, particularly, what was known as the ephod (like a mantle). The clothing of the high priest was of the highest value and befitted a man of prestige and wealth. This ephod that was distinct to the high priest’s attire is commanded in Exodus 28:6 to be made of “fine linen,” and one of the three colors it is to be dyed is “purple.” Interestingly, the Aramaic words found in the Peshitta for “fine linen” and for “purple” in this account from Luke 16 come from the same Aramaic terms that are encountered in the Aramaic of the Peshitta translation of Exodus 28:6, as well as the Aramaic translations of that same passage in the ancient Jewish Targums of Onqelos, Pseudo-Yonatan, and Neofiti! This linking of terms shows us that Yeshua was directly referencing the high priestly attire in the choice of words He used to describe the garments of the rich man. Knowing that Caiaphas was the officiating high priest at that time, it becomes apparent exactly whom Yeshua was referring to when He spoke of “one wealthy man” without giving him a name.

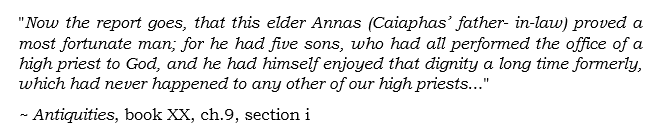

When the identity of the rich man is seen to certainly have been intended to be Caiaphas, and not some unheard-of individual named Neues / Niveues / Phineas, all the pieces of the puzzle start to fall into place in an astounding manner. The account tells us that the wealthy man in Sheol (Hell) declares to have “five brothers,” and he begs Abraham that Lazarus, who is safely reposing with Abraham, be sent to the house of his father so that they can be warned to turn away from their sinful lives. Now, Caiaphas was certainly the high priest, but his position was not one he inherited from his own father. Rather, history informs us that a high priest of a different family was in line and served prior to Caiaphas. That high priest’s name was Annas (Chanan / Chanin in the Hebrew, and sometimes recorded also as Ananus in the Greek). First-century Jewish historian Josephus, in his Antiquities of the Jews, records this of Annas:

When the identity of the rich man is seen to certainly have been intended to be Caiaphas, and not some unheard-of individual named Neues / Niveues / Phineas, all the pieces of the puzzle start to fall into place in an astounding manner. The account tells us that the wealthy man in Sheol (Hell) declares to have “five brothers,” and he begs Abraham that Lazarus, who is safely reposing with Abraham, be sent to the house of his father so that they can be warned to turn away from their sinful lives. Now, Caiaphas was certainly the high priest, but his position was not one he inherited from his own father. Rather, history informs us that a high priest of a different family was in line and served prior to Caiaphas. That high priest’s name was Annas (Chanan / Chanin in the Hebrew, and sometimes recorded also as Ananus in the Greek). First-century Jewish historian Josephus, in his Antiquities of the Jews, records this of Annas:

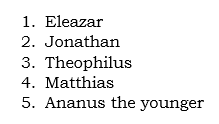

Rome deposed Annas from his position in 15 CE, putting in his place his son Eleazar, who served as high priest for two years. Rome again intervened after some time and circumstance and inserted the new-comer Caiaphas as the officiating high priest, who served as such from 18 to 36 CE. What is interesting, however, is that Caiaphas was married into the family of Annas, so that Caiaphas, upon his marriage, legally had five brothers! Those brothers were:

This detail aligns perfectly with the statement made by Yeshua in the story that the rich man proclaimed to have five brothers. The fact that Caiaphas was the high priest and was married into the family of Annas with his five sons, would have meant that the reference to “five brothers” by Yeshua was surely immediately understood by those in His presence to refer to one person only: the prominent Caiaphas.

The view of Annas as recorded in history is that he was not favorably received by the populace. His pompous wealth and supreme arrogance prevented him from releasing absolute control of his priestly power in the Temple after he was deposed by Rome, and instead continued to wield it over his sons (and son-in-law) in their subsequent officiating of the office, which, in turn, translated into perverse power held over all who came to the Temple. Therefore, this is the reason both Annas and Caiaphas are mentioned as being “concurrent” high priests in the priesthood, as declared in Luke 3:2 – an impossibility according to the Torah but made possible due to the fact that although Annas was deposed from his official position, he still held sway with his iron fist of authority over his sons and son-in-law, bending their experiences of officiating in the Temple to his own warped machinations.

The view of Annas as recorded in history is that he was not favorably received by the populace. His pompous wealth and supreme arrogance prevented him from releasing absolute control of his priestly power in the Temple after he was deposed by Rome, and instead continued to wield it over his sons (and son-in-law) in their subsequent officiating of the office, which, in turn, translated into perverse power held over all who came to the Temple. Therefore, this is the reason both Annas and Caiaphas are mentioned as being “concurrent” high priests in the priesthood, as declared in Luke 3:2 – an impossibility according to the Torah but made possible due to the fact that although Annas was deposed from his official position, he still held sway with his iron fist of authority over his sons and son-in-law, bending their experiences of officiating in the Temple to his own warped machinations.

In the high priesthood of Chanan and Qayafa…

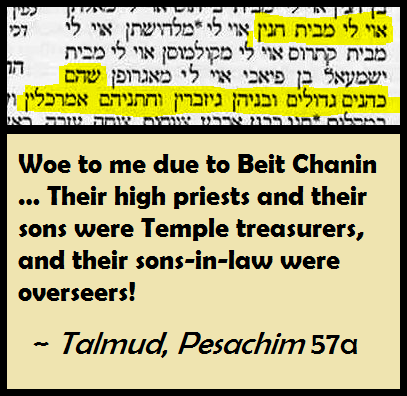

Annas orchestrated events in the Temple and in Jerusalem to the best of his ability through the acting authority of his son-in-law Caiaphas, who enjoyed his high priestly role for many years – a detail not typical of the time. This meant the populace endured the greedy spirit of the House of Annas and the House of Caiaphas for many long years. In fact, the Talmud Bavli, in Pesachim 57a, goes so far as to pronounce a woe over the House of Annas (spelled there as Chanin instead of Chanan) for the oppressive and manipulative control they held over the monetary aspects of worship in the Temple.

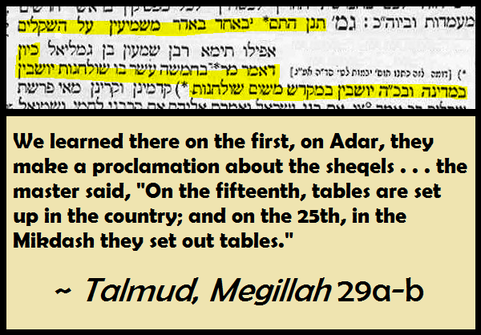

This control was exercised by the exploitation of what are popularly rendered as “bazaars” / “shops” in the Royal Stoa of the Temple grounds (called CHANUYOT BNEI CHANAN “shops of the sons of Annas” in Sifre Devarim 105:19 and CHANUYOT D’BNEI KHANAN “shops of the sons of Annas” in Talmud Yerushalmi, Peah 9b, and just CHANUYOT “shops” in Talmud Bavli, Rosh Hashanah 31a). This area is where commerce was engaged in by the worshipers who came to the Temple and the merchants present who would sell ritually-pure animals ready for sacrifice, as well as their official inspection, and where money-changing was also performed of the unfit Roman coins for the more expensive acceptable coin used in the Temple. This is the area where Yeshua made His jaw-dropping speech and scandalous cleansing, recorded for us in all the Gospels. It was also Yeshua’s unflinching disruption of this commerce in the Temple that caused the chief priests to actively seek to murder Him (see Luke 11:15-18), an option that had, up until then, been only a vocal declaration and plan by Caiaphas (see John 11:49:53). His ire in those shops was directed not at the mandated sacrifices or the exchange of common coin to holy half-shekels, as the Torah requires of us, but of the fact that Caiaphas (obeying the desires of Annas) effectively was holding hostage the natural worship experience in the Temple grounds by extorting the faithful to give more than they were required, or able, to give. These shops were not even originally situated in the Temple area all the time. Rather, the Talmud Bavli, in Megillah 29a-b, tells us that they only moved onto the Temple grounds during a specific time of the year (the springtime, right before Passover):

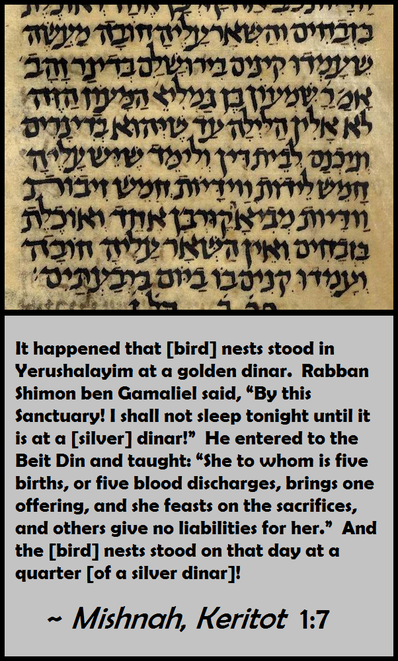

This placement of the money-changers there during the time of Passover was overseen by the House of Annas, and they made an enormous profit off the crowds of people coming to sincerely worship the Holy One – some for which it might have been the only time during the year that they could afford to leave home and business to appear before the Holy One, bringing with them not only what was needed for Passover, but also any particular sacrifices required of them due to circumstance or sin in the times since their last Temple visit. Under the hand of Caiaphas and his father-in-law, they were prone to raise the prices of the ritually pure animals, so that worshipers who were unable to bring their own acceptable animals in accordance to the Torah were forced to purchase them at the exorbitant prices set by Annas’ greedy desires. In fact, the Mishnah, Keritot 1:7, records an instance of just such price-gouging that happened several decades after Yeshua’s “Temple tantrum,” and what one teacher did to put an end to that unrighteous elevation of value.

The bird nests of which this passage speaks are in reference to the two birds that are to be brought for sacrifice according to the Torah after a woman has given birth or has experienced her monthly flow. The Mishnah tells us in this passage that they had risen in price to the unacceptable valuation of a golden dinar (denarius), when in truth such birds were typically less than a silver dinar (Yeshua rightly mentions in Matthew 10:29 that they should cost an assarion, which would be approximately the value of one-quarter of a silver dinar, as the Mishnah expresses was the price to which they ultimately fell due to Rabban Shimon’s intervention). As the Mishnah’s recorded event took place decades after Yeshua’s much more vocal outcry, this shows that the actions of Yeshua when He cleansed the Temple were not taken to heart by the ruling priests, but the extortion was resumed like a plague upon the people.

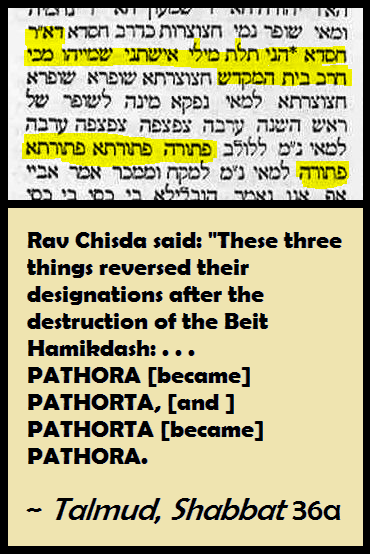

Since space was at a premium due to the influx of pilgrims there to worship during the holy days of Passover, these transactions occurred in the Royal Stoa shops of Herod’s Temple in the presence of trained merchants and inspectors who sat closely-packed at small tables where the money was exchanged for their particular services. The name given those tables was specific: PATHORA (small money-changing table). This is actually mentioned in the Talmud Bavli, Shabbat 36a, where it references how certain words changed meaning after the destruction of the Temple, and in the passage here quoted, mentions the change from PATHORA “money-changing table” to PATHORTA “generic table,” and vice versa.

Since space was at a premium due to the influx of pilgrims there to worship during the holy days of Passover, these transactions occurred in the Royal Stoa shops of Herod’s Temple in the presence of trained merchants and inspectors who sat closely-packed at small tables where the money was exchanged for their particular services. The name given those tables was specific: PATHORA (small money-changing table). This is actually mentioned in the Talmud Bavli, Shabbat 36a, where it references how certain words changed meaning after the destruction of the Temple, and in the passage here quoted, mentions the change from PATHORA “money-changing table” to PATHORTA “generic table,” and vice versa.

The word for “money-changing table” PATHORA is the exact same word that is used by Yeshua in the Peshitta’s Aramaic account of the rich man and how Lazarus would sit at the door of his house and desired to receive something from his “table.” I have translated the Aramaic term in the account from Luke 16 as “money-changing table” to reflect that context of the high priest and the transactions overseen by him in the Royal Stoa. Essentially, what Yeshua attempted to convey with that mention of such a table in the Aramaic is that with all the price-gouging going on at the money-changing tables overseen by Caiaphas, he had more than enough in his coffers to give at least some small sum to Lazarus, yet he did not. There is even the possibility that the mention of “the door of his house” was a reference to the Temple itself and the inability for Lazarus to actually enter inside due to the uncleanness his illness brought him (the Peshitta says that he suffered from SHUKHNE’ “abscesses,” which is merely the Aramaic cognate for the Hebrew word that appears in the Torah – SHEKHIN – that references the sores on a leper.

The story ends by having the rich man in Sheol (Hell) be denied his request that Lazarus be sent from his place in paradise back to earth on the basis that if someone is ignoring the witness of the Torah and the Prophets, they will neither heed the witness of someone who has been raised from the dead. The idea that Caiaphas had judgment awaiting him after death was itself a powerful slap in the face of the priests – many of whom were Sadducean, and in that position, denied any experience for man of an afterlife. Thus, the presentation of a “wealthy man” / high priest / Caiaphas enduring the afflictions of Hell would have been a scathing insult just by itself.

This statement of the rich man in torment seeking help from a dead man in Paradise who would be raised to warn his family was spoken in prophetic tones, for not long after this would we see the actual Lazarus himself who was an important person in the ministry of Yeshua end up dying from some type of sickness, and four days later, be then miraculously raised by the merit of Yeshua. Furthermore, the prophetic detail of the resurrection of Lazarus in this story by Yeshua is heightened by the fact that after his literal resurrection, Lazarus himself was sought to be murdered by the decision of the chief priests (Annas, Caiaphas, and likely Jonathan, son of Annas and successor of Caiaphas, mentioned together with the former two men in Acts 4:6), mentioned in John 12:10-11, for his witness turned more and more Jews to trust in the testimony of Yeshua. This detail clearly shows that they did not listen to the words of one who had risen from the dead, proving the words of the Messiah to have been absolutely accurate in His teaching!

All of this information about the identity of the rich man and its importance can be finalized with another detail not typically considered in our studies: to whom was Luke writing? While it may seem like an unimportant question, the answer gives yet another reason to firmly believe that Caiaphas was the intended individual behind the veiled reference to a “wealthy man” by Yeshua. Luke 1:3 tells us that he wrote his Gospel text orignally for the eyes of just one person – a man named Theophilus. This was not a small undertaking, yet Luke’s immense investigation of the life and ministry of Yeshua was indeed intended for a man who is mentioned only twice in all the New Covenant writings: Theophilus. That second mention is again by Luke, in Acts 1:1, which tells us that his chronicle of the deeds of Yeshua’s closest followers immediately after the ministry of Yeshua was written also to Theophilus.

Who was this individual? What made him so important that Luke set out to write down everything he knew about the ministry of Yeshua and the subsequent spread of His message to this one individual? The answer may be surprising, but is entirely relevant to the topic of this study!

The most logical identification of the addressee of both Luke and Acts is a man named Theophilus ben Ananus, encountered previously in this study as one of the five sons of Annas / Ananus, who himself eventually served as high priest for several years after the short officiation of his brother Jonathan, who served right after Caiaphas. It would make sense furthermore in that Luke was present with Paul during his appearance before the council in Acts 22:30 – 23:9, of which consisted not only of the chief priests, but also Theophilus’ brother and then-functioning High Priest, Ananus the younger (officiated in 63 CE, and unofficially so behind-the-scenes until his murder in 68 CE). It would make total sense that Luke’s contact with the chief priests during that explosive and confusing council would have put him in the situation to produce the lengthy chronicles for the former High Priest Theophilus so he could make up his own mind about the matters that were fueling the uncharacteristic actions of the Pharisee named Paul. And finally, it would make sense that Theophilus ben Ananus is the Theophilus named in Luke and Acts due to how Luke greets him in Luke 1:3 – with the term “illustrious.” Interestingly, in the ancient Midrash Shir haShirim 2:13, the text uses the same descriptor of “illustrious” as we find in the Aramaic of Luke 1:3 to reference righteous priests: HANNATZOKHOTH NIRA BA’ARETZ “the illustrious ones appear on the earth,” and then clarifies among whom is being spoken of: MALKI TZEDEQ UMSHUAKH MILKHAMAH “Melchizedek and the [Priest] Anointed for War.” It would therefore make sense that Luke would refer to a High Priest of Israel with such respectful a term as he does in the Aramaic, and why he would have spent so much time and effort in collating all the information about the life and ministry and subsequent events of Yeshua and His students.

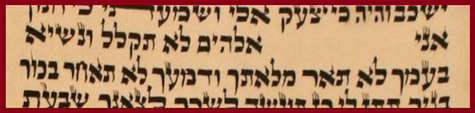

When we consider all of these factors about the identity of the rich man in the account given by Yeshua, we can see that had He named the High Priest Caiaphas as the rich man in torment in flames of Sheol (Hell), He would have been possibly viewed as guilty of speaking ill against an officiating high priest of Israel, which would have directly transgressed Exodus 22:28 and its declaration not to speak a curse against a leader:

Who was this individual? What made him so important that Luke set out to write down everything he knew about the ministry of Yeshua and the subsequent spread of His message to this one individual? The answer may be surprising, but is entirely relevant to the topic of this study!

The most logical identification of the addressee of both Luke and Acts is a man named Theophilus ben Ananus, encountered previously in this study as one of the five sons of Annas / Ananus, who himself eventually served as high priest for several years after the short officiation of his brother Jonathan, who served right after Caiaphas. It would make sense furthermore in that Luke was present with Paul during his appearance before the council in Acts 22:30 – 23:9, of which consisted not only of the chief priests, but also Theophilus’ brother and then-functioning High Priest, Ananus the younger (officiated in 63 CE, and unofficially so behind-the-scenes until his murder in 68 CE). It would make total sense that Luke’s contact with the chief priests during that explosive and confusing council would have put him in the situation to produce the lengthy chronicles for the former High Priest Theophilus so he could make up his own mind about the matters that were fueling the uncharacteristic actions of the Pharisee named Paul. And finally, it would make sense that Theophilus ben Ananus is the Theophilus named in Luke and Acts due to how Luke greets him in Luke 1:3 – with the term “illustrious.” Interestingly, in the ancient Midrash Shir haShirim 2:13, the text uses the same descriptor of “illustrious” as we find in the Aramaic of Luke 1:3 to reference righteous priests: HANNATZOKHOTH NIRA BA’ARETZ “the illustrious ones appear on the earth,” and then clarifies among whom is being spoken of: MALKI TZEDEQ UMSHUAKH MILKHAMAH “Melchizedek and the [Priest] Anointed for War.” It would therefore make sense that Luke would refer to a High Priest of Israel with such respectful a term as he does in the Aramaic, and why he would have spent so much time and effort in collating all the information about the life and ministry and subsequent events of Yeshua and His students.

When we consider all of these factors about the identity of the rich man in the account given by Yeshua, we can see that had He named the High Priest Caiaphas as the rich man in torment in flames of Sheol (Hell), He would have been possibly viewed as guilty of speaking ill against an officiating high priest of Israel, which would have directly transgressed Exodus 22:28 and its declaration not to speak a curse against a leader:

You shall not take Elohim lightly, and a leader in your people you shall not curse.

Had Yeshua spoken of the then-officiating High Priest as going to Hell and suffering its torments, He would have been liable for such a statement as a curse over the one who was viewed as being ordained by decision of Heaven. To utter such a thing would have meant transgression of the Torah as well as legal repercussion that would have brought a valid charge against Him during His later trial before Caiaphas himself. Instead, Yeshua was not yet ready to experience arrest and trial, for He still had necessary miracles to perform and teaching to provide to the people. Naming Caiaphas outright would have provoked those who were seeking anything to use against Him unnecessarily.

These things show us that Yeshua taught the truth He needed to share in prophetic words and did so without incriminating Himself prematurely. He displayed tact and wisdom in sharing the hard truths in such a way that all knew to whom He referred, but none could condemn Him as outright speaking against the corrupt high priest. He showed Himself as unafraid of the ire His words might bring, but aware of the limits He still had to abide by as a Torah-observant Jewish man. Our Messiah was not reckless in how He taught, but presented Himself in His ministry with clever and sagacious care. In this amazing story is an example from our Messiah on how to tell the hard truths while staying inside the safe borders the Torah has prescribed for us to operate within as a people.

These things show us that Yeshua taught the truth He needed to share in prophetic words and did so without incriminating Himself prematurely. He displayed tact and wisdom in sharing the hard truths in such a way that all knew to whom He referred, but none could condemn Him as outright speaking against the corrupt high priest. He showed Himself as unafraid of the ire His words might bring, but aware of the limits He still had to abide by as a Torah-observant Jewish man. Our Messiah was not reckless in how He taught, but presented Himself in His ministry with clever and sagacious care. In this amazing story is an example from our Messiah on how to tell the hard truths while staying inside the safe borders the Torah has prescribed for us to operate within as a people.

All study contents Copyright Jeremy Chance Springfield, except for graphics and images, which are Copyright their respective creators.