MASHIACH BAT AVICHAYIL

by Jeremy Chance Springfield

3/1/19

Throughout the pages of Hebrew Scripture, we find recorded the lives of several individuals who have traits and characteristics that strongly parallel the nature and life of the Messiah Yeshua. Just a few examples of the more popular ones would be Isaac, Joseph, and David. Lesser known candidates would include examples like Melchizedek, Bezalel, and Boaz. The lists, of course, could go on, as there are many legitimately fascinating parallels between individuals from all different portions of Scripture.

Each individual portrays Messianic traits in different ways. Some have parallels of the Messiah in His suffering role (known in Judaism as Mashiach ben Yosef “Messiah son of Joseph”), while others have parallels of the Messiah in His triumphant role (known as Mashiach ben David “Messiah son of David”). Each one uniquely shows themselves as essentially a messiah figure for their time, prophetically living a life that pointed to the future Redeemer.

Each individual portrays Messianic traits in different ways. Some have parallels of the Messiah in His suffering role (known in Judaism as Mashiach ben Yosef “Messiah son of Joseph”), while others have parallels of the Messiah in His triumphant role (known as Mashiach ben David “Messiah son of David”). Each one uniquely shows themselves as essentially a messiah figure for their time, prophetically living a life that pointed to the future Redeemer.

|

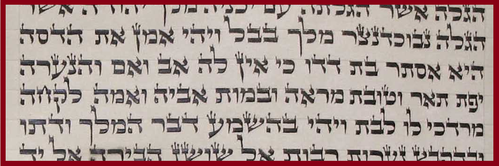

There is one person, however, who is rarely brought up as having a profoundly Messianic role, which is ironic, because the details surrounding this person, when examined carefully, show someone who is distinctly Messianic in tone. This person is also of unique position in the long and winding list of candidates in the Hebrew Scriptures in that this one is a female, and not a male! Her identity is none other than Hadassah bat Avichayil (Hadassah, daughter of Abihail). She is more popularly known as Queen Esther, of course, and her story and powerfully Messianic role is recorded for us in all its wonder and intrigue in the book of her own name.

|

Now, admittedly, upon first consideration, Esther as a Messianic figure might seem like a stretch: a Persian queen who appears to traditionally be reluctant to assume responsibility for her people in the face of danger doesn’t quite fit the narrative of a Messiah who marched steadfastly to the cross to secure redemption. She is hidden behind a mask of Persian assimilation – or so it seems. It is only upon closer inspection of the texts that the true parallels become startlingly clear, and the links established display a valid and emotional portrait of our Messiah in the actions of the unlikely Queen.

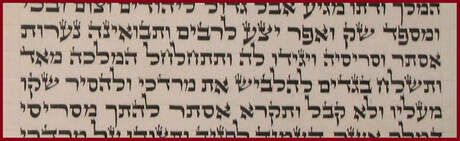

This is best accomplished by first appreciating the truly complex nature of the book of Esther. Judaism and most of Protestant Christianity accept the book and its contents as they have come to us from its Hebrew source. However, this situation is of particular interest, in that the text in use is admitted by Judaism, in the Talmud, Bava Batra 15a to have been compiled into its finished form by the holy men of the Great Assembly (Ezra, Mordechai, and those who were confederate with him at the return of Judah from the Babylonian exile in Ezra 2:2). However, the book is accepted by Catholic churches, based off the Greek Septuagint, in a slightly different form. The Septuagint’s version of Esther is not exactly a translation, but a unique retelling of the events recorded in the book of Esther that have several notable new details included. In addition to this, the Latin version of the book of Esther, as translated from the Hebrew by Jerome, is also a subtly different telling – incorporating the Hebrew and the Septuagint readings into a whole new final product. Interestingly, the Septuagint and the Latin texts that differ so much from the Hebrew are supplemented by details about the events recorded in Esther that are only elsewhere preserved in ancient Jewish Talmudic, midrashic, and historical texts! This yields a truly odd situation for the nature of the content of the book of Esther. To fully appreciate the information that has been preserved for us concerning the complete portrait of events that happened in the book, one needs to carefully utilize the several different ancient texts that address all the details concerning the account of Esther.

Anyone familiar with the sacrifice of Yeshua will recall that it all took place on the festival of Passover. His grim suffering and cruel crucifixion framed the memorial in a bloody perspective: The Messiah was laying down His life to rescue men from the death sentence of sin during the holy days of Passover!

This is exactly what we see in the person of Esther as recorded in the Biblical events that gave us the festival of Purim. While the festival of Purim itself is commemorated each year on the last month of the Jewish calendar in Adar (or Adar II on leap years), most of the events that are recorded for us in the book of Esther actually occurred on the Passover that preceded it that year! The dates are all listed in the text and show us that the honoring of Mordechai over the wicked Haman, the wine feast involving Esther, King Ahasuerus, and Haman, and the subsequent execution of Haman all happened on or during the Passover holiday!

This is exactly what we see in the person of Esther as recorded in the Biblical events that gave us the festival of Purim. While the festival of Purim itself is commemorated each year on the last month of the Jewish calendar in Adar (or Adar II on leap years), most of the events that are recorded for us in the book of Esther actually occurred on the Passover that preceded it that year! The dates are all listed in the text and show us that the honoring of Mordechai over the wicked Haman, the wine feast involving Esther, King Ahasuerus, and Haman, and the subsequent execution of Haman all happened on or during the Passover holiday!

With these factors understood, we can now begin to see the amazing parallels between Yeshua the Messiah and Queen Esther in her own profoundly Messianic role.

The tale tells us the wicked Haman sought to exterminate the Jewish population of Persia, and the date was set with divination and made known to all the kingdom so they could prepare and participate in the vile racial cleansing. When Mordechai found out, he made sure that word of it reached the ears of Esther in the relative safety of the royal palace. What happened next sets the stage for appreciating the Messianic role and parallels to be found in the person of Queen Esther.

We read that Mordechai gave Esther a directive on how she should react to this horrific turn of events in Esther 4:8.

The tale tells us the wicked Haman sought to exterminate the Jewish population of Persia, and the date was set with divination and made known to all the kingdom so they could prepare and participate in the vile racial cleansing. When Mordechai found out, he made sure that word of it reached the ears of Esther in the relative safety of the royal palace. What happened next sets the stage for appreciating the Messianic role and parallels to be found in the person of Queen Esther.

We read that Mordechai gave Esther a directive on how she should react to this horrific turn of events in Esther 4:8.

…to tell her, and to command her to go unto the king, to ingratiate [herself] to him, and to entreat before him concerning her people.

This begins the core of the Messianic parallels between Esther and Yeshua. It is a bit involved in how it is to be understood, so I urge the reader to be attentive of how the following passages all fit together to display an astonishing Messianic trait in the character and actions of Esther. Her response to Mordechai is vital to our understanding of her inherent Messianic nature. She explains her unique situation in 4:11.

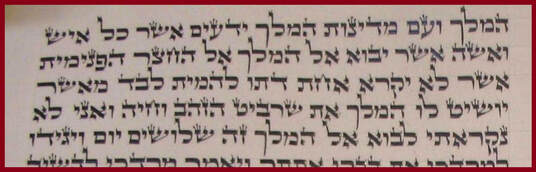

… whomever of any man or woman, who comes unto the king, unto the inner court, who is not summoned, has one law: to die – except to whom the king shall extend the golden scepter, and he shall live. Yet, I have not been summoned to come unto the king these [last] thirty days!

Esther was the queen, yet in this function she did not possess a royal authority that allowed her open access to the king. Rather, she was under the same restriction as others. If she came unbidden to the throne-room, her life hung upon the whim of the king. The opening scene of the book of Esther goes to great length to showcase the deadly whimsy of the Persian king Ahasuerus. His first wife, Vashti, was summarily removed due to failing to comply with the whimsical royal desire. Her replacement, Esther, was no less safe from the capricious decisions of the king. She thus had to play it careful in her interactions with Ahasuerus. Her wariness to approach the throne-room is thus entirely understandable, given the apparently delicate royal atmosphere.

But there was also something more to her hesitancy, and it is brought out only after Mordechai responds to her about the reach of this deadly edict against the Jews of Persia, recorded in Esther 4:13-14.

But there was also something more to her hesitancy, and it is brought out only after Mordechai responds to her about the reach of this deadly edict against the Jews of Persia, recorded in Esther 4:13-14.

13 Then Mordekai said to respond to Esther: “Do not think in your soul to escape [in] the House of the King more than all the Yehudim!

14 For if you are certainly silent at this time, respite and salvation shall rise for the Yehudim from another place, and the house of your father shall be lost. And who knows if for a time as this you have come to the kingdom?”

14 For if you are certainly silent at this time, respite and salvation shall rise for the Yehudim from another place, and the house of your father shall be lost. And who knows if for a time as this you have come to the kingdom?”

This response from Mordechai rocked Esther. It illuminated the path she would have to take, and it would not be an easy one. What Mordechai commanded of her could not have been more dangerous. She was told by him to “ingratiate herself” to the king in order to hopefully find a mercy for her people. This would require more from her than she ever thought she would have to give. Her response in Esther 4:16 highlights this fact.

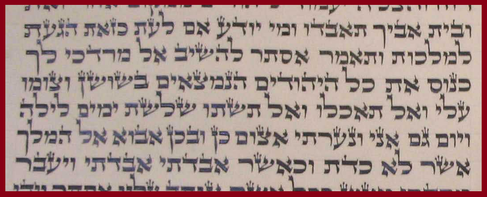

"Go, gather all the Yehudim who are present in Shushan, and they must fast concerning me, and they shall not eat, and they shall not drink three days – night and day! Even I and my maidens shall fast so. And in such I shall go unto the king, which is not as customary, and if I shall be lost, I shall be lost.”

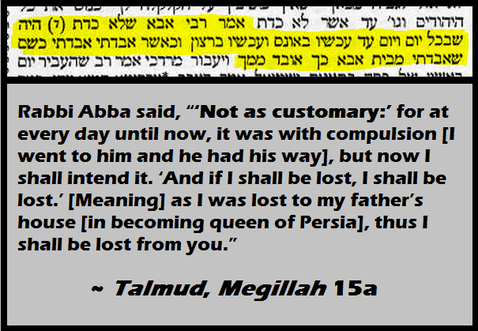

The gravity of the situation cannot get higher. Her plight is as bad as it comes. What Mordechai has asked is beyond all expectations. This is made clearer when we see the passage somewhat explained in the Talmud, again in tractate Megillah 15a.

The Talmudic text tells us that Esther had always went to the king only under royal request. She was compelled to do so by law. Appearing before Ahasuerus outside of royal request was potentially deadly. Therefore, appearing uninvited was a huge risk. However, there was more going on, if we pay attention to the way the Talmudic explanation is worded. She is said to have meant that she could be lost “to you.” What does this mean? To whom would she be lost? Well, the Biblical text tells us that her response was intended directly for Mordechai, so her loss would be to him. What is being conveyed by this information?

This is where the typical understanding of the plight of Esther radically alters by appreciating the account in its ancient Jewish perspective. What Esther was fearing facing was not just death but being lost entirely to the Jewish people and the rewards of the world to come. The ultimate sacrifice was being set before her. Why this is the case is because Esther was understood to actually be married first to Mordechai! True, she was his cousin, but marriage between cousins is not forbidden according to the Torah of the Holy One. Unfortunately, by the way the text of Esther 2:7 is usually translated, many people think otherwise – that she was the adopted daughter of Mordechai. However, the reality is much different.

This is where the typical understanding of the plight of Esther radically alters by appreciating the account in its ancient Jewish perspective. What Esther was fearing facing was not just death but being lost entirely to the Jewish people and the rewards of the world to come. The ultimate sacrifice was being set before her. Why this is the case is because Esther was understood to actually be married first to Mordechai! True, she was his cousin, but marriage between cousins is not forbidden according to the Torah of the Holy One. Unfortunately, by the way the text of Esther 2:7 is usually translated, many people think otherwise – that she was the adopted daughter of Mordechai. However, the reality is much different.

And he brought up Hadassah, (she is Esther) daughter of his uncle: for there was not for her father nor mother, and the maiden was beautiful and of good appearance; and at the death of her father and mother, Mordekai took her to himself for a daughter.

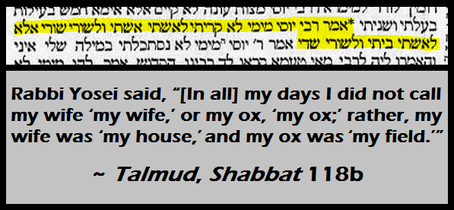

The term translated as “brought up” here is the Hebrew OMEYN, and literally means “to be faithful to.” Additionally, the text tells us that Mordechai “took her to himself for a daughter.” Here, the Hebrew phrase is actually telling us something different than we think. The phrase “took her” is overwhelmingly used in Scripture to refer to a man getting married (see Genesis 34:2, 38:2; 2nd Samuel 11:4, 13:11; 2nd Chronicles 11:20; Mark 12:21; Luke 20:30). Finally, the term BAT “daughter” here is not meant to be understood as such, but rather, as the word BEIT “house.” This aspect requires a little bit of explanation. The answer is that in ancient Hebraic usage, the word “house” was a euphemism for “wife” in many instances. Take, for example, this admission of a rabbi, as recorded in the Talmud, tractate Shabbat 118b.

Such a seemingly bizarre euphemism is repeated many times in ancient Jewish literature. Other examples from the Talmud itself are found in tractate Gittin 52a, as well as in tractate Yoma 13a, where in repeated instances, the high priest’s wife is referred to simply as his “house.” Suffice it to say, it was apparently rather common to hear a man refer to his wife as his “house” in that she is the one who makes a home for a man. As to the pronunciation difference between BAT “daughter” and BEIT “house,” when one factors how easily dialect differences alter the pronunciation of the letter yod that appears in the middle of BEIT “house,” it becomes no surprise to find that the two distinct terms can be uttered with essentially identical phonetic result.

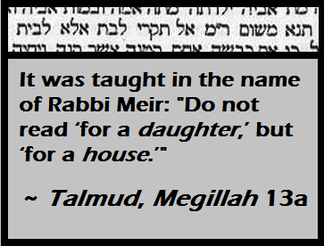

What this tells us is that Mordechai was legitimately the husband of Esther, and this view is actually the ancient and standard view of the situation held by Judaism. The Talmud again explains the reality of the matter in tractate Megillah 13a, where it is discussing the above passage from Esther 2:7.

What this tells us is that Mordechai was legitimately the husband of Esther, and this view is actually the ancient and standard view of the situation held by Judaism. The Talmud again explains the reality of the matter in tractate Megillah 13a, where it is discussing the above passage from Esther 2:7.

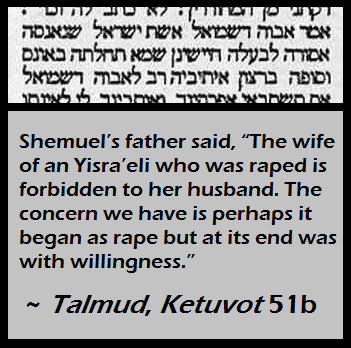

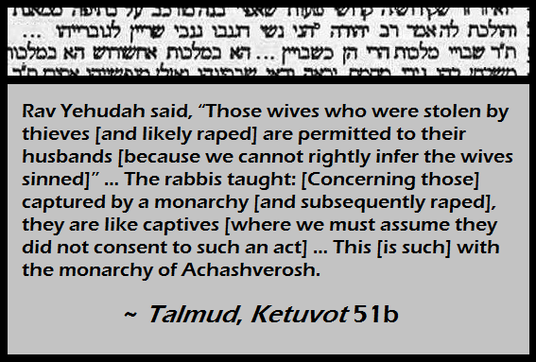

While it may seem initially odd to view Esther as the wife of Mordechai, the evidence from the Biblical text and the unanimous consensus of historical Hebraic thought shows us that she evidently was married to Mordechai. Therefore, when we have the proper ancient Jewish view of her marital status in the right place, it becomes immediately apparent that the situation Esther found herself in was not only a very difficult one, but that what she was really being asked to do by going to the Persian king was essentially the unthinkable. She was legally married to Mordechai, yet she had been taken by King Ahasuerus to be his bride, instead. This placed her into an unimaginable dilemma – if she were to obey the command of Mordechai her true husband, then she would be put into a situation where there was no good outcome for herself. It was a nightmare choice that confronted the Jewish woman, for it meant everything would change for her if she followed the command imposed upon her. The proposed legal situation she found herself in was horrific, as the Talmud, tractate Ketuvot 51b, explains for us.

The assertion here is that a woman who had been kidnapped and raped might have agreed to sexual relations with her captor at some point to save her life, and if that was the case, she was no longer to be viewed as entirely innocent, but willingly participating in an adulterous act. However, this proposal was rejected as not how such a situation was approached by legal rulings, as the tractate continues to explain for us.

The implications of these legal rulings mean that Esther’s placement in the royal palace and her sexual relationship with King Ahasuerus was viewed as her being a captive, and thus, any sexual event between them was considered rape towards her. This meant that she was still technically viewed as being faithful to Mordechai and could potentially be returned to him as a wife.

However, the command of Mordechai to Esther to “ingratiate herself” (Esther 4:8) to King Ahasuerus meant that she would be willingly putting herself at the sexual desires of the king by appearing before him without initially being summoned by him, and so she utters the words she does in Esther 4:16, which is why the Talmud interpreted them to mean that she would be lost “to you” – she would no longer be legally allowed to ever return to Mordechai! Mordechai was directing her to commit an act that would have her viewed as a sinner by everyone in order to potentially save the Jewish people from the deadly decree of Haman. Esther was being asked to willingly sacrifice herself and lay down her life for the well-being of her countrymen – by going willingly to the king she would be tainted with the colors of an adulteress and thus be forever marred, unable to return to Mordechai and rejoin her people as a pure woman of valor. In a heart-breaking action, we read that she willingly complied with the order given to her!

This is the key parallel to the Messiah, for Yeshua knowingly and willingly went to the cross. He actively laid down His own life when He could have saved Himself. (see my study: A LIFE LAID DOWN) Esther’s reaction to Mordechai’s command displays an astonishing determination to show her love for her people at the cost of her relationship with her Jewish husband and potentially even at the cost of her own life.

Once we have this sobering Messianic parallel understood, the other connections begin to fall into place in a surprising fashion. Esther will prove by the end of it to be one of the most Messianic of all individuals recorded in the Hebrew Scriptures.

A second link is found in the way the Hebrew text tells us Esther reacted initially to the news of the evil edict Haman connived against the Jewish people. In Esther 4:4, Mordechai’s initial explanation of what awaited them all receives an important reaction by the Jewish queen.

However, the command of Mordechai to Esther to “ingratiate herself” (Esther 4:8) to King Ahasuerus meant that she would be willingly putting herself at the sexual desires of the king by appearing before him without initially being summoned by him, and so she utters the words she does in Esther 4:16, which is why the Talmud interpreted them to mean that she would be lost “to you” – she would no longer be legally allowed to ever return to Mordechai! Mordechai was directing her to commit an act that would have her viewed as a sinner by everyone in order to potentially save the Jewish people from the deadly decree of Haman. Esther was being asked to willingly sacrifice herself and lay down her life for the well-being of her countrymen – by going willingly to the king she would be tainted with the colors of an adulteress and thus be forever marred, unable to return to Mordechai and rejoin her people as a pure woman of valor. In a heart-breaking action, we read that she willingly complied with the order given to her!

This is the key parallel to the Messiah, for Yeshua knowingly and willingly went to the cross. He actively laid down His own life when He could have saved Himself. (see my study: A LIFE LAID DOWN) Esther’s reaction to Mordechai’s command displays an astonishing determination to show her love for her people at the cost of her relationship with her Jewish husband and potentially even at the cost of her own life.

Once we have this sobering Messianic parallel understood, the other connections begin to fall into place in a surprising fashion. Esther will prove by the end of it to be one of the most Messianic of all individuals recorded in the Hebrew Scriptures.

A second link is found in the way the Hebrew text tells us Esther reacted initially to the news of the evil edict Haman connived against the Jewish people. In Esther 4:4, Mordechai’s initial explanation of what awaited them all receives an important reaction by the Jewish queen.

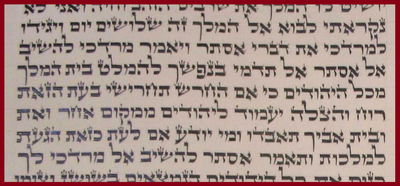

And the maidens and her eunuchs came [to] Estheyr, and they told her. And the queen was very distressed. And she sent garments to clothe Mordekai, and to take his sackcloth from upon him, and he did not accept them.

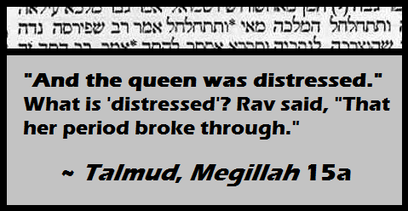

We see in this text that she reacted as one would expect – anguish seized her. However, the true nature of this detail was perceived from ancient times and is recorded in the Jewish writing of the Talmud in a way that explains the meaning of the odd wording preserved in the Biblical text. In tractate Megillah 15a, the word VATITHCHALCHAL “and she was distressed” is said to mean something quite surprising.

In the overwhelming intensity of her distress, we are told that Esther began to actually bleed! The stress of the knowledge caused a powerful physical reaction in her body, to the point that the rabbis understood that she started to menstruate! The implication is that she was placed under an astounding amount of physical pressure / distress for her body to begin to react so strongly to the situation. The concern she thus felt is clear from this detail.

This Talmudic assertion is not without basis, either. While it may seem strange to suggest this was Esther's reaction to the news, the Hebrew provides an interesting nuance that allows for such a proposal. The idea is arrived at by reading the Hebrew term of VATITHCHALCHAL “and she was distressed” as arising rather from the root of CHALAL “to be pierced” instead of the root CHUL “twist / distress.” The detail given here immediately brings to mind the plight of Yeshua as He prepared Himself to face the coming cross and its piercing nails.

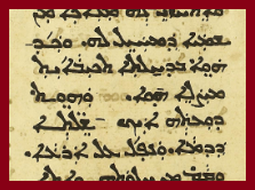

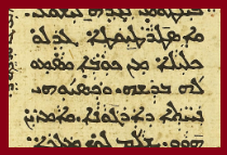

In the Peshitta’s Aramaic text of Luke 22:44, we actually read that a powerful distress came upon Him, as well, and His physical reaction is comparable to what is said concerning Esther.

This Talmudic assertion is not without basis, either. While it may seem strange to suggest this was Esther's reaction to the news, the Hebrew provides an interesting nuance that allows for such a proposal. The idea is arrived at by reading the Hebrew term of VATITHCHALCHAL “and she was distressed” as arising rather from the root of CHALAL “to be pierced” instead of the root CHUL “twist / distress.” The detail given here immediately brings to mind the plight of Yeshua as He prepared Himself to face the coming cross and its piercing nails.

In the Peshitta’s Aramaic text of Luke 22:44, we actually read that a powerful distress came upon Him, as well, and His physical reaction is comparable to what is said concerning Esther.

And while He was in fear, He forcibly prayed, and His sweat was as drops of blood, and He fell upon the ground.

Yeshua’s bodily stress level was such that He began to profusely sweat while He was engaged in prayer in the Garden of Gethsemane. While it is true that He did not actually sweat drops of literal blood, as some would have us to believe, the drops were “as” drops of blood – a parallel to what the Scriptures hint at with Esther’s reaction to the apparent fate that awaited the Jewish people. He too was incredibly distressed over the fate that awaited Him upon the cross. The fact that the term used to refer to Esther's distress also can be interpreted as "pierced" and was understood to refer to her beginning to bleed is an amazing Messianic parallel.

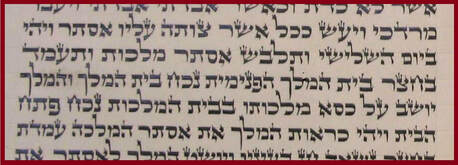

The third Messianic parallel in Esther’s actions is found in how the text of Esther 5:1 was understood. The Hebrew reads as follows.

And it came to be on the third day, that Esther was clothed royally, and she stood in the inner court of the House of the King, opposite the House of the King, and the King sat upon the throne of his royalty in the Royal House, opposite the door of the House.

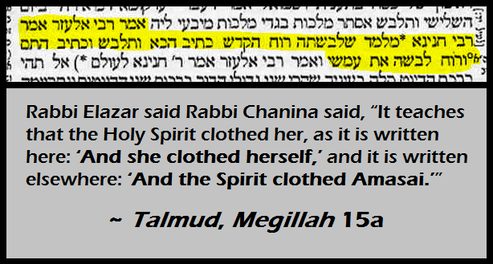

While it seems rather straightforward, the Hebrew uses the word MALKUTH “Kingdom” to refer to her “royal” clothes. The term MALKUTH, however, is established in Jewish mystical terminology to be another word for “the Holy Spirit,” so that when we read that she “was clothed royally,” we are really reading she was “clothed with the Holy Spirit.” Such a perception is recorded in the Talmud, tractate Megillah 15a, where we see also a further link to the Holy Spirit in that phrase.

The Talmud brings up as a secondary proof that this was really intended to mean that the Holy Spirit was coming upon her at this most important time, and does so by referencing 1st Chronicles 12:19 (18 in most English versions), where we read of Amasai coming to David, and it tells us that “the Spirit clothed” him in order for him to join the ranks of David’s men.

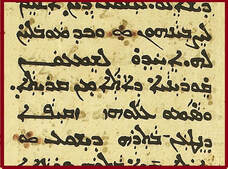

Therefore, since the Hebrew of Esther 5:1 uses the odd appearance of MALKUTH, which is understood to be a synonym for “the Holy Spirit,” it only made sense in the minds of the ancient teachers that for Esther to be clothed in MALKUTH meant that the Holy Spirit came upon her. This is paralleled to the Messiah as the Holy Spirit is also said to have come upon Him to empower Him to fulfill His Messianic role, and then we even read of Him speaking in the Aramaic of the Peshitta with the term MALKUTHI “My Kingdom” to Pilate in John 18:36, as He prepares to go to the cross.

Therefore, since the Hebrew of Esther 5:1 uses the odd appearance of MALKUTH, which is understood to be a synonym for “the Holy Spirit,” it only made sense in the minds of the ancient teachers that for Esther to be clothed in MALKUTH meant that the Holy Spirit came upon her. This is paralleled to the Messiah as the Holy Spirit is also said to have come upon Him to empower Him to fulfill His Messianic role, and then we even read of Him speaking in the Aramaic of the Peshitta with the term MALKUTHI “My Kingdom” to Pilate in John 18:36, as He prepares to go to the cross.

Yeshua said to him, “My own kingdom is not from this world. If this world was My kingdom, My ministers would have rioted that I should not be delivered to the Yihudaye. Yet, now, My kingdom is not from here.”

Then, just a few verses later in the text, we read in John 19:2 that Yeshua was given a royal robe to wear as mocking proof of His “kingship.”

And the soldiers intertwined a crown of briars, and set it on His head, and they covered Him with outer garments of purple.

In these we can see a fascinating link between Esther and Yeshua – they were both royalty, and both empowered by the Holy Spirit to perform the task required of them. Yeshua's outer garment robe was intended by the Romans as a mockery towards the claims made about Him, and yet, ironically, it symbolized the truth of His status - from the royal line of David, He is an heir to the throne of Israel. The purple garments show the spiritual reality even though it was physically a slap in the face towards Him.

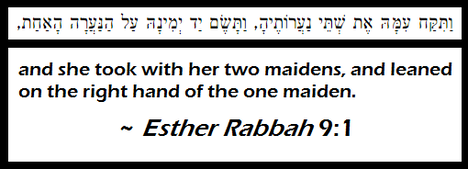

The fourth parallel is also perceived by looking at Esther 5:1 and how it was understood according to the Jewish midrashic literature. In Esther Rabbah 9:1, the ancient text gives us this detail about her appearance before King Ahasuerus.

Here we find that even though she was empowered by the Holy Spirit, the gravity of her situation weighed upon her in such a way that she needed help to reach her royal destination. It is likely that the thought of being lost to Mordechai and the rest of the Jewish people was too much for her to bear, so that she required aid to arrive at the throne-room. Such a mention shows how moved she truly was in wanting to be able to carry out the instructions given to her from Mordechai to appear before the king. Her physical anxiety would not prevent her from fulfilling the requirement laid before her. This detail is also mentioned in the Latin Vulgate’s version of Esther, as well as in the Greek Septuagint.

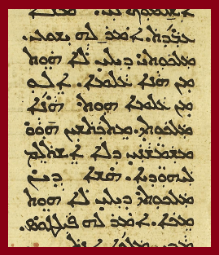

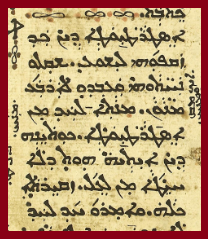

Similarly, we read that Yeshua’s trek to the site of the cross was also one wherein He needed the strength of another person in order to reach His grim destination. Luke 23:26 states the situation for us.

And while they took Him away, they seized Shemun Qurinaya, who came from the field, and they set upon him the cross, that he should lift it after Yeshua.

Simon of Cyrene was commanded by the Roman authorities to bear up the wood upon which the Messiah was soon to die because He was too weak to carry it Himself. Just as Esther needed an attendant to bear her up on her journey to the king, so too did Yeshua require someone to lift the cross-beam on His journey to the cross!

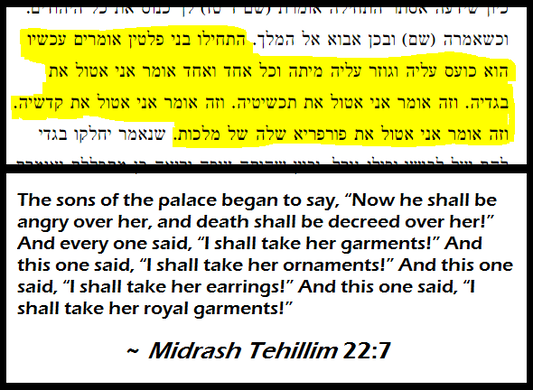

The fifth Messianic parallel of Esther is found in another midrashic text, that of Midrash Tehillim 22:7, where we read how the people reacted when they discovered she was going to appear uninvited before the king.

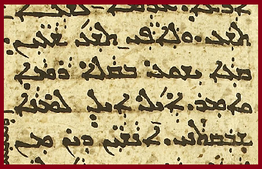

This aligns startlingly well with what happened to the clothing of Yeshua as He hung crucified upon the cross. We read of the incident in John 19:23.

Yet, the soldiers, when they had hung up Yeshua, they took His outer garments, and they made four parts – a part for each from the soldiers. Yet, His cloak was without a seam, from the top it was entirely woven.

The Gospel text tells us that the soldiers responsible for nailing Him to the cross stripped Him of His clothing, divided up what they could between them, and cast lots for the more expensive cloak. This shows essentially the same type of event taking place between what happened to Esther and what happened to Yeshua – garments were desired by those around them!

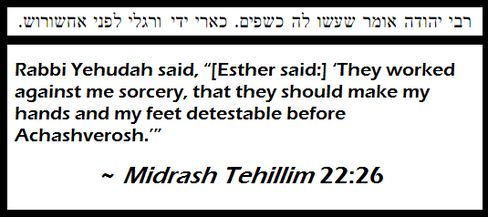

The sixth parallel is found again in the midrashic text of Midrash Tehillim 22:26. In that passage, we read an amazing statement about what Haman’s sons were said to have attempted to do to Esther.

This detail stands out starkly because of the fact that Yeshua had His own hands and feet nailed to the cross during His crucifixion. Although the actual accounts in the Gospels only tell us that He was crucified, we see that later, after His resurrection, His disciple Thomas mentions nails were used when he mentions his need to feel the wounds made during the crucifixion [see John 20:25]. Then we read in Colossians 2:14 that Yeshua personified the “bill of our debts” against the Holy One, and as such, was nailed to the cross. These details show us the intricate link between what it is said that Haman’s sons attempted to do against Esther in her Messianic role and what truly happened to Yeshua in His role.

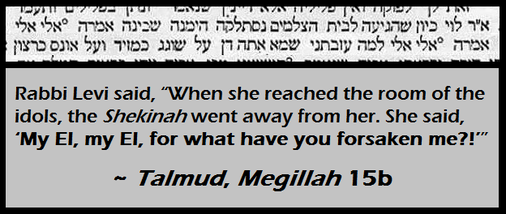

The seventh Messianic parallel found concerning Esther is mentioned in the Talmud, tractate Megillah 15b. It speaks to just how much it cost to be in a position where she had to lay down her life for the people.

We are told in this Talmudic text that the Shekinah (another designation for the Divine Presence of the Holy One) left her at the key moment she was about to enter into the throne-room. What a surprising piece of information the Jewish historic text gives us! This is viewed as entirely unexpected, to be sure, but the detail is so very important in the scheme of what we have seen and the Messianic context Esther is understood to have inhabited. When this happened, it is recorded that she cried out by quoting the words of King David that begin Psalm 22. In her most trying moment, we find that the Holy One put her in a position of unimaginable strain - she had to step forward without feeling the comfort and assurance of His holy Presence! This would serve to show her true character and willingness to lay down her life willingly for her people. Her Messianic nature is revealed powerfully in this detail.

This link to Yeshua could not be any clearer, for He is recorded as crying out the exact same words while He hung upon the cross, as we see in Matthew 27:46.

This link to Yeshua could not be any clearer, for He is recorded as crying out the exact same words while He hung upon the cross, as we see in Matthew 27:46.

And facing the ninth of the hours, Yeshua cried out with a loud voice, and said, “El! El! For what have You left Me?”

Here we see that Yeshua uttered the exact same phrase as Esther is said to have spoken centuries before in her similar anguish. This connection is notable in that He too experienced an abandonment of the Holy Spirit at that moment of His greatest need upon the cross. He felt the loss of connection, and had to remain willingly upon that torturous cross to show His dedication to the plan that would bring a redemption to the people.

Additionally, by understanding the ancient perspective of Esther having quoted the psalm, it becomes evident that Yeshua was likely referring to her plight in His quote, and not necessarily the unknown plight of David, who originally wrote those words. The context of Esther’s situation so perfectly aligns with His own, it can hardly be thought that Yeshua did not have her situation in mind when He cried out in the exact same manner.

Additionally, by understanding the ancient perspective of Esther having quoted the psalm, it becomes evident that Yeshua was likely referring to her plight in His quote, and not necessarily the unknown plight of David, who originally wrote those words. The context of Esther’s situation so perfectly aligns with His own, it can hardly be thought that Yeshua did not have her situation in mind when He cried out in the exact same manner.

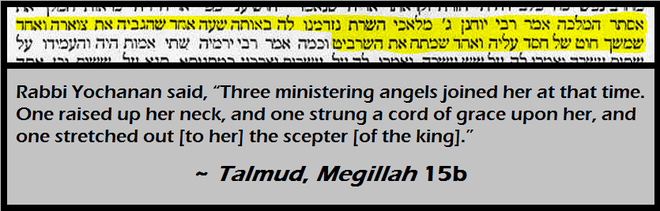

The eighth parallel can be seen by again returning to the Talmud, tractate Megillah 15b. It tells us what happened to Esther after she entered the throne-room and stood before King Ahasuerus in hopes for mercy for her people.

In that final moment when she needed it the most, Esther was given relief from the Holy One to accomplish her task. She was not rejected in her request, but was accepted before the king. She is said to have experienced a moment of divine favor which brought success to her trek before the pagan king. This aligns well with what happened to Yeshua in His final moments on the cross, recorded for us in Mark 15:37-38.

37 But Yeshua, He cried with a loud voice, and was delivered [over],

38 and the faces of the door of the Temple were ripped in two from the top until the bottom.

At His death, He is shown to have had final a burst of energy and strength, being able to cry out with a loud voice when His lungs would have already been drowning in fluid from the effects of positional asphyxiation. Yeshua cried out and then gave Himself up fully to death, and as a sign of acceptance for His righteous and selfless act being extended from the Holy One, the Temple’s first veil into the Holy Place was ripped in two! The connection of acceptance and unnatural grace is powerfully evident in Yeshua's and in Esther's situations.

All eight of these parallels show a Messianic figure who was willing to face ridicule, abuse, and a true spiritual horror in the effort to save others from a similar fate. Esther, like Yeshua who would come after her, exemplified the heart-breaking Messianic trait of ultimate self-sacrifice. Indeed, it must be remembered that the reason for the dramatic parallels between Esther and Yeshua only arose due to the command of Mordechai, whose own plight was horrific: Haman had decreed he should die upon the “gallows.” This detail really puts it all into perspective for us. The Hebrew book of Esther tells us repeatedly that Haman prepared an EYTZ upon which he planned to hang Mordechai. The term is translated in different ways depending on the English version used (“pole” being a popular alternative used), but the Hebrew word merely means “tree.” Curiously, in the New Covenant writings, we find that the word “tree” is used in five different passages to refer to the cross upon which Yeshua was hung for us (see: Acts 5:30, 10:39, 13:29; Galatians 3:13; 1st Peter 2:24). Could it be that the mechanism Haman intended for Mordechai was originally some form of the cross?

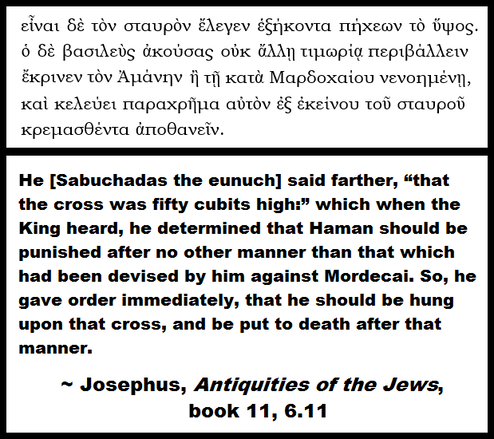

A definite answer might ultimately elude us, but based on what we know, it cannot be ignored that the ancient Jewish historian from the first century, Josephus, wrote this about what it was Haman erected for Mordechai’s demise, found recorded for us in his work, Antiquities of the Jews, book 11, chapter 6.11, where he references Esther 7:9.

A definite answer might ultimately elude us, but based on what we know, it cannot be ignored that the ancient Jewish historian from the first century, Josephus, wrote this about what it was Haman erected for Mordechai’s demise, found recorded for us in his work, Antiquities of the Jews, book 11, chapter 6.11, where he references Esther 7:9.

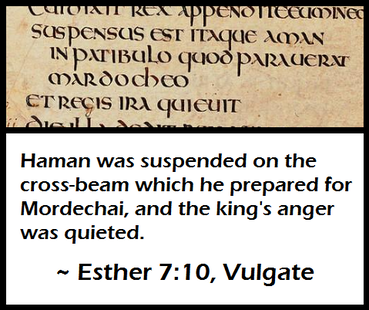

Josephus, who knew well the horrors of Roman crucifixion, and was also intimately-acquainted with the historical traditions of his own countrymen in Israel, felt that he was well-within contextual bounds to translate the Hebrew term EYTZ “tree” into the Greek STAURON “cross.” We find just a few centuries later that the Christian translator named Jerome likewise understood the Hebrew term as referencing the familiar Roman execution device as a cross, for in his Latin Vulgate translation of the book of Esther, he repeatedly utilized the words CRUX “cross” and PATIBULUM “cross-beam” to describe the EYTZ “tree” which Haman erected, and upon which he was ultimately hung. This example from 7:10 of the book shows the term for “cross-beam” blatantly used.

All of these details and parallels reveal that Esther was willing to lay down her life to prevent another from facing the consequences of this world of sin. Like Yeshua going to the death of the cross that He did not deserve, Esther acted to take upon herself the price of death so that Mordechai would never know the cross in such a vile way, and subsequently, all her countrymen would also be rescued from whatever other wicked forms of persecution awaited them in the minds of all who were spiritually akin to Haman’s hate. In a true sense, Esther faced the shadow of the cross that fell ominously upon her beloved Mordechai, and all her action was to see that shadow burnt away, even if it meant she would be consumed in the light of her revelation.

Esther, the unassuming daughter of Avichayil and the heedful wife of Mordechai, is thus seen at last to be a truly Messianic figure! Several individuals throughout Scripture are regularly appreciated for their own particular Messianic qualities, but we see that Esther, in all the details of the texts that are recorded about her willingness to do the unthinkable, so powerfully portrays the Messianic selflessness of laying down her life for her people!

Esther, the unassuming daughter of Avichayil and the heedful wife of Mordechai, is thus seen at last to be a truly Messianic figure! Several individuals throughout Scripture are regularly appreciated for their own particular Messianic qualities, but we see that Esther, in all the details of the texts that are recorded about her willingness to do the unthinkable, so powerfully portrays the Messianic selflessness of laying down her life for her people!

All study contents Copyright Jeremy Chance Springfield, except for graphics and images, which are Copyright their respective creators.