WORD MADE FLESH

by Jeremy Chance Springfield

7/3/2021

Unlike the three Gospels preceding it, John begins his account of the Messianic ministry of Yeshua with highly symbolic words that are full of meaning. The precise intent of his words has been a subject creating countless discussions and unique theological positions over the many long centuries since he first penned the enigmatic introduction.

Based on the terms John chose to use, the Christian Church elicited from them a complex doctrinal formation concerning the nature of the Messiah in relation to the Creator. While the reality of these utterances is something with which many are familiar, it is also important to admit that those particular theological perspectives so heralded by orthodox Christian belief were not the conclusions derived from the text by its original Jewish readers, for the positions arrived at that are now doctrines in the mainstream Christian faith were only codified several hundred years after the Gospel was penned at the infamous Council of Nicea. Phrases in John 1 such as “In the beginning was the Word,” and “the Word became flesh,” are bursts of spiritual significance that beg for a clearer explanation from Judaism than they have so often received.

Based on the terms John chose to use, the Christian Church elicited from them a complex doctrinal formation concerning the nature of the Messiah in relation to the Creator. While the reality of these utterances is something with which many are familiar, it is also important to admit that those particular theological perspectives so heralded by orthodox Christian belief were not the conclusions derived from the text by its original Jewish readers, for the positions arrived at that are now doctrines in the mainstream Christian faith were only codified several hundred years after the Gospel was penned at the infamous Council of Nicea. Phrases in John 1 such as “In the beginning was the Word,” and “the Word became flesh,” are bursts of spiritual significance that beg for a clearer explanation from Judaism than they have so often received.

Furthermore, the doctrinal conclusions reached at the council concerning the opening words of John’s Gospel were ratified by a distinctly Gentile group of believers. While there is nothing wrong with Gentiles attempting to understand the Messianic concepts of the Gospels, there was a huge problem at play in them in that they purposefully ignored and vilified any Jewish interpretation or contextual understanding of the Gospels.

This refusal to appreciate the accounts of the Jewish figure of Messiah in any Jewish framework robbed their perspective of the vital context needed to understand the assertions that open the Gospel of John in any way that would make sense to a Jewish mind. In retrospect, it should seem nothing less than madness to attempt understanding a spiritual text in a vacuum devoid of the background from which it arose. Such a rejection of the system of belief is unheard of outside of what happened to the persona of Yeshua at the hands of Gentile believers at Nicea.

For the undeniable truth of John's Gospel is this: A Jewish writer wrote of a Jewish persona using Jewish concepts for Jewish readers.

Rejection of anything Jewish thus strips the information in such a text from its true importance, and effectively disables the reader from ever properly understanding the original meaning of what was so carefully crafted for all believers to receive benefit. Unfortunately, that dismissal of and resistance to the Hebraic concepts embedded within the Gospel’s text has simultaneously stultified Gentile understanding of the words written therein while presenting an untenable Messianic candidate to Jewish minds who might otherwise be open to considering the legitimacy of the claims the text actually makes.

This refusal to appreciate the accounts of the Jewish figure of Messiah in any Jewish framework robbed their perspective of the vital context needed to understand the assertions that open the Gospel of John in any way that would make sense to a Jewish mind. In retrospect, it should seem nothing less than madness to attempt understanding a spiritual text in a vacuum devoid of the background from which it arose. Such a rejection of the system of belief is unheard of outside of what happened to the persona of Yeshua at the hands of Gentile believers at Nicea.

For the undeniable truth of John's Gospel is this: A Jewish writer wrote of a Jewish persona using Jewish concepts for Jewish readers.

Rejection of anything Jewish thus strips the information in such a text from its true importance, and effectively disables the reader from ever properly understanding the original meaning of what was so carefully crafted for all believers to receive benefit. Unfortunately, that dismissal of and resistance to the Hebraic concepts embedded within the Gospel’s text has simultaneously stultified Gentile understanding of the words written therein while presenting an untenable Messianic candidate to Jewish minds who might otherwise be open to considering the legitimacy of the claims the text actually makes.

It is this study’s intent to approach those words only in the framework of Judaism. I ask the reader to set aside any preconceived Christian notions about what the text means and be willing to entertain an ancient perspective of the matter that respects the Jewish viewpoint, and will hopefully provide a clearer portrait of what John was attempting to say to his fellow Jewish readers. What you will read herein is not a diminishing of the significance of the text but is rather intended to clarify the assertions in a Hebraic context that will allow us to better appreciate the Messianic role Yeshua plays in the Gospel of John.

In order to properly view the Messianic nature of the Gospel of John, it is important to return to the opening statement of his text and see why he chose the words he did to speak about the long-awaited fulfillment of the Messianic promise. John 1:1 is heavy with significance.

In order to properly view the Messianic nature of the Gospel of John, it is important to return to the opening statement of his text and see why he chose the words he did to speak about the long-awaited fulfillment of the Messianic promise. John 1:1 is heavy with significance.

In the beginning was the Word, and the Word itself was with Alaha, and Alaha was the Word itself.

I have translated this from the Aramaic text of the Eastern Peshitta version of John’s Gospel. It is essentially identical in meaning to the widely recognizable version translated from Greek texts:

In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God. (KJV)

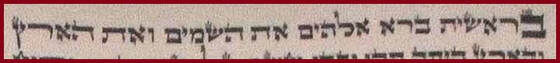

The opening statement, whether from Aramaic or Greek, conveys the same idea, but the wording of the Aramaic highlights an important factor slightly better: John is making a reference back to the very first verse of the Torah, in Genesis 1:1.

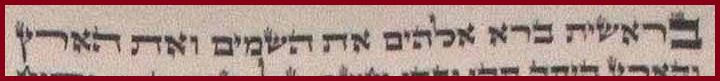

In [the] beginning, Elohim created the heavens and the earth.

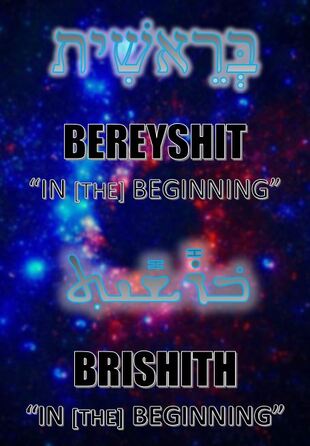

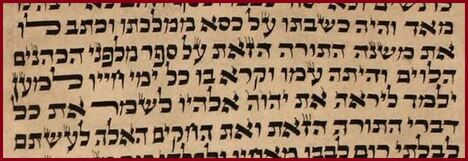

The first word of the Torah is the Hebrew BEREYSHIT—“in [the] beginning.” Similarly, the opening word of the Aramaic text of John 1:1 is BRISHITH, meaning the same thing, as it is merely the Aramaic cognate of the Hebrew term. This detail clearly shows that John was certainly intending a connection back to the first words of the Torah. Therefore, if we wish to correctly assess what he is asserting about Yeshua, it is important to understand what is going on in Genesis 1:1 that would legitimize his allusion to that passage.

To appreciate the connection and begin to see what John was doing, we need to address the factor that another Jewish text of spiritual significance chose to focus on Genesis 1:1, as well. The text of Tikkunei haZohar consists of 70 different explanations or commentaries on the term BEREYSHIT, and the words that follow it in Genesis 1:1. Over and over again in that text the reader is presented with the term BEREYSHIT, and then the text proceeds to explain it in novel ways to bring forth unique spiritual insights otherwise not readily apparent.

The text of Tikkunei haZohar is highly symbolic and endeavors to share important truths by using the first word of the Torah as a springboard to make relevant connections to the topics it presents. The Gospel of John is essentially doing the same thing as the Tikkunei haZohar—with the emphasis on the fulfillment of the Messianic promise to Israel. It uses the same formula to refer back to Genesis 1:1 as a springboard for introducing us to the one who fulfilled the role of the Messiah.

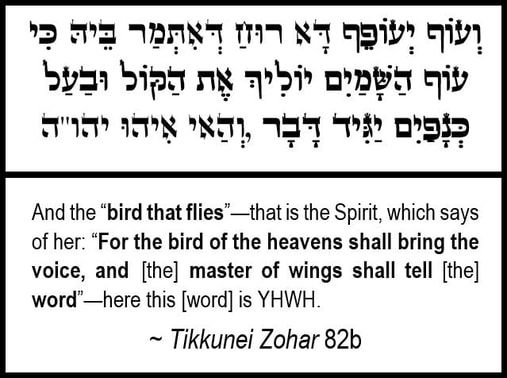

With that detail in mind, let us look at a brief quote from that text of Tikkunei haZohar and see how it can inform our attempt to understand what John was doing in his Gospel.

The text of Tikkunei haZohar is highly symbolic and endeavors to share important truths by using the first word of the Torah as a springboard to make relevant connections to the topics it presents. The Gospel of John is essentially doing the same thing as the Tikkunei haZohar—with the emphasis on the fulfillment of the Messianic promise to Israel. It uses the same formula to refer back to Genesis 1:1 as a springboard for introducing us to the one who fulfilled the role of the Messiah.

With that detail in mind, let us look at a brief quote from that text of Tikkunei haZohar and see how it can inform our attempt to understand what John was doing in his Gospel.

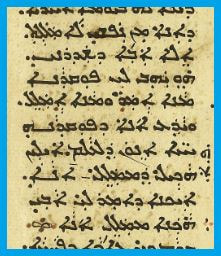

The text here quotes from Genesis 1:20 and Ecclesiastes 10:20 to make a connection to the creation event described in Genesis 1. The explanation of the verses is that the Spirit “bird” / “master of wings” does not “tell [a] word,” as in speaking a word, but that the Spirit “bird” actually “tells [the] Word,” as in speaking to the Word, which it then clarifies is the Creator! In this we thus see that the Creator Himself is referred to as “[the] Word!”

This detail shows that the ancient Hebrew concept of “the Word” was present, and that concept was directed firstly to the Holy One Himself.

This detail shows that the ancient Hebrew concept of “the Word” was present, and that concept was directed firstly to the Holy One Himself.

This alters the understanding of the “who” of the Word in John 1:1 from being the Messiah to instead being the Creator Himself. Now, it is obvious that John’s Gospel is about the Messiah, but this initial statement must be understood correctly in order for us to understand what is eventually stated explicitly about the Messiah, too.

Therefore, the ancient Jewish perception is that the Creator is the “Word” we see referenced here.

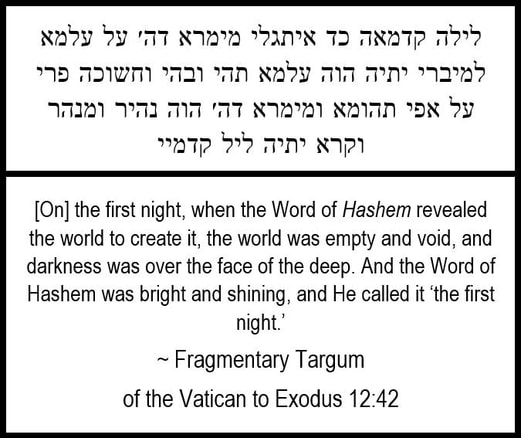

This notion of the Holy One as the “Word” can also be seen time and time again in the Aramaic translations of the Hebrew Scriptures, known as the Targums. In the following example, the context fits precisely what we see in John 1:1.

Therefore, the ancient Jewish perception is that the Creator is the “Word” we see referenced here.

This notion of the Holy One as the “Word” can also be seen time and time again in the Aramaic translations of the Hebrew Scriptures, known as the Targums. In the following example, the context fits precisely what we see in John 1:1.

The term used here to refer to the “Word” is the Aramaic MEMRA and is found hundreds of times throughout the Targums when speaking of the Holy One in action in this world. Understanding this factor helps us to place the notion of the “Word” of John 1 in proper context. It is the Holy One Himself in the framework of His expressive will / desire being accomplished. Just as when one speaks, the word coming forth from them is an expression of intent, desire, plan, thought, and so forth—but the word that comes forth from them is not literally “them,” although it represents them as close as possible.

That is the meaning of the “Word”: The Creator at work.

With these details concerning the Word, let us return to John 1:1 and see if this perspective aligns with what is written there.

In the beginning was the Word, and the Word itself was with Alaha, and Alaha was the Word itself.

Do John’s words fit in light of the Jewish usage of the “Word” as the expressive work of the Creator? In all honesty, that interpretation makes complete sense here! What this shows is that John 1:1 is not blatantly referring to the Messiah as the Word like orthodox Christian doctrine has so staunchly assumed. Rather, the text aligns in total harmony with the Jewish perspective of the Holy One as the “Word” who creates all things.

Such an understanding can be gleaned even by returning to Genesis 1:1 and viewing it in a slightly different manner than is usually taught.

Such an understanding can be gleaned even by returning to Genesis 1:1 and viewing it in a slightly different manner than is usually taught.

In [the] beginning, Elohim created the heavens and the earth.

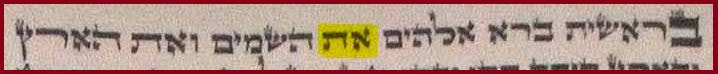

In this verse is a term that could potentially also be what John was referring to in the opening words to his Gospel. There is a Hebrew term here that is basically not translated into English. The Hebrew of the verse contains seven words. In the middle of those is the term EYT.

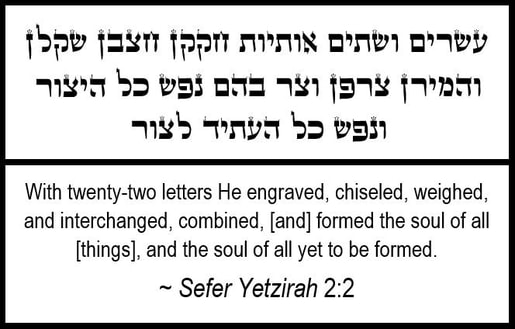

The term EYT fits the description of a “word” that was in the beginning with the Creator. Consisting of the first and the last letters of the Hebrew alphabet, it has several grammatical functions, depending on how it is used in the text, but the word EYT has the symbolic interpretation among the Talmudic rabbis as embodying the entirety of the Hebrew language, essentially as if saying in English “from A to Z.”

The ancient Jewish book of Sefer Yetzirah perceived this detail and tells us that the Creator used all twenty-two Hebrew letters to form creation, in that He spoke the worlds into existence through them.

Since creation came to be through the spoken word power of the Holy One, then the presence of the word EYT here when addressing the creation of the heavens and the earth is symbolically significant. We can understand this as the text telling us the Creator did all this through an expressive action. Such a perspective aligns with what we have already seen as the Creator and His “Word” carrying out His desire.

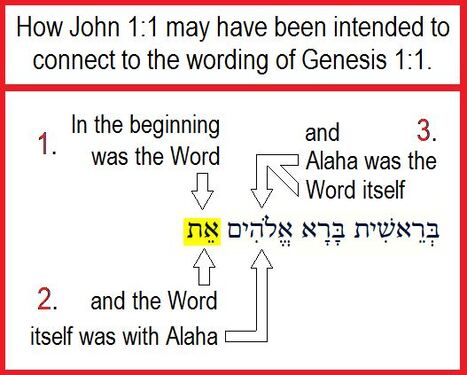

Notice in Genesis 1:1 above that the word EYT follows right after the title ELOHIM “Deity.” In this sense, the word EYT is “with” ELOHIM. The accompanying graphic shows this detail.

As the graphic attempts to explain John 1:1 in the context of Genesis 1:1, we see these conclusions:

1. “In the beginning was the Word” = the untranslatable Hebrew word EYT.

2. “And the Word itself was with Alaha” = the EYT linked to ELOHIM as the expressive power of His creative work.

3. “And Alaha was the Word itself” = we are really talking about the Source behind the Word—the Creator.

It is very interesting that Genesis 1:1 can be read and understood exactly according to the wording of John 1:1. There is a word signifying the expressive will of the Creator, and that word is with Elohim, but that word issues forth from Elohim, so in reality, Elohim is that word itself. This is admittedly quite different than traditional orthodox Christian interpretations of the intent behind John 1:1, but it is also important to acknowledge that this manner of viewing the Gospel’s opening statement aligns explicitly with Jewish viewpoints on the Creator and the creation event.

1. “In the beginning was the Word” = the untranslatable Hebrew word EYT.

2. “And the Word itself was with Alaha” = the EYT linked to ELOHIM as the expressive power of His creative work.

3. “And Alaha was the Word itself” = we are really talking about the Source behind the Word—the Creator.

It is very interesting that Genesis 1:1 can be read and understood exactly according to the wording of John 1:1. There is a word signifying the expressive will of the Creator, and that word is with Elohim, but that word issues forth from Elohim, so in reality, Elohim is that word itself. This is admittedly quite different than traditional orthodox Christian interpretations of the intent behind John 1:1, but it is also important to acknowledge that this manner of viewing the Gospel’s opening statement aligns explicitly with Jewish viewpoints on the Creator and the creation event.

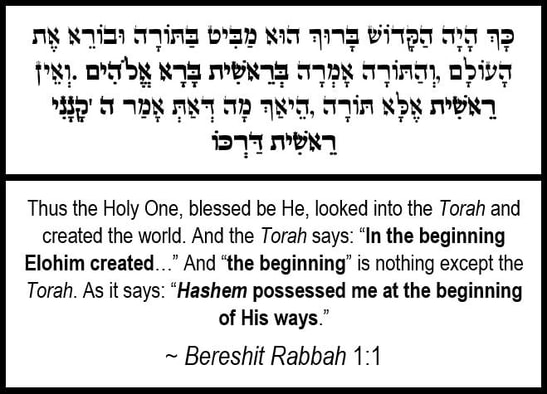

Based on this, we can also deduce from the presence of EYT in the Hebrew text of Genesis 1:1 that the Hebrew alphabet is the phonetic representation of the Torah itself, as the Torah is only made up of the twenty-two sounds of the Hebrew alphabet. This is important to note because other Jewish texts link the Torah to the creation event.

This text arrives at the conclusion that the Torah was present at creation based on the wording of Proverbs 8:22-31, part of which it quotes. That which “Hashem possessed” is referring to wisdom, and the Torah itself is referred to as “wisdom” in the first part of Deuteronomy 4:6.

And guard them, and perform them, for it is your wisdom and your understanding in the eyes of the peoples…

Now we can thus connect the “word” of John 1:1 to the untranslatable word of Genesis 1:1 – EYT, which is also, by necessity, the Torah.

So how does this connect to the Messiah? It all is a preface that eventually segues into the persona of the Messiah as the human expression of the Creator’s will.

This is seen blatantly in John 1:14.

So how does this connect to the Messiah? It all is a preface that eventually segues into the persona of the Messiah as the human expression of the Creator’s will.

This is seen blatantly in John 1:14.

And the Word became flesh and sheltered with us. And we saw his glory—the glory as that one and only who is from the Father, who is full of goodness and truth.

At this point now in John the phrase “the Word” is unequivocally referring to the Messiah and is no longer a reference to the Creator Himself.

A switch has occurred.

The Creator’s Word becoming flesh shows us that the Messiah is to be the vessel that conveys the will of the Holy One, just as the spoken word of the Creator carried out His will during the creation event. John is therefore making a spiritual parallel between the purpose of the Holy One’s Word and the purpose of the Holy One’s Messiah.

A switch has occurred.

The Creator’s Word becoming flesh shows us that the Messiah is to be the vessel that conveys the will of the Holy One, just as the spoken word of the Creator carried out His will during the creation event. John is therefore making a spiritual parallel between the purpose of the Holy One’s Word and the purpose of the Holy One’s Messiah.

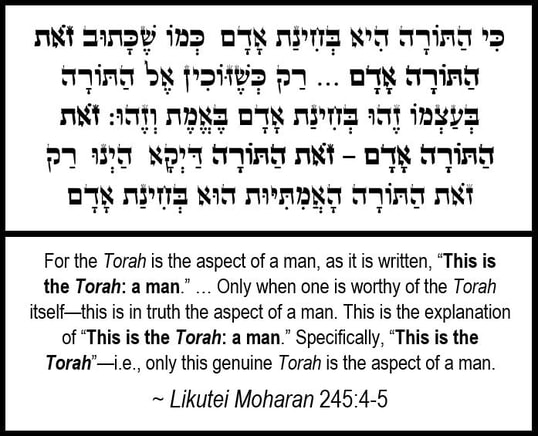

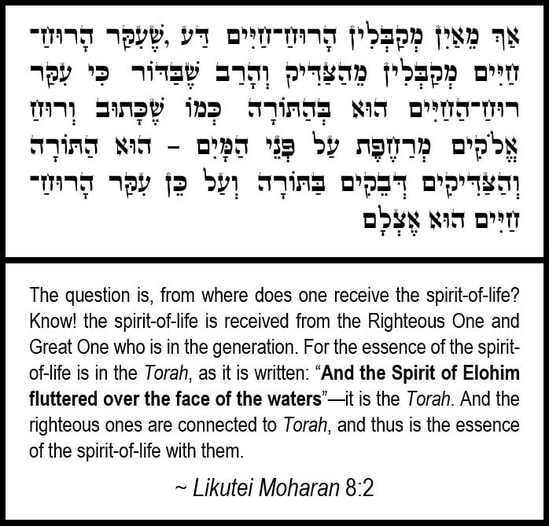

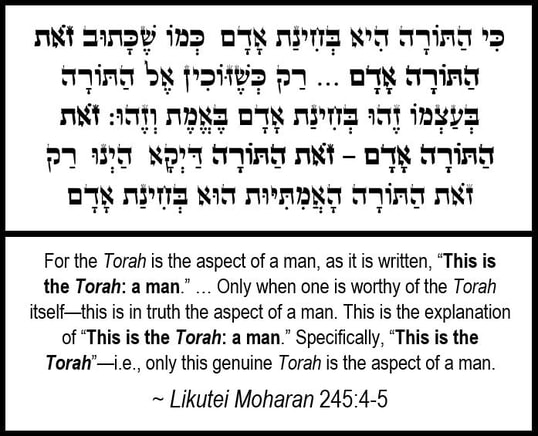

Turning to the Jewish text called Likutei Moharan, it can be seen how the Torah is thus embodied by the Messiah, as the text quotes from Numbers 19:14 but interprets it in a vastly different manner than is typically encountered:

We see here that a “true man” is called “the Torah.” That is, he is of such great merit that he is a vessel of divine authority.

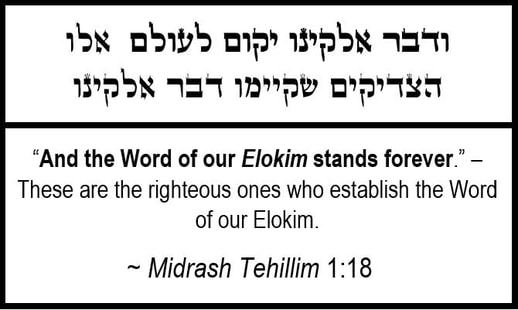

This concept is seen in another Jewish text called Midrash Tehillim.

This concept is seen in another Jewish text called Midrash Tehillim.

Quoting from Isaiah 40:8, the Midrash makes the astounding conclusion that these righteous ones are being called “The Word of our Elohim.” The Hebrew here is TZADDIKIM “righteous ones,” being the plural of TZADDIK—“righteous one.” In the Aramaic of the Peshitta, Yeshua is called several times ZADIKA, which is the Aramaic pronunciation of the same Hebrew word TZADDIK. He is thus understood to be the righteous one, and thus, by definition, is rightly called “the Word of Alaha.”

But how is the TZADDIK viewed to “stand forever?”

This idea stems from the concept of being linked to the Torah, as the following text explains.

This idea stems from the concept of being linked to the Torah, as the following text explains.

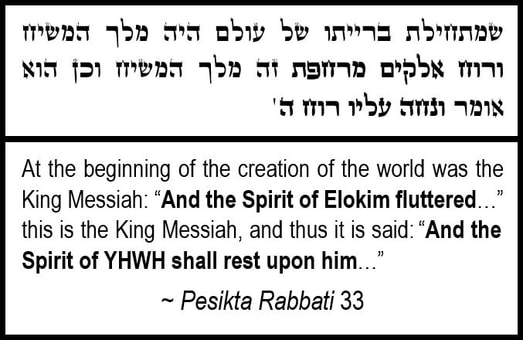

The passage quotes from Genesis 1:2 and shows us that the Spirit is connected from the Torah to the Messiah, which links Him to the Holy One in a special way. He is enabled to carry out the will of the Creator just as if He were the spoken voice of the Most High.

From this notion arises the following Jewish assertion:

From this notion arises the following Jewish assertion:

This passage clearly links the Torah-Spirit-Messiah into a cohesive thought, quoting from Genesis 1:2 but then adding in the connective Messianic idea from Isaiah 11:2 at the end. This shows the central importance of the role of the Messiah even from the outset of creation. The Spirit and the Torah make sense as being connected to the creation event, but what relevance does the Messiah have to that? Why is He included in that context?

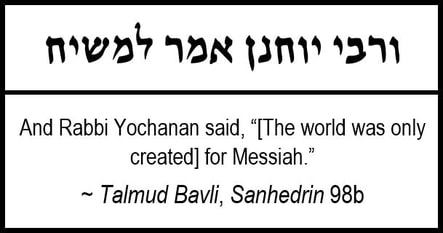

The answer can be found in a Talmudic discussion about for whom the world was even created. In that passage, two suggestions are presented, and then this third and final one is given that is shared below, and the text moves on to inquire about the Messiah’s name, seemingly settling the dispute over the reason for the world’s creation.

The answer can be found in a Talmudic discussion about for whom the world was even created. In that passage, two suggestions are presented, and then this third and final one is given that is shared below, and the text moves on to inquire about the Messiah’s name, seemingly settling the dispute over the reason for the world’s creation.

The world being created just for the Messiah is a sentiment highlighting the Messianic nature that fulfills all divine desires as requested, just like the Torah / Spirit / Word of the Creator at creation, for it is Messiah who embodies that Divine will and fulfills it in all His acts. He is the goal of all things because He is man at perfect harmony and spiritual alignment with the goal of the Holy One. In this, He embodies the Torah without question.

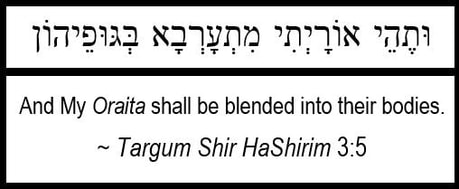

Calling someone the "Word" is thus entirely consistent with Jewish thought on the nature of a righteous person. The lines between man and divine will blur in such a one, to the point that spiritually-speaking, a transformation occurs in the merit of the individual who is living the Word, as this passage from the Targum declares.

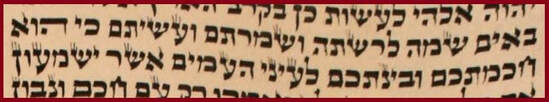

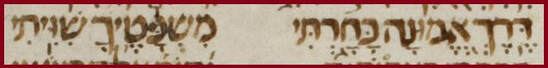

The above term ORAITA is the Aramaic cognate of the Hebrew TORAH, so it is the Torah that is blended into the body of the righteous. The idea that a man can embody the Torah in his flesh is one that is founded in the Torah itself. In Deuteronomy 17:18-19, directions are given to the king who shall sit as leader over Israel.

18 And it shall be when he sits upon [the] throne of his kingdom, then he shall write himself a copy of this Torah upon a scroll before the priests, the Levi’im.

19 And it shall be with him, and he shall read it all [the] days of his life, so that he should learn to revere YHWH his Deity, to keep all the words of this Torah, and these statutes, to perform them.

19 And it shall be with him, and he shall read it all [the] days of his life, so that he should learn to revere YHWH his Deity, to keep all the words of this Torah, and these statutes, to perform them.

While the passage as I have translated may not readily suggest a human is able to personify the Torah, when we investigate the way the Hebrew is written, the notion becomes apparent. First, we must appreciate that Hebrew terms are either masculine or feminine in how they are written, much like other modern languages, such as Spanish. However, since Hebrew is the vehicle through which the Creator conveyed His will to men, every grammatical aspect of the language is understood as holding a potential insight into eternal spiritual truths.

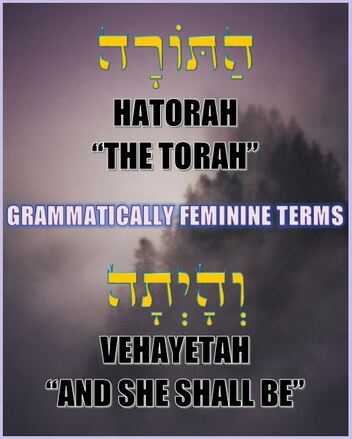

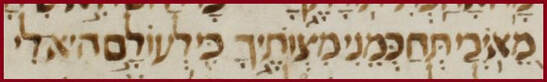

With that understanding, it must be appreciated that the term HATORAH “the Torah,” as found in verse 18, is grammatically feminine in Hebrew. It comes as no surprise, then, that the opening word of verse 19 in the Hebrew is likewise grammatically feminine: VEHAYETAH, which I have translated as “And it shall be”—referencing the Torah that the king is commanded to write. It could thus literally be rendered to reflect that fact: “And she [the Torah] shall be…”

With that understanding, it must be appreciated that the term HATORAH “the Torah,” as found in verse 18, is grammatically feminine in Hebrew. It comes as no surprise, then, that the opening word of verse 19 in the Hebrew is likewise grammatically feminine: VEHAYETAH, which I have translated as “And it shall be”—referencing the Torah that the king is commanded to write. It could thus literally be rendered to reflect that fact: “And she [the Torah] shall be…”

This feminine nature of the Torah is also seen explicitly in the Hebrew of Psalm 119:98.

By Your commandments You have made me wiser than my enemies, for it is mine forever.

The Hebrew literally reads KEE L’OLAM HEE LEE—“for she is mine forever.”

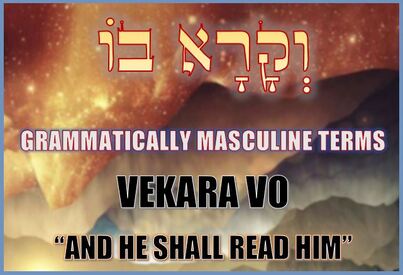

Returning to Deuteronomy 17 and the king who must write and learn from his Torah scroll, we see that the Hebrew text then presents an unexpected change in the grammatical structure when it says: VEKARA VO, which I have translated above as “and he shall read it,” but which could literally be rendered to emphasize the masculine grammar of the word VO, thus yielding something like: “and he shall read him.” The sudden change in gender is striking in the Hebrew text: the king is to write a copy of the Torah [feminine], and it [feminine] shall be with him, and he shall read it [masculine].

Returning to Deuteronomy 17 and the king who must write and learn from his Torah scroll, we see that the Hebrew text then presents an unexpected change in the grammatical structure when it says: VEKARA VO, which I have translated above as “and he shall read it,” but which could literally be rendered to emphasize the masculine grammar of the word VO, thus yielding something like: “and he shall read him.” The sudden change in gender is striking in the Hebrew text: the king is to write a copy of the Torah [feminine], and it [feminine] shall be with him, and he shall read it [masculine].

Since the text establishes clearly that the Torah is understood to be a feminine object, the change to a masculine term when the king reads it entails that the feminine Torah has become internalized in the masculine king—he has brought it into himself and is henceforth a Torah made flesh! Were it to remain outside of his being, it would continue to be referred to in the feminine, but since it becomes subsumed into his heart and mind, the change of expression occurs to signify that transformation: the king is to become a walking Torah scroll!

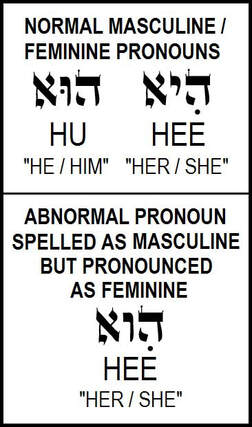

This feminine to masculine idea of the Torah is also hinted at in the text previously quoted from Deuteronomy 4:6, where we read that “it is your wisdom and your understanding in the eyes of the peoples…” The Hebrew term used there for “it” is the word HEE “she.” It is thus literally: “she is your wisdom and your understanding in the eyes of the peoples…” However, the way the term is spelled in the Hebrew points to the masculine, for it is spelled as if it were HU “he,” but it is pronounced as if it were spelled HEE “she.” The following graphic shows the distinctions.

The feminine Torah becomes masculine when it enters into a person to make them embody its eternal truths. In this way a person can become “a walking Torah,” a phrase commonly used in Judaism to speak of a person who is full of the Word. Such was the blatant assertion of the Rebbe Rayatz--Yosef Yitzchak Schneersohn, in his work, Sefer HaSichos.

Returning for a moment to the passage previously quoted above from Likutei Moharan 245:4-5, this concept of HEE “she” to HU “he” is presented in the Hebrew if we look carefully.

The initial statement of “For the Torah is the aspect of a man” literally is read as “For the Torah, she is the aspect of a man.” As the passage continues, however, and it explains only one who is worthy—who has strived to live it—is the Torah, do we then see the statement of “only this genuine Torah is the aspect of a man,” but which reads literally in the Hebrew as “only this genuine Torah--he is the aspect of a man.” When a man lives the Word he embodies it!

The idea is supported also in Psalm 119:30.

The idea is supported also in Psalm 119:30.

[The] way of trust I have chosen; Your judgments I set up.

The Hebrew term for “set up” is SHIVITI, which can also be read as “I resemble.”

It is the king—of all people—who is expected to embody the Torah. While the priests are viewed as having charge to teach the Torah to the people and expected to know it so as to properly instruct true worship at the Temple, it is the king alone whom the text of Scripture expects to internalize it and personify the Torah within his words and deeds.

It is the king—of all people—who is expected to embody the Torah. While the priests are viewed as having charge to teach the Torah to the people and expected to know it so as to properly instruct true worship at the Temple, it is the king alone whom the text of Scripture expects to internalize it and personify the Torah within his words and deeds.

Perceiving that the Scripture places the concept of being a living Torah in the framework of the nature of the king of Israel makes perfect sense when we see that John’s account shows so beautifully the Word made flesh is all about the Messiah—the one who shall reign as the king of Israel! The deeply symbolic and spiritual words as preserved in John 1 are meant to give honor and esteem to the one who fulfilled the Messianic hope by living and breathing the Torah in all His ways. Elsewhere, in John 12:49-50, Yeshua makes it clear that He is only presenting the will of the Creator to the people.

49 For I have not spoken of myself, but rather, the Father—He who sent me—He gave to me the commandment: what I shall say, and what I shall speak.

50 And [this] I know of His commandment: that they are life that is everlasting. These, therefore, that I speak—as my Father says to me—thus I speak.

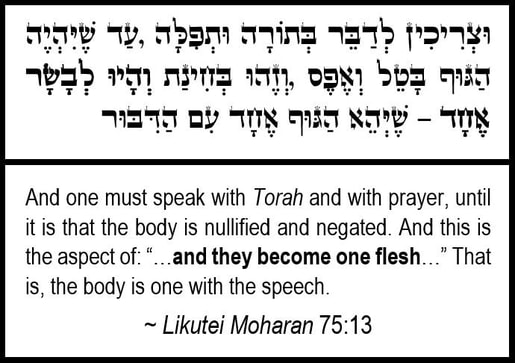

Yeshua is saying He has effectively negated His own will and the desires of His flesh in order to represent in full the will of the Holy One. This aspect of utter union with the Divine plan is mentioned as the goal for which we must strive in Likutei Moharan.

The text here tells us that if we will endeavor to affirm the truth and reality of the Torah and the Presence of the Creator with our mouths, that we will be able to bring even the body into submission, until there is no distinction between the Torah and ourselves.

That is the Word made flesh.

It is therefore important to make the effort to understand John’s words within the context of Judaism’s own assertions and connections, and not attempt to conflate the Messiah and the Creator into something never intended by the beloved disciple in the first place. Let us leave the edicts of Nicea to crumble to dust like the evanescing power of Rome when Constantine first ordered that unfortunate council. Let us instead seek and affirm the truths that Judaism has unwaveringly preserved that ultimately leads to the Scriptural Messiah in all His proper glory.

That is the Word made flesh.

It is therefore important to make the effort to understand John’s words within the context of Judaism’s own assertions and connections, and not attempt to conflate the Messiah and the Creator into something never intended by the beloved disciple in the first place. Let us leave the edicts of Nicea to crumble to dust like the evanescing power of Rome when Constantine first ordered that unfortunate council. Let us instead seek and affirm the truths that Judaism has unwaveringly preserved that ultimately leads to the Scriptural Messiah in all His proper glory.

Appreciating the words of John in their proper sentiment allows us all to hail Yeshua with the merit due Him and see in His obedience the worth He holds before the Holy One. In that way we can all agree with the avowal the Talmud so sagaciously made.

When we read the opening words of the Gospel of John, we can affirm that Yeshua, as the promised Messiah, truly personifies the desire of the Holy One as embodied in the scroll of the Torah—He is the Word made flesh!

All study contents Copyright Jeremy Chance Springfield, except for graphics and images, which are Copyright their respective creators.