TO FOLLOW A REBEL RABBI

by Jeremy Chance Springfield

1/15/20

The path Yeshua took that enacted a special flow of abounding mercy to begin spreading wildly into this world was not an easy trail to blaze. The lonely road to redemption was one burdened with opposition, rejection, and physical and spiritual challenge at seemingly every turn. This was not unexpected. Yeshua knew well the high cost of making the dream of the Most High come true; to restore the world to its intended place in the plan of eternity meant enduring personal ridicule, weathering religious persecution from all sides, and the possession of an unflinching willingness to set aside all the glowing accolades of men for a future “Well done” uttered by the Maker of man Himself. Yeshua had His work cut out for Him in every way. It would be a proving journey of self-sacrifice whose end would justify the means that asked everything of all who would follow Him on that lonely road to the Kingdom come at last.

During first-century Israel, this hope to see the dream of the Holy One realized on this earth was one shared by numerous Jewish people. Men of sincerity and zeal had taken up the reigns and attempted in their own ways to see it done. While several groups were key in this movement, the Pharisees were arguably the vanguard of this push to prepare the people to accept the reign of the Heavens upon the earth. With arduous fervor and the brazen insistence that all Jews were intended to be a nation of priest-level sanctity, they rode the wave of the spiritual reawakening that washed over Israel after the events of the Maccabean wars brought religious observance back into the forefront of Jewish life. Great centers of learning were formed, producing teachers and disciples of unusually erudite insight, applying even the Torah’s sometimes thinly described commandments in such a way that they seemed to reach into every facet of a person’s life. And yet, for all their passion and righteous endeavor, they ultimately fell prey to that trap always threatening to ensnare the heart of men: ego and institutionalism.

During first-century Israel, this hope to see the dream of the Holy One realized on this earth was one shared by numerous Jewish people. Men of sincerity and zeal had taken up the reigns and attempted in their own ways to see it done. While several groups were key in this movement, the Pharisees were arguably the vanguard of this push to prepare the people to accept the reign of the Heavens upon the earth. With arduous fervor and the brazen insistence that all Jews were intended to be a nation of priest-level sanctity, they rode the wave of the spiritual reawakening that washed over Israel after the events of the Maccabean wars brought religious observance back into the forefront of Jewish life. Great centers of learning were formed, producing teachers and disciples of unusually erudite insight, applying even the Torah’s sometimes thinly described commandments in such a way that they seemed to reach into every facet of a person’s life. And yet, for all their passion and righteous endeavor, they ultimately fell prey to that trap always threatening to ensnare the heart of men: ego and institutionalism.

It was in this framework of significant but unfortunately elitist religious devotion that Yeshua began His own maverick ministry. Eschewing the complex requirements of the multitude of teachers and religious schools of the day, and espousing instead an unheard of hybrid of accepted perspectives as well as brand new concepts via an appeal to authority from on High, Yeshua made it clear that He was not playing by the rules recognized by so many. To add insult to the perceived injury He was causing, the focus of His audiences was not the contemplative and engaging student body within the centers of learning established and revered by myriads – rather, He aimed his outreach to the am ha’eretz – the “people of the land,” those common folk of Israel typically unable to frequent synagogue and Temple, who were instead trying to just make it day to day in forging a living, and for whom most of the minutiae of rabbinic discussion concerned aspects of Torah the like of which they would never be faced. Such individuals were largely ignored and even often viewed with disdain by those involved in the several religious sects otherwise leading the way in spiritual matters. These acts of daring ministry set Him at odds in profound ways with those who otherwise should have been shoulder-to-shoulder with Him and His message of the necessity of true worship. He was at once recognized as a legitimate teacher and at the same time vilified for stepping so intentionally out of the bounds of the traditionally accepted methods of teaching.

When He wasn’t making waves as a rabbi who publicly underwent a baptism for repentance, or calming those waves through undeniably miraculous means, He proved to be a conundrum for those rabbinic sects that encountered His engaging teaching. Everyone was fair game – be it in a matter of teaching or a moment of correction – and His clever spiritual insights and in-depth hints at Scriptural matters coupled with a truly sincere care for those with whom He interacted sent representatives from all religious walks of life in Israel scrambling to cope with the unexpected momentous impact of His ministry. This unbridled and divisive nature eventually brought His entire persona into conflict with the status quo in a way that could not be denied. It was inevitable for all who would show sympathy towards Yeshua’s perspective to come under the ire of those in the religious schools who could not accept that His methods for outreach, albeit often spurning traditional tropes and frequently unprecedented in execution, were being so readily embraced. Therefore, to follow the rebel rabbi from Galilee meant a potential and very likely ostracization from the majority of the religious schools of the land.

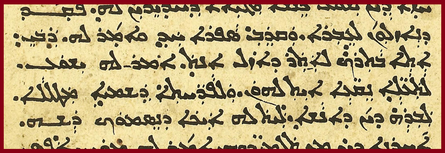

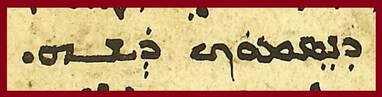

One account recorded in the Gospels illuminates this uneasy situation facing Yeshua and all who would come after Him. In a succinct expression, Messiah makes it clear that following in His footsteps would cost more than most are willing to consider. Unfortunately, however, the true intent of His words in this respect are unable to be realized and appreciated unless we view them as they are preserved for us in the ancient Aramaic text of the Eastern Peshitta text of Matthew. In that Gospel, we see a very brief but important encounter in chapter 8:19-20.

One account recorded in the Gospels illuminates this uneasy situation facing Yeshua and all who would come after Him. In a succinct expression, Messiah makes it clear that following in His footsteps would cost more than most are willing to consider. Unfortunately, however, the true intent of His words in this respect are unable to be realized and appreciated unless we view them as they are preserved for us in the ancient Aramaic text of the Eastern Peshitta text of Matthew. In that Gospel, we see a very brief but important encounter in chapter 8:19-20.

19 And one scribe drew near and said to Him, “Rabbi! I shall come after you to the country that you are going!”

20 Yeshua said to him, “Foxes have dens for them, and for birds of the heavens a tabernacle, yet for the Son of Man [there is] not for Him where He should recline His head.”

20 Yeshua said to him, “Foxes have dens for them, and for birds of the heavens a tabernacle, yet for the Son of Man [there is] not for Him where He should recline His head.”

The reader can see that the content as recorded in the Aramaic text, for the most part, agrees with the information commonly encountered in traditional translations stemming from the Greek manuscripts. However, when we dig just a little deeper into the actual Aramaic words of Yeshua, we will begin to see that the terms He chose were brimming with a rich depth that spoke volumes to the scribe to whom they were addressed.

In order to properly appreciate what Yeshua says in this passing encounter, the identity of the individual to whom He speaks must be highlighted. The scribe was a very different type of person than most of those who were following the Messiah. The majority of Yeshua’s immediate disciples were not men of great religious learning. Their typical difficulty understanding His parables and even some of His more direct teachings betrays this fact. A scribe, on the other hand, was an individual who lived and breathed the religious world and would have been more at home in the unique wordings Yeshua expressed.

In order to properly appreciate what Yeshua says in this passing encounter, the identity of the individual to whom He speaks must be highlighted. The scribe was a very different type of person than most of those who were following the Messiah. The majority of Yeshua’s immediate disciples were not men of great religious learning. Their typical difficulty understanding His parables and even some of His more direct teachings betrays this fact. A scribe, on the other hand, was an individual who lived and breathed the religious world and would have been more at home in the unique wordings Yeshua expressed.

Not only was the scribe tasked with accurately copying scrolls of Scripture for the next generation, or writing up marriage contracts or divorce papers as needed, he was more so immersed in an environment where the Word was discussed and debated – a backdrop where Hebrew and Aramaic were in constant and creative use. This setting put the scribe in a situation where he was overwhelmingly familiar with the nuanced usage of terms and the clever punning and parallels the rabbis were prone to employ. The subtleties of language were the scribe’s daily reality.

Yeshua knew precisely with whom He was dealing, and so His words, deceptively breviloquent to the untrained ear, spoke volumes to the scribe. Whereas the popular understanding of this passage is that Yeshua was merely telling the scribe He had no set home where the scribe would be able to retire at night, the actual import of what was being said is far more important and revealing than that. Yeshua already had a substantial number of followers – and a decent amount of those remained as constant companions who rarely left His side. To think that Yeshua’s reply to the scribe was intended to be taken in a straightforward and literal manner makes no sense with the situation surrounding the obviously itinerant rabbi. He could only have intended something else with the choice of words given.

In order to appreciate what Yeshua was telling the scribe, we have to examine His words alongside how those concepts were understood in ancient Judaism. Consider now His initial utterance:

Yeshua knew precisely with whom He was dealing, and so His words, deceptively breviloquent to the untrained ear, spoke volumes to the scribe. Whereas the popular understanding of this passage is that Yeshua was merely telling the scribe He had no set home where the scribe would be able to retire at night, the actual import of what was being said is far more important and revealing than that. Yeshua already had a substantial number of followers – and a decent amount of those remained as constant companions who rarely left His side. To think that Yeshua’s reply to the scribe was intended to be taken in a straightforward and literal manner makes no sense with the situation surrounding the obviously itinerant rabbi. He could only have intended something else with the choice of words given.

In order to appreciate what Yeshua was telling the scribe, we have to examine His words alongside how those concepts were understood in ancient Judaism. Consider now His initial utterance:

Foxes have dens for them

Foxes have dens for them

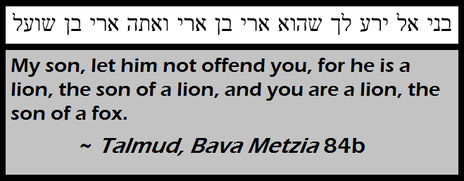

Yeshua is not telling the scribe the reality evident to anyone that a fox has a den. Rather, He is using cultural and religious language with which the scribe would have been immediately clued-in on. In the context of Jewish teaching concepts, when a fox is mentioned, it is a symbol for a teacher of the Hebrew Scriptures who is not considered the most erudite of scholars, or else is someone who believes themselves to be somebody important but has an over-inflated estimation of their true significance. Such usage can be seen in several scattered Talmudic references, each surrounding its own specific context, but every one of them referring to a fox as an inconsequential individual.

Once the statement of Yeshua is taken within the context of Jewish cultural usage, it can be seen to hint at something more than the lair of a fox. Yeshua is thus stating that for the newly established teachers of the Torah and Hebrew Scriptures in general, there is a place where they are welcome, and their authority recognized, even if they are not held in the highest esteem by teachers having the honor of many years behind them and numerous disciples to their name.

The second part of His statement is equally revealing when understood properly. He speaks of the “birds of the heavens” having a “tabernacle.”

The second part of His statement is equally revealing when understood properly. He speaks of the “birds of the heavens” having a “tabernacle.”

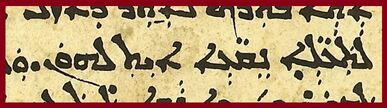

and for birds of the heavens a tabernacle

and for birds of the heavens a tabernacle

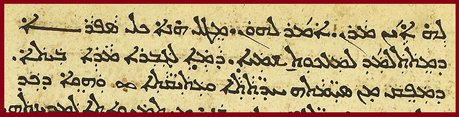

This part of Yeshua’s statement differs in my above translation the most from traditional translations rendered from Greek texts. While most English versions from Greek render the term as “nests,” the Greek actually uses a conjugation of the term SKENOS, literally meaning “tabernacle.” The Aramaic term used here also literally means “tabernacles,” being used elsewhere to refer to the Biblical festival of Sukkot “Tabernacles” (see my study: THE CENTURION’S SUKKAH).

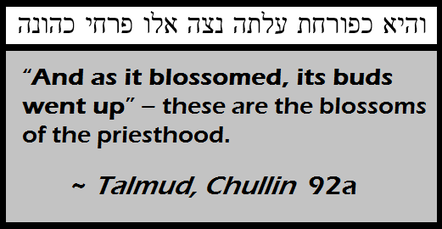

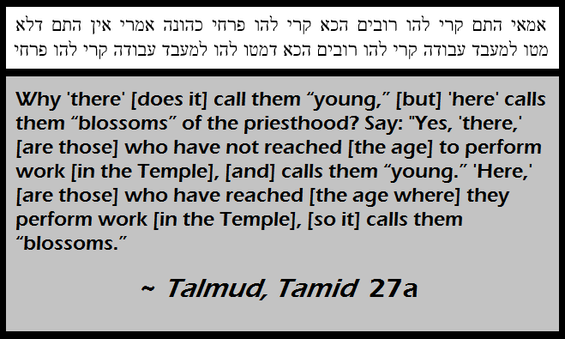

Under no literal circumstance does it mean “nest” like English translations have often rendered it – this choice of translation could only be derived from context clues when absolutely demanded. While it may seem like “nest” would be the right context, the hint here shows us something more is being intended. Aramaic also has another term altogether if such word were intended that literally conveys a bird’s nest: Q’NAN “to nest.” The fact that Yeshua used the word intended for a wooden SUKKAH / “tabernacle” in Aramaic was intentional on His part to alert the mind of the scribe for sure that He was not speaking of an avian subject, but rather, was speaking of “birds of heaven” in a completely different sense. Additionally, the word He used for “birds” points to a deeper intent, for the term PARAKHTHE “birds,” is a term whose cognate is shared with Hebrew, where it is there PRKH, which means “fowl” if pronounced as PERAKH, and “blossom” if pronounced as PRAKH. The significance of this is that the young men of the priesthood, those just starting out as functioning priests, were called by this very designation by the rabbis during the time of Yeshua, based off a unique interpretation of the content of a passage from Torah (see the below quote).

The young priests were therefore considered as “birds” or “blossoms” in the “Tabernacle” doing the work of heaven. This type of referent given them can be seen in the Mishnah, Middot 1:6, Mishnah, Sukkah 5:2-4, (see also its counterpart in the Talmud, Sukkah 51a), and Mishnah, Sanhedrin 9:6 (and its counterpart in the Talmud, Sanhedrin 81b). Yeshua is thus teaching also that for the established young priests, there is a place where they are welcomed, and their authority recognized (the “Tabernacle” / Temple).

These two concepts that Yeshua brings forth – foxes in dens and birds in the Tabernacle – are thus seen to have been a deeper reference to things the scribe would have readily understood: religious authorities of different background who were accepted in their respective settings. With the hints intended in this language properly appreciated from the Aramaic text, we are now able to address that final part of Yeshua’s response to the scribe in a way that will make absolute sense with what we have come to know about this matter.

He tells the scribe that while those subjects have an accepted environment, He does not.

He tells the scribe that while those subjects have an accepted environment, He does not.

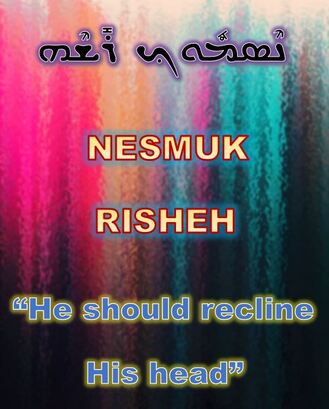

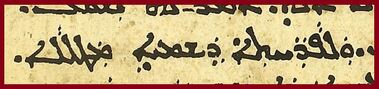

where He should recline His head

The difference between these lowly teachers and young priests, and the Messiah Yeshua, is that He says there is “not for [Him] where He should recline His head.” The Aramaic phrase for “He should recline His head” is NESMUK RISHEH.

The phrase is referring not just of a place to lay down, but more so, in context of the previous terminology and the hints made with them, to the important rabbinic act of ordination, known as SEMIKHAH, which literally means “lean on / be supported.”

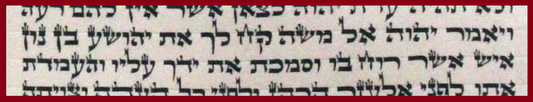

This concept of ordination is derived from the Torah itself, where we see that the Holy One commanded Moses to ordain Joshua as his successor in Numbers 27:18.

YHWH said to Mosheh, “You must take for yourself Yehoshua, son of Nun, a man in whom is the Spirit, and lean your hand upon him.”

This command to place his hand “upon him” is understood to have meant “upon his head,” derived from the similar wording of a transference using spiritual authority where the priest laid hands upon the head of the particular sacrifices (see: Leviticus 1:4; 3:2, 8, 13; 4:4, 24, 29, 33; 16:21).

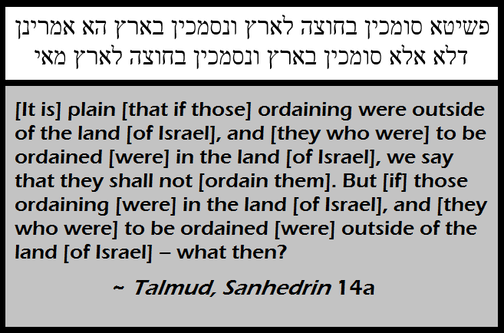

The Aramaic phrase of NESMUK RISHEH “to recline the head” that Yeshua uses refers to that very action of “to have a head leaned on” in the act of rabbinic ordination. We can see its direct cognate in the Talmud, Sanhedrin 14a, where rabbinic ordination is there referred to as NISMAKIN.

The Aramaic phrase of NESMUK RISHEH “to recline the head” that Yeshua uses refers to that very action of “to have a head leaned on” in the act of rabbinic ordination. We can see its direct cognate in the Talmud, Sanhedrin 14a, where rabbinic ordination is there referred to as NISMAKIN.

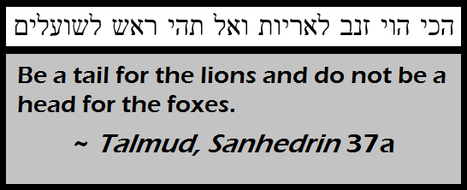

Such an act of recognized authority to teach by a specific school of Torah was done by the officiating rabbis literally leaning their hand upon the head of the newly ordained rabbi. The process of ordination in first century Israel was thus exactly what Yeshua was referring to by using the phrase that He did – stating there was “not for [Him] where He should ordain His head.” Literally, no place existed for Him that would ordain Him due to His novel positions and staunch adherence to solely teach what the Holy One told Him to share. Rather, His ordination could only have been from above – by the Holy One Himself, for he was apparently not educated in the rabbinic schools of the day (see: John 7:15, 9:29, 5:43; Matthew 21:23; Mark 6:2). Additionally, since he was unrecognized as an authority by others in authoritative positions, if he ordained a scribe who was following him, that scribe would not be accepted so readily by others.

This astoundingly concise response of Yeshua to the scribe, when rightly understood as a whole and in a very particular historical and religious context, is thus seen to be speaking of the lack of reception He was to receive by the recognized rabbinic authorities of the day. For a scribe to therefore follow Him would be for that individual to give up the acceptance of his skills and purpose from the rest of the religious community in Judaism. It would be career suicide, essentially, and Yeshua was using thinly veiled terminology that the scribe would have been immediately familiar with to let him know he needed to seriously count the cost of what following Yeshua as a scribe would entail.

This astoundingly concise response of Yeshua to the scribe, when rightly understood as a whole and in a very particular historical and religious context, is thus seen to be speaking of the lack of reception He was to receive by the recognized rabbinic authorities of the day. For a scribe to therefore follow Him would be for that individual to give up the acceptance of his skills and purpose from the rest of the religious community in Judaism. It would be career suicide, essentially, and Yeshua was using thinly veiled terminology that the scribe would have been immediately familiar with to let him know he needed to seriously count the cost of what following Yeshua as a scribe would entail.

Unlike most of Yeshua’s other followers, whose choice to adhere to the unconventional rabbi did not ostracize them from the ability to make a livelihood or be taken seriously as students of a spiritual teacher, a scribe educated in all that the scribal life involved would find it difficult to move forward in his familiar environment. However, though Yeshua sagely used a veiled reference to being “homeless” as a seeming future awaiting the scribe – should he follow Him, we read only a few chapters later that Yeshua makes a surprising reference to just such a scribe, and the decidedly not homeless situation of that man, as recorded in Matthew 13:52.

He said to them, “On account of this, every scribe who is taught of the Kingdom of heaven is likened to a fellow, a master of the house, who brought out from his treasures the new and the old.”

This blessed scribe, though likely rejected by his peers, is said to be a “master of the house.” Such a one who follows after Yeshua will find himself in spiritual possession of more than he was willing to let go of at the first. Although the choice to have Yeshua as his teacher would cause him to lose much in the circles wherein he was already quite comfortable, in the end, he could trust that more would be gained than ever was lost in the eyes of men.

This brief interaction of a well-meaning scribe with Yeshua displays the potential consequences for us all of taking a stand in a world where religious ideals, while originally sincere in intent, have become calcified by faith in a particular way, rather than faith in the One who makes the way for us at every turn. Yeshua’s unlikely ministry, flouting the boundaries of a cherished religious tradition, shows us in this simple but profound encounter that sometimes following the right path will have a true and legitimate price, but will one day find us gaining more than we could have ever imagined. To follow the rebel rabbi from Galilee comes at a cost, but the reward is eternally worth it!

This brief interaction of a well-meaning scribe with Yeshua displays the potential consequences for us all of taking a stand in a world where religious ideals, while originally sincere in intent, have become calcified by faith in a particular way, rather than faith in the One who makes the way for us at every turn. Yeshua’s unlikely ministry, flouting the boundaries of a cherished religious tradition, shows us in this simple but profound encounter that sometimes following the right path will have a true and legitimate price, but will one day find us gaining more than we could have ever imagined. To follow the rebel rabbi from Galilee comes at a cost, but the reward is eternally worth it!

All study contents Copyright Jeremy Chance Springfield, except for graphics and images, which are Copyright their respective creators.