THE SOURCE'S CODE

by Jeremy Chance Springfield

2/1/2024

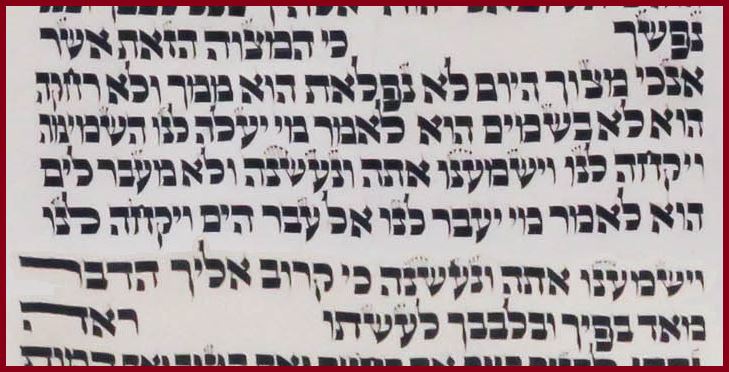

The Torah is unlike any other book in the world. Although filled with accounts recording events both ordinary and extraordinary, the content transcends what we can easily read with our physical eyes. The reality is this: reading the text with spiritual eyes gives us an experience surpassing the necessary limitations of the letter.

To read it only as one would any other book written by the mind of man will inevitably bring disaster—a spiritual corruption of the supernal content means deception and destruction are unavoidable. Spiritual truths must be approached in a spiritual way.

To read it only as one would any other book written by the mind of man will inevitably bring disaster—a spiritual corruption of the supernal content means deception and destruction are unavoidable. Spiritual truths must be approached in a spiritual way.

One could even say that the Source of all things concentrated the totality of His sublime truths into the spiritual code of the Word, and it is up to us to perceive behind the common text the luminous flow that is the language of the Spirit vivifying it and uniting it in harmony from beginning to end.

|

The text of the Torah, therefore, although written in mundane medium, is supramundane in nature. It exists as a liminal space, its letters and words the threshold of a nexus where heaven and earth meet, for in it the omniscient mind of the Spirit is expressed to the mortal mind of man. Because of this, our attempts to approach this frontier of infinity are easily hampered by the restraints we experience as physical beings in a realm where spiritual matters are constricted by our tendency to remain in the fleshly boundaries wherein lay all our comforts.

|

Paul articulated it best in Romans 7:14.

This is the reality we face. It is a sincere struggle to read the Word with eyes of faith, to perceive beyond the black of the ink the light of Heaven’s will. To assess the text of Scripture in the same manner as any other work written by the limitations of man’s mind is thus a travesty and a slighting of the potential eternal truths awaiting us in the insights that are embedded in each and every aspect of the Word.

The text exists in superposition—subsisting simultaneously in more than one form. To the casual viewer, it is an ancient Hebrew document preserved to this day with meaning for the faithful. To the faithful, however, it is worlds upon worlds of insight and application encoded for us to unveil and transform our lives in the light of His Presence.

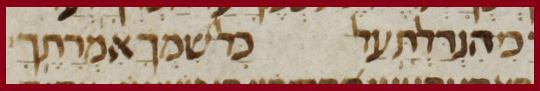

It was in this sense that King David uttered what he did in Psalm 119:18.

The text exists in superposition—subsisting simultaneously in more than one form. To the casual viewer, it is an ancient Hebrew document preserved to this day with meaning for the faithful. To the faithful, however, it is worlds upon worlds of insight and application encoded for us to unveil and transform our lives in the light of His Presence.

It was in this sense that King David uttered what he did in Psalm 119:18.

This statement authenticates the concept expressed concerning the unique nature of the Torah. The focus of Psalm 119 is on the Torah, with each line referring to the commandments in some endearing form or another. For the king to sing of a desire to see “wonders” in it is intriguing. The term “wonders” translates the Hebrew NIFLAOT that is in the text. This word can be rendered as “marvels,” or even “miraculous [things].”

Notice that King David demands that the Creator “must open my eyes” to see the wonders supposedly in the Torah. This detail means a normal reading of the Word is insufficient to glean deeper meanings and truths that must of necessity be fused into the very text itself.

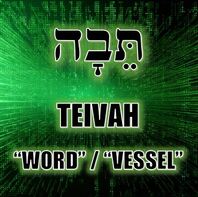

We can appreciate this notion by looking at the Hebrew terms that are used to speak of the “words” and “letters” which ultimately comprise the Torah. One of the Hebrew terms for “word” is TEIVAH. While it can certainly mean “word,” its literal definition is a generic “vessel” of some type in which to hold a thing.

We can appreciate this notion by looking at the Hebrew terms that are used to speak of the “words” and “letters” which ultimately comprise the Torah. One of the Hebrew terms for “word” is TEIVAH. While it can certainly mean “word,” its literal definition is a generic “vessel” of some type in which to hold a thing.

This term is used most famously to refer to what translators popularly render as the “ark” Noah built, as well as the “basket” in which the infant Moses was placed when he was put into the Nile river. These usages reinforce the “vessel” or “container” concept of the root word, but also serve to exemplify the root notion of TEIVAH as a “word.” A word is merely a recognized representation of a thought in the act of communication. Whether it be in vocalized form or written form, a word is a vessel carrying information from one mind to another.

Similarly, the Hebrew word for “letter”—the components which are combined to form a word—is the unassuming term OT (pronounced identically to the English “oat”).

Similarly, the Hebrew word for “letter”—the components which are combined to form a word—is the unassuming term OT (pronounced identically to the English “oat”).

This simple term for “letter” is significant, for it also has the concept of “to join / “to fit together.” Such a meaning makes sense in the fact that letters must be “joined” one to the next to form words. In its altered pronunciation of ATHA it also means “to bring” a thing from one place to another. What we have in the concept of OT “letter,” then, is the idea of a channel or flow from one thing to another to yield a whole made up of its necessary parts. It is a flow of divine coding that relays a higher truth to our lowest of realms. The letters of Torah are, to use a concept from physics, the quantum structure of all spiritual truth.

With this understanding we can appreciate afresh the words of Yeshua in Matthew 5:18.

With this understanding we can appreciate afresh the words of Yeshua in Matthew 5:18.

This is incredible when considered: the term “yudh” here is merely the Aramaic pronunciation for the Hebrew letter Yud. It is the smallest by far of all the letters, and in many instances it can be removed from its position inside a term without altering the definition or pronunciation. Countless examples of this happening appear throughout the Hebrew text of Scripture. For Yeshua to thus assert that not even one such letter can be removed from the Torah is His way to emphasize the vital centrality of the entire Torah and the value inherent in every quanta of information that comprises the whole. This is saying that there is a purpose in the letters beyond what is even translatable.

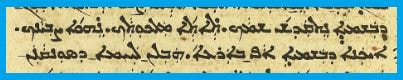

Such an idea is hinted at with the mention of a “yudh,” but is outright stated in Yeshua’s next mention of a “stroke” not passing away from the Torah. Precisely what He meant by this term is questionable. The term He used was SERTA in the Aramaic language, and in its generic sense, it merely means a “line” of some unspecified type.

Such an idea is hinted at with the mention of a “yudh,” but is outright stated in Yeshua’s next mention of a “stroke” not passing away from the Torah. Precisely what He meant by this term is questionable. The term He used was SERTA in the Aramaic language, and in its generic sense, it merely means a “line” of some unspecified type.

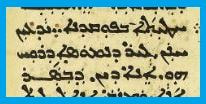

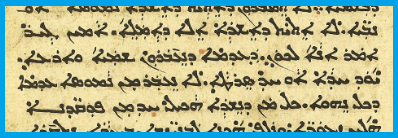

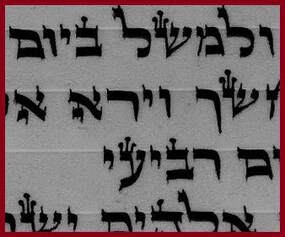

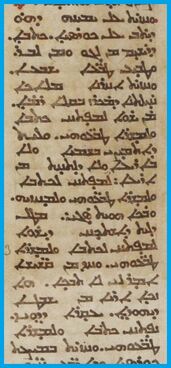

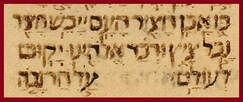

It may refer to SIRTUTIN—the scored lines marked by a thorn across the parchment of a Torah scroll which help maintain an orderly flow, and from which hang the Hebrew words the scribe writes in ink. Alternatively, it may mean merely the minuscule upwards flourish of ink (called a KOTZ “thorn” in Hebrew) atop some Hebrew letters, or else might refer to the ornate ink strokes that also are affixed to many of the Hebrew letters (called TAGIN “crowns” in Aramaic).

In the following image from a Torah scroll, one can see the SIRTUTIN as the brighter, uninterrupted horizontal lines upon which hang the letters. One can also see the upwards flourish—the KOTZ “thorn”—by which the letter itself actually hangs upon the SERTA. Additionally, on several letters one can see the ornate TAGIN that are more pronounced than the smaller KOTZ. All of these are technically defined as a SERTA “line,” and all could potentially or actually serve as the SERTA Yeshua claims to be invaluable as part of the divine information of the text—effectively existing as a superposition feature of the Torah.

When we view this from the perspective of quantum mechanics, there is a striking parallel that arises. Any system of information exists in a particular state. That information is viewed as a wave function, wherein the individual information occurs in a deterministic state of probabilities, existing simultaneously in an either / or / and type fashion. However, when the information is observed or measured, it collapses from a probability to a defined place in the field of information.

In this sense, the SERTA serves as a wave function, where all probabilities of content could potentially exist, but when a quanta of information is observed upon the SERTA--the quanta being a Hebrew letter which is linked straight to the SERTA via its own "SERTA" of a KOTZ or TAG / TAGIN--only then does the probable wave function collapse into a defined field of information. Hence, it exists in a manifold state of superposition.

In this sense, the SERTA serves as a wave function, where all probabilities of content could potentially exist, but when a quanta of information is observed upon the SERTA--the quanta being a Hebrew letter which is linked straight to the SERTA via its own "SERTA" of a KOTZ or TAG / TAGIN--only then does the probable wave function collapse into a defined field of information. Hence, it exists in a manifold state of superposition.

Despite the subtle question as to Yeshua’s precise intention of the term, He is clearly referring to marks that are in addition to the actual letters which comprise the text itself. The SERTA features on the letters could easily be removed without creating a question as to the identity of the letters. This would seem like those lines are therefore superfluous, but Yeshua's words assert the opposite: they are absolutely necessary. This shows that everything in the Word is imbued with meaning beyond normal perception: a superposition of being that allows the intent of the Torah to relay and accomplish all that is required for reality.

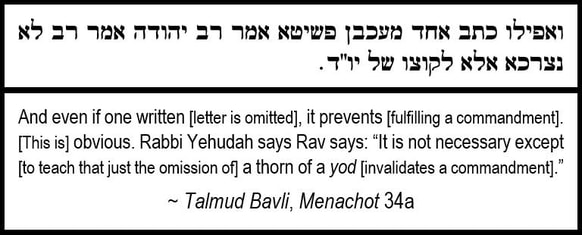

Interestingly, the Talmud Bavli, Menachot 34a, includes a unique remark about the necessity of a command of the Torah being performed only when its entire stated concept is preserved in the text.

Interestingly, the Talmud Bavli, Menachot 34a, includes a unique remark about the necessity of a command of the Torah being performed only when its entire stated concept is preserved in the text.

This assertion is essentially identical to that made by Yeshua in Matthew 5:18. It clearly pairs the letter Yud and the stroke of the KOTZ to underscore its argument of the vital preservation of every part of the written Torah.

The reason each and every letter of the Word is necessary—even when the term in question may not be affected in pronunciation or definition if a letter is omitted—has to do with the supernal nature of the Torah. Although it has been entrusted to believers for safekeeping and performance, its true origin is beyond the physical realm, like a coding language residing without corruption in the heavenly worlds. Corruption means the code would no longer function, and the Creator will not let that happen.

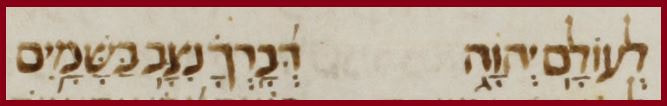

This is hinted at in the text of Psalm 119:89.

The reason each and every letter of the Word is necessary—even when the term in question may not be affected in pronunciation or definition if a letter is omitted—has to do with the supernal nature of the Torah. Although it has been entrusted to believers for safekeeping and performance, its true origin is beyond the physical realm, like a coding language residing without corruption in the heavenly worlds. Corruption means the code would no longer function, and the Creator will not let that happen.

This is hinted at in the text of Psalm 119:89.

This fact reiterates the notion that the Torah exists in a superposition, or what modern science might label as being trans-dimensional—its nature crossing the boundaries of heavenly and earthly realms. In such a way it acts as an interface with the highest worlds, and so our performance of it encompasses not only what it bears upon in this world, but also the facets of it that exist in those higher dominions.

It is important to clarify this truth in light of the assertions made by Moses in Deuteronomy 30:11-14.

13 And neither is it beyond the sea, for you to say, ‘Who shall cross for us over the sea, and shall bring it to us, and we shall hear it, and perform it?’

14 For near unto you is the Word—very much so! In your mouth, and in your heart—for you to perform it!

14 For near unto you is the Word—very much so! In your mouth, and in your heart—for you to perform it!

The context here is that the Torah is not beyond our ability to perform—not that it is not also existing in a heavenly realm. The text even uses the same term that King David used in Psalm 119:18—NIFLAOT “wondrous.” Here, it says it is not NIFLAOT, yet King David later requested to see NIFLAOT from the Torah. Hence, the context is markedly different. All it is conveying here is its accessibility for believers, not its transcendent nature.

Yeshua taught that the will of the Most High, as expressed in His Torah, must be drawn down into this world, as we see recorded in Matthew 6:10.

Yeshua taught that the will of the Most High, as expressed in His Torah, must be drawn down into this world, as we see recorded in Matthew 6:10.

The Creator’s will is performed in the heavenly worlds without question. It is here in this fallen place that we must strive and pray that we connect with what is above, bringing the harmony of His plan into all parts of creation. While it can be a seemingly daunting task set before us, knowing that His Torah is performed in the heavens means we can unify it here on the earth with our determined efforts to align with Him.

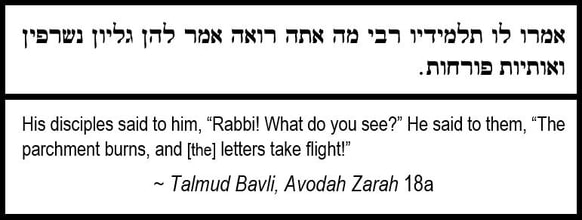

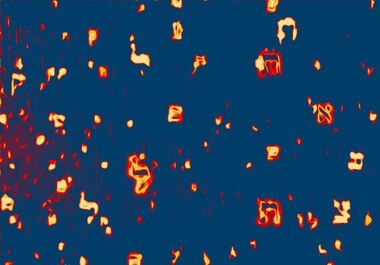

Such a special characteristic of the Torah is captured solemnly in an account from the Talmud Bavli, Avodah Zarah 18a, where it presents the martyrdom of Rabbi Chanina ben Teradyon at the sadistic hands of the Romans. They wrapped him in the Torah scroll he had been flagrantly studying from despite the decree against it, and then lit it afire so that he would burn to his death. As the flames consumed him, we read of the question posed to him and his incredible answer.

In this moving record of the martyrdom of one who refused to hide his allegiance to the Word, we see the incredible depiction of the heavenly essence of the Hebrew letters that comprise a Torah scroll. In his final moments he beheld the holy letters ascending unburnt while all else was consumed in the flames. The claim that he saw them ascending is to suggest they were returning to a higher plane of existence.

The notion that the letters of Torah exist beyond the limitations of created things, being basically indestructible in their spiritual makeup, is not foreign to Scripture.

Consider the words of Psalm 138:2 in this context.

Consider the words of Psalm 138:2 in this context.

Exactly what is meant by this declaration has been debated, but we should consider this reality: the pronunciation of His personal name has not been allotted for the masses to honor or abuse—it is, for all intents, obscured. His Word, however, has been preserved with ancient witnesses to corroborate its content. He has preserved and magnified His Word of truth in comparison to His name.

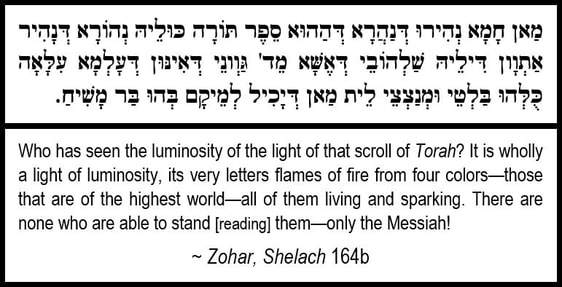

This idea of the Torah being exalted in the supernal realms is also discussed in an interesting passage in the Zohar, Shelach 164b.

This idea of the Torah being exalted in the supernal realms is also discussed in an interesting passage in the Zohar, Shelach 164b.

This amazing depiction of what is occurring in the heavenly worlds concerning a fiery and living supernal Torah that can only be read by the Messiah is nearly identical to the vision given to John in Revelation 5:1-5.

|

1 And I saw upon the right of He who sat upon the throne a book that was inscribed from inside and outside and sealed [by] seven seals.

2 And I saw another mighty angel, who proclaimed in a loud voice: “Who merits to open the book and to loosen its seals?” 3 And none were able in the heavens, and none in the earth, and none under the earth, to open the book and to loosen its seals and gaze at it. 4 And I wept very much, on account that none were found who merited to open the book and to loosen its seals. 5 And one from the elders said to me, “Do not weep! See! the Lion is victorious from the tribe of Yihuda! The Root of Dawid—he shall open the book and loosen its seals!” |

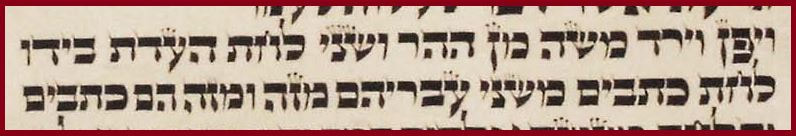

Notice in this vision that the text seen is not identified, but the details that are included are sufficient to recognize what is being referenced: it is written on both of its sides. This detail closely aligns with one that is recorded in the book of Exodus 32:15.

The tablets of the Torah Moses brought down from Mount Sinai were inscribed on both sides—a detail not typically depicted in artistic representations of the event, and so it is one that is easy to miss when we consider how they looked in our imagination.

Elsewhere, in Devarim Rabbah 1:1, we read an explanation about the detail of a text being written on both sides.

From these clarifications we find that the New Testament depicted a carefully preserved and safeguarded heavenly Torah that only Messiah is able to utilize.

But why? Why guard the Torah above all else?

That is because it conveys who our Creator truly is—beyond the mere pronunciation of His name. We find the answer more fully in Hebrews 4:12.

But why? Why guard the Torah above all else?

That is because it conveys who our Creator truly is—beyond the mere pronunciation of His name. We find the answer more fully in Hebrews 4:12.

Just as we read in the passage from the Zohar above, we see the New Testament claiming outright that the Torah is alive.

It has an active purpose that directly affects mankind—from the physical to the spiritual. Therefore, it must transcend the physical and exist simultaneously in the supernal realms in a special way. The text of Tanya, Part II, Shaar HaYichud VehaEmunah 11:7, presents an incredible notion that develops on what the author of Hebrews 4:12 was asserting.

It has an active purpose that directly affects mankind—from the physical to the spiritual. Therefore, it must transcend the physical and exist simultaneously in the supernal realms in a special way. The text of Tanya, Part II, Shaar HaYichud VehaEmunah 11:7, presents an incredible notion that develops on what the author of Hebrews 4:12 was asserting.

Here we read that the letters of the Torah in its supramundane aspect are representatives of the very nature and attributes of the Holy One Himself! This is why each and every word and letter must be preserved perfectly—it is an aspect of the Source itself, a part of the whole that conveys who He is to His creation. Looking at His Word from this perspective means that when we are obedient and perform the commandments we are actively engaging with His very nature! To merely be satisfied with the surface level aspects of His Torah is to miss the deeper ways in which we can connect with our Maker’s own attributes. Believers should undeterredly pursue what it means to link to the Source Himself, and not just to read the “code” of the written Word. We must recognize that every time we encounter the text we are standing on the cusp of forever, rending the veil of this physical world and peering into the vast unending reality that is the Holy One’s own nature.

The purpose of the Torah is to transform us into His image—into those who are prepared in every way to eventually assume the eternal roles we are meant to take on as His people. While confined to this physical life until death, believers at the resurrection will at last utilize the spiritual work of His Word in its fullest expression. Every interaction in faith with it here and now, every alignment we make in obedience to His will, equips us from the physical to the spiritual to be who we are intended to be for His purposes.

The text of 1st Peter 1:22-23 speaks of this purpose of interacting with His living Word.

|

22 Your souls shall be consecrated by hearing of the truth, and shall be full of love that is without receiving of faces, that from a heart cleansed and matured you shall love each other, 23 as a man who is born anew—not from the seed that wears out, but from that which does not wear out—by the living Word of the Deity that abides for eternity. |

The believer must be transformed by our interaction with His Torah—His attributes. We cannot be content to obey in the mechanical performance of a shallow compliance, for His eternal nature awaits us in the Word that is living and reactionary with who we are in our journey. A dedication to seeking after His expressive reality in all its many depths is what being His people is all about. The light of His Word is here to reveal Him, and we must not miss the greater rewards that come with seeing wonders from His Word.

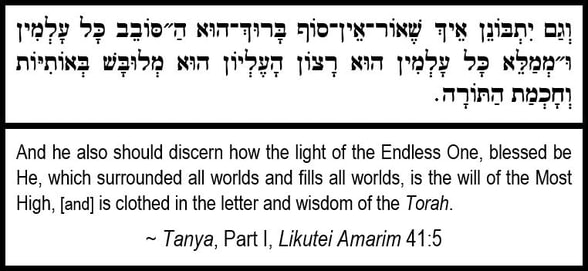

The text of Tanya, Part I, Likutei Amarim 41:5 addresses this need to discern more than what exists on the surface of His Word.

This revelation of the Most High is infused into every facet of the text—a supernal truth resonating within each and every word and letter of His Torah. The text is a glimpse into the eternal realms of the Spirit. It is nothing like the words of man and the books that are written, lauded, then forgotten.

It is as everlasting as its Author.

This reality is expressed in Isaiah 40:8 in a beautiful way.

It is as everlasting as its Author.

This reality is expressed in Isaiah 40:8 in a beautiful way.

In this truth we can trust that the opportunity given to us to seek out the Source for existence is one that will be beneficial beyond our dreams. All reality is based on the perpetuity of His Word. It is as rich and eternal as the Spirit who gave it. If we are willing to make the effort to engage it with spiritual eyes, to not be satisfied with reading it as we would any secular work of man, then surpassing wonders surely await that will draw us closer to understanding the Creator's nature and help us to love the things He loves. While all else passes, the Torah remains without corruption, the Source’s code operating flawlessly throughout all the myriad facets of creation to bring all things back into the proper context of His perfect will.

All study contents Copyright Jeremy Chance Springfield, except for graphics and images, which are Copyright their respective creators.