Purim in the Torah

by Jeremy Chance Springfield

The festival of Purim (Persian for “Lots”/ “Lotteries”) is filled with irony and intrigue, serving as the envelope for the secret presence of the Most High in the affairs of His people, showing Himself working for good even in the worst scenarios. The underlying principle at work is of His sovereignty over all things – every situation is under His control. You won’t find anything “surprising” the Holy One. Even random events to us are all part of His incomprehensibly-beautiful orchestrated masterpiece of redemption.

This festival above all others really points to the “Kingship” of our Creator over all things. It is all about Malchut – His reign over existence. In fact, there are one-hundred and sixty-seven (167) verses in the book of Esther, from which the festival of Purim is mandated, and there are over two-hundred and fifty (250+) instances of the root word for “King / Kingdom / Queen” in those verses! This portrays the underlying theme of HIS sovereignty over every facet of life. He is the King, His is the Kingdom, and we all are His subjects – whether we are aware of this reality or not!

OUTSIDE BUT WITHIN

This day is uniquely special because it is the only festival that is accepted as Scriptural yet not contained in the Divinely-ordained festival list of the Torah. Unlike Chanukah, which appears in the historical / apocryphal book of Maccabees, and thus is not considered inspired by all who worship the Holy One of Israel, Purim is actually accepted by the Hebrew people as well as Gentile believers in Messiah as a festival found in Holy Writ. Because of this, it holds a special place amongst the festivals due to it being “outside” of the Torah itself.

This day is uniquely special because it is the only festival that is accepted as Scriptural yet not contained in the Divinely-ordained festival list of the Torah. Unlike Chanukah, which appears in the historical / apocryphal book of Maccabees, and thus is not considered inspired by all who worship the Holy One of Israel, Purim is actually accepted by the Hebrew people as well as Gentile believers in Messiah as a festival found in Holy Writ. Because of this, it holds a special place amongst the festivals due to it being “outside” of the Torah itself.

However, just because it is not commanded to be done in the Torah –since it is the commemoration of an event that had yet to even occur when the Torah was finalized– does not mean that its eventual existence and significance are not hinted at within the Torah itself. That may sound strange at first to consider, but so much of the Word is prophetic in so many facets – even passages that do not seem to be thus on the surface can have undertones of future application. Given this reality of the multi-faceted surface of the Word, if we look closely at certain passages of Torah, we can see that Purim is indeed hinted at there in truly amazing ways.

To a very powerful degree, the scroll of Esther is actually imbued with an end-time prophetic nature that could be well-said to surpass that of the other prophetic books. Indeed, it is in many ways kin to The Song of Songs on a mystical level, and as such parallels the New Testament book of The Revelation, but in the Tanakh. The very title of the book in Hebrew is Megillat Esther – which translates if read in a certain way into “The Hidden Revelation.” It speaks to the physical rescue from evil for Yah’s people, which in reality leads to the ultimate and final rescue from all evil for creation. The book can be mined profusely to yield these amazing end-time symbols and details, but yet that is not the subject of this particular study. It is sufficient to say that the book is of immense value beyond just a frivolous day of feasting by which men approach it so often today.

The focus for this study is the amazing reality of this strange festival as it is found hidden within the Torah itself, and how it all points to trusting the Unseen One who is ultimately in control of the future of His people.

The focus for this study is the amazing reality of this strange festival as it is found hidden within the Torah itself, and how it all points to trusting the Unseen One who is ultimately in control of the future of His people.

A LOT LIKE ATONEMENT

Probably the most startling of these Torah allusions, and in which all are really encapsulated, is the powerful link between the Day of Atonement – Yom Kippur, and Purim. While such a thought might immediately sound like an absurd notion at first, the depths of parallel are astonishing and able to be appreciated once they have been examined.

Probably the most startling of these Torah allusions, and in which all are really encapsulated, is the powerful link between the Day of Atonement – Yom Kippur, and Purim. While such a thought might immediately sound like an absurd notion at first, the depths of parallel are astonishing and able to be appreciated once they have been examined.

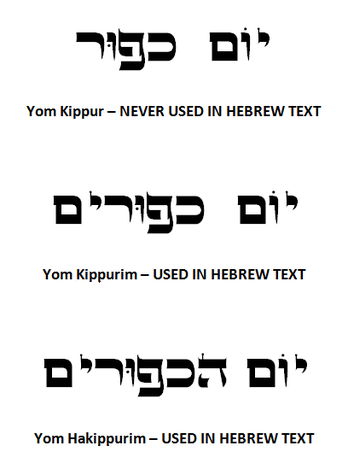

For starters, the title Yom Kippur, while popularly used to reference the day in religious circles and in secular media, is actually somewhat misleading, for the festival is never once spoken of by that designation in the Hebrew Bible. Rather, the day is only ever called in Scripture Yom HaKippurim / Yom Kippurim, which translates out literally into “The Day of Atonements,” or ultra-literally, as “The Day of Coverings.”

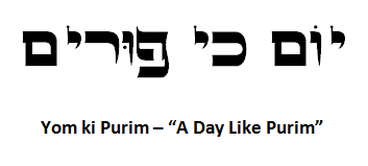

In this manner the link to Purim begins to emerge, if only so initially as a phonetic similarity. When the phrase Yom Kippurim is read aloud in Hebrew, it sounds identical to the phrase Yom ki’Purim, which means literally “The Day Like Purim.” The initial link, therefore, is that the Day of Atonement is “like” Purim. Again, how could this even remotely be true? The Day of Atonement is a day of severe fasting, of repentance and fear, of hope for acceptance and forgiveness of sin. Purim is a day of merry-making, of laughter and frivolity without any cares. So where in the world are the links between the two festival days?

A short list follows of the major parallels between the two days:

A short list follows of the major parallels between the two days:

- In both festivals lots play central roles in determining the fate of the people

- In both festivals the fate of the people stand in the balance; spiritual in the Day of Atonement and physical in Purim.

- In both festivals there is a creature “for YHWH” and one “for Azazel” – the two goats in the Day of Atonement, and righteous Mordechai and wicked Haman in Purim

- In both festivals there is a fast; at Purim it is a fast then a feast, and at Atonement it is a feast before a fast.

- In both festivals there is a hiding taking place – the people's sin is hidden / atoned in the Day of Atonement, and the Presence of the Holy One is hidden / unseen in Purim (this is also another way that Purim is alluded to in the Torah - in Deuteronomy 31:17-18, which contains the phrase HASTEYR ASTEER "shall certainly hide," from the root word SATHAR, meaning “hide,” and being the root of the name Esther).

- In both festivals no one was allowed into the presence of the “King” at just any time. One found transgressing could die.

- In both festivals there is an appeal of one person on behalf of the nation to the king; the high priest at the Day of Atonement and the “high priestess” Queen Esther during Purim.

- In both festivals the “king” is in the inner chamber; the human king in Esther and the Divine Presence in the Holy of Holies.

There are further connections that could be made to show how the two festivals are related in intricate spiritual ways.

But as is seen just from examples shared, there are parallels between the two festivals that show they are linked. In fact, some of the parallels are in reality distinct contrasts which seem to show a mirror image. In this way, we can see that the Day of Atonement is really and truly a day like Purim. It is profound in its impact for us, yet what we see taking place at Purim is also extremely profound, really even to a greater degree! How could this be so? How could Purim be a greater event than the awesome Day of Atonement? What could possibly make this true? Consider this quote:

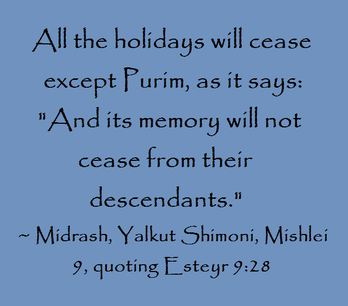

The idea promoted in the quote shared from the Midrash is from ancient Jewish tradition, and speaks to the observance of one sole festival in the World to Come (what comes after the reign of the Messiah - eternity), as opposed to the full spectrum of Scriptural feasts. Why would the tradition ever make this strange claim? Why, of all festivals, would Purim be considered the one that remains when all others fade? There are so many beautiful symbols and facets of the festivals ordained by Yah Himself in the Torah that one could propose would better serve as an eternally-binding observance, so why would they all be passed over and Purim alone be expected to be celebrated forever?

The reason for this thought has to do with the perceived Presence of the Most High in the events of life for His people. At Sinai, when the commandments were given, when the festivals were relayed and the details of Yom Kippurim determined, the experience of the people was like nothing ever before. The overwhelming Presence of the Creator of the universe affected everything. The rabbis go so far as to say that the people were drawing so close to Him with His Presence so near that they almost lost all free will – becoming utterly filled with His Spirit – nearly eradicating their sinful flesh.

In contrast to this is the festival of Purim, where the Presence of Yah is nowhere to be seen on the surface of the text. There is no grand descent of fire and smoke upon Shushan. There is no lightning and voices and thunders shaking the palace of the king of Persia. There are no divine theatrics involved in Purim that can be seen with our eyes. Rather, there is the portrait of a people facing extermination and turning to the Creator with all their hearts, out of their own apparent free will, in fasting and mourning for the hope of survival. What they achieved was the favor from the heavenly court of the Most High for Queen Esther before the human court of man. This displays for us the true power of man being able to become at-one with the Holy One through heartfelt repentance. We can obtain favor when we approach Him if we come with the right spirit.

Know this truth: only ONE fast is ever actually divinely decreed for the people of the Most High: Yom Kippurim. Fasting at other times is indeed permitted, but it is not decreed by heaven for any other time but Yom Kippurim. But with Purim, a fast was decreed by a human heart, and the same type of repentance and prayers went up from the nation of Israel as on Yom Kippurim. Because of the amazing acceptance received from this fast, the austere observance of the day flipped into observance via merrymaking and joy and thanksgiving for life spared. Yom Kippurim is a day where we sanctify ourselves through abstaining from what is permitted. At Purim, the Jewish people also sanctified themselves by what was permitted – to fast. Now, having found acceptance by Yah at the time of Purim, this particular festival transforms into a time of immense joy, and yet in this joy, we are sanctifying ourselves by what is permitted to us, as well – the delights of life. Which of the two could be perceived as a greater accomplishment? Anyone could conceivably deny themselves from the delights of life and in doing so sanctify that specific time. But that is only a passing moment. One cannot exist in a state of fasting. Even Messiah fasted only for a time. He did not live a life of fasting while He was on earth. In contrast, can one partake of the delights of life and in doing sanctify those delights? Could it be done in such a way as to make the common holy? Are we able to elevate the mundane? Can we live a life of sanctification? That is the greater challenge! And so, in Purim, we celebrate that life overcame death, that a man was able to step-up to the decree of the Day of Atonement in himself; he did not receive a divine command to fast and repent, yet did so of his own accord, and received a similar “atonement” by doing so. In this sense, Yom Kippurim is a day like Purim – they are two sides of the same coin, in effect. One is a decree from the Most High, the other, a decree from man.

Understanding these things, we can return to the statement made in the Midrash, and we can see that it is not meant literally, but figuratively: the spiritual reality of Purim is what shall be celebrated, for it speaks of the time when man elevated every action to that of a sanctification-level deed – even the mundane actions of life. It is a prototype of the reality that will be everyday life for us in the World to Come – absolute and undifferentiated holiness. Every act will be uncompromised righteousness. Every thought and deed will be set-apart and pure. The world will be surrounded and permeated by the holiness of His Word made reality! Purim is the one festival that points to this future, because we sanctify ourselves by what is allowed, and in the World to Come, all that we shall do shall be sanctified – sin will be gone!

The idea promoted in the quote shared from the Midrash is from ancient Jewish tradition, and speaks to the observance of one sole festival in the World to Come (what comes after the reign of the Messiah - eternity), as opposed to the full spectrum of Scriptural feasts. Why would the tradition ever make this strange claim? Why, of all festivals, would Purim be considered the one that remains when all others fade? There are so many beautiful symbols and facets of the festivals ordained by Yah Himself in the Torah that one could propose would better serve as an eternally-binding observance, so why would they all be passed over and Purim alone be expected to be celebrated forever?

The reason for this thought has to do with the perceived Presence of the Most High in the events of life for His people. At Sinai, when the commandments were given, when the festivals were relayed and the details of Yom Kippurim determined, the experience of the people was like nothing ever before. The overwhelming Presence of the Creator of the universe affected everything. The rabbis go so far as to say that the people were drawing so close to Him with His Presence so near that they almost lost all free will – becoming utterly filled with His Spirit – nearly eradicating their sinful flesh.

In contrast to this is the festival of Purim, where the Presence of Yah is nowhere to be seen on the surface of the text. There is no grand descent of fire and smoke upon Shushan. There is no lightning and voices and thunders shaking the palace of the king of Persia. There are no divine theatrics involved in Purim that can be seen with our eyes. Rather, there is the portrait of a people facing extermination and turning to the Creator with all their hearts, out of their own apparent free will, in fasting and mourning for the hope of survival. What they achieved was the favor from the heavenly court of the Most High for Queen Esther before the human court of man. This displays for us the true power of man being able to become at-one with the Holy One through heartfelt repentance. We can obtain favor when we approach Him if we come with the right spirit.

Know this truth: only ONE fast is ever actually divinely decreed for the people of the Most High: Yom Kippurim. Fasting at other times is indeed permitted, but it is not decreed by heaven for any other time but Yom Kippurim. But with Purim, a fast was decreed by a human heart, and the same type of repentance and prayers went up from the nation of Israel as on Yom Kippurim. Because of the amazing acceptance received from this fast, the austere observance of the day flipped into observance via merrymaking and joy and thanksgiving for life spared. Yom Kippurim is a day where we sanctify ourselves through abstaining from what is permitted. At Purim, the Jewish people also sanctified themselves by what was permitted – to fast. Now, having found acceptance by Yah at the time of Purim, this particular festival transforms into a time of immense joy, and yet in this joy, we are sanctifying ourselves by what is permitted to us, as well – the delights of life. Which of the two could be perceived as a greater accomplishment? Anyone could conceivably deny themselves from the delights of life and in doing so sanctify that specific time. But that is only a passing moment. One cannot exist in a state of fasting. Even Messiah fasted only for a time. He did not live a life of fasting while He was on earth. In contrast, can one partake of the delights of life and in doing sanctify those delights? Could it be done in such a way as to make the common holy? Are we able to elevate the mundane? Can we live a life of sanctification? That is the greater challenge! And so, in Purim, we celebrate that life overcame death, that a man was able to step-up to the decree of the Day of Atonement in himself; he did not receive a divine command to fast and repent, yet did so of his own accord, and received a similar “atonement” by doing so. In this sense, Yom Kippurim is a day like Purim – they are two sides of the same coin, in effect. One is a decree from the Most High, the other, a decree from man.

Understanding these things, we can return to the statement made in the Midrash, and we can see that it is not meant literally, but figuratively: the spiritual reality of Purim is what shall be celebrated, for it speaks of the time when man elevated every action to that of a sanctification-level deed – even the mundane actions of life. It is a prototype of the reality that will be everyday life for us in the World to Come – absolute and undifferentiated holiness. Every act will be uncompromised righteousness. Every thought and deed will be set-apart and pure. The world will be surrounded and permeated by the holiness of His Word made reality! Purim is the one festival that points to this future, because we sanctify ourselves by what is allowed, and in the World to Come, all that we shall do shall be sanctified – sin will be gone!

THE CONFLICT

When we look at the conflict taking place in the book of Esther, the sole reason for the festival of Purim, we see that it centers on the death-wish of the wicked Haman for the Jewish people living in Persia. His hatred for the Jewish people was brutal and deep-seated. On the surface, it likely sprang from his ancestor’s link to the people of Israel. Centuries before, his ancestor Agag, who was king of the Amaleqites, was hacked to death by Samuel the prophet after the first king of Israel, Saul the Benjaminite, slaughtered his other ancestors, but had decided to spare his life.

When we look at the conflict taking place in the book of Esther, the sole reason for the festival of Purim, we see that it centers on the death-wish of the wicked Haman for the Jewish people living in Persia. His hatred for the Jewish people was brutal and deep-seated. On the surface, it likely sprang from his ancestor’s link to the people of Israel. Centuries before, his ancestor Agag, who was king of the Amaleqites, was hacked to death by Samuel the prophet after the first king of Israel, Saul the Benjaminite, slaughtered his other ancestors, but had decided to spare his life.

And Saul struck the Amaleqites from Khavilah until you come to Shur, that is over against Egypt. And he took Agag, the king of the Amaleqites, alive, and completely destroyed all the people with the edge of the sword.

~ 1 Samuel 15:7-8

Now why did Saul perform this nigh-eradication of the people of Amaleq? His actions stem from a commandment given in the Torah itself concerning this very people.

Remember what Amaleq did to you on the way, when you were come out of Egypt; How he met you on the way, and struck at your back, even all the feeble at the rear, when you were tired and weary; and he did not fear Elohim. Therefore it shall be, when YHWH your Elohim has given you rest from all of your enemies around you, in the land which YHWH your Elohim gives you for an inheritance to possess it, that you do blot out the memory of Amaleq from under heaven: you shall not forget!

~ Deuteronomy 25:17-19

Therefore, by looking at this historical reality, we can see that Haman’s hatred was understood. He hated the people of Yeesra’El because they would be at war until one of them was utterly destroyed. It is of interest that the people were called to destroy the memory of Amaleq – to blot out that memory. It is a commandment by Yah to do this. However, we know that Sha’ul got so close yet failed to complete the task. That led to Agag fathering a child before his death at the hand of Sh’mu’El, and thus Amaleq remained. This leads us ultimately to the book of Esteyr, to Haman, a descendant of Amaleq, and to an account where the Name of Yah is effectively blotted-out. So if we let evil continue it will persecute the good. We won’t be able to see the Presence of our Maker at work in our lives. Evil blinds us to His reality.

The wickedness and hatred of Haman had a place, to be sure, but it surpassed just a racial memory of war and enmity fueling the fires of Haman’s hate. Rather, this unique enmity can actually be traced back to the very beginning of all things.

~ 1 Samuel 15:7-8

Now why did Saul perform this nigh-eradication of the people of Amaleq? His actions stem from a commandment given in the Torah itself concerning this very people.

Remember what Amaleq did to you on the way, when you were come out of Egypt; How he met you on the way, and struck at your back, even all the feeble at the rear, when you were tired and weary; and he did not fear Elohim. Therefore it shall be, when YHWH your Elohim has given you rest from all of your enemies around you, in the land which YHWH your Elohim gives you for an inheritance to possess it, that you do blot out the memory of Amaleq from under heaven: you shall not forget!

~ Deuteronomy 25:17-19

Therefore, by looking at this historical reality, we can see that Haman’s hatred was understood. He hated the people of Yeesra’El because they would be at war until one of them was utterly destroyed. It is of interest that the people were called to destroy the memory of Amaleq – to blot out that memory. It is a commandment by Yah to do this. However, we know that Sha’ul got so close yet failed to complete the task. That led to Agag fathering a child before his death at the hand of Sh’mu’El, and thus Amaleq remained. This leads us ultimately to the book of Esteyr, to Haman, a descendant of Amaleq, and to an account where the Name of Yah is effectively blotted-out. So if we let evil continue it will persecute the good. We won’t be able to see the Presence of our Maker at work in our lives. Evil blinds us to His reality.

The wickedness and hatred of Haman had a place, to be sure, but it surpassed just a racial memory of war and enmity fueling the fires of Haman’s hate. Rather, this unique enmity can actually be traced back to the very beginning of all things.

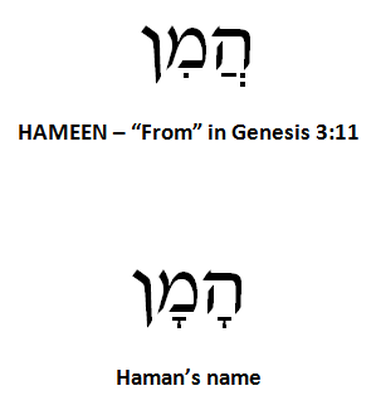

In the book of Genesis 3:11, we read the following words from Elohim:

And He said, “Who told you that you were naked? From the tree which I commanded you to not eat from have you eaten?”

The first time we see the term “from” it is HAMEEN. It is spelled exactly the same as the name Haman, only pronounced differently. So literally, to partake “from” the tree of the knowledge of good and evil is to be like Haman. When we look at the methodology of Haman, we can see this very nature at work. He used his cunning knowledge to choose a date for the destruction of the Jewish people with the pur – the lot – and it became the day of his own death. He used his cunning to pronounce the reward for a man the king would greatly honor, believing it to be himself, and it turned out to be Mordechai. He used his cunning to devise a mode of death for Mordechai, and it turned on him. He used his “cunning” to attack Queen Esther, and it led to his being caught red-handed by the king himself. His nature aptly displays that of a person who is striving to excel in life by means of the knowledge of good and evil. Just like part of the natural consequence of partaking of the fruit of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil was the perversion of good plant to that of thorn – so too were his actions intended for his own good yet producing only curse.

The Jewish people – and all who will come to the Creator through the Messiah, have been called to choose life – that is, the tree of life, the symbol for the means for eternal life. We cannot place our hope in discerning the intricacies of good and evil, of thinking that if we can just “know” what is right and wrong that we will be okay. That will not cut it, because that is the way of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil. That is the way of Haman. What we need is not knowledge of good and evil, but life. We need life, and we can only attain it by coming to Him for that life. The fruit of the tree of life will always produce a tree of life – a continuation of what came before. We are called to be trees of righteousness, to partake of life and let it conform us to that image. So we can go the way of Haman and revel in curse and thorn, or we can go the way of life and be planted firmly as the tree of life.

We can see that the hatred of Haman was founded in trying to live a life with boundaries set in knowledge alone, and not in the desire for true life. Thinking of Yom Kippurim’s link to Purim, and the link of the tree to Haman, we can begin to see the links develop even further when we realize that there were two trees in the Garden; the tree of life and the tree of the knowledge of good and evil. If the one symbolized Haman and thus the goat for Azazel, then the other must symbolize the goat for YHWH and Mordechai – who was the reason Esther took action in the first place.

This contrast between what it means to live a life following the path of life and that following the path of the knowledge of good and evil can be seen elsewhere in Scripture with the account where the conflict of Purim really begins to take shape: the relationship between the brothers Esau and Jacob. Esau is the ancestor of Amaleq – his grandfather, to be exact. Amaleq is a far-removed ancestor of Haman, as has already been discussed. Jacob is the ancestor to Mordechai and Esther and the rest of the Hebrew people living in Persia.

When we look at the relationship between Esau and Jacob, we can see where and how the parallels began. Looking at the first recorded instance of discord between the brothers, we find a link arising in Genesis 25:34:

And He said, “Who told you that you were naked? From the tree which I commanded you to not eat from have you eaten?”

The first time we see the term “from” it is HAMEEN. It is spelled exactly the same as the name Haman, only pronounced differently. So literally, to partake “from” the tree of the knowledge of good and evil is to be like Haman. When we look at the methodology of Haman, we can see this very nature at work. He used his cunning knowledge to choose a date for the destruction of the Jewish people with the pur – the lot – and it became the day of his own death. He used his cunning to pronounce the reward for a man the king would greatly honor, believing it to be himself, and it turned out to be Mordechai. He used his cunning to devise a mode of death for Mordechai, and it turned on him. He used his “cunning” to attack Queen Esther, and it led to his being caught red-handed by the king himself. His nature aptly displays that of a person who is striving to excel in life by means of the knowledge of good and evil. Just like part of the natural consequence of partaking of the fruit of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil was the perversion of good plant to that of thorn – so too were his actions intended for his own good yet producing only curse.

The Jewish people – and all who will come to the Creator through the Messiah, have been called to choose life – that is, the tree of life, the symbol for the means for eternal life. We cannot place our hope in discerning the intricacies of good and evil, of thinking that if we can just “know” what is right and wrong that we will be okay. That will not cut it, because that is the way of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil. That is the way of Haman. What we need is not knowledge of good and evil, but life. We need life, and we can only attain it by coming to Him for that life. The fruit of the tree of life will always produce a tree of life – a continuation of what came before. We are called to be trees of righteousness, to partake of life and let it conform us to that image. So we can go the way of Haman and revel in curse and thorn, or we can go the way of life and be planted firmly as the tree of life.

We can see that the hatred of Haman was founded in trying to live a life with boundaries set in knowledge alone, and not in the desire for true life. Thinking of Yom Kippurim’s link to Purim, and the link of the tree to Haman, we can begin to see the links develop even further when we realize that there were two trees in the Garden; the tree of life and the tree of the knowledge of good and evil. If the one symbolized Haman and thus the goat for Azazel, then the other must symbolize the goat for YHWH and Mordechai – who was the reason Esther took action in the first place.

This contrast between what it means to live a life following the path of life and that following the path of the knowledge of good and evil can be seen elsewhere in Scripture with the account where the conflict of Purim really begins to take shape: the relationship between the brothers Esau and Jacob. Esau is the ancestor of Amaleq – his grandfather, to be exact. Amaleq is a far-removed ancestor of Haman, as has already been discussed. Jacob is the ancestor to Mordechai and Esther and the rest of the Hebrew people living in Persia.

When we look at the relationship between Esau and Jacob, we can see where and how the parallels began. Looking at the first recorded instance of discord between the brothers, we find a link arising in Genesis 25:34:

And Jacob gave to Esau bread and lentil stew, and he ate and drank, and arose, and walked away, and Esau despised the birthright.

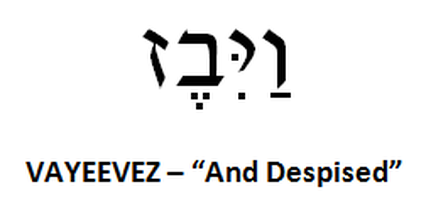

This matter is where it really all begins to take shape. The wilely nature of Jacob is always to be questioned, yet the purpose behind his actions is clear: he valued the birthright. Esau, we are told, "despised" the birthright. The word "despised" here is VAYEEVEZ. Although the term is found scattered all over the pages of Hebrew Scripture, the way it is inflected grammatically is of note, because there is only one other instance in all of the Word where it is spelled exactly the same way: Esther 3:6 –

And it was despicable in his eyes to send forth his hand upon Mordechai only, for they had told him of Mordechai's people. And Haman searched to destroy all the Jews which were in all the kingdom of Akhashveyrosh – Mordechai’s people!

The phrase “and it was despicable” is VAYEEVEZ. The same despising that Esau had towards his birthright was the same despising Haman had toward the Jewish people. Notice that it was of no value to Haman to kill Mordechai only – for that is the intent of the context. He despised the thought of doing away with just one man when an entire people lay at his fingertips. Here’s the important linking factor to understand here: Haman had the legal right to do away with Mordechai for not bowing to him – for to bow was an edict of the king himself! This is clearly stated in Esther 3:2. Mordechai knew exactly what he was doing by not bowing – he took his own life in his hands (this factor of not bowing shall be returned to later, for there is much to glean from this truth). So just as the birthright was Esau’s and he despised it, so too was Mordechai’s life rightly forfeit when he refused to bow to Haman, and yet Haman despised the thought of just killing one man! This shows truly the depth of his evil. So Haman gave up the right to justly kill Mordechai when he decided to implement a plan to kill all the Jewish people. Thus, the despising of Esau and the despising of Haman are extremely similar in nature: they had total control of the situation, yet gave up having the upper-hand, losing everything for doing so. Another way also did Haman link to Esau, in that he despised his own birthright, for he is stated to be a descendant of Agag, an Amaleqite king, and thus, is himself an heir to the throne – which would be his by birthright. But instead of being content with his own status, he sought to destroy those who had stolen status from his ancestor Esau so many generations before.

Another amazing linking factor in the story of Esau and Jacob is the second time that Jacob displays his desire for obtaining the birthright that he valued so very much. That particular passage is found in Genesis 27:9 –

Go now, unto the flock, and take for me two kids – good goats, and I shall make them tasty for your father, as that he loves.

This matter is where it really all begins to take shape. The wilely nature of Jacob is always to be questioned, yet the purpose behind his actions is clear: he valued the birthright. Esau, we are told, "despised" the birthright. The word "despised" here is VAYEEVEZ. Although the term is found scattered all over the pages of Hebrew Scripture, the way it is inflected grammatically is of note, because there is only one other instance in all of the Word where it is spelled exactly the same way: Esther 3:6 –

And it was despicable in his eyes to send forth his hand upon Mordechai only, for they had told him of Mordechai's people. And Haman searched to destroy all the Jews which were in all the kingdom of Akhashveyrosh – Mordechai’s people!

The phrase “and it was despicable” is VAYEEVEZ. The same despising that Esau had towards his birthright was the same despising Haman had toward the Jewish people. Notice that it was of no value to Haman to kill Mordechai only – for that is the intent of the context. He despised the thought of doing away with just one man when an entire people lay at his fingertips. Here’s the important linking factor to understand here: Haman had the legal right to do away with Mordechai for not bowing to him – for to bow was an edict of the king himself! This is clearly stated in Esther 3:2. Mordechai knew exactly what he was doing by not bowing – he took his own life in his hands (this factor of not bowing shall be returned to later, for there is much to glean from this truth). So just as the birthright was Esau’s and he despised it, so too was Mordechai’s life rightly forfeit when he refused to bow to Haman, and yet Haman despised the thought of just killing one man! This shows truly the depth of his evil. So Haman gave up the right to justly kill Mordechai when he decided to implement a plan to kill all the Jewish people. Thus, the despising of Esau and the despising of Haman are extremely similar in nature: they had total control of the situation, yet gave up having the upper-hand, losing everything for doing so. Another way also did Haman link to Esau, in that he despised his own birthright, for he is stated to be a descendant of Agag, an Amaleqite king, and thus, is himself an heir to the throne – which would be his by birthright. But instead of being content with his own status, he sought to destroy those who had stolen status from his ancestor Esau so many generations before.

Another amazing linking factor in the story of Esau and Jacob is the second time that Jacob displays his desire for obtaining the birthright that he valued so very much. That particular passage is found in Genesis 27:9 –

Go now, unto the flock, and take for me two kids – good goats, and I shall make them tasty for your father, as that he loves.

This is Jacob’s mother Rebekah commanding her son to do this action. Jacob is to take two young goats and bring them in for slaughter. Interestingly, there is only one other time in Scripture when two kid goats are used, and that is in the ceremony commanded to be done for Yom Kippurim! Two kid goats are brought before the high priest – one for Azazel and one for YHWH, and atonement is made through the actions that proceed to take place from that point on. Understanding this, it becomes very significant to realize that when Jacob goes in to be blessed with the birthright blessing that belonged to his brother Esau, he was wearing the hairy skins which had just been on at the kid goats his mother had cooked (see 27:16)! He received the blessing, and thus, he symbolized the goat for YHWH that would later be the only goat offered for sin on Yom Kippurim!

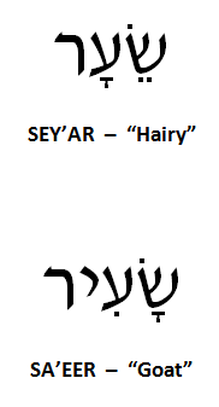

The fate of the other goat, we know, at least Scripturally, was to be sent off into the wilderness. This symbolized Esau. Indeed, Esau is even first called “hairy” in Scripture in 25:25, and there the word is SEY’AR, which is also a root word for “goat” - SA'EER! The two sons come before their father, and they are both technically “goats!” This mirrors Leviticus 16 and the Yom Kippurim ceremony of the two goats, which uses the same word for "goat" in that passage (Hebrew has different terms for the word “goat,” so this is significant!).

The conflict which had existed between the two brothers had now escalated to a height where Esau desired to kill Jacob for his deception. It is important to note that the actions of Jacob were not based off of living a life by the knowledge of good and evil. Rather, his actions were founded on his desire for the birthright, which he valued above all else. A life lived according to the knowledge of good and evil would tell you that doing what he did had consequences which would lead to being cursed if he was found out before the blessing had been given, and even after, when it had already taken place, he would have to suffer untold consequences in regards to what kinds of reactions might result from his deception. So, Jacob was not living according to the knowledge of good and evil. Rather, his actions fell in line with the tree of life – a path that doesn’t always fit the wisdom we see when we try to discern just good and evil.

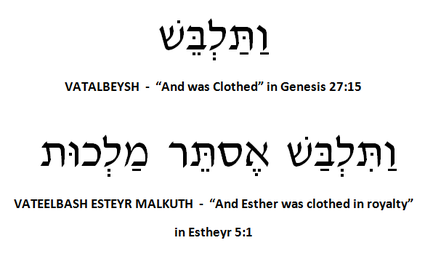

Moreover, he was concealed in the garments of his brother and in goat-hair; he looked like one thing but was really another! This exemplifies the person of Esther so radically, as she was a Jewish girl named Hadassah, who took on the Persian name of Esther, blending in with the populace, and eventually became a Persian queen! She could have been open and revealed who she really was, and would not have attained the throne or been able to save her people. No, she acted in a way that was following life and not a life based on the knowledge of good and evil. Additionally, when Jacob is dressed by his mother in the garments of his brother in 27:15, it uses the term VATALBEYSH, and outside of the Torah, it appears only one other time in Hebrew Scripture spelled exactly like this, in Esther 5:1 –

The conflict which had existed between the two brothers had now escalated to a height where Esau desired to kill Jacob for his deception. It is important to note that the actions of Jacob were not based off of living a life by the knowledge of good and evil. Rather, his actions were founded on his desire for the birthright, which he valued above all else. A life lived according to the knowledge of good and evil would tell you that doing what he did had consequences which would lead to being cursed if he was found out before the blessing had been given, and even after, when it had already taken place, he would have to suffer untold consequences in regards to what kinds of reactions might result from his deception. So, Jacob was not living according to the knowledge of good and evil. Rather, his actions fell in line with the tree of life – a path that doesn’t always fit the wisdom we see when we try to discern just good and evil.

Moreover, he was concealed in the garments of his brother and in goat-hair; he looked like one thing but was really another! This exemplifies the person of Esther so radically, as she was a Jewish girl named Hadassah, who took on the Persian name of Esther, blending in with the populace, and eventually became a Persian queen! She could have been open and revealed who she really was, and would not have attained the throne or been able to save her people. No, she acted in a way that was following life and not a life based on the knowledge of good and evil. Additionally, when Jacob is dressed by his mother in the garments of his brother in 27:15, it uses the term VATALBEYSH, and outside of the Torah, it appears only one other time in Hebrew Scripture spelled exactly like this, in Esther 5:1 –

And it came to be it was at the third day, and Esther was clothed royally, and stood in the court of the House of the King, at the innermost, across from the House of the King, and the King sat upon the royal throne in the House of Royalty, across from the door of the House.

This link shows Esther as Jacob, taking a chance while knowing she could easily perish, being a Jewish woman with a decree of death set against her, yet clothed as a queen! But she went, like Jacob did who valued the birthright, with an attitude founded in hope. In fact, the very wording in Hebrew is rather strange concerning her dress choice. It says in Hebrew: VATEELBASH ESTEYR MALKUTH – the final term MALKUTH literally means “kingdom / reign / realm.” By stating it this way, and linking it to the act of Jacob, we can see that she came with the mindset of the Kingdom – she came valuing the birthright of Israel in the earth as a necessary nation for not just righteousness, but ultimately, for life to come through Messiah’s coming!

So up to this point in the history of the conflict there have been sins on both sides – neither escapes doing evil. As humans we are unfortunately partakers of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, and yet, like Jacob and so many others, we can choose to not follow that path, and follow life instead. Jacob had shown himself dedicated to following that path of life, but as the years pass when he is away from his brother, he allows his fear to remain, and upon his return to the land twenty years afterwards, acts in a much different fashion towards Esau than before. We read of the account in Genesis 33:2-7.

This link shows Esther as Jacob, taking a chance while knowing she could easily perish, being a Jewish woman with a decree of death set against her, yet clothed as a queen! But she went, like Jacob did who valued the birthright, with an attitude founded in hope. In fact, the very wording in Hebrew is rather strange concerning her dress choice. It says in Hebrew: VATEELBASH ESTEYR MALKUTH – the final term MALKUTH literally means “kingdom / reign / realm.” By stating it this way, and linking it to the act of Jacob, we can see that she came with the mindset of the Kingdom – she came valuing the birthright of Israel in the earth as a necessary nation for not just righteousness, but ultimately, for life to come through Messiah’s coming!

So up to this point in the history of the conflict there have been sins on both sides – neither escapes doing evil. As humans we are unfortunately partakers of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, and yet, like Jacob and so many others, we can choose to not follow that path, and follow life instead. Jacob had shown himself dedicated to following that path of life, but as the years pass when he is away from his brother, he allows his fear to remain, and upon his return to the land twenty years afterwards, acts in a much different fashion towards Esau than before. We read of the account in Genesis 33:2-7.

Jacob, letting his fear conquer his faith, chooses to act the path of the knowledge of good and evil, and reacts to meeting Esau in a striking manner – he and his entire family bow to his brother! Everyone from his wives to his wives’ handmaids, to his children – his entire family places themselves at the mercy of Esau. Now, to his credit, Esau does not murder them, but it should not go unnoticed that Jacob’s entire family bowed to Esau.

NOT ABOUT TO BOW

In our understanding of this conflict, then, we return to the book of Esther and the events that eventually lead up to Purim, and the major factor in the book is that found in 3:2, where Mordechai refuses to bow to Haman. The term is of interest grammatically, for it is YEEK’RA, and is in the imperfect tense in Hebrew. This tense is used to display something that will be done – a future tense, in a way. Although the reference made is to a past bowing, the tense of the verb speaks to a future action. This grammatical function means that if it is in future tense in the past, and it didn’t happen in the past, then it won’t happen in the future. In other words, not only did Mordechai not bow to Haman, he would never bow to Haman!

NOT ABOUT TO BOW

In our understanding of this conflict, then, we return to the book of Esther and the events that eventually lead up to Purim, and the major factor in the book is that found in 3:2, where Mordechai refuses to bow to Haman. The term is of interest grammatically, for it is YEEK’RA, and is in the imperfect tense in Hebrew. This tense is used to display something that will be done – a future tense, in a way. Although the reference made is to a past bowing, the tense of the verb speaks to a future action. This grammatical function means that if it is in future tense in the past, and it didn’t happen in the past, then it won’t happen in the future. In other words, not only did Mordechai not bow to Haman, he would never bow to Haman!

How can Mordechai not only not bow to Haman in this one incident, but never again bow to Haman? Remember how Jacob and his entire family bowed to Esau? But, the designation “entire” is a misnomer. One son of Jacob had no part in the bowing: Benjamin! Benjamin was not yet even born! He alone of the sons did not willfully participate in the bowing to Esau. So when we go to the book of Esther, we must take notice of which tribe Mordechai belongs: Benjamin (see 2:5)! Truly, therefore, Mordechai had never bowed down to Haman, and never would bow down to Haman! The tribe of Benjamin was the only tribe who had never willingly placed themselves under the authority of Esau, and therefore, it was Benjamin who would destroy the misplaced authority in time to come.

Looking at Mordechai symbolically, we see him as the type of Yeshua who stands to mediate for the people. He is the initial mover for righteousness. He is of the tribe of Benjamin, which never bowed to Esau, and whose tribal name means (Son of the Right Hand), and so too is Messiah Yeshua the One who never shared in the sin of Adam, and who is truly the Son of Elohim’s right hand! Yeshua intercedes for us, pushing us to take a stand and be of worth to this world, to save lives. Although Mordechai is from Benjamin, we are also told he is a Jewish man. This means his parentage came from both tribes. This parallels Yeshua, whose parentage was dual – the Spirit and Mary. Interestingly, just as Esther who was not supposed to enter the inner chamber of the king or she could face death, so too are the tribal allotments for Judah and Benjamin those of the Temple Mount, although they are not priests and cannot serve there. In fact, the area of the Holy of Holies actually falls into the tribal allotment of Benjamin! This means that although they should not be able to officiate, the portion is still theirs, and they have a say if the ear of the King will but listen to their words. Yeshua, in like manner, is not a Levitical priest, yet He came as a priest interceding for the people, and was accepted!

Looking at Mordechai symbolically, we see him as the type of Yeshua who stands to mediate for the people. He is the initial mover for righteousness. He is of the tribe of Benjamin, which never bowed to Esau, and whose tribal name means (Son of the Right Hand), and so too is Messiah Yeshua the One who never shared in the sin of Adam, and who is truly the Son of Elohim’s right hand! Yeshua intercedes for us, pushing us to take a stand and be of worth to this world, to save lives. Although Mordechai is from Benjamin, we are also told he is a Jewish man. This means his parentage came from both tribes. This parallels Yeshua, whose parentage was dual – the Spirit and Mary. Interestingly, just as Esther who was not supposed to enter the inner chamber of the king or she could face death, so too are the tribal allotments for Judah and Benjamin those of the Temple Mount, although they are not priests and cannot serve there. In fact, the area of the Holy of Holies actually falls into the tribal allotment of Benjamin! This means that although they should not be able to officiate, the portion is still theirs, and they have a say if the ear of the King will but listen to their words. Yeshua, in like manner, is not a Levitical priest, yet He came as a priest interceding for the people, and was accepted!

So, Purim is the hidden festival of the Torah – the final celebration of the redemptive plan of Elohim in the earth. Just as we see only glimpses of how it will all come together, and must rely not on our knowledge of good and evil, but on the sovereign One who gives us spiritual life, so too does this historical account display for us the hidden Presence of Yah amongst His people. He may be hiding, but He is still here. As we know that all things are working for the good, we can therefore know that He truly is active and aware of the present situation. Because of that, even when we may not be able to discern His presence, we should do all that we have in our power to sanctify our lives, to make ourselves holy by every facet and with every word and deed – for that is the goal of all things, ultimately – to exist in total harmony with our Creator once more.

All study contents Copyright Jeremy Chance Springfield, except for graphics and images, which are Copyright their respective creators.