THE THRONE OF MOSES

by Jeremy Chance Springfield

1/1/2024

Near the end of Yeshua’s earthly ministry to Israel He was deliberately tested by the ruling religious class—the Pharisees and the Sadducees. Matthew 22 records the interactions within the Temple of His engagements with the dissenting groups, where He bested them with unmatched displays of Scriptural logic and rabbinic interpretation.

Both parties of religious leaders were single-handedly humbled by Messiah through His discerning use of Scriptural truths. Whereas the groups held the role of trusted spiritual authorities for the people, Yeshua’s sublime judgment and handling of Scripture shows just how important the proper function of the religious authority is for the Creator’s people.

Both parties of religious leaders were single-handedly humbled by Messiah through His discerning use of Scriptural truths. Whereas the groups held the role of trusted spiritual authorities for the people, Yeshua’s sublime judgment and handling of Scripture shows just how important the proper function of the religious authority is for the Creator’s people.

|

This context is important to grasp when we move into the content of Matthew 23. Without any break in setting, the chapter picks up with a progressive escalation of the situation recorded in the previous chapter. Matthew 23 contains Yeshua’s fomenting declarations that quickly intensify into a lengthy and bombastic philippic against the Pharisees and their abusive hypocrisy toward the people of Israel. The Messiah initiates that relentless diatribe, however, with a surprising admission often misunderstood, but which merits our sincere focus.

|

His words in Matthew 23:1-5 have long been a source of sustained disagreement among believers. This study will seek to judiciously address the controversial passage with the hope to bring some sense of clarity that will ultimately be seen as dependent on the specific context mentioned above. The passage will be divided up into three sections to properly address the nuances of Yeshua's words.

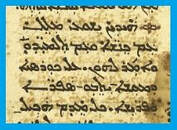

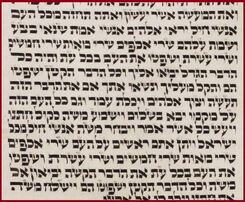

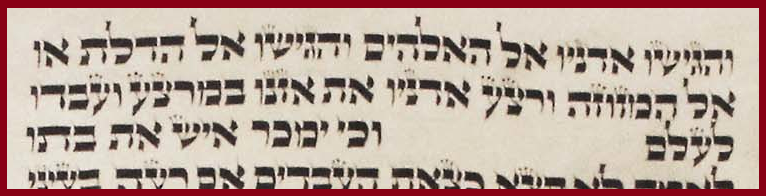

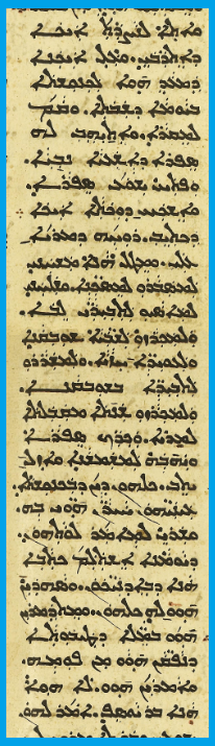

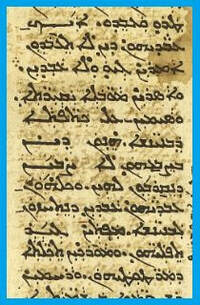

Consider first Matthew 23:1-2 as it is preserved in the ancient Aramaic of the Peshitta text.

Consider first Matthew 23:1-2 as it is preserved in the ancient Aramaic of the Peshitta text.

Having summarily dissuaded the Pharisees and Sadducees from further testing Him, Yeshua suddenly affirms the unique position of the scribes and PRISHE - Aramaic for "Pharisees" - as being seated upon the KURSYA D'MUSHE “throne of Moses.”

The majority will immediately recognize the phrase in its popular rendering as “seat of Moses.” This comes from the reading preserved in the Greek manuscripts of Matthew 23:2, which has the term KATHEDRAS “seat of,” from the noun KATHEDRA “seat.”

If the term KATHEDRA seems familiar, that is because it is the basis for a word made popular in Roman Catholic Christianity: Cathedral—that is, “Place of the Seat.” This refers to what Roman Catholic Christians call the Sancta Sedes, or “Holy See,” meaning “Holy Seat [of authority]”—from whence the Pope operates in his ecclesiastical role for Roman Catholic Christians. Its usage here, obviously, has nothing to do with that much later development.

The precise meaning of this phrase “seat of Moses” as it exists in Matthew 23:2 has long generated debate among believers: is it to be understood literally or figuratively? Was this an actual chair of some type, or an idiom for something else? The answer--and the significance of Yeshua's words--can be found by looking into the Torah as well as examining other ancient Jewish religious texts and historical factors.

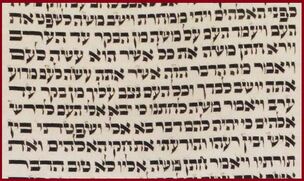

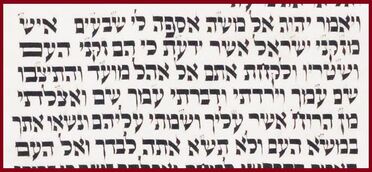

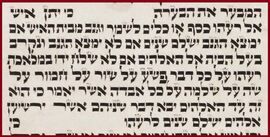

Let us look first into the Torah itself, and we will find a very important passage in Exodus 18:13-16 introducing the concept of the “throne of Moses.”

The precise meaning of this phrase “seat of Moses” as it exists in Matthew 23:2 has long generated debate among believers: is it to be understood literally or figuratively? Was this an actual chair of some type, or an idiom for something else? The answer--and the significance of Yeshua's words--can be found by looking into the Torah as well as examining other ancient Jewish religious texts and historical factors.

Let us look first into the Torah itself, and we will find a very important passage in Exodus 18:13-16 introducing the concept of the “throne of Moses.”

13 And it was in the morning, and Mosheh sat to judge the people, and the people stood by Mosheh from the dawn unto the dusk.

15 And Mosheh said to his father-in-law, “It is because the people come unto me to inquire of [the] Deity.

16 When a matter is for them, they come unto me, and I judge between a man and between his fellow, and I make known the statutes of the Deity, and His Torah.”

16 When a matter is for them, they come unto me, and I judge between a man and between his fellow, and I make known the statutes of the Deity, and His Torah.”

After crossing the Red Sea and approaching Mount Sinai, the people of Israel soon found themselves attempting to live as a community cognizant of their Creator leading them and desiring they behave in a righteous manner. This new situation brought with it much uncertainty, for they were learning afresh how to live as a holy people, which inevitably engendered questions on how that would look like in reality. Since the only man who had intimate access to the Almighty was Moses, they brought their questions and circumstances to him for clarity and instruction going forward. The Hebrew phrase Moses used of what the people were coming to him for is LIDROSH ELOHIM “to inquire of [the] Deity.”

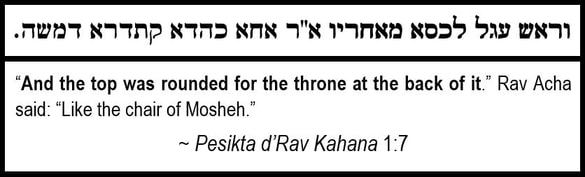

This phrase is important to remember, as we shall see it is used later in various forms to address people seeking out trusted spiritual sources who could clarify diverse situations. Hence, Moses undertook this role as arbiter of the will of heaven on earth while sitting upon a seat of some type. The text is silent as to what he sat upon, but we do possess a preserved text providing further information on it--Pesikta d’Rav Kahana 1:7.

The context here quotes initially a passage describing the throne of King Solomon, which is mentioned in 1st Kings 10:19. It then explains the royal throne was patterned in a general way after what the Aramaic text refers to as KATHIDRA D’MOSHEH the “chair of Mosheh.” The Torah commands that the king of Israel to be seated upon a throne, but does not explain why this is necessary [see: Deuteronomy 17:18]. The answer is found in the traditional Jewish view that Moses acted in the office of the king over Israel [see: Mishnah, Shevuot 2:2, Talmud Yerushalmi, Sanhedrin 1:3, Talmud Bavli, Zevachim 102a, Shemot Rabbah 40:2, among many others]. Knowing he was seated on a throne to clarify the Torah for Israel makes sense as to the Torah's command that an Israelite king also be seated upon a throne and read there from the Torah, and why the historical details reveal Solomon patterned his throne after the throne of Moses.

The term KATHIDRA is merely the Aramaic pronunciation of the aforementioned Greek word KATHEDRA “seat.” In this we have a direct parallel to the “seat of Moses” mentioned in Matthew 23:2.

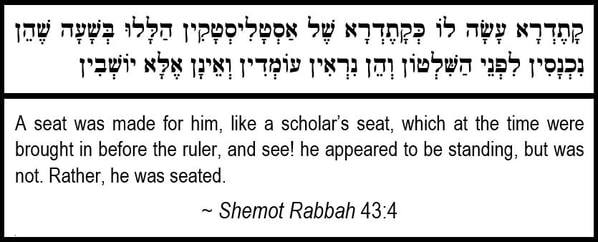

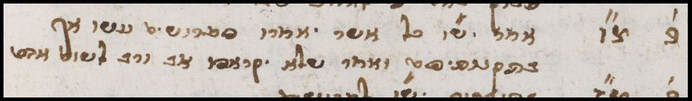

A secondary mention is found in Shemot Rabbah 43:4, further describing the chair in which Moses was seated.

A secondary mention is found in Shemot Rabbah 43:4, further describing the chair in which Moses was seated.

From the Jewish interpretation, the phrase “throne of Moses” / “seat of Moses” is interchangeable and unquestionably intended to refer to a literal seat upon which the authoritative lawgiver sat to address the various aspects of a people striving to live a holy life.

Returning now to the account from Exodus 18 and the conversation between Moses and Jethro, we find that his father-in-law viewed the constant arbitration required of Moses to be a detriment to his calling as shepherd over the entire people, and suggested another course of action for his son-in-law, which is recorded in Exodus 18:21-26.

21 “And you shall discern from all the people men of might, fearers of [the] Deity—men of truth, hating greed—and appoint them over them: rulers of thousands, rulers of hundreds, rulers of fifties, and rulers of tens.

22 And they shall judge the people all the time. And it shall be every matter that is great they bring to unto you, and ever matter that is small they shall judge, and it shall be easier concerning you, and they shall bear it with you.

22 And they shall judge the people all the time. And it shall be every matter that is great they bring to unto you, and ever matter that is small they shall judge, and it shall be easier concerning you, and they shall bear it with you.

25 And Mosheh chose men of might from all Yisra’el and made them leaders over the people: rulers of thousands, rulers of hundreds, rulers of fifties, and rulers of tens.

26 And they judged the people at all times. The difficult matter they brought to Mosheh, and every small matter they judged themselves.

26 And they judged the people at all times. The difficult matter they brought to Mosheh, and every small matter they judged themselves.

The appointing of special agents to act in his stead meant that Moses delegated not only his authority to judge, but his very spiritual insight to them. It would have been necessary for Moses to instruct them on how to litigate the broad spectrum of needs that would be brought before them. To be clear about the unique situation they were in, this is wholly prior to the Torah being given at Sinai to the nation. Whatever details Moses was relaying to the people are not necessarily preserved in the text of the Torah, for it was a progressive revelation occurring over the span of forty days beyond the initial giving of the Ten Commandments. This detail is why Jethro said Moses must “discern” the men from the rest of the people, being careful that they met specific moral and spiritual standards in order to perform their judicial duty without guile or fear of corruption.

This selection by Moses at the recommendation of his father-in-law is significant, for in it is the authority to teach and instruct being transmitted from the individual who was in direct contact with the Creator to those who had to trust his relationship and subsequently be trusted to relay that special knowledge accurately to others. This is a monumental task, to be sure, and beyond the scope of mere human delegation dynamics.

For this reason, we read in Numbers 11:16-17 that the Holy One fulfilled Jethro’s conditional “if” of Exodus 18:23 and had an incredible mercy on Moses to ordain seventy men to receive a special spiritual anointing to support the leading of the entire nation.

This selection by Moses at the recommendation of his father-in-law is significant, for in it is the authority to teach and instruct being transmitted from the individual who was in direct contact with the Creator to those who had to trust his relationship and subsequently be trusted to relay that special knowledge accurately to others. This is a monumental task, to be sure, and beyond the scope of mere human delegation dynamics.

For this reason, we read in Numbers 11:16-17 that the Holy One fulfilled Jethro’s conditional “if” of Exodus 18:23 and had an incredible mercy on Moses to ordain seventy men to receive a special spiritual anointing to support the leading of the entire nation.

17 And I shall descend and speak with you there, and I shall take from the Spirit which is upon you, and shall appoint it upon them, and the people shall bear with you the burden, and you shall not bear it by yourself.”

The passage continues and reveals in Numbers 11:25 that these seventy elders received the Spirit to judge along with Moses. This development is vital to perceive: the supernal power given to Moses was shared with seventy of his peers. With the Spirit thus guiding them, they could likewise perform judgment in verity. We find Moses reminded the people decades later as they prepared to enter the land of promise that he had sought their best interest regarding the execution of true justice in their midst, as we read in Deuteronomy 1:15-17.

15 And I took the leaders of your tribes—sage men, and recognized—and I set them leaders over you, rulers of thousands, and rulers of hundreds, and rulers of fifties, and rulers of tens, and scriveners for your tribes.

16 And I commanded your judges at that time, to say: ‘Hear between your brothers, and judge them righteously—between a man and between his brother, and between his sojourner.

16 And I commanded your judges at that time, to say: ‘Hear between your brothers, and judge them righteously—between a man and between his brother, and between his sojourner.

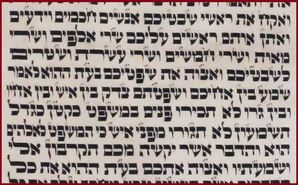

Neither the text from Numbers 11 nor the above passage reveals how Moses was supposed to know whom to take, except that they are “whom you know that they are elders of the people, and scriveners of them” (Numbers 11:16), and “sage men, and recognized” (Deuteronomy 1:15). There is a hint, however, in the term “scriveners,” the Hebrew of which—SHOTREI—is used in the beginning of the Exodus account in Exodus 5:14. In that verse is found men responsible for the other Hebrew slave’s work productivity, and who are beaten for not forcing them to meet the daily quota of bricks.

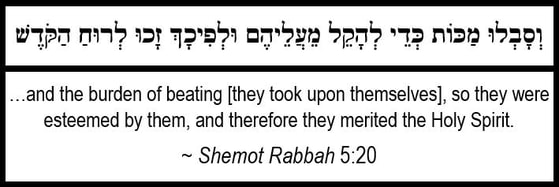

The text of Shemot Rabbah 5:20 provides an insightful reason why these particular men were “recognized” and viewed by the descriptor of “sage.”

The text of Shemot Rabbah 5:20 provides an insightful reason why these particular men were “recognized” and viewed by the descriptor of “sage.”

The historical viewpoint in Judaism is that those Hebrew scriveners in charge of the slave-labor’s brick production were willing to suffer the blows that should have been passed down to the slave-labor who were unable to maintain the workload. Their self-sacrificial nature merited them positions of honor at a later point. As they had proven able to lead the people in a righteous way when no honor was upon them, so they could be trusted to lead the people in a righteous way when great honor was entailed—and this they did with the presence of the Holy Spirit empowering their task. This is an important trait every leader should adopt.

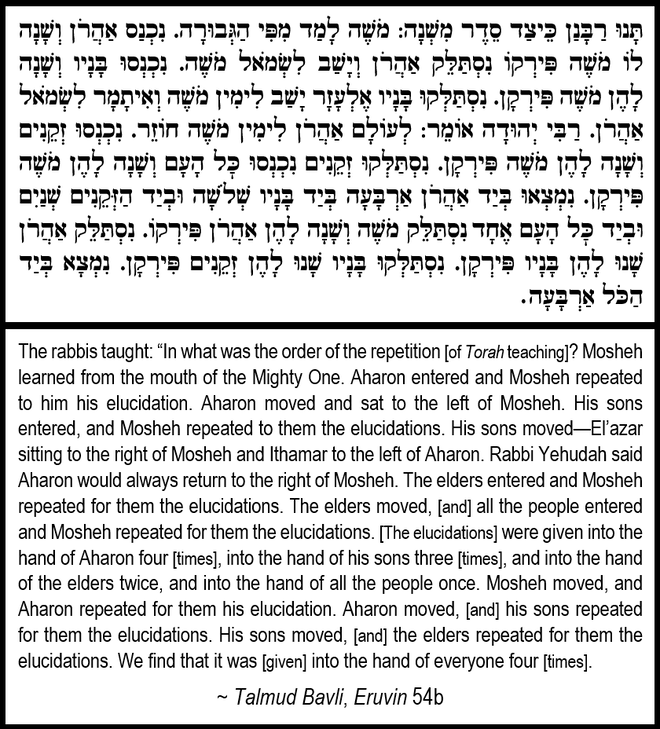

In order to exemplify that the teaching was singular and with one spiritual voice between all who were delegated to sit in judgment over Israel, a very rigid methodology was enacted to dispense it to everyone in the nation, as we see recorded in the Talmud Bavli, Eruvin 54b.

The successive explanation of the commands by the leaders of Israel reiterated its singular authority to the people, while simultaneously reinforcing the legitimacy of the appointed elders as valid sources of Divine information before all the nation. This delegated apportioning of judicial power meant that the nation could expect the same level of spiritual insight whether it came from Moses or from the seventy judges.

This arrangement of seventy-plus-one eventually developed into the standard model of judgment in Israel. It was known in Hebrew as the BEIT DIN “House of Judgment,” and then later, after Roman influence came upon the land of Israel, was popularly referred to as the SANHEDRIN “Seated Group,” based on the Greek term Synedrion.

This arrangement of seventy-plus-one eventually developed into the standard model of judgment in Israel. It was known in Hebrew as the BEIT DIN “House of Judgment,” and then later, after Roman influence came upon the land of Israel, was popularly referred to as the SANHEDRIN “Seated Group,” based on the Greek term Synedrion.

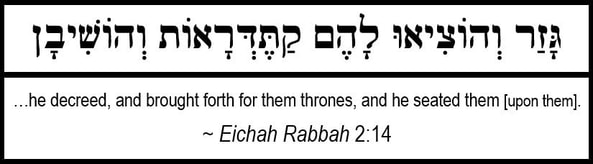

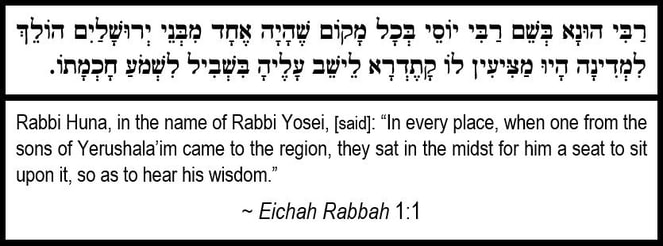

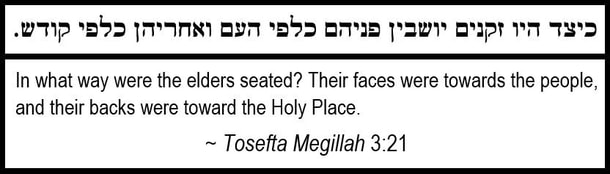

This Biblical form of judgment was recognized, and the occupants of the group were given honor for their high position, even being seated upon KATHEDRAOT “thrones”—a detail we find in the text of Eichah Rabbah 2:14.

Due to the high calling as they sit upon the “throne of Moses,” they are expected to enact all righteousness and proper interpretation of Torah performance in every area wherein the holy commands may reach and influence the life of the believer.

It is in this understanding that we can now return to the words of Yeshua in Matthew 23 and continue to examine their meaning with better contextual clarity.

It is in this understanding that we can now return to the words of Yeshua in Matthew 23 and continue to examine their meaning with better contextual clarity.

I have intentionally provided only the first half of Matthew 23:3 to focus on the significance of this statement. The second half will be addressed later.

Yeshua’s assertion is based on the Torah itself. National growth and Torah implementation meant new and unexpected circumstances requiring the discernment of sages to arbitrate righteousness. The Holy One prepared for that by commanding broad access to those authorities, as seen in Deuteronomy 16:18-20.

19 You shall not warp judgment, nor acknowledge faces, and neither take a gift, for the gift blinds [the] eyes of [the] sages, and perverts the words of the righteous ones.

20 Righteous righteousness you must pursue, so that you shall live and inherit the land which YHWH your Deity gives to you.

20 Righteous righteousness you must pursue, so that you shall live and inherit the land which YHWH your Deity gives to you.

As with those suggested by Jethro in Exodus 18, these appointees would also need to possess righteous traits. An important factor from the above verses is that the commissioning was not limited to being elders like those first ordained by Moses. If the individual was recognized as a legitimate Torah “sage,” they could potentially officiate. Spiritual truths must only be disseminated by spiritual men who lead by example and live them inasmuch is applicable.

These positions commanded to be appointed in “all your gates” means that the scattered communities in Israel were expected to possess sources of Torah learning and exposition in order for justice to always be near any possible situation of question. Local groups were referred to as a BEIT DIN HAKATAN “The Small House of Judgment.” They presided over the locals to ensure proper judgment in all matters was being done.

In the event a matter was beyond the discernment capabilities of a BEIT DIN HAKATAN, the matter in question was taken to the highest court in Jerusalem: the BEIT DIN HAGADOL “The High House of Judgment.” This is explicitly allowed for in Deuteronomy 17:8-13.

These positions commanded to be appointed in “all your gates” means that the scattered communities in Israel were expected to possess sources of Torah learning and exposition in order for justice to always be near any possible situation of question. Local groups were referred to as a BEIT DIN HAKATAN “The Small House of Judgment.” They presided over the locals to ensure proper judgment in all matters was being done.

In the event a matter was beyond the discernment capabilities of a BEIT DIN HAKATAN, the matter in question was taken to the highest court in Jerusalem: the BEIT DIN HAGADOL “The High House of Judgment.” This is explicitly allowed for in Deuteronomy 17:8-13.

8 For a matter extraordinary for you to judge—between blood and blood, between strife and strife, and between blow and blow—matters of dispute in your gates, then you stand up and ascend to the place which YHWH your Deity shall choose.

9 And you shall come to the priests, the Levi’im, and to the judge who is in those days, and inquire, and they shall tell you the matter of the judgment.

9 And you shall come to the priests, the Levi’im, and to the judge who is in those days, and inquire, and they shall tell you the matter of the judgment.

|

10 And you shall do concerning the mouth of the matter which they tell you from that place which YHWH shall choose, and you shall guard to do according to all which they instruct you.

11 Concerning the mouth of the Torah which they shall instruct you and concerning the judgment which they shall speak to you, you shall do. Do not turn aside from the word which they shall tell you—to the right or left. |

12 And the man who shall act arrogantly on account of not listening to the priest who stands to minister there [to] YHWH your Deity, or to the judge, then that very man shall die, and you shall consume the evil from Yisra’el.

13 And all the people shall hear, and they shall fear, and shall not be arrogant further.

13 And all the people shall hear, and they shall fear, and shall not be arrogant further.

The insight of the BEIT DIN HAGADOL into the Torah is held as the highest decree of judgment, and their edicts unquestionably followed upon threat of death. This is the identity of the “Sanhedrin” that is mentioned in the New Testament texts.

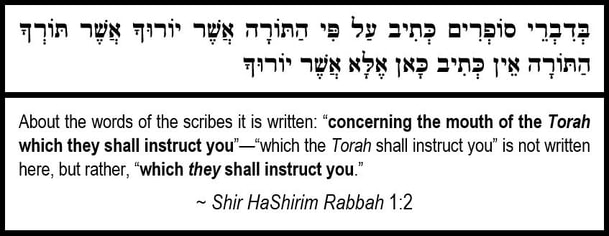

Consider the phrase in verse 11: AL PI HATORAH “concerning the mouth of the Torah.”

Consider the phrase in verse 11: AL PI HATORAH “concerning the mouth of the Torah.”

This is an idiom, for the Torah has no “mouth.” Since it is idiomatic language, how is its meaning understood? The concept is that the clear instructions of the Torah have embedded within them the necessary components to direct every course of action needed in implementing those commands. Each command has an obvious clearly stated meaning, which is called in Judaism TORAH SHEBICHTAV “Torah that is in writing.”

Beyond the Torah as it exists in its written performance, one can also ask the legitimate question: “What is Torah saying here?” “How is this command fulfilled in the full spectrum of its possible situational applications?” Whatever the implications derived from it--that is the “mouth of the Torah.” This is also called TORAH SHEBE’AL PEH “Torah that is in the mouth,” or in its more colloquial expression: “The Oral Torah.”

This concept of a TORAH SHEBE'AL PEH “Oral Torah” merits a brief detour in our main topic to illuminate it with a perspective not typically commented upon when the subject is discussed—yet can prove to be immensely helpful in assessing the concept in a fair and balanced manner.

Mere mention of the “Oral Torah” has traditionally been a point upon which Christian and secular scholars largely sneer and deride as unscriptural and untrustworthy. In fact, Western scholars have long viewed the veracity of oral transmission of information in cultures around the world as unreliable in contrast to the usually accepted content of written chronicles. The inherent flaw here is the ethnocentric notion that written information is indicative of a more advanced civilization than those transmitting information through an oral medium. This is, by definition, a position flawed from its outset.

The reality is that such a view has itself been proven to be generally ignorant of the truth of the astounding reliability of oral histories preserved in disparate cultures. The illuminating assessment by multi-disciplinary researchers into the field of spoken histories is that oral transmission is no less or more reliable than histories preserved through written accounts—as accurate historical transmission has been shown in Australian aboriginal tribes dating back over 400 generations [see: John Upton’s article “Ancient Sea Rise Tale Told Accurately for 10,000 Years,” in Scientific American, January 26th, 2015.], as well as North American oral transmission reliably accounting for events stretching back to the last glaciation period [see: Roger Echo-Hawk’s piece, “Ancient History in the New World: Integrating Oral Traditions and the Archaeological Record in Deep Time,” in American Antiquity, Vol. 65, No. 2, Cambridge University Press (2000).

A relatively recent example of the veracity of preserving information through oral transmission is shared here for the reader to truly appreciate the types of accurate details that can survive in this method of teaching.

On January 27th, 1700, the chronicles of the Genroku period (1688-1704) of Japan record that a tsunami six-hundred miles long struck the nation’s coast and resulted in significant destruction. It came with no warning of a preceding earthquake—a serious anomaly to the people of Japan who were already familiar with the reality that tsunamis generally followed felt earthquakes. Its origin remained a mystery until 1996, when, through the work of several seismologists and geologists, it was at last verified that at about 9 o’clock at night on January 26th, 1700, a magnitude-9.0 earthquake had struck the Pacific Northwest of the United States due to catastrophic tectonic activity from the Cascadia subduction zone and generated a tsunami of such power that over the next 10 hours it traversed the Pacific and was the source of the surprise tsunami experienced in Japan.

Incredibly, this event in the Pacific Northwest has survived in the oral histories of several tribes (the Huu-ay-aht First Nation peoples and Cowichan people of Vancouver Island, British Columbia, as well as the nearby Makah tribe of Neah Bay, Washington, the yet further Hoh and Quileute peoples of Washington, the Tillamook peoples of Oregon, and even the Tolowa and the Yurok peoples of the Klamath River area of northern California, over 400 miles southward). This event is referenced in the tale of the eradication of the first Anaqt people, or who were called the “Pachena Bay” peoples, by an earthquake of such violence that people could not even stand. These moments of tumult were followed by the waters of the Pacific shoreline speedily receding from their normal boundaries, only for the ocean to return in minutes surging unstoppably inland, destroying indigenous structures and lives with wave heights swelling over the tops of trees and leaving canoes to rest in the limbs overhead in the eventual residing of its waters—a detail retold by the Makah tribe. In those spoken histories is included such correct details as the season in which it occurred—remembered as winter—and the time of day that the earthquake hit--nighttime—as well as the tribal preservation of sufficiently reliable time-based information so as to arrive at the consensus that the devastating seismic shaking occurred likely in the Gregorian year of 1701—just one year of difference of the date of the actual physical event as recorded in the annals of Genroku Japan [see: Satake, K., Shimazaki, K., Tsuji, Y. et al. “Time and size of a giant earthquake in Cascadia inferred from Japanese tsunami records of January 1700.” Nature 379, (1996). See also: Katheryn Schulz’s “The Really Big One,” in The New Yorker, July 13th, 2015 online edition (July 20th print issue)].

This is a prime example of the ability for oral teaching to preserve truths that occurred in the distant past. It is also an exoneration of the method in which the Creator Himself repeatedly commanded Moses to initially present the Torah to the people of Israel—in over thirty (30) separate instances in the text of the Torah, the Creator commands Moses to “speak to the sons of Yisra’el” the various decrees and instructions that were later written down at an unknown date. For the time intervening between those spoken directives and them being committed to parchment, the Torah itself existed literally as an Oral Torah, and its trustworthiness is not a contested issue among believers. Based on this, one could conclude that to disparage the veracity of the Oral Torah is to similarly denigrate the reliability of the written Torah, as well. May we abandon such faithless positions and trust in the methods which the Creator has affirmed as legitimate for conveying truth to His people.

The reality is that such a view has itself been proven to be generally ignorant of the truth of the astounding reliability of oral histories preserved in disparate cultures. The illuminating assessment by multi-disciplinary researchers into the field of spoken histories is that oral transmission is no less or more reliable than histories preserved through written accounts—as accurate historical transmission has been shown in Australian aboriginal tribes dating back over 400 generations [see: John Upton’s article “Ancient Sea Rise Tale Told Accurately for 10,000 Years,” in Scientific American, January 26th, 2015.], as well as North American oral transmission reliably accounting for events stretching back to the last glaciation period [see: Roger Echo-Hawk’s piece, “Ancient History in the New World: Integrating Oral Traditions and the Archaeological Record in Deep Time,” in American Antiquity, Vol. 65, No. 2, Cambridge University Press (2000).

A relatively recent example of the veracity of preserving information through oral transmission is shared here for the reader to truly appreciate the types of accurate details that can survive in this method of teaching.

On January 27th, 1700, the chronicles of the Genroku period (1688-1704) of Japan record that a tsunami six-hundred miles long struck the nation’s coast and resulted in significant destruction. It came with no warning of a preceding earthquake—a serious anomaly to the people of Japan who were already familiar with the reality that tsunamis generally followed felt earthquakes. Its origin remained a mystery until 1996, when, through the work of several seismologists and geologists, it was at last verified that at about 9 o’clock at night on January 26th, 1700, a magnitude-9.0 earthquake had struck the Pacific Northwest of the United States due to catastrophic tectonic activity from the Cascadia subduction zone and generated a tsunami of such power that over the next 10 hours it traversed the Pacific and was the source of the surprise tsunami experienced in Japan.

Incredibly, this event in the Pacific Northwest has survived in the oral histories of several tribes (the Huu-ay-aht First Nation peoples and Cowichan people of Vancouver Island, British Columbia, as well as the nearby Makah tribe of Neah Bay, Washington, the yet further Hoh and Quileute peoples of Washington, the Tillamook peoples of Oregon, and even the Tolowa and the Yurok peoples of the Klamath River area of northern California, over 400 miles southward). This event is referenced in the tale of the eradication of the first Anaqt people, or who were called the “Pachena Bay” peoples, by an earthquake of such violence that people could not even stand. These moments of tumult were followed by the waters of the Pacific shoreline speedily receding from their normal boundaries, only for the ocean to return in minutes surging unstoppably inland, destroying indigenous structures and lives with wave heights swelling over the tops of trees and leaving canoes to rest in the limbs overhead in the eventual residing of its waters—a detail retold by the Makah tribe. In those spoken histories is included such correct details as the season in which it occurred—remembered as winter—and the time of day that the earthquake hit--nighttime—as well as the tribal preservation of sufficiently reliable time-based information so as to arrive at the consensus that the devastating seismic shaking occurred likely in the Gregorian year of 1701—just one year of difference of the date of the actual physical event as recorded in the annals of Genroku Japan [see: Satake, K., Shimazaki, K., Tsuji, Y. et al. “Time and size of a giant earthquake in Cascadia inferred from Japanese tsunami records of January 1700.” Nature 379, (1996). See also: Katheryn Schulz’s “The Really Big One,” in The New Yorker, July 13th, 2015 online edition (July 20th print issue)].

This is a prime example of the ability for oral teaching to preserve truths that occurred in the distant past. It is also an exoneration of the method in which the Creator Himself repeatedly commanded Moses to initially present the Torah to the people of Israel—in over thirty (30) separate instances in the text of the Torah, the Creator commands Moses to “speak to the sons of Yisra’el” the various decrees and instructions that were later written down at an unknown date. For the time intervening between those spoken directives and them being committed to parchment, the Torah itself existed literally as an Oral Torah, and its trustworthiness is not a contested issue among believers. Based on this, one could conclude that to disparage the veracity of the Oral Torah is to similarly denigrate the reliability of the written Torah, as well. May we abandon such faithless positions and trust in the methods which the Creator has affirmed as legitimate for conveying truth to His people.

While some may yet still scoff at the notion of an “Oral Torah,” the concept of TORAH SHEBE’AL PEH is repeatedly validated in Scripture. A prime example is in Yeshua’s teachings in Matthew 5, where He expounds upon the what Torah is really saying: 5:21-22 shows the prohibition against murder extends to feelings toward and mistreatment of those with whom we disagree. 5:27-28 shows the prohibition against adultery extends to lusting after married women. 5:31-32 shows the allowance for divorce is only valid within a specific context. 5:33-34 shows the deeper intent of the care we are to take in making vows. 5:38-41 shows the preferred way resolutions should be sought when one would inevitably come out on the losing end. 5:43-44 shows how we are to live the love we are called to give to our neighbors.

In each of these examples, Yeshua’s words assert a meaning not readily apparent in the plain written text of the Torah’s commands. None of His explanations are what a reader would reasonably conclude just by taking the statements of the Torah at face value. Rather, He is engaging in what Deuteronomy 17:11 called AL PI HATORAH “concerning the mouth of the Torah,” that is, He is affirming the validity of TORAH SHEBE’AL PEH “the Oral Torah.”

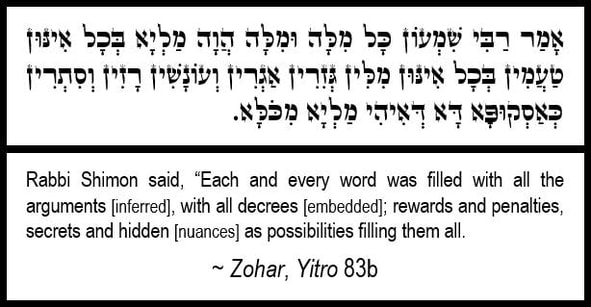

This spectrum of meaning and deeper implication in the words of Scripture validates the need for spiritual interpretation of the Word by sages who see beyond the surface level of the text and into the layered makeup of the Torah's polysemous Hebrew terms. An assertion in the text of the Zohar, Yitro 83b, explains this reality of the multifaceted nature of the Scriptural text.

This spectrum of meaning and deeper implication in the words of Scripture validates the need for spiritual interpretation of the Word by sages who see beyond the surface level of the text and into the layered makeup of the Torah's polysemous Hebrew terms. An assertion in the text of the Zohar, Yitro 83b, explains this reality of the multifaceted nature of the Scriptural text.

No one believer was expected to possess the spiritual insight to perceive all possible interpretations or inferences that are inherent in the text of the Torah. For this reason, the Creator graciously set up the ability for situations to be determined by bodies of sages whose wise perceptions would hopefully catch the subtle implications that might be a key determining factor when judging difficult situations.

This Torah allowance for further insight derived from the text itself applies to the community as a binding extrapolation giving a command’s fullest sense. The reason it is understood as binding is because the sages merely draw out the relevant meanings already existing in the Torah's words, but which are meanings obscured to some due to the individual potentially not realizing how to apply the spiritual information that is inherent in the words themselves. Their decrees in such situations are, in this respect, legitimately the words of the Torah, elucidated with careful exegesis of the Hebrew text for the rest of the community to clearly live out the Word.

Yeshua’s statement about obeying the sages therefore unquestionably upholds Deuteronomy 17:8-13, especially as He says “scribes” must be obeyed, being merely a modern synonym for the more archaic rendering of “scriveners” mentioned as appointed Torah authorities in Deuteronomy 16:18.

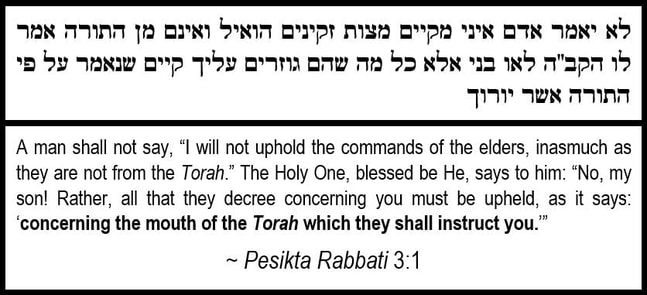

The text of Pesikta Rabbati 3:1 has an identical sentiment to Yeshua’s, quoting from Deuteronomy 17:11 to support its interpretation.

This Torah allowance for further insight derived from the text itself applies to the community as a binding extrapolation giving a command’s fullest sense. The reason it is understood as binding is because the sages merely draw out the relevant meanings already existing in the Torah's words, but which are meanings obscured to some due to the individual potentially not realizing how to apply the spiritual information that is inherent in the words themselves. Their decrees in such situations are, in this respect, legitimately the words of the Torah, elucidated with careful exegesis of the Hebrew text for the rest of the community to clearly live out the Word.

Yeshua’s statement about obeying the sages therefore unquestionably upholds Deuteronomy 17:8-13, especially as He says “scribes” must be obeyed, being merely a modern synonym for the more archaic rendering of “scriveners” mentioned as appointed Torah authorities in Deuteronomy 16:18.

The text of Pesikta Rabbati 3:1 has an identical sentiment to Yeshua’s, quoting from Deuteronomy 17:11 to support its interpretation.

At this point it is worth commenting on an interpretation of the first half of Matthew 23:3 that is popular in the Messianic and Hebrew Roots communities. Due to a detail preserved in a Medieval-era Hebrew translation of the book of Matthew, it has been advocated in relatively recent years by the Karaite Jewish author and teacher, Nehemiah Gordon.

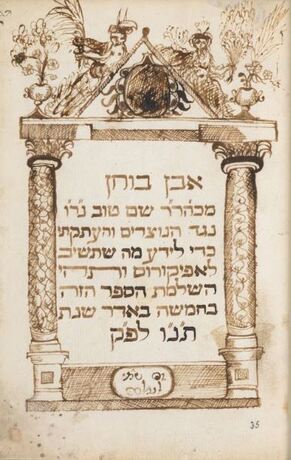

The detail Nehemiah Gordon promotes is preserved in the text of Evan Bochan, which is a Jewish polemical work against Christianity composed by Shem Tov ibn Yitzchak Shaprut.

The detail Nehemiah Gordon promotes is preserved in the text of Evan Bochan, which is a Jewish polemical work against Christianity composed by Shem Tov ibn Yitzchak Shaprut.

Shem Tov included a Hebrew version of the book of Matthew in his work that is unlike any other extant version. While a few Hebrew translations of Matthew date from the Middle Ages, Shem Tov’s version clearly used the Latin Vulgate as its foundation and included many bizarre readings. From a textual standpoint it is probably the poorest choice to promote as an authoritative version. As a translator who has studied its Hebrew text extensively, I would not personally advocate the Shem Tov Matthew as having any real value when it comes to the corpus of New Testament manuscripts, as it is unreliable in nature.

For whatever reason compelled Nehemiah Gordon to champion the text, his highlighting of a single term in it has brought attention to an understanding of Matthew 23:3 in clear opposition to the Torah’s command for the designation of teachers to explain it more fully.

His focus on Matthew 23:3 lay in a variant reading found in two manuscripts of Evan Bochan: Ms. Add. no. 26964, which is held in the British Library in London, and Ms. Opp. Add. 4· 72, held in the Bodleian Library at Oxford. The alternative reading contained in those two manuscripts is the word YOMAR, which Nehemiah Gordon reads as “he said,” and is in distinction to the other Shem Tov manuscripts, which read YOMRU “they shall say.”

For whatever reason compelled Nehemiah Gordon to champion the text, his highlighting of a single term in it has brought attention to an understanding of Matthew 23:3 in clear opposition to the Torah’s command for the designation of teachers to explain it more fully.

His focus on Matthew 23:3 lay in a variant reading found in two manuscripts of Evan Bochan: Ms. Add. no. 26964, which is held in the British Library in London, and Ms. Opp. Add. 4· 72, held in the Bodleian Library at Oxford. The alternative reading contained in those two manuscripts is the word YOMAR, which Nehemiah Gordon reads as “he said,” and is in distinction to the other Shem Tov manuscripts, which read YOMRU “they shall say.”

This refers to the dictate of Yeshua: “Every thing, therefore, that they shall say to you that you should guard, you must guard, and perform.” Nehemiah Gordon’s claim is that reading the term YOMAR as “he said” rather than “they shall say” is the preferred reading. He asserts YOMAR supports the notion that Yeshua refers only to Moses—that is, the Torah itself, and to keep only those commands as opposed to discernments relayed by the sages.

Gordon’s approach is problematic for two major reasons beyond its abrogation of the Torah command to appoint judges. First, the variant Hebrew term YOMAR in that manuscript, as shown below, is more accurately translated as “he shall say” rather than “he said.”

Gordon’s approach is problematic for two major reasons beyond its abrogation of the Torah command to appoint judges. First, the variant Hebrew term YOMAR in that manuscript, as shown below, is more accurately translated as “he shall say” rather than “he said.”

The clarification of its meaning essentially dissolves the point Gordon attempts to make with his “Moses / Torah” view of the term. The Hebrew should have been rendered as AMAR “he said” if it was to potentially convey the idea of Moses and the Torah as the sole authority.

Secondly, of the nine extant manuscripts of Shem Tov’s Evan Bochan, six possess the reading of YOMRU “they shall say.” One does not contain the passage at all. Only two manuscripts possess the variant of YOMAR “he shall say.” Of those two, Ms. Opp. Add. 4· 72 is a later copy of Ms. Add. no. 26964, with both even being incomplete versions of the book, ending abruptly at Matthew 23:22. This means just a single variant of YOMAR supports the idea that Yeshua said to listen to the rulings of the sages only when they taught the Torah as it is written.

In contrast to Nehemiah Gordon’s preference for the Shem Tov Hebrew Matthew 23:3 single variant reading, there is instead the older explanation of the Torah’s meaning of Deuteronomy 17:11 preserved in the text of Shir HaShirim Rabbah 1:2.

In contrast to Nehemiah Gordon’s preference for the Shem Tov Hebrew Matthew 23:3 single variant reading, there is instead the older explanation of the Torah’s meaning of Deuteronomy 17:11 preserved in the text of Shir HaShirim Rabbah 1:2.

This is the clarity obtained by adhering to the text’s grammatical construction: the passage explains how the nuanced wording of Deuteronomy 17:11 embeds in it a validation for following the exposition of the sages educated in the niceties of Torah. The Scripture is clear: the believer follows edicts made by sages elucidating how the Torah applies in all its facets.

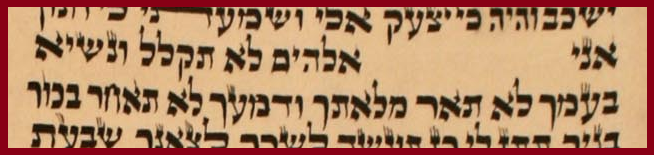

They operate by divine sanction; a custodial position of supernal placement whose edicts are obeyed. For this reason, the Torah also refers to them by a term carrying incredible weight. This is seen in the words of Exodus 21:6, Exodus 22:7-9, and Exodus 22:28, where I have left intact in each passage in transliterated phonetic form the Hebrew term of interest.

They operate by divine sanction; a custodial position of supernal placement whose edicts are obeyed. For this reason, the Torah also refers to them by a term carrying incredible weight. This is seen in the words of Exodus 21:6, Exodus 22:7-9, and Exodus 22:28, where I have left intact in each passage in transliterated phonetic form the Hebrew term of interest.

7 If a man gives to his fellow silver, or vessels to guard, and it is stolen from [the] house of the man, if the thief is found, he repays double.

9 Concerning every matter of guilt—concerning ox, concerning donkey, concerning sheep, concerning garment, concerning any [that is] lost, which [one] shall say such is his, unto ha’elohim is brought the matter of both; [he] whom elohim shall condemn shall repay double to his fellow.

~ Exodus 22:7-9

~ Exodus 22:7-9

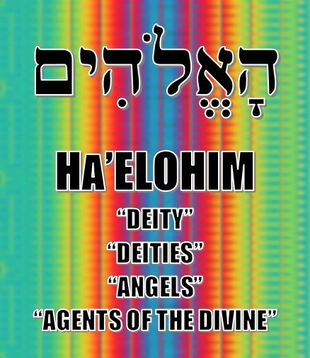

The Targums--Onkelos, Pseudo Yonatan, and Neofiti—and the Aramaic Peshitta for these passages steadily rendered the term ELOHIM with the word “judges” rather than “Deity.” This interpretation is logical given the broader context of the chapters: they address civil matters requiring litigation that are realized through trusted representatives of Divine authority.

Although the term ELOHIM is not literally defined as “judge,” the conceptual use is of a recognized agent for the Divine arbitrating righteous decrees as necessary.

Although the term ELOHIM is not literally defined as “judge,” the conceptual use is of a recognized agent for the Divine arbitrating righteous decrees as necessary.

These agents act within the boundaries of the Torah, so their rulings from careful application of the Hebrew in the Torah’s commandments must be accepted and followed.

This is seen in 1st Kings 22:8, where a question exists about the probability of victory in a battle for the kings of Israel and Judah. Their concern is laid upon a prophet named Micaiah.

This is seen in 1st Kings 22:8, where a question exists about the probability of victory in a battle for the kings of Israel and Judah. Their concern is laid upon a prophet named Micaiah.

The complete account is arguably one of the oddest in all of Scripture, but the point here is they knew they needed help beyond what the Torah itself could provide in its written form: although wars are allowed for in the Torah’s text, when to go to war is not specified, and so they had to LIDROSH ET YHWH “inquire of YHWH” to know the proper course of action.

The phrase links to the one mentioned earlier of those who came to Moses LIDROSH ELOHIM “to inquire of [the] Deity” for clarity on matters beyond their competency. It also connects to 2nd Kings 22, in the rediscovery of the Temple Torah scroll in the reign of King Josiah. Upon being read the scroll, the king commands a delegation to inquire of the Creator about what should be done. The group seeks out a prophetess--Huldah, as seen in 22:18.

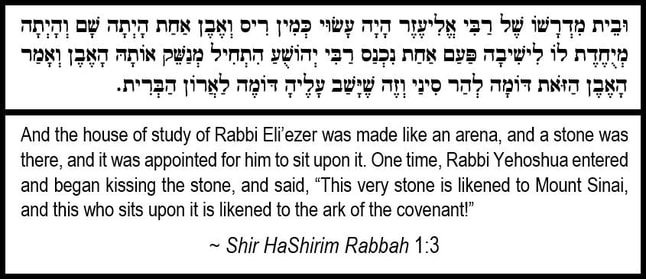

These examples reinforce that the sages elucidating the Torah’s relevance for everyday circumstances are to be viewed as human agents for the Divine. This esteem for them is expressed poignantly in the text of Shir HaShirim Rabbah 1:3.

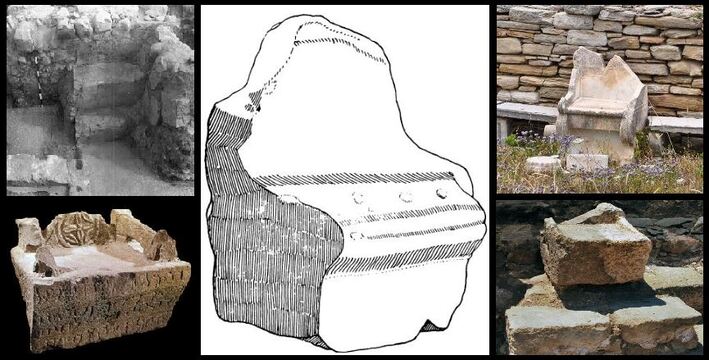

This mention of the seat upon which the sage sat being a “stone” is important also in verifying the archaeological finds in ancient synagogues, wherein repeated distinct stone chairs of varying elaborate design have been found in situ. Such seats have been discovered in Chorazin (of basalt), Chammath Tiberias (of white limestone--unfortunately now destroyed), En Gedi (of plastered stone), Chorvat Kur (of limestone) as well as in sites outside the land of Israel, like Dura-Europos (of plastered stone) in Syria, and Delos (of marble), on an island in Greece. All of these finds strongly support the textual evidences preserved in Jewish writings of a special seat—particularly the material that was said to be used for the “seat of Moses.”

The provision in this is for righteous sages to create a unity of Torah application. The recognition of this respected authority even in far-spread locales is mentioned in Eichah Rabbah 1:1.

The acknowledgment of the vetted spiritual background of the sage was realized by the use of a special seat—which the text again calls a KATHEDRA, differing only in pronunciation from the KATHIDRA of Pesikta d’Rav Kahana 1:7, quoted earlier in this study. This shows the tradition was widespread enough for congregations to possess a specially designated seat despite the fact that their rural locale meant attendance by a valid sage was a rare occasion.

Note also that the above text specifies the sage would sit on the special seat so the congregation could hear “his wisdom”—which is not the Torah as it is written, but rather his elucidation of it that revealed his skill in understanding its nuanced application.

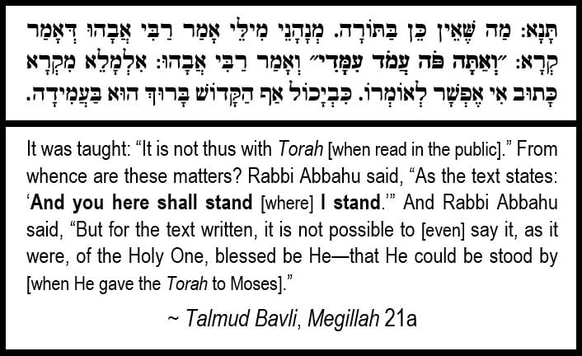

This distinction between what occurred when a sage sat upon the “seat of Moses” as opposed to reading from the Torah scroll is vital to grasp. The “seat of Moses” is for explanation of the Torah, but not for reading of the Torah itself. This is because public reading of the Torah was from antiquity done by one who stood.

This is explained in the Talmud Bavli, Megillah 21a, where discussion of the allowances for the public reading of the book of Esther revealed it can be read sitting or standing. The text then explains this is in contrast to the singular way in which the Torah is read in public.

Note also that the above text specifies the sage would sit on the special seat so the congregation could hear “his wisdom”—which is not the Torah as it is written, but rather his elucidation of it that revealed his skill in understanding its nuanced application.

This distinction between what occurred when a sage sat upon the “seat of Moses” as opposed to reading from the Torah scroll is vital to grasp. The “seat of Moses” is for explanation of the Torah, but not for reading of the Torah itself. This is because public reading of the Torah was from antiquity done by one who stood.

This is explained in the Talmud Bavli, Megillah 21a, where discussion of the allowances for the public reading of the book of Esther revealed it can be read sitting or standing. The text then explains this is in contrast to the singular way in which the Torah is read in public.

The basis for standing to read the Torah in public was gleaned from Deuteronomy 5:28, where Moses stood next to the Creator while He Himself stood and gave the Torah. Hence, Torah reading in a public area is done while standing, and exposition of it is done seated.

Incredibly, this closely aligns with the act we see recorded about Yeshua in Luke 4:16-22. Note carefully what information the text preserves about the incident.

Incredibly, this closely aligns with the act we see recorded about Yeshua in Luke 4:16-22. Note carefully what information the text preserves about the incident.

|

16 And he came to Natzrath, where he had been raised, and went, as that was his custom, to the assembly on the day of the Sabbath. And he stood to read,

17 and the scroll of Eshaya the prophet was given to him. And Yeshua opened the scroll and found the place where it is written: 18 “The Spirit of Marya is upon me, and on account of this, I am anointed to declare to the poor, and sent to heal the broken of heart, and to proclaim to the captives release, and to the unseeing, sight, and to strengthen the broken with release, 19 and to proclaim the acceptable year of Marya!” 20 And he rolled up the scroll, and gave it to the minister, and went [and] sat down. Yet, all who were in the assembly, their eyes were gazing at him. 21 Then he began to say to them, “Today is completed this Scripture that is in your ears.” 22 And they all witnessed him, and they marveled at the words of goodness that went forth from his mouth, and they were saying, “Is not this one the son of Yasef?” |

It does not say Yeshua read from the Torah, but from the Prophets--Isaiah 61:1-2. This was the haftarah portion—the passage closing the service from the books of the Prophets originally chosen to replace the weekly Torah passage due to thematic parallels. The precise origin of the practice is unconfirmed, but it is assumed it was implemented during the persecution against Torah reading by the Seleucid king, Antiochus IV Epiphanes. As the books of the Prophets were elevated to temporarily substitute for the Torah, the practice continued with similar honor—one stands to read the haftarah just like to read the Torah.

While reading Isaiah as a haftarah is common, notice in Luke 4:20 what happened after Yeshua finished His reading. It says He “sat down.” It is easy to assume this was the normal next move for one who finished their part in the service, but the text then states that the people were all gazing at Yeshua. Why would they be so focused on someone they had known since His childhood after He completed an act performed each Sabbath day? What is the reason for including this odd detail? The answer appears to lay within the statement that immediately precedes the mention of their attention on Him: that Yeshua “sat down.”

While reading Isaiah as a haftarah is common, notice in Luke 4:20 what happened after Yeshua finished His reading. It says He “sat down.” It is easy to assume this was the normal next move for one who finished their part in the service, but the text then states that the people were all gazing at Yeshua. Why would they be so focused on someone they had known since His childhood after He completed an act performed each Sabbath day? What is the reason for including this odd detail? The answer appears to lay within the statement that immediately precedes the mention of their attention on Him: that Yeshua “sat down.”

|

To be absolutely clear, the text does not elaborate where it was that He sat down after reading from the scroll of Isaiah. However, the fact that this action was thought to even be included in the account signals it has a meaning from which we can learn.

Can we possibly know if Yeshua took a seat with the rest of the congregants, or did He take His seat in the chair reserved for Torah sages—what the Aramaic text calls the “throne of Moses?” |

It seems like the latter is exactly what happened, for in the next verse--4:21, Yeshua began to explain what He just read. Knowing that the sages were expected to teach about the Scripture that had been read while being seated in the “seat of Moses” gives the information needed to view the passage from Luke 4:16-22 in a clearer manner. Additionally, it has been noted based on the position in which the several stone seats have been located in the ancient synagogues, that the special seats were all situated in such a manner that the entire congregation was facing the stone chair. The textual detail in Luke 4:20, of Yeshua sitting down and the eyes of all the congregation being upon Him, makes total sense that He sat down in that special and prominent chair reserved for Torah sages. This unique placement of the chair being set before the eyes of the whole congregation is the exact situation of the limestone seat preserved at Chammath Tiberius, whose back is against the wall facing Jerusalem. This detail also accords with the positioning of the seated elders that is preserved in the text of Tosefta Megillah 3:21.

In this way it aligns perfectly with the historical details of how public teaching occurred while also supporting the fact that Yeshua was Himself a rabbi—and the title of “rabbi” was only given to those recognized as sages heralding from the Pharisees—the very people who were later named in Matthew 23:2 as qualified to sit on the “throne of Moses” / “seat of Moses!” The actions and teaching of Yeshua aligned with the Torah and how its allowances developed into a progressive system of exposition on how it is to be performed.

|

3 …Yet, according to their performances, you shall not perform, for they say, and do not perform,

4 and they bind heavy burdens, and set them upon the shoulders of men, yet they, with their fingers, are not desiring that they should touch them! 5 And they perform all their performances that they be seen by the sons of men, and they make their tefillin wide and lengthen the blue cord of their robes. ~ Matthew 23:3-5 |

Yeshua provides a surprising turn of tone at this second half of verse 3, cautioning the people concerning the state of the Torah-sanctioned sages of His day: their behavior was a clear case of “do as I say, not as I do.” Although they sat upon an authoritative seat, their own traits were condemned in the judgments they were giving. This is sheer hypocrisy, and if it is unacceptable for believers—how more so is it of those who are esteemed as disseminating the commands into all possible facets of application?

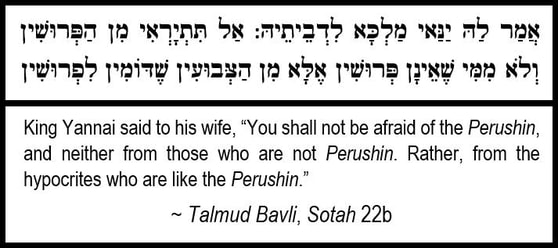

The Talmud Bavli, Sotah 22b, records the words of the Hasmonean King Yannai to his wife concerning these very types of hypocritical sages.

The Talmud Bavli, Sotah 22b, records the words of the Hasmonean King Yannai to his wife concerning these very types of hypocritical sages.

This warning is important in its alignment with what Yeshua said in Matthew 23:3—the need for cautious discernment was not for those of the Pharisaic party, nor of those outside the Pharisaic party, but rather, for those who were religious like the Pharisees, but engaged in blatant hypocrisy. They are a Pharisee in name only.

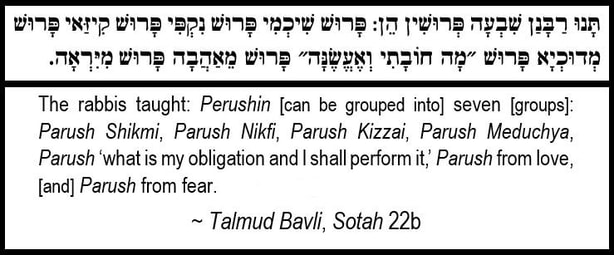

Interestingly, there is further Talmudic sentiment given towards the Pharisees as a whole that is highly critical, revealing that they had largely succumbed to the temptations that come with power and prestige, as we also see in the same passage as above.

Interestingly, there is further Talmudic sentiment given towards the Pharisees as a whole that is highly critical, revealing that they had largely succumbed to the temptations that come with power and prestige, as we also see in the same passage as above.

The term PARUSH is the Hebrew for “Pharisee,” and the four groups with transliterated Hebrew terms included are place-names serving to say something specific about the nature of that group, and are, for the purposes here, beyond our focus. What matters is that out of the seven, only the latter two are really commendable, and of them, only one (the Pharisee from love), is the praiseworthy type. To emphasize the fact that this Jewish view of those who largely inhabited the “seat of Moses” were by no means in the minority, this list is preserved also in the Talmud Yerushalmi, Berachot 9:5, and the text of Avot d’Rabbi Natan 37:4—with some variation between them, but the sense is maintained.

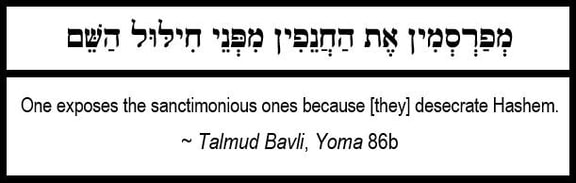

It is vital believers are warned about such individuals. While we must be careful in judging others, the behavior of leadership must be above reproach, for they represent the Holy One in guiding His people. To permit hypocrites in such positions cannot be allowed. Yeshua’s words in this chapter affirm that notion, as does the Talmud Bavli, in Yoma 86b.

The term Hashem means literally “The Name,” and is a title referring to the Creator Himself. We cannot permit His reputation to be damaged by hypocritical people in positions of religious power. To give them free reign to act impudently is destructive and opposite of the attributes seen in Scripture of how a true leader is to act. This is particularly confirmed when we consider the Hebrew “scriveners” who were the elders overseeing the rest of the slave-labor in Egypt, whom Torah and traditional historical chronicles explain were beaten so that those for whom they were responsible would not be harmed.

The majority of the leaders in the time of Yeshua were acting completely opposite—proclaiming oppressive edicts for the people to observe while sanctimoniously exempting themselves from them.

Interestingly, in the Talmud Yerushalmi, Sotah 3:4, it refers to actions seen as “destroying the world,” and among them it mentions MAKKAT PERUSHIN “plagues of the Pharisees.”

The majority of the leaders in the time of Yeshua were acting completely opposite—proclaiming oppressive edicts for the people to observe while sanctimoniously exempting themselves from them.

Interestingly, in the Talmud Yerushalmi, Sotah 3:4, it refers to actions seen as “destroying the world,” and among them it mentions MAKKAT PERUSHIN “plagues of the Pharisees.”

Yeshua hints at this "plague-like" behavior in His words recorded in Matthew 23:4 about how these sages “bind heavy burdens, and set them on the shoulders of men,” but do not bear them with the people. What He speaks of are the elucidations of the Torah—the AL PI HATORAH “concerning the mouth of the Torah” of Deuteronomy 17:11.

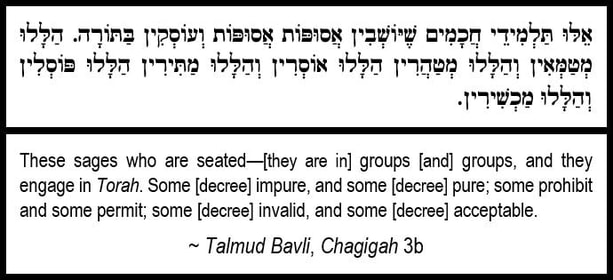

To be sure, their entire purpose is to make decrees as necessary, for so we read in the Talmud Bavli, Chagigah 3b.

To be sure, their entire purpose is to make decrees as necessary, for so we read in the Talmud Bavli, Chagigah 3b.

This important authority, however, could wreak havoc if abused, and that is exactly what happened as they prohibited and permitted without care for the situation of the people. Such disregard brought undue hardship to the populace and scorn upon themselves as they refused to hold themselves accountable to the same decrees.

This is not the way it was supposed to be. In contrast, Yeshua had previously spoken of His own style of Torah elucidation, as we see mentioned in Matthew 11:28-30.

This is not the way it was supposed to be. In contrast, Yeshua had previously spoken of His own style of Torah elucidation, as we see mentioned in Matthew 11:28-30.

28 You must come unto me, all you wearied and bearing burdens, and I shall relieve you.

30 for my yoke is sweet, and my burden is light.

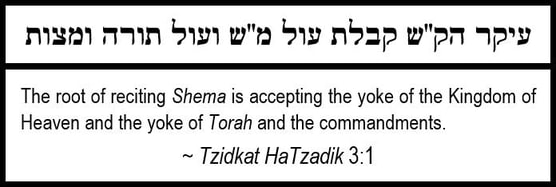

The burden of a “yoke” is idiomatic language in Judaism for agreeing to live in worship of the Holy One and obedience to His Torah, a concept we see stated clearly in the text of Tzidkat HaTzadik 3:1.

Yeshua’s words were in line with these concepts: the “burden” and “yoke” are His elucidations of the Torah, which is why He declares that we must be taught of Him—that is, to learn the more lenient rulings He promoted that did not oppress the sincere people desiring to live in accordance with the Torah.

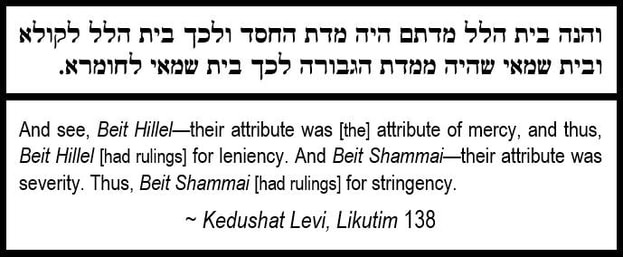

It is important to note that Yeshua’s declaration concerning His “sweet” and “light” manner of Torah application was in the context of His position as a recognized rabbi, and therefore, a Pharisee. Although it has been mentioned that seven “types” of Pharisees were recognized based on their behavior patterns, all of them stemmed from one of two actual schools of Torah application: Beit Hillel and Beit Shammai. The two were nearly identical in many ways, but in the aspects where they did disagree, the difference was obvious. The biggest difference between Beit Hillel and Beit Shammai, however, lay in the approach to the rulings they delivered to the people. The text of Kedushat Levi, Likutim 138 explains the key difference between the two Pharisaic schools.

It is important to note that Yeshua’s declaration concerning His “sweet” and “light” manner of Torah application was in the context of His position as a recognized rabbi, and therefore, a Pharisee. Although it has been mentioned that seven “types” of Pharisees were recognized based on their behavior patterns, all of them stemmed from one of two actual schools of Torah application: Beit Hillel and Beit Shammai. The two were nearly identical in many ways, but in the aspects where they did disagree, the difference was obvious. The biggest difference between Beit Hillel and Beit Shammai, however, lay in the approach to the rulings they delivered to the people. The text of Kedushat Levi, Likutim 138 explains the key difference between the two Pharisaic schools.

The sense of Yeshua’s words, therefore, is that He aligned with Beit Hillel in His “sweet” and “light” interpretation of how the Torah should be applied in its elucidations, and so His invectives against the Pharisees in Matthew 23 are largely aimed at the hypocrites and those of Beit Shammai, whose rulings were oppressive and sanctimonious due to their flagrant disregard for adhering to their own edicts.

This more lenient view of Beit Hillel can even be seen in the words of Gamaliel recorded in Acts 5:34-39, where the highly regarded Pharisee spoke saliently about the leniency that should be taken towards the growing proponents of Yeshua as the Messiah. Gamaliel was none other than the grandson of Hillel himself, who founded the Torah school of Beit Hillel. Gamaliel was also the teacher of Paul, as we see asserted in Acts 22:3, and although Paul engaged for a time in an incredibly stringent manner towards the early followers of Yeshua, he later returned to the lenient views of Hillel and espoused concepts easily in alignment with Beit Hillel’s approach to Torah rulings in the context of Gentiles who were entering into the faith through affirming Yeshua as the Messiah.

This more lenient view of Beit Hillel can even be seen in the words of Gamaliel recorded in Acts 5:34-39, where the highly regarded Pharisee spoke saliently about the leniency that should be taken towards the growing proponents of Yeshua as the Messiah. Gamaliel was none other than the grandson of Hillel himself, who founded the Torah school of Beit Hillel. Gamaliel was also the teacher of Paul, as we see asserted in Acts 22:3, and although Paul engaged for a time in an incredibly stringent manner towards the early followers of Yeshua, he later returned to the lenient views of Hillel and espoused concepts easily in alignment with Beit Hillel’s approach to Torah rulings in the context of Gentiles who were entering into the faith through affirming Yeshua as the Messiah.

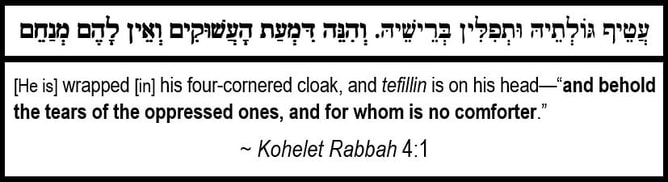

In contrast to Beit Hillel was those of Beit Shammai and all others in power who hypocritically held sway over the people, using their position as a means for self-glorification and control over those who did not know better. It is them of whom Yeshua lambasts in Matthew 23:5, when He calls them out for their self-aggrandizing actions, like broadening their tefillin and lengthening their tassels. This particular choice to begin the list of particular sins shows Yeshua was absolutely accepting the performance of tefillin (phylacteries in most English versions) and tassels, for the way He reprimands them is for how they are doing those commandments (not that they were doing them)—that is, He critiques their method that went outside the boundaries of AL PI HATORAH “concerning the mouth of the Torah.” The text of the Torah does not clearly designate the size of tefillin, nor does it give a proper length for tassels, yet Yeshua clearly rebukes the manner in which both are being performed by those sages. This can only mean that the size of the tefillin matters if someone is doing it to draw unnecessary attention to one’s self in a public setting, and likewise the length of the tassel matters for the same reason.

Incredibly, the text of Kohelet Rabbah 4:1, which quotes from Ecclesiastes 4:1, speaks precisely of those same types of individuals in a similarly critical voice.

Incredibly, the text of Kohelet Rabbah 4:1, which quotes from Ecclesiastes 4:1, speaks precisely of those same types of individuals in a similarly critical voice.

The sage is supposed to level the way forward for the believer, not make the way more difficult. Rulings must be for the promotion and flourishing of life, so that Torah performance takes root in the world and draws us all closer to the Kingdom mindset of sincere obedience. The throne of Moses must never be used to exclude His people or discourage them from drawing more and more of their lives under the canopy of the Creator’s good will.

Yeshua’s words as they fill the rest of Matthew 23 are some of the strongest He ever uttered, and yet He did so out of care for the people as a whole—both the simple folk as well as the sages who were leading in a profound and untenable disregard for the integrity their position demanded. He knew He would not be with them for long, so the impression He made had to be without question. Those who sit upon the “throne of Moses” should remember that although the term can be translated as such, it does not make them higher than the lowest of people for whom they advocate in their righteous rulings of the Torah. Rather, may all who symbolically sit in the “seat of Moses” take up the task of elucidating the Torah for the betterment of His people, and remember the words of Numbers 12:3.

Yeshua’s words as they fill the rest of Matthew 23 are some of the strongest He ever uttered, and yet He did so out of care for the people as a whole—both the simple folk as well as the sages who were leading in a profound and untenable disregard for the integrity their position demanded. He knew He would not be with them for long, so the impression He made had to be without question. Those who sit upon the “throne of Moses” should remember that although the term can be translated as such, it does not make them higher than the lowest of people for whom they advocate in their righteous rulings of the Torah. Rather, may all who symbolically sit in the “seat of Moses” take up the task of elucidating the Torah for the betterment of His people, and remember the words of Numbers 12:3.

He who first sat upon the throne of Moses did not use it to rule over the people, but to raise the people up to embrace the Word of the Holy One in its fullest measure.

May all who are seated thus be indistinguishable from him.

All study contents Copyright Jeremy Chance Springfield, except for graphics and images, which are Copyright their respective creators.