VERSES VERSUS VERSES

by Jeremy Chance Springfield

10/1/2022

This study is also available in audio.

The apostle Paul was a truly unique persona in first century Judea. His experience as a Roman citizen and a Jewish man gave him a direct perspective of the richness a life of faith can bring, while also seeing the decadence and depths of sin to which a deceived person could fall in a culture where righteousness is viewed as intolerance. Such a background was not so common for most of his fellow Jewish people, whose involvement with the celebrated decay that was Roman society was typically a cursory experience.

|

Paul’s letters preserve the witness of a man who was intense in his beliefs, and incredibly concerned for the edification and spiritual health of his fellow man. Although he touches on many salient topics throughout the content of his letters, a repeated theme is the call to be zealous for and well-versed in the Word.

|

This emphasis on an allegiance and familiarity with the text of Scripture likely came from his own experience as a Jewish youth uprooted out of the perversity of Roman society and transplanted in the spiritually rich soil of Jerusalem’s religious schools, as he emphasized occurred to him in Acts 22:3.

He asserts that although born in a Roman culture, he was brought up in the holy atmosphere of Jerusalem, and more so, near the feet of Gamaliel—one of Judaism’s most renowned spiritual authorities of the first century. By stating he was “right beside the feet of Gamali’el,” Paul is using a Jewish expression noting his exalted position as a student of the greatly revered rabbi, for the ancient religious schools would seat their pupils on cushions in rows before the teacher who sat higher on multiple cushions at the head of the room, with the brightest, most relevantly inquisitive among them placed on the front row, nearest their teacher. This is the meaning of Paul’s expression of his proximity to Gamaliel, which would have not only spoken volumes of his spiritual upbringing but would have also highlighted his expertise in the religious education he received.

In this environment the Word was poured over and examined in incredible detail, analyzed in every way in an attempt to glean from the eternal text applications that would enrich the lives of every believer. Verses of text were presented and discussed, and then linking or opposing verses were subsequently shared to bolster or refute in effort to arrive at as complete a view of the matter as possible. It is also relevant that the detail should be emphasized—the Word being taught was the Hebrew Scriptures—what is commonly but unfortunately called the “Old Testament.” It is known more respectfully by its Hebrew acronym of Tanakh: Torah, Nevi’im, and Ketuvim (Law, Prophets, and Writings)—composing the entirety of the Hebrew Scriptures. In these schools the Tanakh was the foundation for all learning.

In a later letter to the assembly at Galatia, Paul reiterates his austere devotion to and prodigy-like comprehension of his religious education, as recorded in Galatians 1:14.

Although in a setting of age-appropriate Jewish peers, Paul claims to have surpassed them in both comprehension and application of the traditional understandings of Judaism passed down from his forebears. These consistent declarations display a man whose commitment to the faith was unquestionable and his ability to assess and exegete the Word was profound.

Paul matured and after his revelation of Yeshua, went on to engage in staunch efforts to instill a love for that core reality of the Word among the assemblies he sought to edify. His many letters comprising so much of the New Testament highlight that endeavor to lay a proper groundwork of the Tanakh among the scattered congregations under his guidance.

His first recorded exhortation in this manner is powerfully expressed just a couple chapters prior in Acts 20:28-30.

His first recorded exhortation in this manner is powerfully expressed just a couple chapters prior in Acts 20:28-30.

|

28 You must be careful, therefore, with yourselves, and with the whole flock in which the Spirit of Holiness has appointed you overseers—that you shepherd the assembly of the Messiah, which he bought with his blood.

29 For I know that from after I leave, mighty wolves shall enter with you, who shall not be sparing unto the flock. 30 And also from you—of your own—shall strong men arise, speaking perversities, so as to turn away disciples to go after them. |

Throughout his letters, Paul’s insistence on the vital role the Scriptures play in a believer’s life is expressed time and again. In those recorded words is revealed his heart for the Creator’s people. He knew that a weak foundation in the Tanakh meant a believer who could be deceived when a false teacher brought opposition with their own perverse ideas.

This concern was by no means unfounded. His writings mention the battles he waged against false teachers who were intent on overturning the insightful Scriptural foundation that had been revealed to him which unified both Jew and Gentile into a harmonious community of faith. With the same zeal that he expressed as a youth for guarding his faith, he likewise fought back with all his ability against those who stood in opposition to the liberty he championed by the unification made possible through Yeshua’s righteousness. His fears were that those who opposed the revelations he had received and taught about the Tanakh would take away all the Messianic progress that had been made in the world. This was a duel for the hearts and minds of impressionable believers who had been taught truth, and then afterwards had that truth shaken with questionable teaching by misled promoters of faulty spiritual reasoning.

He presented a warning to the assembly in Colossae of this very concern, as recorded in Colossians 2:8.

He presented a warning to the assembly in Colossae of this very concern, as recorded in Colossians 2:8.

He knew well that a false teacher could do damage beyond imagination to an unprepared believer. Deceit is powerful and able to easily tear down what has been shakily built. Therefore, a proper construction of faith must occur in the life of each believer in order to withstand the lies that will inevitably come against our beliefs.

Even at the end of his life, Paul made certain that his faithful young protégé—Timothy—was likewise encouraged in this factor. The incarcerated elderly apostle’s young student had grown and matured, and at that point oversaw the lives of many believers who were dependent upon his correct learning and dissemination of the Hebrew Scriptures for the growth of their own faith.

Even at the end of his life, Paul made certain that his faithful young protégé—Timothy—was likewise encouraged in this factor. The incarcerated elderly apostle’s young student had grown and matured, and at that point oversaw the lives of many believers who were dependent upon his correct learning and dissemination of the Hebrew Scriptures for the growth of their own faith.

In his first letter to the young preacher, Paul wrote of the opposition to be expected, as recorded in 1st Timothy 4:1-2.

|

1 Yet, the Spirit clearly says that in the time of the end certain men shall depart from the belief, and they shall go after spirits of deception, and after teachings of destructive spirits!

2 These, who are in a character of falsehood, are deceptive, and speaking the lie, and are seared in their conscience… |

Truth versus falsehood was the situation facing those adhering to the Word. Without knowing the content of Scripture, deceivers would be able to wreak havoc on the faith of the weak. Timothy had to be prepared for this danger by being versed in the holy text.

It is in the second letter Paul wrote to Timothy that an extended focus on the importance of being founded in the Tanakh is shared with the young preacher. He begins by admonishing the Jewish youth concerning his own lineage of faithful believers, as seen in 2nd Timothy 3:14-15.

It is in the second letter Paul wrote to Timothy that an extended focus on the importance of being founded in the Tanakh is shared with the young preacher. He begins by admonishing the Jewish youth concerning his own lineage of faithful believers, as seen in 2nd Timothy 3:14-15.

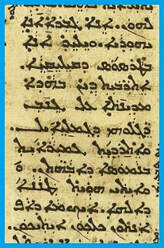

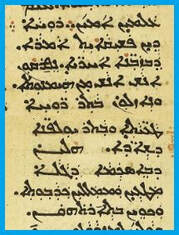

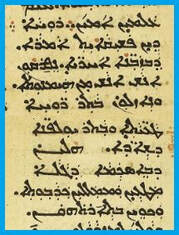

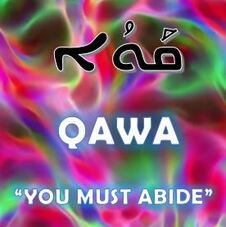

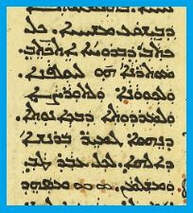

The word he uses for “you must abide” here in the Aramaic of the Peshitta New Testament is QAWA.

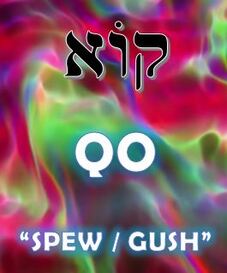

The Aramaic term serves as a translingual word-play, for its identical Hebrew spelling renders the word QO, which has the alternative meaning of “spew / gush.”

Not only was Timothy being called to abide in what he had been taught, he was also expected to proclaim it to others with a readiness to share, as we shall shortly see the passage goes on to clarify in 2nd Timothy 4.

The believer must understand he has nowhere else to go except to the Scriptures themselves for trustworthy doctrine. Without the surety of the Hebrew Scriptures, a believer is exposed to error and ultimately destruction. Paul emphasizes this by referencing that Timothy had, from his youth, been taught SEFRE QADISHE “the holy scrolls.”

It is likely that Paul saw in Timothy his own similar upbringing: a young man who existed in two worlds—the secular liberalness of Roman society and the lively holiness of Jewish culture. His own background had seen what the world had to offer, and so too Timothy’s mixed family would have placed him in somewhat similar of a situation, and the only source of light and hope in that upbringing would have been the purity of the Hebrew Scriptures.

Paul continues with this emphasis in 2nd Timothy 3:16-17.

Paul continues with this emphasis in 2nd Timothy 3:16-17.

The gravity of the situation facing Timothy is then expounded upon by the pen of Paul as he begins chapter 4 of his epistle. Having dealt firsthand with the present danger of false teachers and their teachings, he did his best to inculcate vigilance in the heart and mind of Timothy. This he did in the hopes that Timothy would be sufficiently equipped in the Tanakh to handle the hardships brought about by false teachers that would inevitably arise with his pastoral position.

2nd Timothy 4:1-4 presents the scenario set before the young man.

2nd Timothy 4:1-4 presents the scenario set before the young man.

|

1 I witness to you before Alaha, and our master Yeshua the Messiah, he who is prepared to judge the living and dead at the appearing of his Kingdom:

2 you must proclaim the Word, and you must be established in diligence, in time and out of time; you must reprove, and you must warn in all long-suffering of spirit and teaching. 3 For there shall be the time that wholesome teaching they shall not hear, but instead, according to their lusts, shall multiply unto their souls teachers in the enticing of their hearing, 4 and from the truth they shall turn their ears, yet to tales they shall turn! |

If the Tanakh is not held in the highest of regard, there is no hope for a solid foundation upon which a believer’s life can grow. Men are all too easily swayed by erroneous teachings, and so a commitment to the revealed text of Scripture and its practical and spiritual application had to be present in Timothy in order to righteously steer the assembly towards a fulfilling spiritual life. This factor had to be impressed upon the young man, for he would not always have the guidance of Paul to lead him through the troubled waters of faith, as we see is expressed in the words of 2nd Timothy 4:5-8.

|

5 Yet, you must be watchful in every thing, and you must endure the wrongs, and the work of a declarer you must perform, and you must complete your ministry,

6 for I, henceforth, I am to be poured out, and the time of dismissal has arrived. 7 I have contended a beautiful struggle, and my run is completed, and my trust I have kept, 8 and from now there is kept for me the crown of justice that shall be recompensed to me by my master in that Day, as he is the just judge--yet not for me only, but also for those who have loved his appearing. |

Paul’s situation was dire. This second address to Timothy occurred from the bitter confines of a Roman prison. From this incarceration Paul would know no freedom except the violent release of a gory death. He seems to have anticipated nothing less than an impending execution, but that dark future looming before him was brightened by the expectation of a glory to be bestowed by the one whose allegiance had been his since that fateful day on the road to Damascus. This imminent exit caused him to make a special request of his beloved disciple due to the loneliness he endured at the end of things.

2nd Timothy 4:9-12 details this request for a final goodbye and the background for his pitiable isolation.

|

9 Take care unto yourself that you come to me quickly,

10 for Dima did leave me, and loved this world, and went to Thesalaniqi; Qrisqas to Galatiya; Titas to Dalmatiya. 11 Luqa, he alone is with me. Marqas you must take, and bring with you, for he is suitable to me for the ministry. 12 Yet, Tukiqas I sent to Efesas. |

Luke alone remained to care for Paul as best he could, given the difficult situation the apostle endured. And yet, Paul desired to see Timothy (and Mark) again before he left the strong shackles of iron and the frail shackles of flesh.

This summons to his side ends with an order deserving of our careful attention. 2nd Timothy 4:13 has some interesting details concerning what Paul wanted Timothy to bring with him. In the popular traditional English of the King James Version, the Greek was translated like this:

This summons to his side ends with an order deserving of our careful attention. 2nd Timothy 4:13 has some interesting details concerning what Paul wanted Timothy to bring with him. In the popular traditional English of the King James Version, the Greek was translated like this:

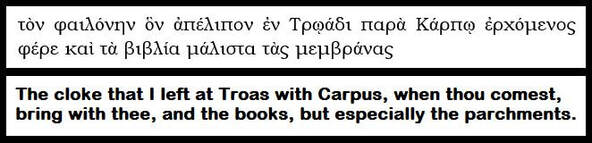

The Greek tells us that Paul requested three things to be brought to him when Timothy came:

These desired objects admittedly make some sense, when considered. Paul subsisted in meager form in a deplorable Roman prison, and so an extra garment would indeed be logical, especially in light of his later request in 4:21 that Timothy arrive “before winter.” The remainder of his request is also reasonable to think that there were texts of a dear status to him that he wanted to have access to again before his passing.

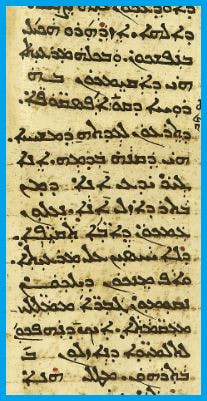

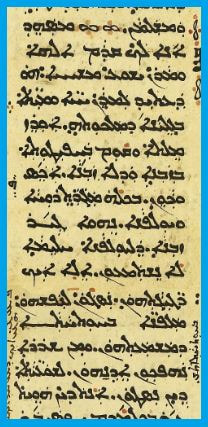

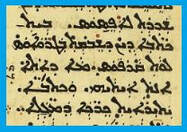

For as much as the Greek-based reading makes sense, however, the Aramaic text of 4:13, as preserved in the ancient Peshitta, provides an alternative reading that offers an even better sentiment than the traditional one, for it uniquely exemplifies Paul’s love for the Tanakh that had been present since his youth.

Based on the translation of the Semitic text, there is a glaring initial difference in what Paul desired Timothy bring him than what is recorded in the Greek. The Greek text uses the term PHAILONEN “cloak.” To say it is a rarely used term is an understatement: it appears only this once in the entirety of the Greek manuscripts of the New Testament, except for a minor spelling variant of PHELONEN in another manuscript of this exact same text.

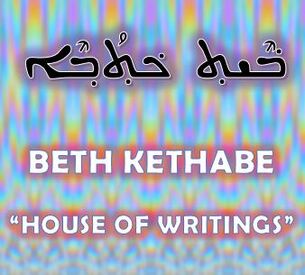

In a moment of incredible divergence, the Aramaic reading in this passage is BETH KETHABE “house of writings.” This is as literal of a translation as can be presented, and I rendered it this way out of respect for the text, but the word BETH is often used idiomatically to refer to a “case” or “receptacle” for something. The word is popularly encountered in such a manner regarding the “boxes” of tefillin, in which are housed tiny scrolls of Scripture from the Torah. In that usage, the cases are referred to in the singular in Hebrew as BAYIT and in the plural as BATIM. They are not literally “houses,” but “cases” that house the scrolls inside.

In this sense, it would be correct to render the Aramaic phrase here in 4:13 more idiomatically as “case of writings.” This would make the most sense of what the Aramaic is conveying—that Timothy bring to Paul a container of writings.

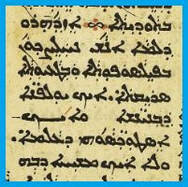

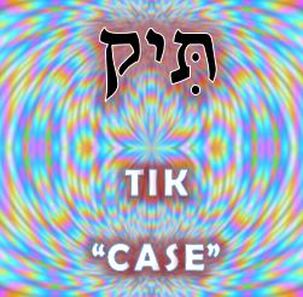

Not so surprisingly, Judaism has in its history the tradition to keep a scroll of Torah inside just such a container! The Hebrew term for this is most often called a TIK / TIKIM (pronounced teek / teekeem), meaning "case / cases."

Not so surprisingly, Judaism has in its history the tradition to keep a scroll of Torah inside just such a container! The Hebrew term for this is most often called a TIK / TIKIM (pronounced teek / teekeem), meaning "case / cases."

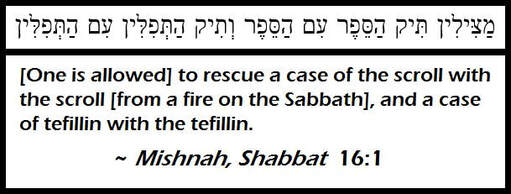

Safely storing an important religious article like a scroll of the Torah—or even tefillin, in a TIK is an ancient method mentioned first in the text of the Mishnah.

It would be reasonable for Paul to have used the Aramaic equivalent of the concept when one considers the rest of his request, rather than to assume he was asking for merely a cloak that could otherwise be obtained from almost anyone at his own location—especially since he admitted in 4:11 that Luke himself was already there with him, and in his profession as a physician, he could easily provide such a garment for Paul. What would not be so easily obtainable in a Roman city far from Israel would be a scroll of the Torah with its necessary protective case. However, it would be totally logical to request a Torah scroll from a Jewish man who was himself a trusted religious teacher in his own right who used those scrolls for his ministry.

The accompanying image shows traditional containers (BETH KETHABE / TIK) used for transporting scrolls of Torah. While many communities now house their scrolls in a stationary cabinet-like container in the synagogue known as an ARON KODESH "holy ark," or TEIVAH "container," the most ancient religious communities, like the Mizrachi Jews and the Romaniote Jews, still use a TIK to store the Torah to this day.

The accompanying image shows traditional containers (BETH KETHABE / TIK) used for transporting scrolls of Torah. While many communities now house their scrolls in a stationary cabinet-like container in the synagogue known as an ARON KODESH "holy ark," or TEIVAH "container," the most ancient religious communities, like the Mizrachi Jews and the Romaniote Jews, still use a TIK to store the Torah to this day.

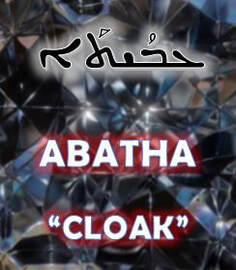

How, then, did the Greek reading arise that is so very different than the Aramaic? The question has no conclusive answer that has survived, but one can make a very good assumption based on linguistics and the matter of translation. The word ABATHA in Aramaic just happens to have the meaning of “cloak.”

The term is almost identical in the Aramaic to the word that does appear in the Peshitta’s text: BETH. In fact, just a few verses later in 4:19, the word “house” appears yet again when referencing the “house of Onesiphorus.” It is there spelled in the emphatic form of BATHA “the house.”

The reader can see in a comparison between the two that there is really only one letter difference between the word ABATHA “cloak” and BATHA “the house.” It would not take much error on the part of a translator to misread the term as “cloak” rather than “house.” If so, the Aramaic could easily be interpreted to be misread as: “Yet, the cloak I wrote that I left in Trawas…” This would explain away so easily the presence of the Greek reading of PHAILONEN “cloak.” The more likely reading as seen in the Aramaic, therefore, is that Paul was requesting Timothy bring him a TIK, a container that held a scroll of the Torah.

Continuing on now in that same passage of 4:13, the Aramaic reveals that it has preserved a continuity of thought from the beginning of what Paul wrote in this verse to the end. Look again at the verse as it is rendered from the Peshitta.

Continuing on now in that same passage of 4:13, the Aramaic reveals that it has preserved a continuity of thought from the beginning of what Paul wrote in this verse to the end. Look again at the verse as it is rendered from the Peshitta.

Yet, the house-of-writings that I left in Trawas with Qarpas--when that you come, you must bring, and the Writings--especially the rolls of the parchments!

The second item requested of Paul are the “Writings.” This is the word KETHABE in the Aramaic tongue. While it is the same term as used in the phrase BETH KETHABE, which refers to the TIK "case" in which a Torah scroll is traditionally kept, it is not meant in the same sense. Presented alone, the word KETHABE is usually utilized in the New Testament as a reference to the Hebrew Scriptures in general. However, since the Torah itself has just been referenced with the phrase BETH KETHABE, this usage of the word in isolation points to something else—the section of the Tanakh referred to as KETUVIM in the Hebrew tongue! In fact, KETHABE is merely the Aramaic cognate of the Hebrew KETUVIM!

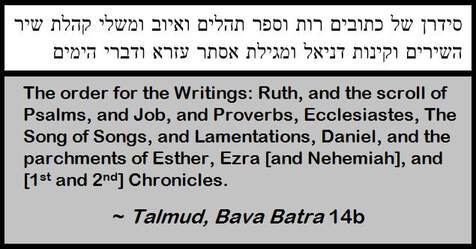

With this understanding, we can then presume that Paul meant the KETUVIM “Writings” when he used the word KETHABE in distinction to his usage of BETH KETHABE. The KETUVIM are made up of several books of the Tanakh. This portion of the Hebrew canon consists of the books listed in the Talmud Bavli, Bava Batra 14b.

The final part of what Paul requested was connected to the second. After he asks for the Writings, he says “especially the rolls of the parchments!” This distinguishing of particular “rolls of the parchments” is worded in such a way in the Aramaic that Timothy would have known precisely what texts his teacher was referencing.

The way this is worded in the Aramaic reveals what Paul was emphasizing.

The way this is worded in the Aramaic reveals what Paul was emphasizing.

Among the KETUVIM which Paul desired be brought, he especially wished that a certain and specific group of scrolls come with Timothy—the MEGALE. This word is the Aramaic cognate of the Hebrew MEGILLOT.

This term refers to a specific section of the books of the KETUVIM, comprising the scrolls of The Song of Songs, Ruth, Lamentations, Ecclesiastes, and Esther!

Why is this so important to spend time and effort on in addressing considering the topic of this study? The value in perceiving these clarifications from the Aramaic shows us that even at the end of his life, the central importance of the Tanakh remained in Paul’s faith. As his days on earth dwindled, he sought a final solace in the verses of the Hebrew Scriptures—the Law and the section of the Writings—most prominently, the five books of the Megillot.

The reason for those to be emphasized out of all the others likely lay in the nature of their content—the first and the last books of the Megillot particularly so.

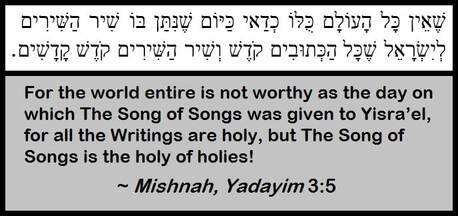

The Song of Songs is a beautiful text composed at the height of King Solomon’s spiritual insight, portraying the intimacy of the love between husband and wife, intended as a symbolic commentary on the love between the Creator and His people. For Paul to have indicated that he especially desired the Megillot be brought likely underscores the value placed upon those texts in Judaism—a value particularly highlighted in the sentiment of Rabbi Akiva, who lived in the latter part of the generation of Paul, and who is recorded in the Mishnah, Yadayim 3:5, to have made a statement showcasing the high regard of the foremost of those texts.

Why is this so important to spend time and effort on in addressing considering the topic of this study? The value in perceiving these clarifications from the Aramaic shows us that even at the end of his life, the central importance of the Tanakh remained in Paul’s faith. As his days on earth dwindled, he sought a final solace in the verses of the Hebrew Scriptures—the Law and the section of the Writings—most prominently, the five books of the Megillot.

The reason for those to be emphasized out of all the others likely lay in the nature of their content—the first and the last books of the Megillot particularly so.

The Song of Songs is a beautiful text composed at the height of King Solomon’s spiritual insight, portraying the intimacy of the love between husband and wife, intended as a symbolic commentary on the love between the Creator and His people. For Paul to have indicated that he especially desired the Megillot be brought likely underscores the value placed upon those texts in Judaism—a value particularly highlighted in the sentiment of Rabbi Akiva, who lived in the latter part of the generation of Paul, and who is recorded in the Mishnah, Yadayim 3:5, to have made a statement showcasing the high regard of the foremost of those texts.

Such an intimate text as The Song of Songs would make sense as a desirable thing when Paul is preparing himself to draw even closer to his Maker at his death.

Similarly, the book of Ruth, which details the joining of an outsider to Israel, would also make sense in light of Paul’s situation: an outsider due to his affirmation of Yeshua as the Messiah, he would yet be joined to his people and his Deity in death in a manner he did not enjoy in life.

The content of the book of Lamentations chronicles the mourning of the prophet Jeremiah over the loss of the Temple, and Paul knew that in just a few years after his own passing, the prophetic words of Yeshua concerning the security of the Temple would be realized and it would be lost to his people for an undetermined amount of time.

The book of Ecclesiastes would likewise be a well-placed reminder that this earthly life was insignificant in comparison to the true purpose of man: to fear the Creator and keep His commandments, which is what Paul had sought to do all of his life.

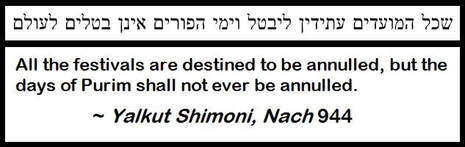

The final book of the Megillot--Esther—also surely held special significance to Paul, for it recorded the astounding deeds of his direct ancestors from the tribe of Benjamin and displayed their faith in the face of the threat of death. Perhaps he even took some comfort in that text as he likely viewed it from the perspective of the teachers from his youth, who assert of its festival of Purim a surprising concept, as recorded in the ancient rabbinic text of Yalkut Shimoni to Nach 944.

Similarly, the book of Ruth, which details the joining of an outsider to Israel, would also make sense in light of Paul’s situation: an outsider due to his affirmation of Yeshua as the Messiah, he would yet be joined to his people and his Deity in death in a manner he did not enjoy in life.

The content of the book of Lamentations chronicles the mourning of the prophet Jeremiah over the loss of the Temple, and Paul knew that in just a few years after his own passing, the prophetic words of Yeshua concerning the security of the Temple would be realized and it would be lost to his people for an undetermined amount of time.

The book of Ecclesiastes would likewise be a well-placed reminder that this earthly life was insignificant in comparison to the true purpose of man: to fear the Creator and keep His commandments, which is what Paul had sought to do all of his life.

The final book of the Megillot--Esther—also surely held special significance to Paul, for it recorded the astounding deeds of his direct ancestors from the tribe of Benjamin and displayed their faith in the face of the threat of death. Perhaps he even took some comfort in that text as he likely viewed it from the perspective of the teachers from his youth, who assert of its festival of Purim a surprising concept, as recorded in the ancient rabbinic text of Yalkut Shimoni to Nach 944.

Understanding the content and context of these five books of the Megillot / Megale, it makes total sense why Paul specified they especially be brought to him when Timothy came. The nature of their content would have immediately connected with his mortal circumstances.

At the end of his days, Paul maintained that cherished view of the Tanakh which had carried him through a life of so many surprises, both the good and the bad. Although he had known blessing and hardship, he had also seen what the Word established in the heart of a believer could accomplish. False teachers had challenged his work and sought to overturn the foundations he had laid for the Kingdom, and his steadfast adherence to Scripture had allowed him to confront their errors and show the eternal realities of the Spirit contained in those holy texts.

It was truth versus falsehood.

Life versus death.

The Word versus vain philosophy.

Verses versus verses.

Every believer will likewise face similar theological duels with false teachers at some point in the walk of faith, and must be prepared to offer a rebuttal based in truth to the deception that will inevitably confront their faith.

At the end of his days, Paul maintained that cherished view of the Tanakh which had carried him through a life of so many surprises, both the good and the bad. Although he had known blessing and hardship, he had also seen what the Word established in the heart of a believer could accomplish. False teachers had challenged his work and sought to overturn the foundations he had laid for the Kingdom, and his steadfast adherence to Scripture had allowed him to confront their errors and show the eternal realities of the Spirit contained in those holy texts.

It was truth versus falsehood.

Life versus death.

The Word versus vain philosophy.

Verses versus verses.

Every believer will likewise face similar theological duels with false teachers at some point in the walk of faith, and must be prepared to offer a rebuttal based in truth to the deception that will inevitably confront their faith.

These truths Paul did his best to convey, imparting the same zeal he had known from childhood to every believer in his reach of influence. Timothy was the last recorded recipient of this zealous focus on the text of Scripture, and from his youthful protégé, Paul sought one last moment of solace from the Tanakh that had been a faithful source of truth in his own life. Even at the end of all things, Paul’s attention on the Creator’s Word never failed.

The preeminence of that Word must be as much of a reality in our life today as Paul urged it to be among Yeshua’s early followers.

The preeminence of that Word must be as much of a reality in our life today as Paul urged it to be among Yeshua’s early followers.

All study contents Copyright Jeremy Chance Springfield, except for graphics and images, which are Copyright their respective creators.