FEW THE CHOSEN

by Jeremy Chance Springfield

10/12/19

The parables preserved in the teaching of Yeshua are relatable, succinct methods to reveal divine truths to a populace who might not otherwise be so fluent in such specific topics. Much of the audience who heard the traveling Messiah were not always highly educated in rabbinic schools of the day, especially in the wilder frontiers of northern Galilee, where much of His ministry was focused. However, these people still had a living faith that desired to connect with the Holy One. And so, rather than dismiss these people of the land entirely as unworthy candidates for eternal truths, Yeshua embraced the situation and utilized a teaching method that was able to speak to the mundane experiences His hearers would be able to appreciate and build upon.

The parables thus touch on sundry concepts, and in this multi-faceted presentation, are able to deliver all manner of important spiritual details in unexpected ways. Rather than the very austere setting of rabbinic institutional learning encountered in Judea, the parables could be presented to an audience whose Scriptural backgrounds would have ranged from that of neophytes to seasoned disciples. Mindful of this scope, Yeshua’s parables utilized simplicity and ingenuity to convey the Father’s heart for people all across the spectrum of the true faith.

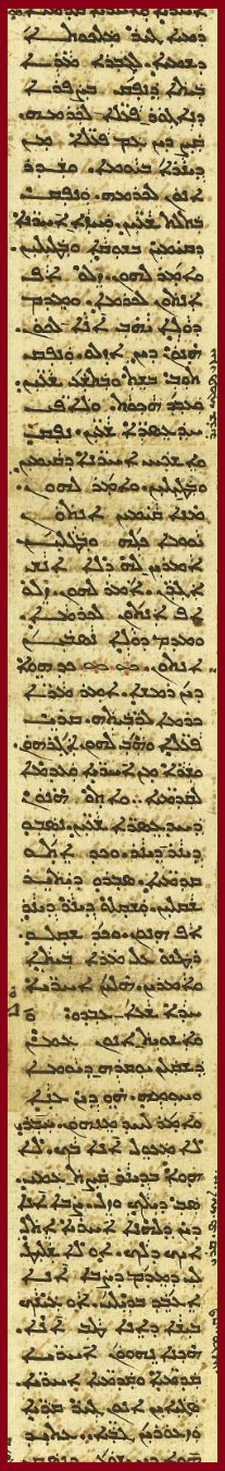

Over the millennia His parables have been explored and sounded by believers for their unique merits and applications in the faith-based life. Many important views and details have been gleaned in this attention. However, one area that has not received as much attention as it really should is that of looking at the parables as they have been preserved in their Semitic grammatical nature. While some might be quick to groan at the mention of grammar and word usage, such aspects are actually important to the Biblical writers, and are used to convey important details with their own spiritual applications. Noting the Semitic nuances of word choice is thus able to provide a richness and clarity to the teachings of the Messiah that is simply not able to be arrived at in any other way.

The parables thus touch on sundry concepts, and in this multi-faceted presentation, are able to deliver all manner of important spiritual details in unexpected ways. Rather than the very austere setting of rabbinic institutional learning encountered in Judea, the parables could be presented to an audience whose Scriptural backgrounds would have ranged from that of neophytes to seasoned disciples. Mindful of this scope, Yeshua’s parables utilized simplicity and ingenuity to convey the Father’s heart for people all across the spectrum of the true faith.

Over the millennia His parables have been explored and sounded by believers for their unique merits and applications in the faith-based life. Many important views and details have been gleaned in this attention. However, one area that has not received as much attention as it really should is that of looking at the parables as they have been preserved in their Semitic grammatical nature. While some might be quick to groan at the mention of grammar and word usage, such aspects are actually important to the Biblical writers, and are used to convey important details with their own spiritual applications. Noting the Semitic nuances of word choice is thus able to provide a richness and clarity to the teachings of the Messiah that is simply not able to be arrived at in any other way.

This study, therefore, will focus on just one example of such significance for the reader to appreciate how Yeshua used parables and the language of the land of Israel to speak to His listeners and bring important spiritual connections to their mind. Let us turn to the text of Matthew 20:1-15 as it is preserved for us in the Aramaic text of the Eastern Peshitta. In this ancient Semitic text we will find upon closer examination of the parable a creative presentation that Yeshua wrought whereby His listeners would be able to learn more than we are able to realize through Greek texts or the well-meaning veil of modern translations.

1 “For the Kingdom of the Heavens is likened to a man – the master of the house – who went out at dawn to hire laborers for his vineyard.

2 Yet, he agreed with the laborers for a denarius at a day and sent them to the vineyard.

3 And he went out in three hours, and saw others who were standing in the market, and were idle.

4 And he said to them, ‘You must go also to the vineyard, and the thing that is fitting I shall give to you.’

5 And those went. And he went out again in the sixth and in the ninth hours and did likewise.

6 And right at eleven hours he went out and found others who were standing, and were idle, and he said to them, ‘Why are you standing the entire day idle?’

7 They said to him, ‘No man hired us.’ He said to them, ‘You must go also to the vineyard, and the thing that is fitting you shall receive!’

8 Yet, when it was evening, the master of the vineyard said to the steward, ‘You must call the laborers and you must give them their payments. And begin from the last and unto the first.’

9 And they came, those of the eleventh hour; they took a denarius apiece.

10 And when came the first, they supposed that greater they should receive, and they received a denarius apiece also!

11 And when they received, they murmured against the master of the house,

12 and they said, ‘These last one hour have done, and you made them worthy with us, who bore the weight of the day and its heat!’

13 Yet, he replied, and said to one from them, ‘My friend, I am not unjust with you. Did you not on a denarius agree with me?

14 You must take your own, and you must go. Yet, I desire that to these last I shall give as that I did to you.

15 Or is it not permitted me that the thing that I desire, I shall do with my own? Or is your eye evil that I am good?’

16 Thus, the last shall be the first, and the first the last; for many are those called, and few the chosen.”

2 Yet, he agreed with the laborers for a denarius at a day and sent them to the vineyard.

3 And he went out in three hours, and saw others who were standing in the market, and were idle.

4 And he said to them, ‘You must go also to the vineyard, and the thing that is fitting I shall give to you.’

5 And those went. And he went out again in the sixth and in the ninth hours and did likewise.

6 And right at eleven hours he went out and found others who were standing, and were idle, and he said to them, ‘Why are you standing the entire day idle?’

7 They said to him, ‘No man hired us.’ He said to them, ‘You must go also to the vineyard, and the thing that is fitting you shall receive!’

8 Yet, when it was evening, the master of the vineyard said to the steward, ‘You must call the laborers and you must give them their payments. And begin from the last and unto the first.’

9 And they came, those of the eleventh hour; they took a denarius apiece.

10 And when came the first, they supposed that greater they should receive, and they received a denarius apiece also!

11 And when they received, they murmured against the master of the house,

12 and they said, ‘These last one hour have done, and you made them worthy with us, who bore the weight of the day and its heat!’

13 Yet, he replied, and said to one from them, ‘My friend, I am not unjust with you. Did you not on a denarius agree with me?

14 You must take your own, and you must go. Yet, I desire that to these last I shall give as that I did to you.

15 Or is it not permitted me that the thing that I desire, I shall do with my own? Or is your eye evil that I am good?’

16 Thus, the last shall be the first, and the first the last; for many are those called, and few the chosen.”

This parable is quite direct in the presentation and content. While some of Yeshua’s parables can be more complex in regard to intent, this particular one is simplistic and provides an excellent example for us. It is straightforward, and yet, the Aramaic text behind it gives the student of Scripture a more in-depth reading whereby it can be appreciated. Let us observe now how the Aramaic adds to the content of the parable.

To begin with, the setting of this parable is worth taking note. It is all about workers chosen to labor in a vineyard. Grapes cultivated and grown are ready to harvest, and the vineyard’s owner is in pressing need of laborers to reap the bounty from the vines. Understanding the Biblical and Jewish usage of a vineyard is thus significant for us to appreciate all that the parable conveys. While vineyards are mentioned in scattered references in the Hebrew Scriptures, of particular importance is the context of the vineyard in the book of Isaiah. In chapters 1, 3, and 5, the prophet prominently features a vineyard in his prophecies and directly links it to the Hebrew people and nation. The vineyard produces abundant fruit that needs reaping so others may benefit from its goodness. Yeshua uses this concept to form the basis for the parable. This is all about laboring for what belongs to the Holy One. As a people, Israel has a purpose in this world – to bear and to bring forth great spiritual fruit!

To begin with, the setting of this parable is worth taking note. It is all about workers chosen to labor in a vineyard. Grapes cultivated and grown are ready to harvest, and the vineyard’s owner is in pressing need of laborers to reap the bounty from the vines. Understanding the Biblical and Jewish usage of a vineyard is thus significant for us to appreciate all that the parable conveys. While vineyards are mentioned in scattered references in the Hebrew Scriptures, of particular importance is the context of the vineyard in the book of Isaiah. In chapters 1, 3, and 5, the prophet prominently features a vineyard in his prophecies and directly links it to the Hebrew people and nation. The vineyard produces abundant fruit that needs reaping so others may benefit from its goodness. Yeshua uses this concept to form the basis for the parable. This is all about laboring for what belongs to the Holy One. As a people, Israel has a purpose in this world – to bear and to bring forth great spiritual fruit!

This idea of connecting the vineyard to the Hebrew people is also strongly maintained in extra-biblical Jewish writings, such as the Mishnah, Ketuvot 4:6; the Talmud Bavli, tractates Berakhot 63b, Bava Batra 131b, and Yevamot 42b; and also in the Aramaic Targum to Ecclesiastes 2:4. In each of these passages, the term for “vineyard” KEREM, is used and distinctly signifies not only the Jewish people, but more specifically the Jewish religious authorities responsible for the nation at that time. This idea about the vineyard referring to Jewish authorities is also echoed by Yeshua once again in another parable preserved in Matthew 21. This proper identification is important for the reader to recognize the spiritual application of the parable’s content. In the Aramaic text of the Peshitta, the term for “vineyard” is KARMA, being merely the cognate of the Hebrew KEREM, providing for us an uncontested link in theme.

We can now move to the insightful nuances of the parable contained in the Aramaic text of the Peshitta.

Verses 1-2 give us the setting and initial situation of the parable: the owner of the vineyard goes out at dawn to the marketplace and agrees with the day-laborers over a wage – a denarius – for them to come work for the harvest. Those laborers then begin the day’s work he has for them.

The next five verses, 3-7, detail the owner’s repeated returns to the marketplace as the day progresses to gather more laborers. Curiously, in these instances, unlike with his initial workers, he does not agree on a price with them – he rather hires them only with the standing promise that they shall be properly paid for their labor.

Verses 8-9 chronicle the payment of the laborers. The process begins with the last laborers hired receiving first the payment for their work. In this we see that even those who worked the least amount of time are given the same wage as was agreed upon by the initial workers who had been in the vineyard since dawn.

Verses 1-2 give us the setting and initial situation of the parable: the owner of the vineyard goes out at dawn to the marketplace and agrees with the day-laborers over a wage – a denarius – for them to come work for the harvest. Those laborers then begin the day’s work he has for them.

The next five verses, 3-7, detail the owner’s repeated returns to the marketplace as the day progresses to gather more laborers. Curiously, in these instances, unlike with his initial workers, he does not agree on a price with them – he rather hires them only with the standing promise that they shall be properly paid for their labor.

Verses 8-9 chronicle the payment of the laborers. The process begins with the last laborers hired receiving first the payment for their work. In this we see that even those who worked the least amount of time are given the same wage as was agreed upon by the initial workers who had been in the vineyard since dawn.

Verse 10 begins to showcase the unique richness of the parable in its Semitic wording. Those workers who had labored all day assume that, since the workers who had only labored briefly received a wage deemed worth a day’s labor, that their day-long labor would instead be much more than they had agreed upon with the vineyard’s owner. The Aramaic text of this verse has Yeshua conveying that idea in somewhat of a clever and humorous manner.

The phrase Yeshua used is SHAQLIN WASHQALAW DINAR DINAR “they should receive, and they received a denarius apiece.” The pun lay in that the word for “receive” comes from the root SHQL, which is the same letters comprising the word for the widely used Biblical-era coin known as the shekel.

The phrase Yeshua used is SHAQLIN WASHQALAW DINAR DINAR “they should receive, and they received a denarius apiece.” The pun lay in that the word for “receive” comes from the root SHQL, which is the same letters comprising the word for the widely used Biblical-era coin known as the shekel.

The term shekel was used by many peoples in the Middle East during antiquity, crossing the borders of nations and cultural and linguistic boundaries. From the birth of the Israelite nation at the foot of Sinai in Arabia to the oppression of the people under the foot of Rome during the first century, the term shekel as a form of currency was an everyday part of life for the Hebrew people. It would have been much like saying “coin,” and it being immediately known that a generic currency was just referenced. Understanding this trans-cultural usage of the term, Yeshua thus used the similar word “receive” to evoke the concept of a shekel as He spoke about the topic of payment. The ingenuity of what Yeshua did cannot be overstated. This simple detail is important for the reader to recognize, as it sets up a pun that will repeat throughout the remainder of the parable in several unique and meaningful ways.

Yeshua then uses the term DINAR. The word DINAR is of course the Aramaicized word for the Greek coin called the denarius. While it is probably impossible to arrive at an exact assessment of value, based on what is known about Biblical-era coins and the weights and values set for them, it can safely be stated that one shekel would have been about the value of two denarius coins. What should not be missed in this pun is that although the text is using the Aramaic word for “receive,” it seems like it is saying the word “shekel” twice, and then we see two clear appearances of the word for denarius. This would make it seem like those who worked all day, upon seeing the wage of a denarius for those who worked but a small fraction of that time, were themselves about to receive twice as much: DINAR DINAR “denarius, denarius,” thus they essentially were expecting a shekel! It is a clever pun on the lips of Yeshua that is unlikely to have gone unnoticed by those who originally heard this.

Moving into verse 11, the pun begun in the previous verse continues in this statement, but in a uniquely different manner: The Aramaic tells us that the laborers who had worked from dawn had “received” their one denarius, and then they murmured over the payment they now considered as unfair. This word for “received” is SH’QALAW and is a different play off the “shekel” idea they hoped to receive, for the term, if pronounced instead as SHEQAL, can alternatively be used for the idea of “take away / cutting off.” These first laborers got their “shekel” all right – their hopes had been “taken away / cut off” for a higher payment! Messiah’s word choice drives home the sense of disappoint they surely felt, even though it was unfounded in the first place.

The punning on the root of SHQL continues in verse 12. This time, it is the ungrateful laborers who try to shove their perceived injustice back in the face of the owner of the vineyard by using the term SHQL in yet another alternate definition of the word: “to bear / to carry.” Thus, they complain that it was they who DASHQALAN “who bore” the YUQREH “weight” of the day. This play further exemplifies the depth of Yeshua’s parable in the Aramaic tongue, for the term SHQL, in its root idea, simply means “weight,” and then from that root branches off into the various different usages we have seen here in the Aramaic tongue. This idea of “bear / carry” goes back to the “weight” root of the word, and that reality can be seen in the choice of YUQREH “weight” in the text of the Peshitta. The Semitic parallels would certainly have been recognized by those listening to the original parable.

This use of YUQREH in the text has a further application, as well. This is seen in that the term holds the meaning not only of “weight,” but also “price” or “cost.” Therefore, in their minds, the initial laborers felt it was they who should have “received” the “shekel” because of their “bearing” / “shekel-ing” the “price” of the day. The complexity of the repeated punning off of the Semitic root of SHQL in this parable is astounding, and appreciation of it shows us why it is so helpful to understand the words of Yeshua in their original tongue.

Verse 13 showcases the response of the vineyard owner to these ungrateful laborers, and in it Yeshua showcases His own ingenious teaching method. The unhappy laborers accused the vineyard owner in verse 12 of making the laborers who only worked for a brief period of time as “worthy” as themselves, who worked the entire day. This word for “worthy” is ASHWITH in the Aramaic, and yet can also have the meaning of “agree.” Essentially, the idea is that of equality – an agreement of worth.

The dual definition of this term is then utilized by Yeshua as a platform for the vineyard owner to address the complaints of these unhappy laborers. He speaks to the pun on their displeasure of this “worth / agreement” as well as to the repeated use of the root SHQL with the new term appearing in the text: QATZT “agreed,” which also holds the meaning of “to cut off.” Understanding this dual use of the term QATZT, we see it is an answer to the feeling they felt when the latter workers were made as “worthy” as they, when they who worked all day “received / cut off” a single denarius. The intended message is that they haggled for a price and what they settled on “cut them off” from a greater wage, so they have no right to be ungrateful for what they received. In the end, everyone got the same wage. This is a cunning reference back to the term that Yeshua used initially for “agreed” in the beginning of the parable in 20:2.

The parable ends with the words of the vineyard owner to those ungrateful laborers explaining that he has the right to give from his wealth as he so desires. Finally, in verse 16, he makes a statement that might seem rather like a departure from all the content of the parable that we have examined. He states specifically: “many are those called, and few the chosen.” Why would Yeshua choose this statement to end the parable? It seems on the surface to be somewhat out of place with the preceding content. The reason it exists is actually totally in line with what we have read – so long as we return to the Aramaic text and understand the meaning of the words Yeshua has used in the parable.

In verse 16, Yeshua used the term GAWAYA “the selected / chosen” to speak of those whom the vineyard owner personally picked in his subsequent visits to the marketplace throughout the day. This word is a widely used Aramaic term found throughout the Peshitta text. They who have been selected are markedly different than the initial laborers in that the first round engaged in a bargaining event with the owner of the vineyard and were not specifically selected by him. This can be seen if attention is paid to how the text is worded: he went out to “hire” laborers (see verse 1), but the text in the next verse then says: “Yet, he agreed…” The introduction of “yet” suggests that what happened was different than his original intent.

However, when the text speaks of the owner’s subsequent visits to the marketplace as the day progressed, there is not any mention of “agreeing” taking place between himself and the laborers. Rather, the language is repeatedly in the imperative tense in the Aramaic of the Peshitta, that is to say, a command is given to the laborers lingering in the marketplace to go to work. These ones are the truly “selected” / “chosen” ones. These are the ones who have literally been “hired” by the vineyard owner, who did not “agree” on a wage. This idea of “hiring” here in the Aramaic is the word EGAR, and yet, it has an alternative definition if pronounced as AGAR of “collect” / “gather,” showing it to essentially be a synonym for the Aramaic term GAWAYA “the selected / the collected.”

In the end, we can see that by analyzing this seemingly simple parable in the Aramaic tongue as preserved in the text of the Peshitta, it becomes something much more involved and complex. The meaning remains, but the depth of the message intended by the Messiah in its content is magnified and enriched in a way that a simple translation is unable to easily convey. Yeshua chose the words in a careful way that allowed Him to craft a clever and hard-hitting presentation of the truth of those who labor for the Kingdom of Heaven. Many will be called to the work of eternity. Fewer still will be chosen. May each of us who labor in the vineyard of the Holy One be at peace with the reward that awaits us, and work with gratefulness that we have been given a worthy purpose.

All study contents Copyright Jeremy Chance Springfield, except for graphics and images, which are Copyright their respective creators.