NITTEL NACHT

by Jeremy Chance Springfield

12/21/19

Even the most bereft of imaginations can picture it, with but a little help: a peaceful evening, quietly strolling towards midnight, held delicately in the grasp of winter’s cold hands. A darkened home hushed of words, heated by fat oak logs glowing in the stone hearth. The rich scent of baked goods hangs like pillows in the hushed air of the house. Children lay burrowed beneath too many covers, willing themselves into an uneasy sleep. A tired mother sees fitfully to the last few unfinished details beneath the fir tree in the living room, that all might be perfect for the events to occur in the early morning. Nearby, a father snores lazily in his soft chair, an empty glass of milk drooping in his hand and crumbs of devoured sugar cookies sprinkling his shirt like snowflakes. The last few fleeting hours of the 24th of December can be envisioned with not much difficulty in the minds of most people inhabiting the Western world.

It is the night celebrated as holy by many millions of people around the world. Poignantly picturesque and sublime in nostalgia, even to a multitude of secularists the time is esteemed.

Surprisingly, for many Jewish people that silent night also comes with its own unique traditions – ones that might seem rather bizarre to anyone unfamiliar with history and the lingering power of customs. Some who are of Ashkenazi descent and many Hasidic groups observe the last several hours of Christmas Eve in a manner not so nostalgic and sweet as their Christian counterparts.

While on Christmas Eve observant Christians celebrate their time variously in festive or reverent tones, for many Jews, it is a time known as Nittel Nacht, and the details surrounding it are decidedly foreign to the modern Western mind.

Surprisingly, for many Jewish people that silent night also comes with its own unique traditions – ones that might seem rather bizarre to anyone unfamiliar with history and the lingering power of customs. Some who are of Ashkenazi descent and many Hasidic groups observe the last several hours of Christmas Eve in a manner not so nostalgic and sweet as their Christian counterparts.

While on Christmas Eve observant Christians celebrate their time variously in festive or reverent tones, for many Jews, it is a time known as Nittel Nacht, and the details surrounding it are decidedly foreign to the modern Western mind.

The name Nittel Nacht is one whose meaning is debated. In the Yiddish language, NACHT is certainly “night,” but it is the term NITTEL whose precise etymology is in question. Many consider it a Yiddish form of the Latin NATALIS, that is, “Birthday,” which is used to refer to the traditional observance of the birthday of the Messiah Yeshua, held by Christians to be on the 25th of December via Roman Catholic counting method, and the 7th of January via the Eastern Orthodox reckoning. In fact, Nittel Nacht is known among those espousing a December 25th date as Nittel Hakatan “The Small Nittel,” and those espousing a January 7th date as Nittel Hagadol “The Large Nittel,” due to the minority and majority observances in their respective locales.

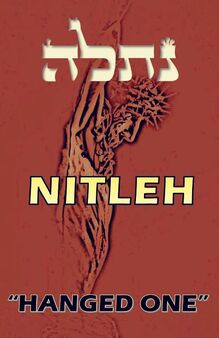

An arguably more popular explanation of the word NITTEL is it is derived instead from the Hebrew term NITLEH, meaning “Hanged One,” and is used in reference to the crucifixion of Yeshua upon the cross. The gruesome manner of Yeshua’s death was certainly seared into the minds of the Jewish people from the centuries of exposure to the Christian religion – on banner, statue, and icon, the symbol of crucifixion was inescapable. Yeshua was given that single referent to speak of the end He faced so long ago: NITLEH – the “Hanged One.” It is therefore entirely possible that NITTEL could be a reference to that Hebraic term. Otherwise, there is the potential that the term NITTEL was chosen merely due to the fact it could be viewed in such polysemous light to yield different intent depending on the context. Whatever the case may have been, the term is definitely used to reference the time known to the Gentile world as Christmas Eve.

An arguably more popular explanation of the word NITTEL is it is derived instead from the Hebrew term NITLEH, meaning “Hanged One,” and is used in reference to the crucifixion of Yeshua upon the cross. The gruesome manner of Yeshua’s death was certainly seared into the minds of the Jewish people from the centuries of exposure to the Christian religion – on banner, statue, and icon, the symbol of crucifixion was inescapable. Yeshua was given that single referent to speak of the end He faced so long ago: NITLEH – the “Hanged One.” It is therefore entirely possible that NITTEL could be a reference to that Hebraic term. Otherwise, there is the potential that the term NITTEL was chosen merely due to the fact it could be viewed in such polysemous light to yield different intent depending on the context. Whatever the case may have been, the term is definitely used to reference the time known to the Gentile world as Christmas Eve.

The traditions held by those who observe it are very different than the Western merriments occurring in the homes of their neighbors. The most recognized of these several traditions are here mentioned in order for us to understand some intriguing spiritual truths about this unique Jewish observance predicated upon a Gentile holiday.

Carolers on the 24th of December are not typically met with warm greetings at the door of a Jewish home observing Nittel Nacht. Rather, the door is shut and purposefully not opened while the clocks tick towards midnight. Inside, parents solemnly explain that in days gone by (think Medieval Era) the Jewish people of Central-Eastern European countries feared to venture out on this night due to an increase in persecution from those unfortunate ones who, having left the rousing evening services in their various churches, were prone to seize and bitterly accost any Jew found wandering about, spurred into zealous wrath by the misplaced teaching that Jewish people were responsible for the death of the Messiah and thus in need of some form of punishment in their eyes. The nostalgia of the evening so widely held by most today is lost upon many Jewish minds, filled instead with the dread of that haunting specter of religious persecution which, thankfully, has long-since ceased to be a yearly event in the modern world.

Carolers on the 24th of December are not typically met with warm greetings at the door of a Jewish home observing Nittel Nacht. Rather, the door is shut and purposefully not opened while the clocks tick towards midnight. Inside, parents solemnly explain that in days gone by (think Medieval Era) the Jewish people of Central-Eastern European countries feared to venture out on this night due to an increase in persecution from those unfortunate ones who, having left the rousing evening services in their various churches, were prone to seize and bitterly accost any Jew found wandering about, spurred into zealous wrath by the misplaced teaching that Jewish people were responsible for the death of the Messiah and thus in need of some form of punishment in their eyes. The nostalgia of the evening so widely held by most today is lost upon many Jewish minds, filled instead with the dread of that haunting specter of religious persecution which, thankfully, has long-since ceased to be a yearly event in the modern world.

Christians might be engaged on this night in family dinners and happy revelry, but for those observing Nittel Nacht, it is a toned-down experience. In place of holiday treats or festive meals is the tradition of eating bitter garlic in attempt to ward off the perceived spirits of the season. Cards, often a game forbidden or at least much maligned by religious authorities at other times of the year, are at this time, inexplicably, a game of choice. Chess also joins the game of cards as a popular past time among those who participate in the traditions. In fact, even some of the more austere rabbis in Hasidic groups have been known to pass the hours until midnight immersed in quiet chess stratagems.

Inside these shuttered houses, the inhabitants are not snuggled warm in their beds, but are encouraged to stay wide awake the whole night long, keeping also from attending to restroom needs, for tales of horror are handed down: the Christian Messiah, it is whispered, is said to return to earth on this night, going about through the streets and seeking to harm or snatch away any Jew who might be found in need of relieving himself on the toilet. Admittedly a bizarre thought, it is yet one that long instilled fear in the minds of those to whom it was taught.

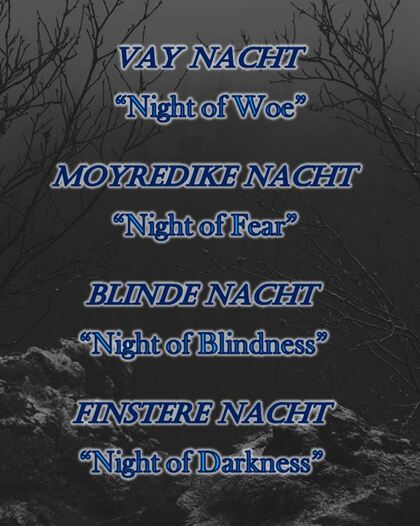

The horror of persecution once experienced by Jewish people on this night has been preserved not only in these customs, but also in the various names given to the night that express the racial memory of how terrifying it once was on this day to be Jewish in Medieval times.

The horror of persecution once experienced by Jewish people on this night has been preserved not only in these customs, but also in the various names given to the night that express the racial memory of how terrifying it once was on this day to be Jewish in Medieval times.

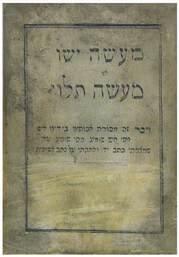

On this night of nights, while the Christian world often recounts the story of the birth of Messiah, those Jewish people who are instead celebrating Nittel Nacht might just be found reading such texts as Toledot Yeshu, or Ma’aseh Talui (also known as Asham Talui). These Medieval Jewish texts are warped and mangled accounts of the actual historical Messianic record preserved from antiquity in the Gospels, where the story faithfully held there is instead here turned on its head in an attempt to portray the Christian Messiah to be a false hope who led astray his own people.

While it may sound incredibly ironic that many Jews would even be found reading about the Messiah Yeshua on Christmas Eve, that is precisely what one of the major traditions consists of for those who observe Nittel Nacht. To be sure, the story that is read is not the same story that is contained in the legitimate Gospel accounts, but it is incredibly interesting that on the 24th of December, both Gentile and Jew alike unite in unexpected focus upon the man who has so transformed and challenged the entire world in the last two thousand years. This facet of the night is too astounding to ignore. A great spiritual truth is contained in this reality that shall be further discussed as this study develops.

While it may sound incredibly ironic that many Jews would even be found reading about the Messiah Yeshua on Christmas Eve, that is precisely what one of the major traditions consists of for those who observe Nittel Nacht. To be sure, the story that is read is not the same story that is contained in the legitimate Gospel accounts, but it is incredibly interesting that on the 24th of December, both Gentile and Jew alike unite in unexpected focus upon the man who has so transformed and challenged the entire world in the last two thousand years. This facet of the night is too astounding to ignore. A great spiritual truth is contained in this reality that shall be further discussed as this study develops.

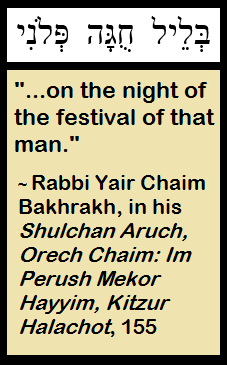

Indeed, on Nittel Nacht / Christmas Eve, not only is the reading of such scandalous texts a tradition, perhaps the most shocking of customs is the unthinkable: it is viewed on this night as vitally important to refrain from any study of the holy Torah, or even other widely recognized and precious religious texts. All positive spiritual study is foregone for the evening, practitioners intentionally engaging in what is known in Judaism as the act of Bitul Torah – the abandoning of the Torah. In fact, the Satmar Hasidim are known for referring to Nittel Nacht instead as Bitel Nacht “Night of Nullifying [Torah study].” There is even some speculation that the name NITTEL actually stems from the Yiddish term NIT “nothing,” and refers to this very practice of ceasing Torah study on Christmas Eve. The earliest reference to this is from a 17th century text by Rabbi Yair Chaim Bakhrakh, called Mekor Hayyim.

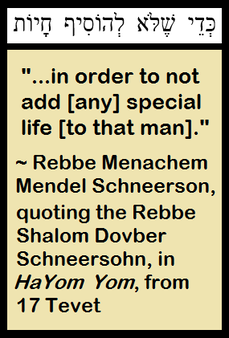

We see from this very brief mention that the purpose of not studying the Torah on Nittel Nacht has to do with PLONI – “that man,” which is a generic reference to the Messiah Yeshua.

The reason, interestingly, is decidedly spiritual, as explained by the late Rebbe Menachem Mendel Schneerson of Lubavitch, who, writing in HaYom Yom, quoted from a previous Rebbe that the purpose of abstaining from Torah study those few hours was explicitly intended to be in spiritual opposition to the Messiah Yeshua.

The reason, interestingly, is decidedly spiritual, as explained by the late Rebbe Menachem Mendel Schneerson of Lubavitch, who, writing in HaYom Yom, quoted from a previous Rebbe that the purpose of abstaining from Torah study those few hours was explicitly intended to be in spiritual opposition to the Messiah Yeshua.

Such surprising reason for the act of abandoning Torah study on this night is repeated in very similar words by Rebbe Menachem Mendel Schneerson in Siach Sarfei Kodesh, 192. Those who observe this ban do so because they believe that Yeshua the Messiah returns on that particular night, and the righteous spiritual act of studying the holy Torah would give special merit to His spirit at that time. Therefore, in order to prevent such positive spiritual merit from being given to Yeshua, the study of the Torah is instead annulled for those few hours on Nittel Nacht.

It may seem wondrous how these customs ever arose, yet with but a little investigation into the antics of some Medieval people in Central-Eastern European countries at that time of year, we will find a very ironic explanation for such odd Jewish behavior.

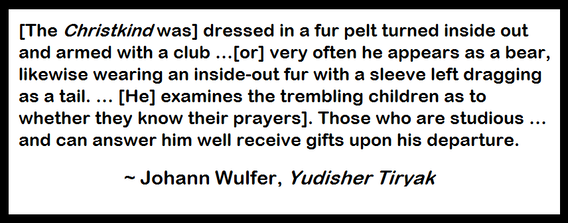

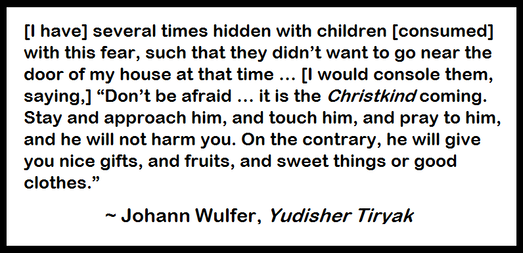

Medieval times were an era when superstition reigned widespread for many peoples in the European continent, and according to the words of Johann Wulfer, writing in Yudisher Tiryak in 1681, certain holiday customs had a greater affect upon the populace than actually intended, as originally presented in Rebecca Scharbach's excellent research in The Ghost in the Privy: On the Origins of Nittel Nacht and Modes of Cultural Exchange. In that text, he records a tradition among some people of the Eastern Orthodox persuasion to have an individual dressed up and go about the neighborhoods as the Christkind, a “unique” representation of the Christian Messiah. Unfortunately, this representation was not quite literal, but startlingly bizarre to our modern sensibilities. The following quotation from his account gives a clear example of a popular portrayal of this type.

It may seem wondrous how these customs ever arose, yet with but a little investigation into the antics of some Medieval people in Central-Eastern European countries at that time of year, we will find a very ironic explanation for such odd Jewish behavior.

Medieval times were an era when superstition reigned widespread for many peoples in the European continent, and according to the words of Johann Wulfer, writing in Yudisher Tiryak in 1681, certain holiday customs had a greater affect upon the populace than actually intended, as originally presented in Rebecca Scharbach's excellent research in The Ghost in the Privy: On the Origins of Nittel Nacht and Modes of Cultural Exchange. In that text, he records a tradition among some people of the Eastern Orthodox persuasion to have an individual dressed up and go about the neighborhoods as the Christkind, a “unique” representation of the Christian Messiah. Unfortunately, this representation was not quite literal, but startlingly bizarre to our modern sensibilities. The following quotation from his account gives a clear example of a popular portrayal of this type.

The strange choice to dress as a bear makes no real sense but was apparently a traditional garb for many. Additionally, the identity of the Christkind was not even always a man, but, as the text quoted above continues to explain, was often taken up by a maiden. Perhaps it was this tendency for a female to assume the bear identity that the Christkind was replaced in some locales with the costumed character of Frau Perchta, who is described as a woman who would go about the neighborhood and check on the children and servants, questioning them on their knowledge of prayers and their character, giving out treats to those deemed worthy, and threatening bodily injury to those who fell short. In fact, she was said to carry a blade or fork of some type and would threaten to disembowel those who were found wanting in these areas or awaiting until sleep overtook them to remove their intestines. The above text of Yudisher Tiryak mentions the account of one who spoke of the fear this strange manifestation of the Christkind would induce upon the youths in these locales.

These odd superstitious customs, while originating in certain Medieval Christian communities of Central-Eastern Europe, apparently did not remain only with the Christian community to which they were intended, but became a memory imprinted upon the Jewish people living among them, who inculcated these basic concepts in an adapted format of fear and mockery. These encounters, witnessed either first-hand or as by-standers, were seared into the collective memory of the persecuted Jewish community, and so largely became the core from which grew further unique traditions observed on Nittel Nacht. The Jewish customs of not going out on that night, of staying awake indoors, of not attending to bodily needs, and so forth, are clearly derived from some degree of encountering these unfortunate Christian outlier customs which took place on Christmas Eve.

This odd Jewish observance stemming from a Gentile holiday begs the question: Why would the Holy One allow His chosen Messiah to continue to suffer such mockery and disdain by the very people to whom He was promised? We cannot know the mind of the Most High. But we can trust that His plan is perfect. While some questions might be unanswerable, to this one an answer is thankfully evident from the pages of Scripture itself. However, to arrive at that answer, we first have to understand something more about the seriousness of the Jewish act of abandoning the study of Torah on Nittel Nacht / Christmas Eve.

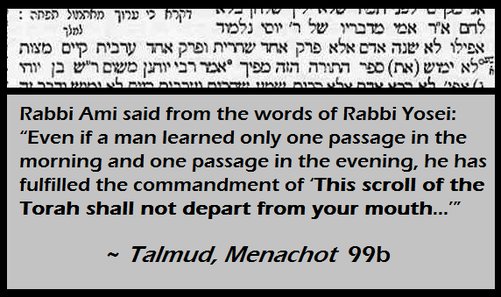

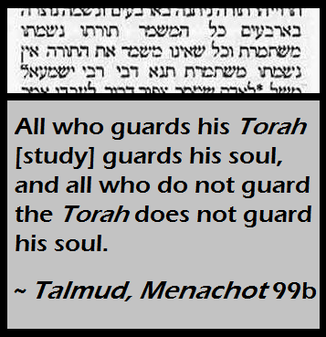

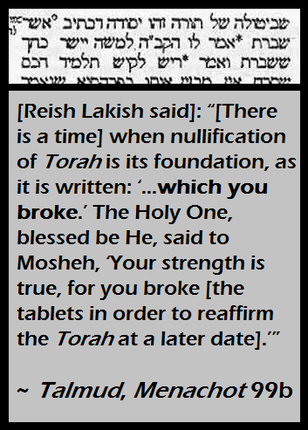

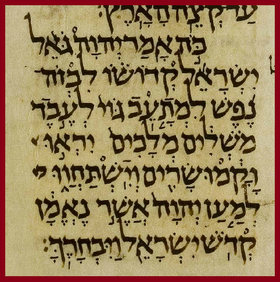

The sages of Judaism have made it clear that Torah study is a daily commandment for all to fulfill. In fact, in the Talmud, tractate Menachot 99b, we read about this very thing.

The sages of Judaism have made it clear that Torah study is a daily commandment for all to fulfill. In fact, in the Talmud, tractate Menachot 99b, we read about this very thing.

The rabbis derived through a brief quoting of Joshua 1:8 that it was incumbent to engage in some degree of Torah study at least every day. The purpose of this daily study is manifold. It is said to do a very specific thing, as explained elsewhere in the same tractate of the Talmud.

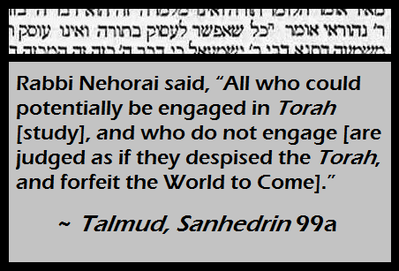

In this statement, daily study of Torah is understood to be a divine guard for the person who makes the effort to make the things of the Most High important to him. To guard it through daily study is important, for one who has the ability to do so, and intentionally refrains, reaps judgment upon themselves, a thought brought forth elsewhere in the Talmud, in tractate Sanhedrin 99a.

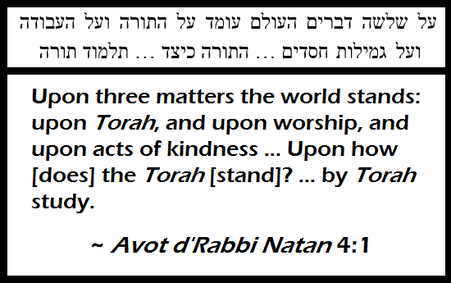

The tradition for many in Judaism to cease from Torah study on Nittel Nacht / Christmas Eve is, therefore, a truly astounding thing to consider in light of the clear and long-held Jewish understanding about the vital significance of studying Torah. To engage in Bitul Torah is viewed as incredibly dangerous in a spiritual sense. The reason for this is that the study of Torah is actually considered in Judaism as the foremost of three matters upon which the entire world subsists. This idea is recorded for us in the Avot d’Rabbi Natan 4:1, where we read the words of Simon the Just on the topic.

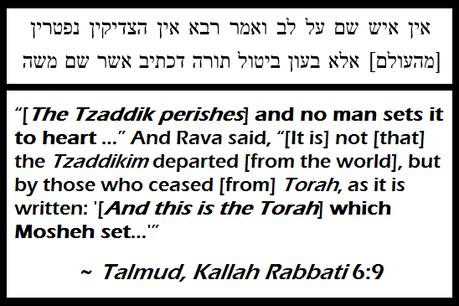

Study of the will of the Most High as revealed to the world through the text of the Torah is the first matter upon which the world stands. The neglect of this potentially endangers all of creation. And yet, that is precisely what many in Judaism do on the 24th of December. The reason, as mentioned above in the quote from the late Lubavitcher Rebbe, Menachem Mendel Schneerson, is in order that a perceived special life not be bestowed upon Yeshua on that particular night through Torah study. This seemingly odd concept is actually one derived straight from Scripture itself, as recorded in the minor Talmudic tractate of Kallah Rabbati 4:1.

This intriguing understanding of Isaiah 57:1 is based off the shared term SAM “set” linking between that passage and another one from Deuteronomy 4:44. The concept at work is that that which is “set” upon the heart is the Torah, and to disregard it by way of Bitul Torah is the reason that a Tzaddik (righteous person) is said to die. Applying this idea to Yeshua, who was understood to be a Tzaddik in 9 different passages (see: Matthew 27:19, 24; Luke 23:47; Acts 3:14, 7:52, 22:14; 1st Peter 3:18; and 1st John 2:1, 3:7), we discover a startling answer: the cessation of Torah study on Nittel Nacht / Christmas Eve by many in Judaism is done specifically to attempt to prevent any special Torah-derived life given to Yeshua, for He is understood to have been a Tzaddik even by those who are rejecting His role as the Messiah today! Hence, the idea is that if Torah study preserves the life of a Tzaddik, then Bitul Torah does the opposite – and therefore, if Yeshua is viewed as a Tzaddik, abandoning such study on Nittel Nacht is a direct attack on His unique status.

This ceasing of studying Torah on Nittel Nacht in order to prevent Yeshua from receiving any special life from the merit of such study is viewed as a dangerous but necessary act. Doing this (seemingly) to Yeshua is seen as potentially disrupting all of creation, as is understood from the unique wording of Proverbs 10:25.

This ceasing of studying Torah on Nittel Nacht in order to prevent Yeshua from receiving any special life from the merit of such study is viewed as a dangerous but necessary act. Doing this (seemingly) to Yeshua is seen as potentially disrupting all of creation, as is understood from the unique wording of Proverbs 10:25.

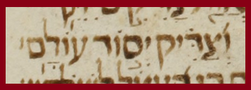

and a righteous person is the foundation of the world.

While the majority of English translations based off Christian translators yield something similar to “the righteous is (or “are”) an everlasting foundation,” the literal Hebrew actually reads VETZADDIK YESOD OLAM – “and a tzaddik is the foundation of the world.” This reading is the traditional Jewish understanding of the text. The concept is the Tzaddik supports the entire world by his special merit before the Most High. If the Tzaddik is removed, therefore, the entire world is in danger, and yet that is exactly what we see attempting to be done by Jewish people who observe Nittel Nacht – the world is put in potential danger for the purpose of showing dishonor to Yeshua as the Messiah on a night taken to be significant to many of His followers.

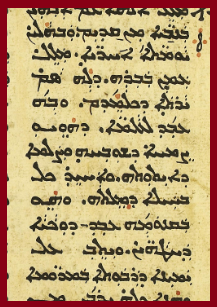

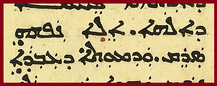

This concept of the Tzaddik being the foundation of the world is one that is supported also by various readings in the New Testament texts, as well, showing that the Jewish manner of reading the verse shared above from Proverbs is the valid interpretation. We see this concept applied to Yeshua in the texts of the New Testament, examples of which I share here as translated from the Aramaic Peshitta.

This concept of the Tzaddik being the foundation of the world is one that is supported also by various readings in the New Testament texts, as well, showing that the Jewish manner of reading the verse shared above from Proverbs is the valid interpretation. We see this concept applied to Yeshua in the texts of the New Testament, examples of which I share here as translated from the Aramaic Peshitta.

HEBREWS 1:2-3

2 and in these latter days [the Deity] spoke with us by His son, of whom He placed the heir of every thing, and in whom He made the worlds,

3 who is the illumination of His glory, and the figure of His essence, and holds all in the power of His Word. And he, in his own substance, made the cleansing of our sins, and was seated on the right of the Greatness on high.

Thus we see the idea of the Tzaddik supporting the world clearly emphasized in the minds of first-century Jews writing to display the central importance of Yeshua in that role. Proverbs 10:25 is rightly understood as the Tzaddik being the foundation for the world.

To perform Bitul Torah on Nittel Nacht, therefore, is thus to reject the Tzaddik who is viewed as upholding the world – a dangerous deed, but in the eyes of many Jewish individuals who refrain from Torah study on that night, it is necessary. However, one must surely ask: If Torah is abandoned on that silent night – if no Tzaddik is given special life by the merit of studying the Word, then how does the world persist? Why would the Holy One allow such a horrible thing to take place to the Chosen One? Why allow such mockery and contempt to be intentionally directed to the Messiah?

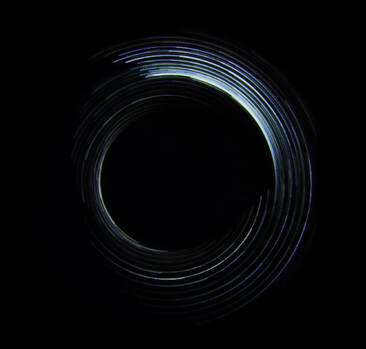

The answer is that the world has a second manner of support and understanding that particular manner properly displays the prophetic reason why Messiah is ridiculed and mocked in such a way. This other manner of being upheld is not so readily perceived, and yet, is distinctly conveyed in the Word. Turn now to the ancient words found in the book of Job 26:7 and let us see the surprising truth.

To perform Bitul Torah on Nittel Nacht, therefore, is thus to reject the Tzaddik who is viewed as upholding the world – a dangerous deed, but in the eyes of many Jewish individuals who refrain from Torah study on that night, it is necessary. However, one must surely ask: If Torah is abandoned on that silent night – if no Tzaddik is given special life by the merit of studying the Word, then how does the world persist? Why would the Holy One allow such a horrible thing to take place to the Chosen One? Why allow such mockery and contempt to be intentionally directed to the Messiah?

The answer is that the world has a second manner of support and understanding that particular manner properly displays the prophetic reason why Messiah is ridiculed and mocked in such a way. This other manner of being upheld is not so readily perceived, and yet, is distinctly conveyed in the Word. Turn now to the ancient words found in the book of Job 26:7 and let us see the surprising truth.

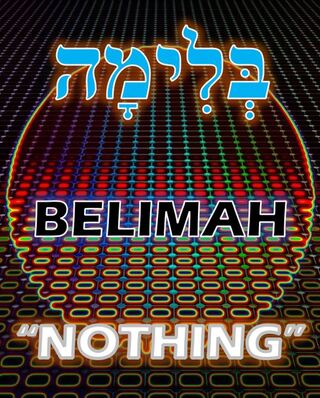

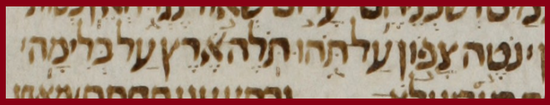

He stretches the north upon emptiness; He hangs the earth upon nothing.

The Tzaddik in his merit is the foundation upon which the earth sits, but the second support for the earth is the most unexpected statement: it is suspended on nothing! The term in the Hebrew text that I have here translated as “nothing” is BELIMAH, and is a compound word in the language, to be read as BELI-MAH – literally, “what is nothing.” The term is somewhat rich in meaning and worthy of discussing in those facets, but before that is addressed, let us first look at the term’s central concept of “nothing” and see how it relates to the above topic.

The idea of the world being upheld by BELIMAH “nothing” points us also to Yeshua in an unexpected way. He let go of all that He had – ego, stature, the value of His own spiritual merit, and became as nothing to fulfill the redemptive plan of the Most High. We see this reality expressed in Philippians 2:7.

but instead, his soul was emptied, and the image of a servant he took...

In order for Yeshua to perform the prophetic role assigned to Him – of the utterly rejected Messiah – His complete rejection had to be undertaken to the point of becoming emptied and nothing in the view of His own people. This is the position He holds in the eyes of many Jewish people who deny His status as the Messiah, while unknowingly proving Him to be the one prophesied to come. In this perspective Yeshua becomes the second support for the world. Stripped of the merit of a Tzaddik by the Bitul Torah act of many Jews on Nittel Nacht, Yeshua instead supports the world by way of the truth uttered for us in Job 26:7. The world is thus safeguarded from any danger of being overturned due to the selfless role of Yeshua as the appointed nothing that upholds the world.

The second alternate possible meaning of BELIMAH could stem from the idea of “what has failed.” In this sense, Yeshua also can be seen as fulfilling a prophetic role in such manner. Isaiah 49:7 preserves this thought about the Messiah.

The second alternate possible meaning of BELIMAH could stem from the idea of “what has failed.” In this sense, Yeshua also can be seen as fulfilling a prophetic role in such manner. Isaiah 49:7 preserves this thought about the Messiah.

To the despised of man, to the loathed one of the nation, to the servant of rulers…

Who else would fit this description? There is but one man who has been held in such contempt for two millennia by the nation of Israel, and we all know who that is. Yeshua, the Messiah rejected by the people, but chosen by the Holy One for that scandalous calling, is the only one who can be rightly identified as the intent of that prophecy. Not often is this prophetic detail mentioned when one reads about the qualities of the Messiah, and yet, it is a very real facet of His character. He must be despised and loathed by the people.

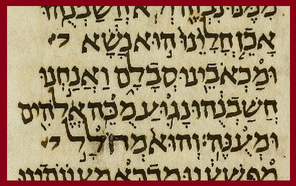

The third alternate possible meaning of BELIMAH could stem from the idea of “what is afflicted.” In this aspect, Yeshua also shows Himself as rightly fulfilling the concept. The famous passage of Isaiah 53:3 succinctly shows this truth.

The third alternate possible meaning of BELIMAH could stem from the idea of “what is afflicted.” In this aspect, Yeshua also shows Himself as rightly fulfilling the concept. The famous passage of Isaiah 53:3 succinctly shows this truth.

Indeed, he has borne our sickness and carried our pains, and we reckoned him stricken, beaten of Elohim, and afflicted.

Yeshua was afflicted physically and spiritually. He bore the weight of the cross, the beatings of man, the crucifixion nails, and even more so, the judgment of our sin in order to rectify all iniquity. He was broken physically and spiritually in order to touch every realm affected by the sin of mankind. He alone has fulfilled the role of the Servant in this most literal sense.

In these things we see Him not as the Tzaddik, but as the nothing, as the failure, as the afflicted one – all prophetic roles that go back to the unseen support for the world in answer to the spiritual danger of Bitul Torah – abandoning the Torah.

In these things we see Him not as the Tzaddik, but as the nothing, as the failure, as the afflicted one – all prophetic roles that go back to the unseen support for the world in answer to the spiritual danger of Bitul Torah – abandoning the Torah.

It is in this most unbelievable of acts that the Jewish people have engaged in on Nittel Nacht that we see the truest role of Yeshua in the most unlikely of prophetic facets. He must be the answer to the sin of nullification of the Torah. And so, we see even in the most extreme situation, the Tzaddik upholds the world in merit unparalleled. Furthermore, we see the choice to cease the Torah by the Jewish people is prophetically significant and allows us to appreciate the depth of the nature of the Messiah in His saving role for mankind. Returning to the words of the Talmud, again to tractate Menachot 99b, we read of this concept being proposed even so long ago.

Nullifying the Torah can be its very foundation at times: what seems to be the worst idea, the most dire of decisions, can turn out to be the only path forward for His people. On Nittel Nacht, many Jewish people turn away from Torah, unknowingly bringing the role of Messiah to His most astonishing completion - a Tzaddik brought to nothing so that, as the nothing, He is able to uphold the world in a manner that is the most unexpected, but is also prophetically necessary.

Sometimes, it is only in the worst of situations that we are able to see the hope of redemption. There is always the presence of the plan of restoration even when we feel things are most estranged from His desire for the world. Even on the darkest night of the year, where Jews and Gentiles are largely united in mind - even though from polarized religious perspectives - the Holy One has provided a light to let us see the redemption that awaits, when Jew and Gentile alike will sit in harmony and worship the Most High as one people. On Nittel Nacht and Christmas Eve, a powerful spiritual truth upholds the world by the abounding mercies of the Most High, and is a comfort for all who desire to see the Kingdom come upon this earth.

Sometimes, it is only in the worst of situations that we are able to see the hope of redemption. There is always the presence of the plan of restoration even when we feel things are most estranged from His desire for the world. Even on the darkest night of the year, where Jews and Gentiles are largely united in mind - even though from polarized religious perspectives - the Holy One has provided a light to let us see the redemption that awaits, when Jew and Gentile alike will sit in harmony and worship the Most High as one people. On Nittel Nacht and Christmas Eve, a powerful spiritual truth upholds the world by the abounding mercies of the Most High, and is a comfort for all who desire to see the Kingdom come upon this earth.

All study contents Copyright Jeremy Chance Springfield, except for graphics and images, which are Copyright their respective creators.