FOOL ME ONCE

by Jeremy Chance Springfield

4/2/17

The Biblical text is a clear light into the darkness of this world, but one area that still seems to cast shadows in the halls of the erudite is that of New Testament language primacy. A debate exists among scholarly circles concerning the original language and text used for the New Testament writings. The traditional consensus is Greek was the language used, and the preponderance of manuscript evidence has caused the majority of scholastic discussion to support that particular perception. Two other languages have also been proposed to have been the original ones used by the Messiah and His early followers – Hebrew and Aramaic, and texts utilizing those languages have also been presented in the debate. All manner of reasons exist in the three camps as to why their assertion is to be preferred, but as a translator of His Word, I will share a fact that should help clear away emotionally-based and untenable reasons, and zero in on what matters in the discussion: textual details preserved in the manuscripts themselves should be what ultimately drives all opinion when it comes to language primacy of the New Testament.

To those outside the scholarly circles of debate, the question may resound in their ears: of what importance is it to know in which language the original texts were penned? How does knowing for sure really help? What does it matter so long as the message of redemption provided by the Messiah is conveyed accurately? Isn’t debate about it a waste of time?

It should yet be made clear that while it may not be a pressing topic for the Body at large, illuminating which language was originally used to record the chronicles of the Messiah and His students is more significant than one might initially imagine. For instance, if there is error concerning the language touted as legitimate, then the consequences of such an error will inevitably surface, and the result will irrevocably be the potential damaging of the true faith.

The goal of this study is to share just one instance from the New Testament that displays why the discussion on language primacy of the Messianic texts is at the vital core of our faith, albeit not something that is widely understood or considered. I have chosen just two brief passages out of all of the New Testament texts to highlight the importance of being able to discern which language was originally used by our Messiah and those responsible for writing down His words. The weight of the matter is greater than typically assumed, as the consequences can potentially have devastating results on the integrity of His Word.

To those outside the scholarly circles of debate, the question may resound in their ears: of what importance is it to know in which language the original texts were penned? How does knowing for sure really help? What does it matter so long as the message of redemption provided by the Messiah is conveyed accurately? Isn’t debate about it a waste of time?

It should yet be made clear that while it may not be a pressing topic for the Body at large, illuminating which language was originally used to record the chronicles of the Messiah and His students is more significant than one might initially imagine. For instance, if there is error concerning the language touted as legitimate, then the consequences of such an error will inevitably surface, and the result will irrevocably be the potential damaging of the true faith.

The goal of this study is to share just one instance from the New Testament that displays why the discussion on language primacy of the Messianic texts is at the vital core of our faith, albeit not something that is widely understood or considered. I have chosen just two brief passages out of all of the New Testament texts to highlight the importance of being able to discern which language was originally used by our Messiah and those responsible for writing down His words. The weight of the matter is greater than typically assumed, as the consequences can potentially have devastating results on the integrity of His Word.

When it comes to those asserting the Greek language as the original, there are essentially five different text types of New Testament manuscripts that must be considered in the discussion:

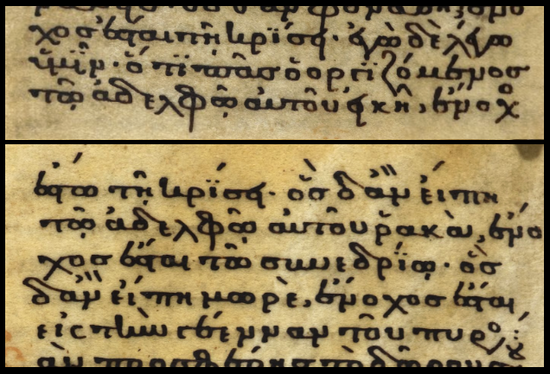

There are differences in each of these manuscript types, and scholarly work is devoted to identifying and classifying each manuscript and fragment of the Greek into its proper designation. For the purposes of this study, however, the New Testament passages that will be considered are on the minority side of things in that there exist no known variant readings of these passages. In other words, all of the manuscripts are in agreement and read the same for the Greek passages that will be discussed in this study. The text-type used in the images that will be provided here is a Byzantine type written by the scribe Gerasimos in the 13th century.

When it comes to asserting the Hebrew language as the original of the New Testament, there are a few manuscripts that are typically brought forth for consideration. Incidentally, all are Hebrew versions that were originally used by the Medieval Jewish community in their debates and polemics against Catholicism. All are also versions of the book of Matthew. Those Hebrew manuscripts are found in Shem Tov ben Isaac ben Shaprut’s Eben Bohan, and Bishop Jean du Tillet’s text of Matthew. Sebastian Münster obtained a Hebrew text of Matthew also from a Jewish community, but unfortunately, did not preserve the text as he originally found it, but instead proceeded to excise the Hebrew text from its embedded place in the polemical writing in which it was written, correcting what he felt were “errors” along the way. For that reason, his text is ultimately rather unsuitable for use as a trustworthy account in Hebrew, but it is worth considering here. A few other Hebrew Matthews, such as Rabbi Rahabi Ezekiel’s text from 1750, and Elias Soloveichik’s text from 1869, are of undebatable recent origin, so do not factor into the study immediately at hand. For our purposes here, the Shem Tov, Du Tillet, and Münster Matthews will be consulted, as there is a movement behind both among those advocating a Hebrew text original.

Regarding those proposing the Aramaic language as the original used for the New Testament, there are a few manuscripts to be discussed. The most widely used by the Body is known as the Peshitta, of which an Eastern and Western text version exist. The Western version is a revised form of the older Eastern text, and is rightly referred to in discussions as the Peshitto as opposed to the Peshitta, so the Eastern Peshitta is the preferred text of antiquity in that regard. There exist also two different texts known as the Curetonian and the Siniatic Palimpsest in Aramaic. Both consist of most of the four Gospels, and yet are manifestly bad translations of a Greek manuscript. Indeed, the Gospel text of the Sinaitic Palimpsest was eventually scraped off and replaced with the account of the lives of female martyrs of the faith – a detail displaying how little it was regarded among the believers who originally possessed it. For our purposes here, only the Eastern Peshitta text will be utilized as a reliable text from antiquity.

Therefore, to reiterate, we will be looking at the readings of two passages out of Matthew from the following texts from different languages:

A Greek Byzantine text type

Shem Tov Hebrew Matthew

Du Tillet Matthew

Münster Matthew

Aramaic Peshitta

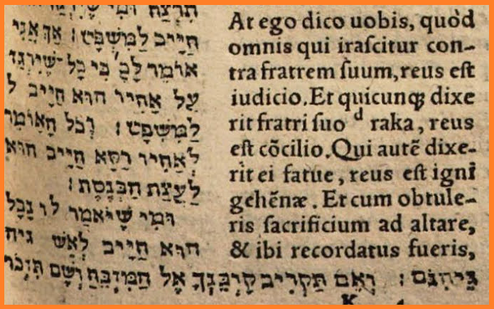

The focus of the study is on a detail from a single statement made by Messiah in the book of Matthew 5:22. It reads in the Greek as such:

“But I say to you, that everyone that is angry with his brother without a purpose shall be liable of the judgment. And whoever says to his brother, ‘contemptible one,’ shall be liable to the council. But whoever says, ‘you fool,’ shall be liable to fire of Gehenna.”

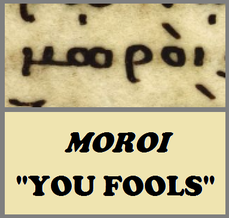

The statement He makes is straightforward. There is a line that should not be crossed. Anger is one thing, and insult is another. But giving final judgment on a person is beyond us. The word used in the Greek is MORE’, which comes from the idea of a foolish or useless person or thing. Incidentally, it just happens to be the root word from whence the English gets its term of MORON! This shows us how careful we need to be in our words when pronouncing judgment against the actions of another. Everyone has some degree of worth and insight to offer, so to render a verdict of condemnation upon another’s value is an act we are not to perform.

This statement of the Messiah is a salient one for us all to consider: there is a point in our anger where we can surpass the boundaries of personal indignation and move into the arena of our own prosecution. It is all too easy to go from the offended to the offender. In attempting to condemn another, we become the condemned by our own words. No man is exempt. The danger of punishment – the fires of Gehenna – is extended to all.

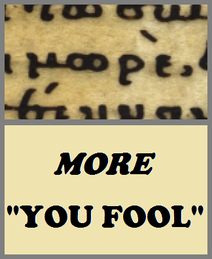

Knowing this makes the second passage we will consider in this study all the more significant. This passage comes from a lengthy speech made by Yeshua to the scribes and Pharisees that is recorded for us in the book of Matthew chapter 23. In 23:17 and 19, Messiah is recorded as saying this from the Greek text:

Knowing this makes the second passage we will consider in this study all the more significant. This passage comes from a lengthy speech made by Yeshua to the scribes and Pharisees that is recorded for us in the book of Matthew chapter 23. In 23:17 and 19, Messiah is recorded as saying this from the Greek text:

“Fools and blind ones! For what is greater: the gold or the Temple that sets apart the gold?”

~ 23:17

“Fools and blind ones! For what is greater: the gift or the altar that sets apart the gift?”

~ 23:19

In case you cannot read the Greek yet, the term which is rendered as “fools” in the two verses from Matthew 23 is the exact same term which the Messiah said the use of earns us the fires of Gehenna in Matthew 5:22! Can you see the immediate and scandalous problem that exists in the Greek text of the New Testament in these passages? Messiah said in 5:22 that calling someone by that term makes one guilty of eternal spiritual judgment, and then proceeds to call the scribes and Pharisees by that exact title! Put simply, the Greek text makes Messiah guilty of eternal punishment by the words it would have us to believe were spoken by His own mouth!

This example displays precisely why it is important to know which language text to use as a reliable source for information when reading the New Testament Scriptures. The detail shared here shows us that those proclaiming a Greek primacy of language for the New Testament texts are promoting a version that has Messiah making Himself guilty of the fires of Gehenna by His own words. Such a detail as this should cause all who otherwise would promote the Greek to pause and seriously opt to reconsider their position. The Greek texts in this instance possess no known variant readings, and so they all have Messiah uttering His own condemnation. There is no extant manuscript of the language one could point to that would resolve the problem found in the Greek. If we are being fair, we must concede that the Greek must be left behind and a resolution sought in the texts of another language.

Moving to the Hebrew versions of Matthew, we turn first to the witness of Shem Tov’s text of the Gospel. The Shem Tov Matthew is probably the most popular Hebrew New Testament text from antiquity that is in current use, so the reading from it will be telling for us all. Matthew 5:22 in his copies reads as follows:

Moving to the Hebrew versions of Matthew, we turn first to the witness of Shem Tov’s text of the Gospel. The Shem Tov Matthew is probably the most popular Hebrew New Testament text from antiquity that is in current use, so the reading from it will be telling for us all. Matthew 5:22 in his copies reads as follows:

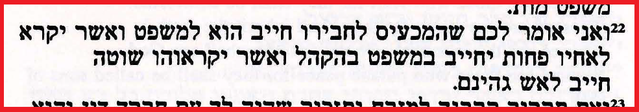

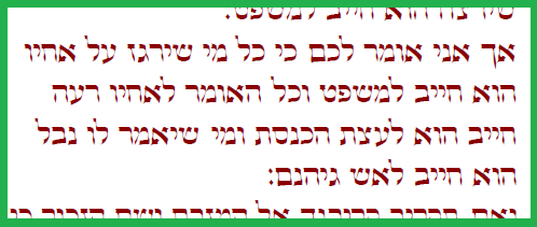

“And I say to you, ‘He who is angering to his companion is liable to judgment, and he who calls his brother “inferior” is liable to judgment with the congregation, and he who calls him “insane one” is liable to the fire of Gehinnom.’”

The Hebrew term of interest to us in this passage from the Shem Tov text is the term behind the phrase “insane one” – SHOTEH. This term is quite revealing. The word SHOTEH is not a Biblical Hebrew word. Neither does it find usage in any record of first century Hebrew terms. Rather, it comes to us preserved in Rabbinic literature from centuries later. The use of this Rabbinic term here in the Hebrew of Shem Tov’s Matthew is thus an anachronism that effectively eliminates the manuscript as being of any weight in determining which language the New Testament was originally written in. In fact, the word behind “inferior” in the same verse is also a Rabbinic Hebrew term – PAKHUTH. There are actually over one-hundred and thirty (130) other examples of Rabbinic terminology appearing in the Hebrew of the Shem Tov, which shows that it either began with such terms in its content during the Rabbinic era, or else it underwent significant revision in that era, to the degree that the original wording cannot now be uncovered.

There are those who acknowledge that the Shem Tov Matthew text has undergone rabbinic recension – possibly by Shem Tov himself. In that regard, perhaps going ahead and looking at the reading of Matthew 23:17 would be worth it. When this is done, unfortunately, it doesn’t help the matter.

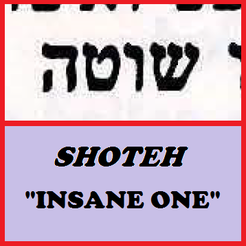

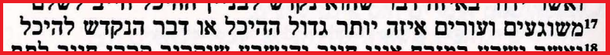

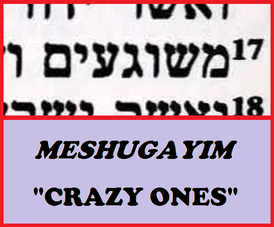

“Crazy ones and blind ones! Which is surpassingly greater: the Temple, or the thing that is set apart to the Temple?”

The Hebrew text uses a different term than SHOTEH that is found in Matthew 5:22. How does it fare? The term used here in Matthew 23:17 is the word MESHUGAYIM, meaning “crazy ones.” While it avoids the stigma of being the same Rabbinic term as previously used by Messiah, it is one that is categorically unable to have been uttered by Messiah, for MESHUGAYIM does not stem from Biblical Hebrew, and neither does it even come from Rabbinic Hebrew, but rather, it finds usage first in Yiddish – a German-Hebrew hybrid language first attested to in the ninth century CE. What this means is that not only does the text of Shem Tov’s Matthew exhibit Rabbinic Hebrew anachronistic language as if Messiah had used such terms, but also preserves Yiddish as being spoken by the tongue of the Messiah – an entirely ludicrous thought to entertain. Thankfully, at least the phrase is entirely absent from the Hebrew of Matthew 23:19, so that no further damage is done to the integrity of the Shem Tov text. Enough contamination has been exhibited in the Shem Tov Matthew, however, to show us that it is entirely unreliable in this example as to proving antiquity. If anything, it has done the opposite, proving only that it has been, at the least, altered without notation as recent as the 9th century CE.

Moving now to the Hebrew of the Du Tillet text of Matthew, we find this reading in 5:22.

“Yet, I say to you, that any who is troubling concerning his brother, he is liable to judgment; and all that say to his brother ‘evil one,’ is liable to the council of the assembly; and he who shall say to him: ‘fool,’ he is liable to the fire of Gehinnom.”

The Hebrew text here is just as revealing as the Hebrew of the Shem Tov. The word for "fool" here is the term NABAL, and is actually a Biblical term, so in itself there is no problem with its presence. However, the text contains a clear Rabbinic term that is not found in Biblical-era Hebrew. The term of importance is actually the word behind the term for “assembly” – KNESSET. There is no possibility that such a term would have been found in the mouth of the Messiah in first century Israel. This term shows yet another anachronism in the extant Hebrew Matthew texts. The presence of these anachronistic terms again eliminates the Hebrew texts as viable witnesses of antiquity, so that there is no need to examine the reading of Du Tillet's text of Matthew 23:17 or 19. No further investigation of this manuscript merits our time in this matter.

Moving on to the Hebrew text of Münster's Matthew, we read in 5:22 the following:

"But I say to you that any who is troubling concerning his brother, he is liable to judgment; and all that say to his brother, 'contemptible one,' he is liable to the council of the assembly; and he who shall say to him: 'fool,' he is liable to the fire of Gehinnom."

In this text, which is very similar to the reading from the Du Tillet Matthew (the Hebrew word for "fool" is again NABAL), we again see the anachronistic language being a problem for the veracity of an ancient and original claim regarding the Hebrew. The use of the Rabbinic term HAKNESSET here mirrors that of the Du Tillet reading, but there is also the appearance of a secondary term of consequence: the word for "liable" is the Rabbinic term KHAYAV, which has no use as such in Biblical-era Hebrew. In fact, although I bring it out here to the reader as an example only in Münster's Matthew text, it is also used in both the Shem Tov and the Du Tillet manuscripts in 5:22 - a fact the reader can return above and see plainly in the Hebrew that is included - which thus aligns all three texts with the exact same Rabbinic anachronisms. The presence of these anachronistic terms greatly damages any logical attempt to view them as valid expressions of a first-century Matthew text. For this reason, as is the case with the Du Tillet, there is really no purpose in even bringing up the reading of Matthew 23:17 or 19 from this manuscript, as the clearly unviable nature of the textual landscape has been sufficiently displayed.

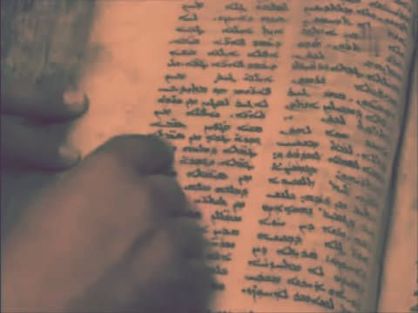

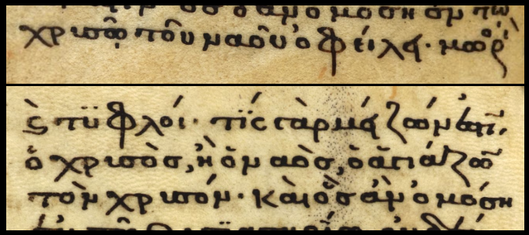

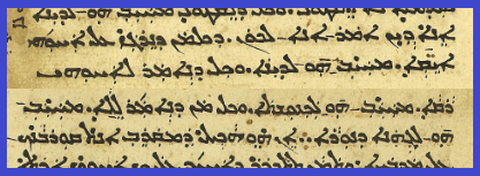

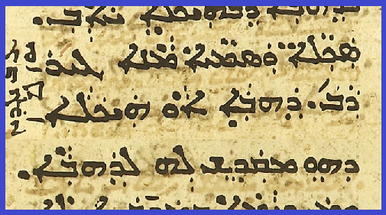

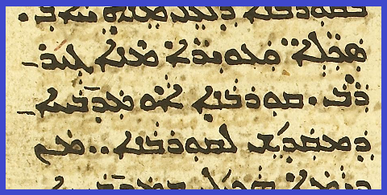

This brings us finally to the Aramaic of the Eastern Peshitta texts. The Greek proved to show Messiah as self-condemned to the fires of Gehenna – a heretical idea in the extreme. The Hebrew texts show Messiah as speaking terms from a Hebrew not yet in use, as well as a language almost a thousand years removed from His own. It falls to the Aramaic to provide an answer the other Biblical-era languages have failed so far to present. Matthew 5:22, in the Aramaic of the Peshitta, reads as thus:

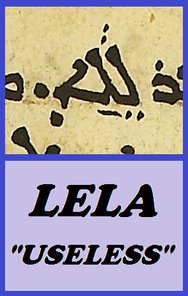

“But I, I say to you that any who shall be baselessly angry concerning his brother is liable to judgment, and any who shall say to his brother, “contemptible one,” is liable to the assembly, and all who shall say, “useless one,” he is liable to the fire of Gehenna.”

The word that the Messiah uses in this instance is LELA. It literally means “useless,” or “for naught.” It would be as severe an assessment as one could give in the Aramaic tongue. Interestingly, it is only ever used in the entire Aramaic New Testament text in this one place.

That detail prefaces the examination of the Aramaic of Matthew 23:17 and 19. The text reads as such:

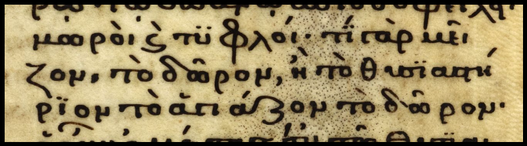

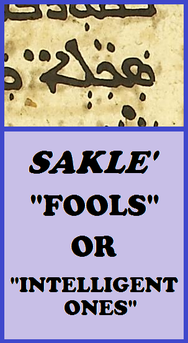

“Fools and blind ones, for what is greater, the gold or the Temple that sets apart the gold?” ~ 23:17

“Fools and blind ones, for what is greater, the offering, or the altar that sets apart the offering?” ~ 23:19

Both verses use an Aramaic term – SAKLE’, meaning “fools / stupid.” This is an interesting choice by the Messiah because of the nature of the term. Depending on the pronunciation and inflection of the term in the text, it can either be taken to mean “foolish” as in this instance, or else it can be taken as “intelligent.” Thus, the use of it here by the Messiah is a cutting single-term commentary on the rest of what He is saying to them: they are and appear intelligent about the Torah and its application in some respects, as evidenced by their careful and clinical dissection of how it can be utilized, but in certain respects, their utilization of it for selfish reasons has led to them exhibiting folly.

The text is free from the error of the Greek that makes Messiah guilty of the fires of Gehenna. It is also free from any Rabbinic Hebrew terminology. Instead, it exhibits known Aramaic terminology used at that time, and does not have Yeshua condemn Himself by calling someone in His anger by a term that He said to never use. The Peshitta text alone out of all the thousands of Greek readings and the several Hebrew Matthews can be looked at with confidence that what is being read is free from errata and anachronisms, effortlessly displaying the marks of originality as a reliable New Testament text from antiquity.

It is the Aramaic only that preserves a text free of such glaring problems. The Greek, for all the good it has done, cannot rightly be said to be the inspired, preserved spiritual text of the New Testament. The Hebrew, for all the good it would do to have a verified text in the same language as the rest of the Scriptures that proceed it, cannot rightly be said to be inspired, as the plethora of anachronistic language embedded within it makes it impossible to know if it has undergone recension or if it has always possessed those terms arising from Medieval-era texts.

This study has endeavored to show the importance of looking at the language debate surrounding the New Testament, and seeking to show how simply it can be resolved if arguments are drawn straight from the texts available to us today. The Greek and Hebrew manuscripts serve us well in our studies, but when reliability is sought after, the witness of the Aramaic stands head and shoulders above the rest. The debate can certainly continue, but the reality of the textual nature is clear for those who are willing to take the evidence at face value and admit what truths are sustained in the texts for all to see. The Aramaic of the Peshitta preserves the integrity of the message without Messianic self-indictments or anachronistic rabbinisms muddying the waters of the Word. The textual witness of the Peshitta allows the student of the New Testament to be applied completely to the integrity of its contents of hope that shine brilliantly into a dark world.

It is the Aramaic only that preserves a text free of such glaring problems. The Greek, for all the good it has done, cannot rightly be said to be the inspired, preserved spiritual text of the New Testament. The Hebrew, for all the good it would do to have a verified text in the same language as the rest of the Scriptures that proceed it, cannot rightly be said to be inspired, as the plethora of anachronistic language embedded within it makes it impossible to know if it has undergone recension or if it has always possessed those terms arising from Medieval-era texts.

This study has endeavored to show the importance of looking at the language debate surrounding the New Testament, and seeking to show how simply it can be resolved if arguments are drawn straight from the texts available to us today. The Greek and Hebrew manuscripts serve us well in our studies, but when reliability is sought after, the witness of the Aramaic stands head and shoulders above the rest. The debate can certainly continue, but the reality of the textual nature is clear for those who are willing to take the evidence at face value and admit what truths are sustained in the texts for all to see. The Aramaic of the Peshitta preserves the integrity of the message without Messianic self-indictments or anachronistic rabbinisms muddying the waters of the Word. The textual witness of the Peshitta allows the student of the New Testament to be applied completely to the integrity of its contents of hope that shine brilliantly into a dark world.

All study contents Copyright Jeremy Chance Springfield, except for graphics and images, which are Copyright their respective creators.