FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS

You know how this works. Questions and answers added as necessary.

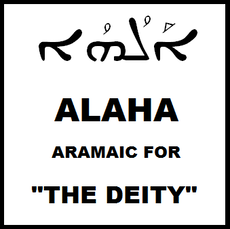

QUESTION: Why do you use the term ALAHA for “Deity” in some of your studies? Does that term have anything to do with the Muslim idol ALLAH?

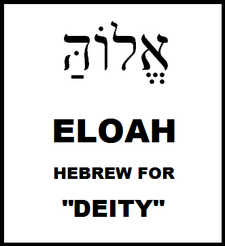

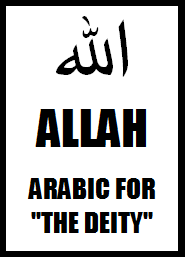

ANSWER: The title ALAHA is the Aramaic term for “Deity” used from ancient times by Aramaic-speaking peoples, both Jews and Messianic believers. It has nothing inherently in common in regards to character or personality with the Arabic idol worshipped in Islam known as ALLAH. Hebrew and Aramaic are languages of great similarity. The two languages actually share many vocabulary words (known as a “cognate” word).

The words may appear slightly different in pronunciation due to the nuances of both languages, but cognate words are essentially identical in meaning and pronunciation. In the case of the Aramaic term ALAHA, it is a title that literally means “The Deity.” Its Hebrew cognate is HA’ELOAH, which literally means “The Deity.”

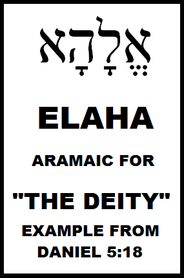

The Aramaic ALAHA is seen even in the Aramaic portions of the Hebrew Scriptures in a slightly different pronunciation, just as in Daniel 5:18, where the Creator is addressed by the prophet with the title ELAHA – the Aramaic form of that day for “the Deity.” Over time, as happens to any living language, subtle changes in pronunciation occur, and by the time of Messiah in the first century in Israel, it was common to hear the Creator being referred to as ALAHA, which had morphed in pronunciation slightly from ELAHA.

When it comes to having any relation to the Arabic ALLAH, the issue is very likely that the Arabs adopted the popular Aramaic title in that part of the world as the “name” of their particular idol – ALLAH. While most Islamic proponents will promote the idea that ALLAH comes from the Arabic phrase AL-ILAAH, meaning “the Deity,” in actuality, it almost certainly arose from the Aramaic title of ALAHA. A key point in favor of this is that the portion of –il (-IL) is specifically the Arabic root for “deity,” and it would be almost unbelievable that the root for “deity” would be what disappeared due to pronunciation by the people, leaving them to essentially not be saying the word “deity” at all when pronouncing the term of ALLAH. Such a scenario is incredibly unlikely. It would make much more sense to point to it as a loan-word / pronunciation from the dominating Aramaic term of ALAHA. This can be further pointed to by the fact that the Arabic ALLAH contains a vowel-sound not native to the Arabic language. The “ah” at the end of ALLAH is correctly pronounced as the vowels are in “caught / sought, etc.” However, such a vowel sound is not native to Arabic, but it is definitely found in Aramaic, and Aramaic was considered the lingua franca (common language) of the Middle East for over a thousand years. During the rise of Islam, Aramaic was still the dominant language of the land. It was with the spread of Islamic influence that the dominance of Aramaic began to wane, and Arabic took its place. Thus, while the Arabic pronunciation of ALLAH can be very likely traced back to the Aramaic term ALAHA, it is there that any similarity ends. The term has been found to have been in use by Arabic-speaking believers in Messiah predating the rise of the Islamic religion, and thus proves that it was a valid referent to the true Creator by His people as influenced by the dominant Aramaic tongue, before being adopted by the idolatrous cult of Islam. There is certainly no identification of ALAHA / Deity of the Hebrew and Christian Scriptures with the idol worshipped so earnestly yet so unfortunately by those currently in the Islamic faith. Therefore, let the reader wondering put aside all doubts – in no way do I call upon or elevate the Islamic idol of ALLAH by using the more ancient and fitting Aramaic term of ALAHA for “Deity.”

QUESTION: When you quote Bible verses containing names of people and places, they look much different than those names in modern English versions. Why do you do this?

ANSWER: The English language has typically not been consistent in transliteration methodology of Biblical proper names. Some of this stems from the fact that Hebrew is pronounced in a way that sometimes makes it difficult to transliterate into English with complete precision.

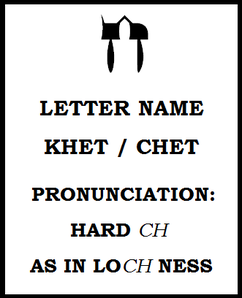

For instance, the Hebrew letter Khet /Chet is often transliterated as either an H or a CH in a name. Think of the Biblical name Hannah, which does not, in Hebrew, begin with the "H" sound as in hello, at all. Think also of the Biblical name Rachel, which does not, in Hebrew, possess the "ch" sound as in cherry, at all. The Hebrew letter attempting to be transliterated in those two names is not vocalized by the English letters H or CH. Rather, it is a guttural sound, made at the back of the throat, as a hard H, much like the ch in Loch Ness.

For instance, the Hebrew letter Khet /Chet is often transliterated as either an H or a CH in a name. Think of the Biblical name Hannah, which does not, in Hebrew, begin with the "H" sound as in hello, at all. Think also of the Biblical name Rachel, which does not, in Hebrew, possess the "ch" sound as in cherry, at all. The Hebrew letter attempting to be transliterated in those two names is not vocalized by the English letters H or CH. Rather, it is a guttural sound, made at the back of the throat, as a hard H, much like the ch in Loch Ness.

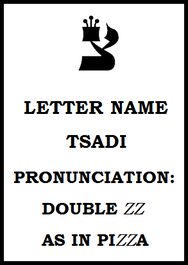

Another letter difficult to transliterate properly into English is the Hebrew letter Tsadi, which is often transliterated as a Z or as an S. Think of the Biblical name Zion, which does not, in the Hebrew, begin with the "Z" sound as in zipper, at all. Think also of the Biblical mountain name Salmon, which does not, in the Hebrew, begin with the "S" sound as in sell, at all. Rather, both names start with the letter Tsadi, which makes the sound of the double zz like in the word pizza.

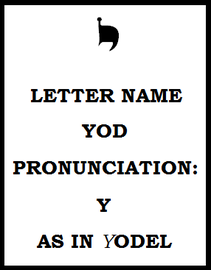

To add to the issue of the difficulty of properly transliterating proper names of people and places, the English is guilty of unnecessarily altering pronunciation of names that most certainly can be pronounced from Hebrew to English. Take, for example, the letter Yod. It is typically pronounced like a Y sound, as in yodel or yellow. This is seen in names like Yehoshaphat, or Yonathan, which are, respectively, altered when transliterated into English by turning the Y sound into a J sound, to render such results as Jehoshaphat and Jonathan. This is partly the reason why the Hebrew name for our Messiah – Yeshua – is now pronounced in modern English with the very poorly-preserved version of Jesus.

It is my desire to translate the Word in integrity, and a facet of that desire means presenting the names of people and places in as close-to-original form through transliteration into English. As a student of the Word, I feel it is best to honor what is preserved there above traditional forms of names, and because of this, passages shared in the studies I present containing the proper names of people and places will reflect the actual pronunciations in their Semitic forms.

QUESTION: Why do you use the Aramaic so often when you share verses from the New Testament? What about the Greek?

ANSWER: I have been in intensive study of the textual landscape of the New Testament for the greater part of my believing life. That study has taken the form of careful examination of the ancient languages in which we have extant manuscripts of to this day. The most prolific of those languages in which I have studied the New Testament have been the Greek and the Aramaic. While many very apt scholars promote the Greek manuscripts for study over the Aramaic, in my comparison between the two, I have found far more reasons to trust the Aramaic over the Greek when it comes to fine points of detail and preservation of what is assumed to be the actual words spoken or penned by the scribes. In my years of study, I have very painstakingly taken effort to compare the words of Greek manuscripts between themselves, and the words of Aramaic manuscripts between themselves, and then attempt to come to a conclusion on which appears more ancient and original. In all of that, from studying Greek manuscripts and fragments, to Aramaic codices and palimpsests, what has stood head and shoulders over them all as the most trustworthy candidate for the actual words of our Messiah and His early students strongly appears to me to be the Aramaic text known as the Eastern Peshitta. Such specific Eastern Peshitta codices as the Khabouris and the Mingana have especially proved helpful in coming to a personal conclusion on which Aramaic text is to be favored above other candidates such as the Curetonian, Old Syriac, Philoxenian, and Harklean. For that reason, the reader shall find throughout these studies presentations of the Aramaic text of the Eastern Peshitta that display various aspects of unique readings, word-plays, and highlights of readings that offer more depth, better explanations, or examples of where the Greek was poorly rendered from the Aramaic, in hopes to provide examples that will bolster the believer’s trust in the preserved transmission of the inspired text of the Word by the Spirit.

QUESTION: You have many studies that support keeping the Law of the Old Testament. Wasn’t that abolished by the Savior? Are you a Judaizer? Are you a Jew that believes in Jesus?

ANSWER: While I am not of Jewish ancestry, I do ascribe to observing as much of the Law (Torah) as is personally able and societally allowed. I do not believe that Messiah came to abolish what is commonly but erroneously called the "Old Testament," but to fill up the Word of the Holy One. Due to many passages in the Hebrew Scriptures that are prophetic in nature, and yet speak of the Law still being performed in a time yet to come, it is my belief that if it was in place before, and will be in place again at a future date, that it is illogical to believe that it is not still viable at this moment – to the extent that it can be still performed personally and societally. Based on this position, I approach the writings commonly called the New Testament with sure faith, and yet careful exegesis (explanation), so that I do my personal best to make sure my understanding of what the Spirit has preserved in the those pages is comprehended not in the light of traditional Church perspectives on the Law, which have themselves changed over the years, but rather, by the foundation of Hebrew Scripture and the lens of careful consideration for context to understand the meaning of whatever passage is being read. In doing this, I have come to the conclusion over the years that no passage in the New Testament actually speaks against the observance of the Law if done out of true faith in the Holy One and the Messiah.

With this understanding in place, I do not consider myself a Judaizer in any way, in that, under the context of the New Testament itself, a Judaizer was a Jewish person who advocated for the performance of religious traditions over and above the actual received words of Scripture themselves. In essence, a Judaizer was one who promoted their particular denomination’s traditions and views of how to behave in a way that superseded the importance of doing the commandments that are undeniably given by the Holy One. Consider this factor for perspective: the angst shown by Messiah towards the religious leaders of His day, and the same angst shown by Paul to the Judaizers of his day, was that the Word of the Law was being set aside to instead give preference to religious tradition. It would make no logical sense for the Messiah to lambast the religious leaders for setting aside the importance of observing the Law to instead focus on their traditions if He was actually about to abolish the Law Himself and allow for all kinds of new traditions to arise. It would make Him a huge hypocrite – a thought to which I cannot ascribe. Neither would it make any logical sense for Paul – after coming to faith in Yeshua – to continue to live a lifestyle of observance to the Law in the book of Acts (to the point of taking a vow that required animal sacrifice in the Temple, as seen in Acts 21), and then be interpreted by many in the Church as speaking against exactly that type of Law observance in his letters to different assemblies. He would likewise be a hypocrite. Thus, I use context to determine exactly what was being relayed in any given passage, so that I preserve the logical tapestry of the Word and do not promote the Church’s implied hypocrisy of Yeshua, Paul, and the other students of the Messiah.

While tradition is not in and of itself to be denigrated, when it is elevated above the inspired will for man of the Holy One, then it becomes something to be addressed and corrected. My position is that of total trust in the redemptive work of the Messiah for me. I do not believe that, in a life of observance of the Law and trust in the Messiah, that I can – by that observance – add anything to the beauty of the finished work that He alone performed. Rather, by observance of the Law, I am constantly reminded of my weakness before His righteousness, and am also allowing the Spirit to continue to work through the Word the life-long process of sanctification. This work of sanctification is evidence of the Spirit’s presence in my life, as well as a preparation of my mind and heart for participation in the Kingdom that is coming to this earth at the return of the Messiah Himself to rule as King over the nations, when the Law will again go forth from Zion in righteousness. Thus, my observance is the allowance of the Spirit to prepare me as He sees fit for whatever purpose I may be given as a citizen of that coming Kingdom, which is to be governed by the rule of the Law of the Holy One, under the authority of His one and only Son – Yeshua the Messiah – our only hope.

With this understanding in place, I do not consider myself a Judaizer in any way, in that, under the context of the New Testament itself, a Judaizer was a Jewish person who advocated for the performance of religious traditions over and above the actual received words of Scripture themselves. In essence, a Judaizer was one who promoted their particular denomination’s traditions and views of how to behave in a way that superseded the importance of doing the commandments that are undeniably given by the Holy One. Consider this factor for perspective: the angst shown by Messiah towards the religious leaders of His day, and the same angst shown by Paul to the Judaizers of his day, was that the Word of the Law was being set aside to instead give preference to religious tradition. It would make no logical sense for the Messiah to lambast the religious leaders for setting aside the importance of observing the Law to instead focus on their traditions if He was actually about to abolish the Law Himself and allow for all kinds of new traditions to arise. It would make Him a huge hypocrite – a thought to which I cannot ascribe. Neither would it make any logical sense for Paul – after coming to faith in Yeshua – to continue to live a lifestyle of observance to the Law in the book of Acts (to the point of taking a vow that required animal sacrifice in the Temple, as seen in Acts 21), and then be interpreted by many in the Church as speaking against exactly that type of Law observance in his letters to different assemblies. He would likewise be a hypocrite. Thus, I use context to determine exactly what was being relayed in any given passage, so that I preserve the logical tapestry of the Word and do not promote the Church’s implied hypocrisy of Yeshua, Paul, and the other students of the Messiah.

While tradition is not in and of itself to be denigrated, when it is elevated above the inspired will for man of the Holy One, then it becomes something to be addressed and corrected. My position is that of total trust in the redemptive work of the Messiah for me. I do not believe that, in a life of observance of the Law and trust in the Messiah, that I can – by that observance – add anything to the beauty of the finished work that He alone performed. Rather, by observance of the Law, I am constantly reminded of my weakness before His righteousness, and am also allowing the Spirit to continue to work through the Word the life-long process of sanctification. This work of sanctification is evidence of the Spirit’s presence in my life, as well as a preparation of my mind and heart for participation in the Kingdom that is coming to this earth at the return of the Messiah Himself to rule as King over the nations, when the Law will again go forth from Zion in righteousness. Thus, my observance is the allowance of the Spirit to prepare me as He sees fit for whatever purpose I may be given as a citizen of that coming Kingdom, which is to be governed by the rule of the Law of the Holy One, under the authority of His one and only Son – Yeshua the Messiah – our only hope.

QUESTION: What version of the Bible do you use for verses that you share?

ANSWER: Unless otherwise noted, all quotes from Scripture are taken straight from the Hebrew or Aramaic texts themselves by me. Years of study of the languages of the Word have brought about a desire to read freshly from those languages in my Bible reading time, and so, when it comes to presenting any given study, unless noted otherwise, I will draw straight from the text at hand to render a very literal English translation. I prefer literal translations if I am reading a translation, and my in my own translating of a passage, will do everything I can to present it as literally as possible, so that no personal opinion is coloring what the Spirit has preserved in His actual text. Learning the languages of the Word is a gift that every believer should seek to obtain, and one that will free you up from relying on man’s translations, which are sometimes not as straightforward as they could be. It is a gift that nobody can take from you, and one I encourage every believer to spend concerted effort in acquiring.

QUESTION: You use the Jewish Talmud in several of your studies. Do you believe it is authoritative in the way that those in Orthodox Judaism view it as the “Oral Law?”

ANSWER: My view on the Talmud, the Mishnah, the Midrashim, and other ancient extra-Biblical Jewish writings in general, is that they are valuable to the believer in specific ways. Firstly, they are excellent glimpses of the culture of Israel during the time surrounding the life of the Messiah. For that reason alone, the picture they portray is largely significant to the believer who is interested in gleaning a clearer context of cultural and societal matters recorded in the New Covenant text. These texts should not be viewed as more authoritative for believers in the Messiah, however, when it comes to information contained in them, since the content of the New Covenant writings records portraits of first-century Israel life under Roman rule that legitimately predates the passed-down information found in the Talmudic literature. Even The late Jewish scholar, Dr. Alan F. Segal, wrote in his book, Paul the Convert, “A commentary to the Mishnah should be written, using the New Testament as marginalia that demonstrates antiquity.” This sentiment speaks volumes, and is a view that must be maintained by the believer in Messiah when wading into the churning waters of ancient Jewish extra-Biblical writings. Most of what is written in the Mishnah and Gemara, and the Talmud proper, are points of view recalled from teachers to students – who themselves became teachers with students, and so on and so forth. It is not always first-hand anecdotes and perspectives of cultural and religious life in Israel, whereas the content of the New Covenant writings most demonstrably is from first-hand sources from the first century, which should take precedence in the formulation of our opinions on Scriptural matters.

That being said, generations of very studious scholars have their insights preserved here and there in the Talmud, showing how many spiritual matters were viewed, and how they were lived out in day-to-day life. Although the conclusions on some matters are clearly biased toward the perspective they promoted, if one uses the material cognizant of these possibilities, the words of these followers of the Most High can be very helpful and are complementary to the information preserved in the texts about the Messiah. The rabbis of the Talmud carefully deconstructed almost every aspect of the Torah, taking it apart in near clinical dissection, in order to define the often-fine line between obedience and disobedience. For this, they are to be commended. Many of the excerpts I present in my studies that come from various tractates of the Talmud are done in order to show that a particular idea being presented is not new, but anciently viewed as such in Judaism, and in that way, one can see the Spirit at work in the Jewish people in subtle ways, sowing faith in their hearts for the Messiah who was to come, or, depending on the time of the writing of the excerpt, who had already come. Other passages shared are done so to further elaborate upon ideas already contained in the Word that serve to provide a more complete portrait of what is being taught in the New Covenant.

While I use passages from the extra-Biblical Jewish writings to prove particular points or single-out instances of interest, I do not hold that the texts are inspired in the same way that I hold the texts of the Hebrew Scriptures and the Aramaic New Covenant to be authoritative spiritual works overseen completely by the Spirit. I do believe there are shining gems of merit here and there in the Talmudic literature, but I do not hold the texts or the assumed authority of the rabbis in it to be of a spiritually-binding nature. Each decree and opinion in the Talmudic texts must be assessed on a case-by-case basis for the most accurate analysis of its content.

In spending much time reading the actual texts themselves in effort to learn what is really taught in it, I have seen the unsightly issues that are present there, and they are real and should not be ignored. It is not my intent to whitewash the problematic issues of the Talmud just by sharing in my studies the points of interest that are of relevance to what I am teaching. Like any writing of man’s opinion on spiritual matters, there will be places where it misses the mark. Similarly, it displays also limitations of the knowledge of the day in superstition and medical matters. There are ample passages of which one could be critical, and yet such critical presentations of the Talmudic writings does not equal anti-Semitism, but rather, rational, honest address of some of the absurdity that does exist in it, and in doing so, we are able to sincerely approach it with the proper understanding: it is not to be taken wholly as binding spiritual authority for the believer in Messiah, but as a testament to the views of Judaism about all manner of things spiritual and cultural. Where it aligns with His will, allow us to use it as needed, and where it does not, let us also use it as needed to correct those who ascribe to it improper authority. I provide here for the interested reader selected passages that display content that cannot be rightly held to be spiritually or factually accurate by any logical standards.

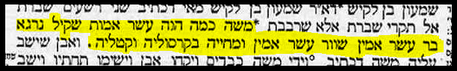

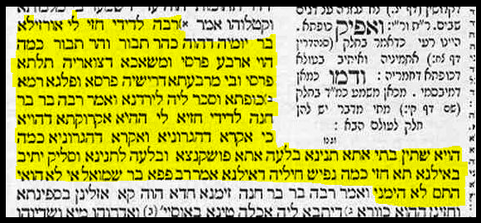

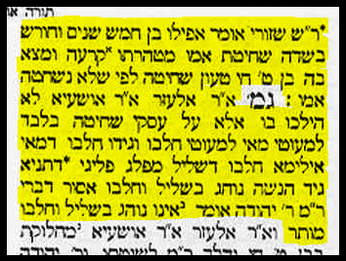

While there are opinions on many matters in it, some asserted facts in the Talmudic texts are simply crazy to believe. This one, from tractate Berachot 54b, does well to illustrate the point by mentioning a wild assertion about the stature of Moses.

That being said, generations of very studious scholars have their insights preserved here and there in the Talmud, showing how many spiritual matters were viewed, and how they were lived out in day-to-day life. Although the conclusions on some matters are clearly biased toward the perspective they promoted, if one uses the material cognizant of these possibilities, the words of these followers of the Most High can be very helpful and are complementary to the information preserved in the texts about the Messiah. The rabbis of the Talmud carefully deconstructed almost every aspect of the Torah, taking it apart in near clinical dissection, in order to define the often-fine line between obedience and disobedience. For this, they are to be commended. Many of the excerpts I present in my studies that come from various tractates of the Talmud are done in order to show that a particular idea being presented is not new, but anciently viewed as such in Judaism, and in that way, one can see the Spirit at work in the Jewish people in subtle ways, sowing faith in their hearts for the Messiah who was to come, or, depending on the time of the writing of the excerpt, who had already come. Other passages shared are done so to further elaborate upon ideas already contained in the Word that serve to provide a more complete portrait of what is being taught in the New Covenant.

While I use passages from the extra-Biblical Jewish writings to prove particular points or single-out instances of interest, I do not hold that the texts are inspired in the same way that I hold the texts of the Hebrew Scriptures and the Aramaic New Covenant to be authoritative spiritual works overseen completely by the Spirit. I do believe there are shining gems of merit here and there in the Talmudic literature, but I do not hold the texts or the assumed authority of the rabbis in it to be of a spiritually-binding nature. Each decree and opinion in the Talmudic texts must be assessed on a case-by-case basis for the most accurate analysis of its content.

In spending much time reading the actual texts themselves in effort to learn what is really taught in it, I have seen the unsightly issues that are present there, and they are real and should not be ignored. It is not my intent to whitewash the problematic issues of the Talmud just by sharing in my studies the points of interest that are of relevance to what I am teaching. Like any writing of man’s opinion on spiritual matters, there will be places where it misses the mark. Similarly, it displays also limitations of the knowledge of the day in superstition and medical matters. There are ample passages of which one could be critical, and yet such critical presentations of the Talmudic writings does not equal anti-Semitism, but rather, rational, honest address of some of the absurdity that does exist in it, and in doing so, we are able to sincerely approach it with the proper understanding: it is not to be taken wholly as binding spiritual authority for the believer in Messiah, but as a testament to the views of Judaism about all manner of things spiritual and cultural. Where it aligns with His will, allow us to use it as needed, and where it does not, let us also use it as needed to correct those who ascribe to it improper authority. I provide here for the interested reader selected passages that display content that cannot be rightly held to be spiritually or factually accurate by any logical standards.

While there are opinions on many matters in it, some asserted facts in the Talmudic texts are simply crazy to believe. This one, from tractate Berachot 54b, does well to illustrate the point by mentioning a wild assertion about the stature of Moses.

Mosheh was ten cubits tall. He took an axe ten cubits long, leapt ten cubits into the air, and smote him [Og, a giant of Scripture] on his ankle and killed him.

While Scripture does speak of people of gigantic stature in certain areas, the idea that a giant of 15 feet (an incredible height, and one that is at the upper end of the heights of giants mentioned in the Word) who, upon leaping ten cubits into the air, only reached the ankles of Og, is simply unbelievable.

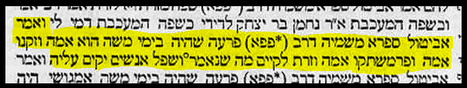

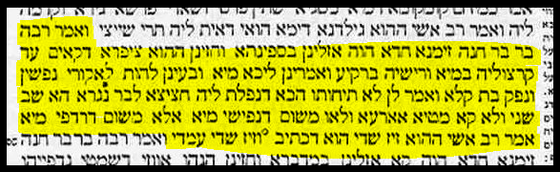

Apparently, the Talmud would also have us believe quite a dichotomy existed between the physical size of Moses and that of Pharaoh, as we learn elsewhere in tractate Moed Katan 18a that the Pharaoh of the exodus was a very, very small man.

Apparently, the Talmud would also have us believe quite a dichotomy existed between the physical size of Moses and that of Pharaoh, as we learn elsewhere in tractate Moed Katan 18a that the Pharaoh of the exodus was a very, very small man.

And Abitul the hair-dresser, said of Rab Papa: “Pharaoh who was in the days of Mosheh, was a cubit [in height], and [with] a beard a cubit long, and his bundle of hair a cubit and a span, establishing what is said: ‘And He sets up lowly men over it [the worldly kingdoms] [Daniel 4:14].’”

The idea that Pharaoh was of such diminutive stature is difficult to accept. A cubit is generally viewed to be the length of a man's forearm, from elbow to fingertip. This would be in the range of eighteen to twenty-something inches - a size that would be astonishingly small for a human being to maintain as a viable organism.

The Talmud seems to accept that not only men could be of bizarre size, but that it was common for animals to also reach almost unfathomable growth, as tractate Bava Bathra 73b shows us in unequivocal detail.

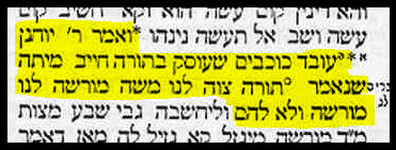

Rabbah said, “I saw an antelope, a day old, who was as [large as] Mount Tabor. And Mount Tabor is how tall? More than fourteen miles. And the length of its neck was more than eleven miles. And the resting spot of its head was five and half miles. It defecated and stopped up the Yurdana [ Jordan river].” And Rabbah, son of Bar Hana [continued to] say, “I saw a frog as the size of Fort Hagronia. And the Fort of Hagronia is how tall? [As] sixty houses. A serpent came and swallowed it. A raven came and swallowed the serpent, and ascended to sit on a tree. Come see the how tall was the body of the tree!” Rab Papa, son of Shemu’El, said, “Oh, had I not been present, I would not have believed it!”

One might easily brush off the words of Rabbah as a truly "tall" tale, but then the added words of Rab Papa are inserted at the end in attempt to ward off the scoffers - as if such would now hold any real merit! The text of the same folio goes on to record yet another "tale to astonish" by the same rabbi:

And Rabbah, son of Bar Hana [continued to] say, “See, we were travelling on a boat and we saw a bird standing up to its ankles in the water, and its head was in the firmament. And we were saying, ‘There’s no water [of any depth].’ And we wanted to go down to cool our bodies, and a daughter of a voice [a heavenly message] went out, and said, ‘Do not go down, for the ax of a carpenter fell seven years [prior], and it hasn’t arrived at the bottom. And this is so not [only because] of the body of the water, but it is so [because] of the swiftness of the water.’” Rab Ashi said, “That was a Ziz-Sadai, for it is written: ‘And Ziz-Sadai is with Me [Psalm 50:11].’”

The phrase ZIZ-SADAI translates into "creature of the field," and since the Biblical verse says that such is "with Me," the interpretation of this bird creature is that it is of such special size that it can stand on earth and its head reaches into the heaven where the Holy One dwells. This tractate continues such stories through the folio and the one after it, recording absolutely unbelievable sizes of creatures. I have shared here only two to give the reader an idea of the oddities preserved in the text which the reader is supposed to accept as real.

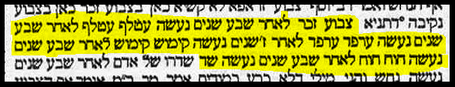

The Talmudic text has a lot to say about strange creatures that could fill a cryptozoologist's dream, however, there is one passage in particular, in Bava Kama 16a, that is arguably the most extreme case of weirdness regarding animals.

The Talmudic text has a lot to say about strange creatures that could fill a cryptozoologist's dream, however, there is one passage in particular, in Bava Kama 16a, that is arguably the most extreme case of weirdness regarding animals.

The male hyena, after seven years, becomes a bat; the bat, after seven years, becomes a vampire; the vampire, after seven years, becomes a nettle; the nettle, after seven years, becomes a thorn; the thorn, after seven years, becomes a demon.

The reader can see that no quaint micro-evolution is being proposed here, but rather, full blown punctuated equilibrium on a scale never even suggested by proponents of macro-evolution - out-and-out transmogrification from known physical creatures finally into a dark spiritual entity! The idea is as preposterous as it can get, and yet these were concepts believed by the rabbis to have been fact in their day.

The concept of demons and their interaction with human affairs is not one to be down-played, as the reality of the spiritual world is valid, and yet the Talmud has many places where demonic activity is described that makes no logical sense, even with the understanding that we are dealing with a supernatural subject matter, as tractate Shabbat 151b shows so well.

The concept of demons and their interaction with human affairs is not one to be down-played, as the reality of the spiritual world is valid, and yet the Talmud has many places where demonic activity is described that makes no logical sense, even with the understanding that we are dealing with a supernatural subject matter, as tractate Shabbat 151b shows so well.

Rabbi Khanina said, “It is forbidden to sleep in a house alone, for all who sleep in a house alone are seized by Lilith.”

The reference to Lilith is an ancient Jewish concept, having the inkling of its origins from actual Scripture in its one appearance from Isaiah 34:14, where it is the Hebrew word behind which the English renders variously as "screech owl," or "night creature," or something along that line. The word is essentially the feminine word for "night," which is strange in itself, and appears in a list of wild animals, so that there is no direct English translation to describe what is being referenced by the prophet. The Talmudic concept of Lilith is not as an animal, as one would expect would be derived from the context of Isaiah 34:14, but rather, in the crazy notion preserved in the Dead Sea Scroll fragment 4Q510-511, where Lilith is listed along with other demonic spirits that offend and entrap mankind. She is further developed in Jewish folklore in various midrashic texts I shall feign to quote from here. As it stands, the text from Shabbat 151b is saying that a person cannot sleep alone for fear of being assaulted by a demon they explain to be the Lilith of the Bible!

The decrees in the Talmud given to keep people safe from demons are many and varied. An especially stringent one is found in tractate Sanhedrin 44a, producing a prohibition that seems entirely untenable.

The decrees in the Talmud given to keep people safe from demons are many and varied. An especially stringent one is found in tractate Sanhedrin 44a, producing a prohibition that seems entirely untenable.

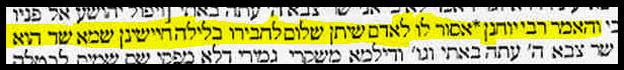

And Rabbi Yokhanan said, “It is forbidden for a man to give a ‘Shalom’ to his companion at night, for fear he is a demon.”

The injunction laid forth here is that a person cannot give a greeting to someone they meet in public after the sun has set. The Hebrew word "Shalom" is used in the same way that English speakers say "Hello," or "Good Evening," or similar salutations. The fear that someone who is met after sundown is secretly a demon masquerading as a human presented such a reality to the Talmudic rabbis that they forbade their students from even the slightest of human interaction when done under the veil of night in a public place.

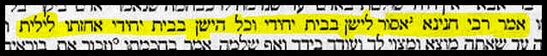

It is my hope that the reader can see in these examples the absurdity that exists in some passages of the Talmud. While one might shake a head and sigh at accounts such as these, and rightfully so, there exist others of a more significant weight, whose gravity comes to bear on how people are treated and viewed based on what they do or what they are that cannot be helped. For instance, in tractate Pesachim 111a, the warning is given not to allow certain animals to pass between two men in public. The caution goes so far as to include a woman in the list - and for a seriously astounding reason!

It is my hope that the reader can see in these examples the absurdity that exists in some passages of the Talmud. While one might shake a head and sigh at accounts such as these, and rightfully so, there exist others of a more significant weight, whose gravity comes to bear on how people are treated and viewed based on what they do or what they are that cannot be helped. For instance, in tractate Pesachim 111a, the warning is given not to allow certain animals to pass between two men in public. The caution goes so far as to include a woman in the list - and for a seriously astounding reason!

If a menstruating woman passes between two [men], if it is at the start of her period she will kill one of them; if it is at the end of her period she will make strife between them.

It is no debate that the Torah prescribes certain limitations upon women in their monthly cycles, and the reasoning for those divine prohibitions are wise and spiritual. However, the recorded warning given here in the Talmud is a far cry from the inspired and binding commandments found in Scripture concerning personal hygiene and what can and cannot be done during those times. The idea that a woman in her monthly cycle could bring untimely death to a man just by walking in proximity to him, or that she could evoke strife between men by doing so - all based on whether or not she has just begun or is near to stopping - is absolutely not found in the Word. To be treated as dangerous just for the possibility that a woman is experiencing her menses is entirely uncalled-for. The Torah provides no commandment forbidding a woman on her period from going out into the public. However, the Talmud places upon her a malevolent nature when she does.

Similarly to the above view, tractate Sanhedrin 59a records that the Gentile who actively observes the Torah, without becoming a verified "convert," is worthy of death!

Similarly to the above view, tractate Sanhedrin 59a records that the Gentile who actively observes the Torah, without becoming a verified "convert," is worthy of death!

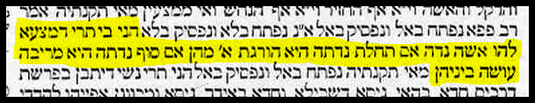

And Rav Yokhanan said: “‘Heathens’ who are active in Torah deserve death, for it is written: ‘Mosheh commanded for us a Torah [for an] inheritance [Deuteronomy 33:4];’ [It is] for us an inheritance, and not for them.”

In this unfortunate passage, the text tells us that the Torah belongs only to the Hebrew people, and for someone whom they view as a heathen to engage in it is a crime worthy of death! The term used to refer to the "heathens" is used in the Hebrew Scriptures in one place to refer to those who worship a "Godhead," and although we cannot be certain the term as used here in the Talmud is in precise reference to believers in the Messiah Yeshua, it is worth noting that the term is used. It is disturbing to think that even a valid heathen would be under the death penalty for their crime of marginal Torah-observance, instead of viewing them rather as ripe for abandoning their remaining idolatries and embracing the truth wholeheartedly.

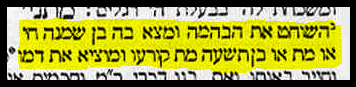

Another rather disturbing text in the Talmud is that regarding a very specific situation regarding the offspring of a kosher cow, ewe, or doe. In tractate Chullin 74a, the text speaks of an astounding allowance that must be carefully read to be appreciated as extreme.

Another rather disturbing text in the Talmud is that regarding a very specific situation regarding the offspring of a kosher cow, ewe, or doe. In tractate Chullin 74a, the text speaks of an astounding allowance that must be carefully read to be appreciated as extreme.

[If a man] slaughters an animal and found in her a son of eight [months], living or dead, or a son of nine [months], he only needs to tear it open and let come forth its blood.

The text thus far may not be so shocking, but let us continue on into Chullin 74b, the very next folio of the tractate, which begins with a further detail of the situation.

Rabbi Shimon Shezuri said, “Even if [it is a] son of five years, and plowing in a field, the slaughter of its mother makes it pure. [If] he tears her open and finds in her a son of nine [months] alive, it is required to be slaughtered, for its mother is not [yet] slaughtered.” Rabbi El’azar said in the name of Rabbi Oshaia, “They argued about it but only dealing [with the] slaughtering. This excludes what? [It] excludes the fat and the nerve. What is meant of ‘fat?’ Of the fetus? [Is there not] a division regarding it? For there is a teaching: The sciatic nerve applies to a fetus, and its fat is prohibited – [such are] the words of Rabbi Meir." Rabbi Y’hudah says, “It does not apply to the fetus, and its fat is permitted.”

If the reader at this point needs any clarification of what is going on, the answer is that a very technical discussion is unfolding in the tractate concerning what happens when one slaughters a female animal fit for food, and finds in it a living (or dead) fetus. The discourse involves how the fetus is to be viewed, insomuch as how it can be utilized as food. Does it need its own personal kosher slaughter, or should the kosher slaughter of the mother be reckoned as its kosher slaughter, for the life of the mother determined the life of the fetus? The answer they arrive at is that the slaughter of the mother removes any need for the further kosher slaughter of the fetus. Because of that, it need only have the blood drained from it - however one sees fit to do so, since it is not in need of undergoing proper slaughter techniques.

It is additionally discussed in the above passage if the sciatic nerve and the organ fat that is prohibited from being consumed by commandment of the Torah is thus allowed to be eaten on such an animal. Although there is initial dispute as to what is the right course of action, the final word is that both Torah-prohibitions of organ fat and sciatic nerve are no longer an obligation, and the entire animal's body is acceptable for food - the Torah's prohibition made null.

There are further ramifications to this decree, as in Rabbi Meir Simcha’s much-lauded work, Meshech Chochma, in the commentary to Genesis 18:8, the explanation for the serving of dairy and meat together [prohibited otherwise not by Torah, but by rabbinical decree] to the three men who visited Abraham's tent is that Abraham served his guests dairy products from this specific type of an animal, and as such, it was not considered to actually be dairy at all, and so could be mixed with meat with no further regard to conflict. The peculiar status of this type of animal, known popularly in Judaism's halakhic discussion as a ben pequah, is that the Biblical prohibition against eating the sciatic nerve does not apply, nor does the Biblical prohibition of eating the fat surrounding the organs – so that an Orthodox Jewish person is allowed to break Torah and eat both if the animal meets the qualifications given in the Talmud.

The usage of such an animal gets even crazier, in that the mating of two ben pequah animals extends the same halakhic allowance to their offspring, so that entire herds of ben pequah are able to be brought into existence, essentially creating a new line of meat / milk that does not conform to either Biblical or rabbinic prohibitions. It is spoken of in Orthodox Jewish history as a viable method for consuming flesh and milk, and yet was discontinued for centuries, until just very recently, where the restoration of the practice in Australia has been the subject of much controversy in Judaism – with rabbinical opinions both praising it and wary of it, for such ben pequah cattle cannot, for strict halakhic reasons, ever come in contact with normal cattle.

It is additionally discussed in the above passage if the sciatic nerve and the organ fat that is prohibited from being consumed by commandment of the Torah is thus allowed to be eaten on such an animal. Although there is initial dispute as to what is the right course of action, the final word is that both Torah-prohibitions of organ fat and sciatic nerve are no longer an obligation, and the entire animal's body is acceptable for food - the Torah's prohibition made null.

There are further ramifications to this decree, as in Rabbi Meir Simcha’s much-lauded work, Meshech Chochma, in the commentary to Genesis 18:8, the explanation for the serving of dairy and meat together [prohibited otherwise not by Torah, but by rabbinical decree] to the three men who visited Abraham's tent is that Abraham served his guests dairy products from this specific type of an animal, and as such, it was not considered to actually be dairy at all, and so could be mixed with meat with no further regard to conflict. The peculiar status of this type of animal, known popularly in Judaism's halakhic discussion as a ben pequah, is that the Biblical prohibition against eating the sciatic nerve does not apply, nor does the Biblical prohibition of eating the fat surrounding the organs – so that an Orthodox Jewish person is allowed to break Torah and eat both if the animal meets the qualifications given in the Talmud.

The usage of such an animal gets even crazier, in that the mating of two ben pequah animals extends the same halakhic allowance to their offspring, so that entire herds of ben pequah are able to be brought into existence, essentially creating a new line of meat / milk that does not conform to either Biblical or rabbinic prohibitions. It is spoken of in Orthodox Jewish history as a viable method for consuming flesh and milk, and yet was discontinued for centuries, until just very recently, where the restoration of the practice in Australia has been the subject of much controversy in Judaism – with rabbinical opinions both praising it and wary of it, for such ben pequah cattle cannot, for strict halakhic reasons, ever come in contact with normal cattle.

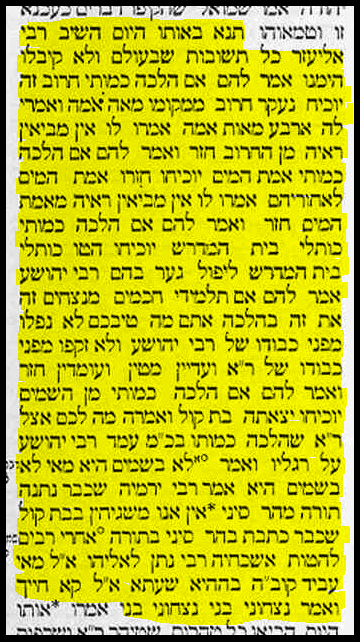

I wish to share one further example from the Talmud which showcases the gravest type of problem promoted in its pages. In Bava Metzia 59a, and taking up most of 59b, a discussion is presented about a dispute between rabbis concerning if an oven constructed in a peculiar manner could be subject to ritual impurity. The idea initially presented concerns an oven that is made of distinctly separate parts, and with each piece being separated by a layer of sand, so that no two pieces actually ever touch. Therefore, the dispute recorded is that a certain rabbi – Rabbi El’azar, said that an oven made in such a way would not assume ritual impurity because it was not “really” a receptacle designated by Torah that could become ritually impure. While his opinion may seem like a technicality, and is the type of conclusion often arrived-at through clinical dissection of the Torah's commandments, we read that the majority of the other rabbis, in a surprise turn of events, disagree with his ruling! The story picks up fully in Bava Metzia 59b from that point and is shared here for the reader to see how insane it can get.

It has been taught: On that day Rabbi El’azar returned every response that is in the world, and they did not receive them. He said to them, “If the ruling is with me, let this carob tree decide it!” Then the carob was uprooted from its place one hundred cubits – and others [say] four hundred cubits. They said to him, “Nothing can be brought to sight from the carob!” And again, he said to them, “If the ruling is with me, let the stream of water decide it!” Again, the stream of water flowed backwards. They said to him, “Nothing can be brought to sight from a stream of water!” And again, he said to them, “If the ruling is with me, let the walls of the house of study decide it!” Then began the walls of the house of study to fall, but Rabbi Y’hoshua scolded them, saying to them, “If disciples of the wise are involved [with] this [or] this with a ruling, what have you to interfere?” Thus, they did not fall for the honor of Rabbi Y’hoshua, and they did not straighten for the honor of Rabbi El’azar, and they stand still inclined. And again, he said to them, “If the ruling is with me, let it be decided from Heaven!” [Then] came forth a daughter of a voice [a heavenly message], and said to them, “Why refuse Rabbi El’azar? The ruling is with him in all matters!” [But] Rabbi Y’hoshua stood upon his feet and said, “It is not in heaven! [Deuteronomy 30:12]” Why [did he say] “It is not in heaven?” Rabbi YirmeYah said, “Already has the Torah been given from Mount Sinai; in the Torah [it says] “...after the multitudes [literally: rabbim] turn aside [Exodus 23:2].” And [later] Rabbi Natan met EliYahu [the prophet], and he asked him, “What did the Holy One, Blessed be He, do in that hour?” He laughed, and said, “My sons have triumphed [over] Me! My sons have triumphed [over] Me!”

The reader can see the amazing account relayed in the Talmud for us all: the dispute between whom is right is incredibly heated – to the point that miracles are called upon to prove the case of Rabbi El’azar. Each request for a miracle he makes is granted, and each miracle is then disregarded impudently by his opponents, until he goes so far as to ask for direct confirmation of his view from heaven itself. A heavenly voice is recorded to have called out in blatant favor of Rabbi El’azar’s position, to which an astonishing answer is given: the Torah is no longer in the rule of heaven, but has been given to the rabbis, and their authority is now binding. The Torah itself is actually quoted twice in attempt to make their case – the first quoting a passage that declares contextually that the Torah is easy to do – not that the authority of the Torah is limited only to rabbis on earth. They take the meaning entirely out of context. The second passage quoted is actually telling us not to follow the multitudes into perverse rules – not that men are to follow after the rabbis. Interestingly, the actual wording of the second passage in its Hebrew form given here in the Talmud, as it is brought up out of context by the rabbi, suggests to the reader that people are to follow after the rabbis even when in blatant error!

The Talmudic text quoted here then has another rabbi who just happens to meet Elijah the prophet (yes, after he had ascended to heaven), and asked the heavenly visitor what the Holy One thought of that dispute and its outcome. The entire matter is said to have been laughed off by the Most High, when in truth, the conclusion is as criminal a wresting of divine authority as the Enemy bringing man into rebellion in the Garden.

What is not quoted directly here from the tractate, but is worth noting, is that the aftermath of the dispute is further given in the Talmud, wherein the rulings of Rabbi El’azar are condemned by his opponents, and he is officially excommunicated from his peers. This is a huge decision, for elsewhere in the Talmud, Rabbi El'azar's positions are overwhelmingly agreed to be correct. That they disdained his staunch position against their combined perspective is evidenced in the way they vilify his formerly-viewed righteous opinions on spiritual matters. It goes on to reveal that the spurned Rabbi El’azar’s mourning over his fellow rabbi’s stance against him becomes so vocal in his prayers that it brings about a response of great divine calamity to the world - even though the Holy One is said to have laughed at what coup they were able to orchestrate together. His lament to heaven is so severe, and so surprisingly answered - given the Most High's original response - that the text states it ends up resulting in the death of the much-revered Rabban Gamaliel – who was the head of the Sanhedrin – the body in opposition to Rabbi El’azar’s original view.

I have endeavored to display in this admittedly lengthy response pertinent passages in context that showcase why the Talmud, although used to some valid reason by believers in Messiah, should by no means be accepted as an authoritative “Oral Law” like we accept the received inspired text of the Hebrew Scripture. The student of the Bible and Hebrew culture has much to learn from the Talmudic texts that can profit one’s studies in many ways. However, it is revealed with careful attention that it is yet essentially still a writing of man’s views on life both secular and spiritual, and as such, needs be utilized with care in separating the gold from the dross.

It has been taught: On that day Rabbi El’azar returned every response that is in the world, and they did not receive them. He said to them, “If the ruling is with me, let this carob tree decide it!” Then the carob was uprooted from its place one hundred cubits – and others [say] four hundred cubits. They said to him, “Nothing can be brought to sight from the carob!” And again, he said to them, “If the ruling is with me, let the stream of water decide it!” Again, the stream of water flowed backwards. They said to him, “Nothing can be brought to sight from a stream of water!” And again, he said to them, “If the ruling is with me, let the walls of the house of study decide it!” Then began the walls of the house of study to fall, but Rabbi Y’hoshua scolded them, saying to them, “If disciples of the wise are involved [with] this [or] this with a ruling, what have you to interfere?” Thus, they did not fall for the honor of Rabbi Y’hoshua, and they did not straighten for the honor of Rabbi El’azar, and they stand still inclined. And again, he said to them, “If the ruling is with me, let it be decided from Heaven!” [Then] came forth a daughter of a voice [a heavenly message], and said to them, “Why refuse Rabbi El’azar? The ruling is with him in all matters!” [But] Rabbi Y’hoshua stood upon his feet and said, “It is not in heaven! [Deuteronomy 30:12]” Why [did he say] “It is not in heaven?” Rabbi YirmeYah said, “Already has the Torah been given from Mount Sinai; in the Torah [it says] “...after the multitudes [literally: rabbim] turn aside [Exodus 23:2].” And [later] Rabbi Natan met EliYahu [the prophet], and he asked him, “What did the Holy One, Blessed be He, do in that hour?” He laughed, and said, “My sons have triumphed [over] Me! My sons have triumphed [over] Me!”

The reader can see the amazing account relayed in the Talmud for us all: the dispute between whom is right is incredibly heated – to the point that miracles are called upon to prove the case of Rabbi El’azar. Each request for a miracle he makes is granted, and each miracle is then disregarded impudently by his opponents, until he goes so far as to ask for direct confirmation of his view from heaven itself. A heavenly voice is recorded to have called out in blatant favor of Rabbi El’azar’s position, to which an astonishing answer is given: the Torah is no longer in the rule of heaven, but has been given to the rabbis, and their authority is now binding. The Torah itself is actually quoted twice in attempt to make their case – the first quoting a passage that declares contextually that the Torah is easy to do – not that the authority of the Torah is limited only to rabbis on earth. They take the meaning entirely out of context. The second passage quoted is actually telling us not to follow the multitudes into perverse rules – not that men are to follow after the rabbis. Interestingly, the actual wording of the second passage in its Hebrew form given here in the Talmud, as it is brought up out of context by the rabbi, suggests to the reader that people are to follow after the rabbis even when in blatant error!

The Talmudic text quoted here then has another rabbi who just happens to meet Elijah the prophet (yes, after he had ascended to heaven), and asked the heavenly visitor what the Holy One thought of that dispute and its outcome. The entire matter is said to have been laughed off by the Most High, when in truth, the conclusion is as criminal a wresting of divine authority as the Enemy bringing man into rebellion in the Garden.

What is not quoted directly here from the tractate, but is worth noting, is that the aftermath of the dispute is further given in the Talmud, wherein the rulings of Rabbi El’azar are condemned by his opponents, and he is officially excommunicated from his peers. This is a huge decision, for elsewhere in the Talmud, Rabbi El'azar's positions are overwhelmingly agreed to be correct. That they disdained his staunch position against their combined perspective is evidenced in the way they vilify his formerly-viewed righteous opinions on spiritual matters. It goes on to reveal that the spurned Rabbi El’azar’s mourning over his fellow rabbi’s stance against him becomes so vocal in his prayers that it brings about a response of great divine calamity to the world - even though the Holy One is said to have laughed at what coup they were able to orchestrate together. His lament to heaven is so severe, and so surprisingly answered - given the Most High's original response - that the text states it ends up resulting in the death of the much-revered Rabban Gamaliel – who was the head of the Sanhedrin – the body in opposition to Rabbi El’azar’s original view.

I have endeavored to display in this admittedly lengthy response pertinent passages in context that showcase why the Talmud, although used to some valid reason by believers in Messiah, should by no means be accepted as an authoritative “Oral Law” like we accept the received inspired text of the Hebrew Scripture. The student of the Bible and Hebrew culture has much to learn from the Talmudic texts that can profit one’s studies in many ways. However, it is revealed with careful attention that it is yet essentially still a writing of man’s views on life both secular and spiritual, and as such, needs be utilized with care in separating the gold from the dross.

QUESTION: I've heard that Hanukkah was heavily influenced by the pagan festival called Saturnalia. What is the truth?

ANSWER: The answer is quite simply: "Chanukah is not influenced by Saturnalia." If you would like the historical factors that allow such a statement to be made so definitively, read on to the meat of my reply.

The past several years I have received inquiries from believers asking about this or that detail of Chanukah. Among them has been information proposing that the festival of Chanukah is a perverse mixing of the holy with the profane, and adding-to of the Word of the Most High. The majority assert that the ancient celebration of Saturnalia has influenced the observance of Chanukah to an irredeemable point. While I appreciate the zeal and care of every believer concerned about keeping their walk with our Creator pure and free from the stain of evil, I felt impressed to address these assertions with something that, unfortunately, so many teachings that proposing Saturnalia influenced and tainted Chanukah lack: historical evidence of what Saturnalia truly entailed. The response that follows treats the matter as bluntly as possible, dissecting the issue with blades of logic that are typically absent when teaching that Chanukah is a perverted Jewish form of Saturnalia. I hope the evidences provided herein will aid the questioning or intrigued believer to see the facts of the historical side of things, and come away knowing that the proposed influences of paganism upon Chanukah are startlingly absent.

ROME’S SATURNALIA INFLUENCING CHANUKAH IS AN ANACHRONISM

The first issue needing clarity is the assertion that Saturnalia’s customs heavily influenced the traditions placed upon the festival of Chanukah. The events of Chanukah, the rededication of the Temple and the resulting new traditions that came with it all occurred in the second century BCE, beginning on 175 BCE. What manner of role did Rome’s Saturnalia exert on the culture of Israel in the second century BCE? Seeing as how they did not enter the territory of Israel until 63 BCE from the northern land of Syria, whom they had only annexed the year prior, in 64 BCE, and that only because they were invited to help settle a political dispute among two ruling brothers, it is doubtful their influence upon the culture was even felt before that time in any meaningful manner.

Knowing the dates of when these events occurred quickly takes the life out of the assertion that Saturnalia heavily influenced the formation of Chanukah traditions, for those traditions were already established for over a century by the time Rome entered the land in a very conservative presence, at that. This shows that those who are teaching this are promoting an anachronistic view on the customs of Chanukah: Saturnalia was not encountered by the Jewish populace until over a century after Chanukah’s well-known traditions had been established, so it is utterly impossible for Saturnalia to have had a role in the formation of Chanukah customs. If Saturnalia had already enjoyed a presence among the people of Israel, then there would be something of merit in the possibility, but the texts of 1st and 2nd Maccabees had already been written by then, and it is quite possible the text of Megillat Benei Chashmonai had also already been written by this point, both containing information of the history and the traditions associated with the festival of Chanukah.

Knowing the dates of when these events occurred quickly takes the life out of the assertion that Saturnalia heavily influenced the formation of Chanukah traditions, for those traditions were already established for over a century by the time Rome entered the land in a very conservative presence, at that. This shows that those who are teaching this are promoting an anachronistic view on the customs of Chanukah: Saturnalia was not encountered by the Jewish populace until over a century after Chanukah’s well-known traditions had been established, so it is utterly impossible for Saturnalia to have had a role in the formation of Chanukah customs. If Saturnalia had already enjoyed a presence among the people of Israel, then there would be something of merit in the possibility, but the texts of 1st and 2nd Maccabees had already been written by then, and it is quite possible the text of Megillat Benei Chashmonai had also already been written by this point, both containing information of the history and the traditions associated with the festival of Chanukah.

COMPARING THE DETAILS

One of the common assertions found in writings online suggesting a link between Chanukah and Saturnalia is that the customs of Saturnalia heavily influenced the ones concerning Chanukah. Many different “customs” of Saturnalia are described when one reads such writings proposing a corrupted link. Anything can be written online today and called truth, but what matters is evidence that such observances did occur. The historical records that preserve how Saturnalia was observed in the Roman empire are what must be resorted to show the reality of the situation.

The texts of ancient Roman writers shed light on this often-misrepresented area of Saturnalia.

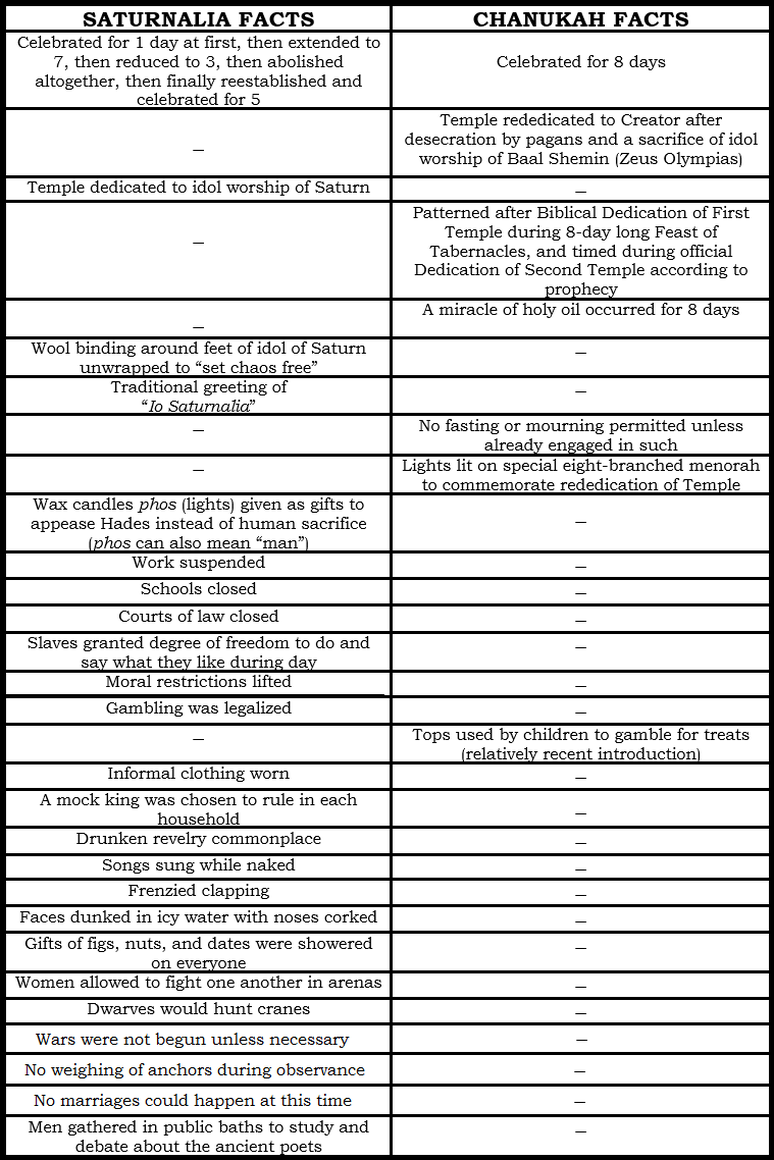

The pagan festival was quite popular in Rome, and for that, there is significant writing of how it was observed. The Roman writers made mention of several different practices. Examining the old texts allows us to see the actual customs that were performed, and not engage in the promulgation of false information as to what was done in an effort to link something pagan to something pure. This list shows customs mentioned all throughout ancient Roman texts, and the comparison to the customs of Chanukah can be then seen, as described in the ancient Jewish texts.

The texts of ancient Roman writers shed light on this often-misrepresented area of Saturnalia.

The pagan festival was quite popular in Rome, and for that, there is significant writing of how it was observed. The Roman writers made mention of several different practices. Examining the old texts allows us to see the actual customs that were performed, and not engage in the promulgation of false information as to what was done in an effort to link something pagan to something pure. This list shows customs mentioned all throughout ancient Roman texts, and the comparison to the customs of Chanukah can be then seen, as described in the ancient Jewish texts.

The reader can readily see that there is no direct overlapping between Chanukah and Saturnalia. The pagan feast has no bearing on the customs surrounding the rededication of the Temple in Jerusalem. Those espousing links are here shown to be suggesting non-existent parallels. The customs of Chanukah are wholly separate from the customs of the pagan Saturnalia. The ancient writers are cited at the end of this study to show that such Saturnalia traditions were actually performed, and no direct connection between them can be established.

THE ANCIENT VIEW OF THE JEWS TOWARDS SATURNALIA

To the suggestion of an adoption of Saturnalia traditions for Chanukah, the answer can be returned by looking at the recorded views of the Jewish people toward that very festival of the pagans. This will give fresh perspective to the question of would the Jews assume such pagan practices into their holy memorial of victory against paganism?

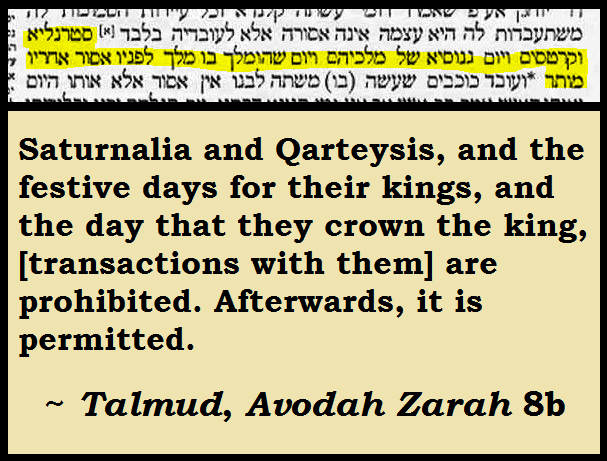

The ancient Jewish text known as the Mishnah, Avodah Zarah 1:3, actually mentions the Roman celebration of Saturnalia.

The ancient Jewish text known as the Mishnah, Avodah Zarah 1:3, actually mentions the Roman celebration of Saturnalia.

The text specifically says that such festivals are for the Gentiles, and as such, are explicitly not observed by the Hebrew people. The other festivals listed were Roman holidays commemorating births of Roman idols and rulers, and victories of Roman expansion. None of these would be expected to be observed by Jewish people worshiping the Creator of all.

The Mishnah as it appears in the Talmud has a slight variation from the above Mishnah manuscript, reading AVODEI KOKAVIM “servants of stars” rather than GOYIM “Gentiles.” The Mishnaic text of GOYIM does not expressly call these people idolaters with the usage of GOYIM. The variant in the Talmud unequivocally makes that point. Additionally, the titles of Kalenda and Saturnalia are somewhat different in pronunciation between the two texts, but the intended meaning is not changed.

That the observance of Saturnalia even in the most fringe and shallow manner – the mere act of seeing such pagan celebration with one’s eyes, was viewed as being enjoined to the scoffers and not delighting in the Torah, but rather, a neglect of the Torah (see Tosefta Avodah Zarah 2:6). In similar manner, the Talmud, in Avodah Zarah 8b, spends some time discussing how much of a distinction needed to be made from any possible or perceived association with these pagan festivals. The topic turns to business transactions, and how even buying or selling from Gentiles immediately-prior to Saturnalia was to be prohibited!

The Mishnah as it appears in the Talmud has a slight variation from the above Mishnah manuscript, reading AVODEI KOKAVIM “servants of stars” rather than GOYIM “Gentiles.” The Mishnaic text of GOYIM does not expressly call these people idolaters with the usage of GOYIM. The variant in the Talmud unequivocally makes that point. Additionally, the titles of Kalenda and Saturnalia are somewhat different in pronunciation between the two texts, but the intended meaning is not changed.

That the observance of Saturnalia even in the most fringe and shallow manner – the mere act of seeing such pagan celebration with one’s eyes, was viewed as being enjoined to the scoffers and not delighting in the Torah, but rather, a neglect of the Torah (see Tosefta Avodah Zarah 2:6). In similar manner, the Talmud, in Avodah Zarah 8b, spends some time discussing how much of a distinction needed to be made from any possible or perceived association with these pagan festivals. The topic turns to business transactions, and how even buying or selling from Gentiles immediately-prior to Saturnalia was to be prohibited!

Understanding the view of the Jewish people toward the pagan festival, it would seem absolutely illogical that they would feel it appropriate in any way to be so bold as to then adopt aspects of such a time of immorality and idolatry, especially for a memorial that expressly celebrated being freed from the influence of such pagan customs.

THE TIMING OF SATURNALIA AND CHANUKAH

The fact that both Saturnalia and Chanukah share an affinity to the winter season has caused some to attempt to make a relation between the two, suggesting that Chanukah is merely a reflection of Saturnalia’s wintry celebration. Upon closer inspection, such a claim is found to be not consistent with the evidence surrounding the dates of the two observances. Understanding this will aid in laying to rest the rumor of a link in the festivals due to approximate position in the season.

The beginning of Saturnalia is on December 17th. That is the oldest date for the pagan festival, but it began to change after the Julian calendar reforms that attempted to correct the drifting of the Roman calendar. Days were added to the celebration. It grew to a span of seven days of observance. Augustus reduced this to just three so that governmental function would not be stopped for so long (Macrobius, Saturnalia, 1.10.4), and it was afterward abolished altogether (Dio, Roman History, LX.25.8), but then re-established officially across the empire for a length of five days (Suetonius, Life of Caligula, XVII; Dio, Roman History, LIX.6.4), until at the end, it was restored informally by the populace for a span of seven days (Martial, Epigrams, XIV, LXXII). In contrast, Chanukah has always been a celebration of eight days – wholly separate from any of the varying lengths of time ever observed for Saturnalia. This should be quite telling in the matter, but more can be said to show the distinction between the two.

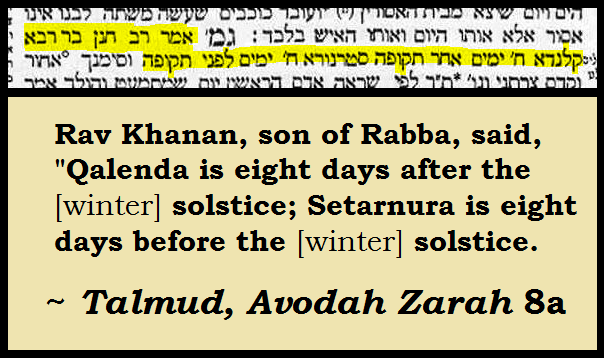

The Jewish people knew when Chanukah happened because they instigated the date for the observance: the 25th day of the month Kislev, and which lasted for an eight-day period. They also were well aware of the Roman observance of Saturnalia that was introduced to them over a century later. The Talmud, in tractate Avodah Zarah 8a, shows they knew well the date for the pagan observance.

The beginning of Saturnalia is on December 17th. That is the oldest date for the pagan festival, but it began to change after the Julian calendar reforms that attempted to correct the drifting of the Roman calendar. Days were added to the celebration. It grew to a span of seven days of observance. Augustus reduced this to just three so that governmental function would not be stopped for so long (Macrobius, Saturnalia, 1.10.4), and it was afterward abolished altogether (Dio, Roman History, LX.25.8), but then re-established officially across the empire for a length of five days (Suetonius, Life of Caligula, XVII; Dio, Roman History, LIX.6.4), until at the end, it was restored informally by the populace for a span of seven days (Martial, Epigrams, XIV, LXXII). In contrast, Chanukah has always been a celebration of eight days – wholly separate from any of the varying lengths of time ever observed for Saturnalia. This should be quite telling in the matter, but more can be said to show the distinction between the two.

The Jewish people knew when Chanukah happened because they instigated the date for the observance: the 25th day of the month Kislev, and which lasted for an eight-day period. They also were well aware of the Roman observance of Saturnalia that was introduced to them over a century later. The Talmud, in tractate Avodah Zarah 8a, shows they knew well the date for the pagan observance.

Because of the somewhat mobile nature of the Hebrew calendar, the festival of Chanukah can occur anywhere from the last week of November into the first week of January. This means that it is not a consistent time of the year on the Roman calendar, which inevitably means it will not likely synch with the timing of Saturnalia in any consistent manner.

If Chanukah was inspired or even largely affected by the Roman Saturnalia, the timing was horribly off. Using computer software to calculate the dates of Chanukah from the time of this writing (2017) and going back essentially one whole millennium, we find the following information comes to light:

Times when the eight days of Chanukah coincided with a seven-day count for Saturnalia, beginning December 17th:

265 different years

Times when the eight days of Chanukah happened entirely prior to December 17th:

668 different years

Times when the eight days of Chanukah happened entirely after a seven-day count for Saturnalia begun on December 17th:

34 different years

The total, therefore, of years during the last millennium where the eight days of Chanukah had no coincidence with the seven-day observance for Saturnalia was 702 years.

This examination did not bother to factor into the mix how much the count would have risen if the original single-day observance was used, or even the three-day or five-day observances. The height of a later seven-day observance for Saturnalia was used alone, as it most closely aligns with time span of Chanukah, even if it doesn’t entirely cover the festival.

If Chanukah was inspired or even largely affected by the Roman Saturnalia, the timing was horribly off. Using computer software to calculate the dates of Chanukah from the time of this writing (2017) and going back essentially one whole millennium, we find the following information comes to light:

Times when the eight days of Chanukah coincided with a seven-day count for Saturnalia, beginning December 17th:

265 different years

Times when the eight days of Chanukah happened entirely prior to December 17th:

668 different years

Times when the eight days of Chanukah happened entirely after a seven-day count for Saturnalia begun on December 17th:

34 different years

The total, therefore, of years during the last millennium where the eight days of Chanukah had no coincidence with the seven-day observance for Saturnalia was 702 years.

This examination did not bother to factor into the mix how much the count would have risen if the original single-day observance was used, or even the three-day or five-day observances. The height of a later seven-day observance for Saturnalia was used alone, as it most closely aligns with time span of Chanukah, even if it doesn’t entirely cover the festival.

FINAL ILLUMINATING THOUGHTS

Rome's presence in Israel did not occur until over a hundred years after the events of Chanukah had come and gone and the traditional observances had already been established. To suggest an influence of Rome's Saturnalia festival upon the rededication observance of the 2nd Temple is to rely upon embarrassingly anachronistic links, which is a fallacious connection at the best, and the calling of a holy true worship event idolatrous, at the worst.

The fact the rabbis of the Talmud knew of Saturnalia - a pagan festival observed by the Gentiles in their very presence, and categorically mentioned it distinctly separate from any hint of Jewish connection should speak volumes to the matter at hand. Their familiarity with it and the lack of any recognized link to Chanukah cannot be dismissed.

The customs of Saturnalia are distinctly their own. Rampant immorality, bizarre social practices, and idolatrous customs abound in that Roman celebration that in no way were ever adopted by the Jews in their observance of Chanukah. The two festivals share no true traditions.

The proposed influence of Saturnalia upon Chanukah is, upon careful assessment, one of absurdity: the thought that a righteous priesthood, willing to spill the blood of their own corrupt countrymen, as well as sacrifice themselves for the sake of the mere hope that pure worship might be restored, would, upon the unlikeliest of military victories, then unabashedly incorporate obvious aspects of an idolatrous festival that would have been observed by their former oppressors is asking us to accept a fiction too unbelievable.

Add to these facets the lack entire of any shared customs between Saturnalia and Chanukah - an oft-declared but vacuous allegation, and the proposal crumbles like the threat of King Antiochus on his deathbed. With no tangible connections extant in the annals of history to tether the profane feast to the faith-based festival, there is no cause for alarm in those who may wish to observe the ancient rededication of the Holy House at the time and in the manner accustomed.

Nothing in Torah precludes us from righteous commemoration of any event in our histories. No edict exists forbidding a memorial mandated by man for a victory of spiritual significance in the lives of the people of Israel. This factor is one that merits elaboration. When the Torah refrains to forbid a thing, when a so-called "thou shalt not" is nowhere to be found, let not man in his zeal overstep his authority by instituting imaginary "thou shalt nots" to satisfy their own assumed convictions. What the Torah of Freedom takes no effort in condemning, may we likewise go not a step further in such matter. To observe a time as of spiritual value due to the salvation of the Holy One for His people is a thing not to be ridiculed or revolted against. Kept in its proper place as a human memorial for His goodness, it remains a fitting time to recall righteous intervention in the histories of our people. Furthermore, through an in-depth examination of the historical details of Chanukah that are linked to surprising Biblical factors, it can actually be proven that this celebration has as its foundation a clear Torah basis and command to be performed by believers (see my study: DEDICATE THE HOUSE). The lighting of a menorah to remember a seemingly impossible triumph stands not at all opposed to the Torah's commandments to observe the ordained festivals from the Most High, but rather, shines a light back upon those divinely-inspired moments as the reason for the willingness to stand up as lights against the tide of darkness in this world.

CITATIONS AND REFERENCES FOR SATURNALIA HISTORICAL FACTS:

Macrobius, The Saturnalia, 1.8.5 Saturn statue with wool removed

Pliny the Younger, Letters 8.7.1; Martial, Epigrams 5.84, 12.81. no school, work, courts

Suetonius, Life of Augustus, 71; Martial, Epigrams 1.14.7, 5.84, 7.91.2, 11.6, 13.1.7; 14.1 gambling with dice, gifts of nuts etc

Seneca, Epistulae 47.14; Martial, Epigrams XIV.1 informal clothing worn

Horace, Satires, book 2, poems 3 and 7. Slaves and masters reversed

Cato the Elder, De agricultura 57; Lucian, Saturnalia 13; drunkenness normal

Macrobius, The Saturnalia, 1.10.18 greeting of Io Saturnalia

Macrobius, The Saturnalia, 1.10.24 gifts of wax sigillaria to appease Hades

Macrobius, The Saturnalia, 1.10.2 the changing of the times of Saturnalia

Tacitus, Annales, 13.15. king of Saturnalia, ordered strange things: singing naked and dunking in ice water

Aulus Gellius, Attic Nights, XVIII.2 friends would gather at the baths to study and discuss the ancient poets

Statius, Silvae, 1.6.57-64 dwarves hunting cranes, women fighting in arena