THE PRODIGALS

by Jeremy Chance Springfield

9/1/2022

Yeshua’s Messianic ministry utilized parables as His prime teaching method. Employing short and relatable stories to encapsulate far deeper spiritual truths, Yeshua was able to present important concepts to the public while embedding in them a more profound value for His disciples. In this way He could simultaneously teach the masses while equipping His inner circle for a world they would soon upend in their proclamation of the Messiah’s arrival.

In Matthew 13:10-13, Yeshua explained to His disciples that He taught in parables to the multitudes so they would not fully grasp what He really wanted His students to learn from His teachings.

12 For to him who has, to him it shall be given, and it shall be abounding to him!

13 And to him that has not, then also that which he has shall be taken from him. Because of this I speak with them in allegories: on account that they see, and do not see, and they hear, and do not hear, and do not understand.”

13 And to him that has not, then also that which he has shall be taken from him. Because of this I speak with them in allegories: on account that they see, and do not see, and they hear, and do not hear, and do not understand.”

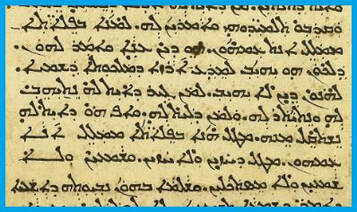

Teaching using parables was not unknown to the Jewish people. Their use is seen in the Hebrew Scriptures most prominently in the book of Proverbs as a teaching method to elucidate concepts first appearing in the Torah. Solomon’s divinely-gifted wisdom enabled him to perceive the Torah's precepts in a simplified manner, allowing him to convey eternal truths in a far more accessible fashion to fellow believers.

As time passed and Israel saw the value in presenting the surface truths of the Torah in a succinct and lucid way, more religious teachers adopted the methodology of Solomon, and parables became a common practice of instruction among the rabbinic schools of Israel. The Talmudic and midrashic literature is full of parables used to convey all kinds of concepts and ideas.

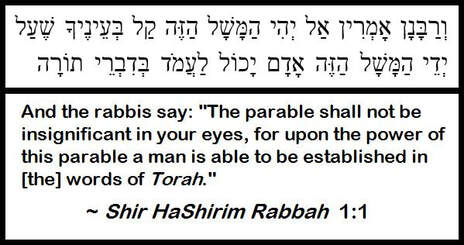

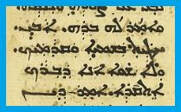

In fact, among the opening words of the ancient midrashic text of Shir HaShirim Rabbah 1:1, extolling the parable for its spiritual value is clearly expressed.

As time passed and Israel saw the value in presenting the surface truths of the Torah in a succinct and lucid way, more religious teachers adopted the methodology of Solomon, and parables became a common practice of instruction among the rabbinic schools of Israel. The Talmudic and midrashic literature is full of parables used to convey all kinds of concepts and ideas.

In fact, among the opening words of the ancient midrashic text of Shir HaShirim Rabbah 1:1, extolling the parable for its spiritual value is clearly expressed.

Yeshua’s choice to utilize parables to present holy concepts would have been a well-recognized course of action.

The Gospels record several instances where Yeshua used parables to also address the educated religious authorities who often opposed the enthusiastic disposition of the public to His Messianic ministry. It is important in reviewing the parables to always note to whom the spiritual allegory was directed, because that can affect how the entire teachings is received.

The Gospels record several instances where Yeshua used parables to also address the educated religious authorities who often opposed the enthusiastic disposition of the public to His Messianic ministry. It is important in reviewing the parables to always note to whom the spiritual allegory was directed, because that can affect how the entire teachings is received.

This study will focus on one parable whose message addressed the negative attitude of the Pharisees towards Yeshua’s willingness to teach even the uncouth and ignorant of the land. Luke 15:11-32, records the parable known popularly as “the prodigal son.” The way in which Yeshua crafted the parable was masterful and absolutely directed to the learned minds and hearts of the Pharisees who were listening and took offense that He chose to reach out to known sinners. What follows will explore the notions presented and show their unique Hebraic significance, which Yeshua intentionally included in His effort to address the stubborn and misplaced view the religious elite held towards their wayward Jewish brothers.

The Torah explains in Deuteronomy 21:17 that the firstborn son is to receive a double portion of the father’s estate, while the second would receive a third of the estate. Depending on the father’s wealth, even receiving only a third could still mean a serious amount of inheritance parsed out to the siblings.

Most importantly, however, the younger son’s request would have been viewed as uncommon and insensitive. Under normal circumstances, a son received inheritance upon the death of his father. By the parable presenting that the younger son asked for it prematurely, it shows his unfortunate state of mind: he cared not for the future, nor for the heart of his father. He sought only the material benefit his father’s eventual death would include.

Most importantly, however, the younger son’s request would have been viewed as uncommon and insensitive. Under normal circumstances, a son received inheritance upon the death of his father. By the parable presenting that the younger son asked for it prematurely, it shows his unfortunate state of mind: he cared not for the future, nor for the heart of his father. He sought only the material benefit his father’s eventual death would include.

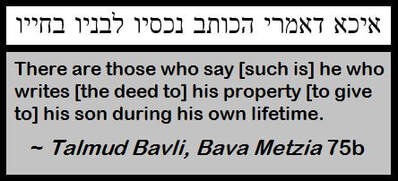

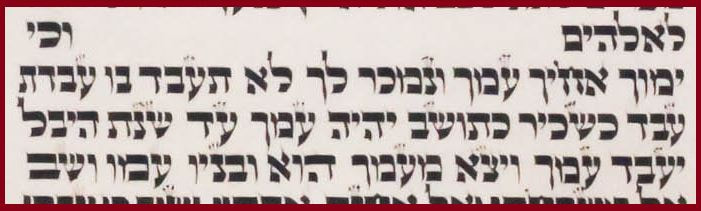

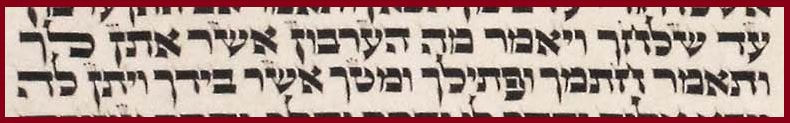

The Talmud Bavli addresses this type of behavior and sets it in the context of one who makes trouble for his father.

Although not usual, the practice apparently did occur enough to be discussed and commented upon by the rabbinic authorities, who saw it as inviting problems that need not even exist. Such a request was also viewed by the community as a whole in a negative light.

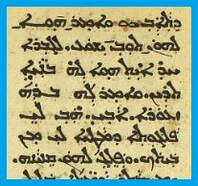

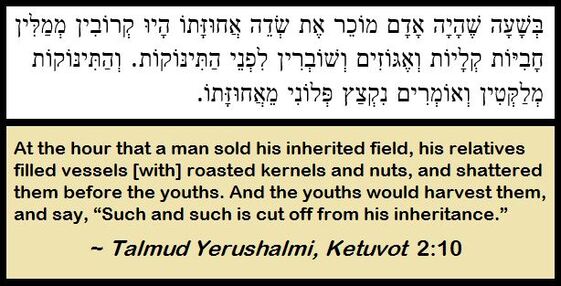

The Talmud Yerushalmi explains a custom performed when a man sold off the property inherited from his family.

The Talmud Yerushalmi explains a custom performed when a man sold off the property inherited from his family.

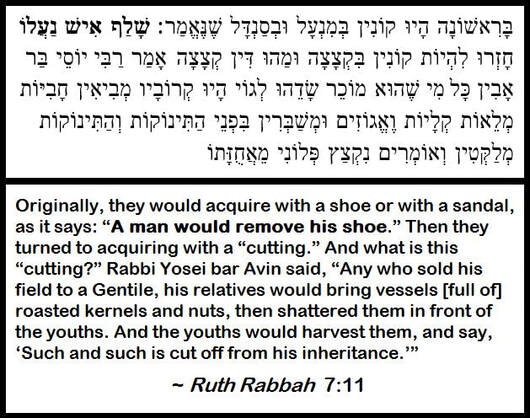

Although this is not the precise situation of the son in the parable, we will read that he engaged in further activity resulting in the squandering of that inheritance while surrounded by non-Jewish people who did nothing to warn him of the consequences of such actions. The midrashic text of Ruth Rabbah addresses further the above custom.

The text speaks of “acquiring” property and how it was done in ancient times, and quotes specifically from Ruth 4:7 as evidence of the method used—both the removing of the shoe, and then later, using a vessel filled with roasted foodstuffs. While the parable makes no mention of this custom, since it was a familiar cultural act under such circumstances, the notion would have certainly been present in the minds of the Pharisees that what the son was asking for and doing was not acceptable, but rather, a shameful request in every way.

The parable picks back up in Luke 15:13.

The parable picks back up in Luke 15:13.

It is worth mentioning that the word “Prodigal” is not exactly a negative term, as it merely refers to something that is “extravagant” or “lavish” in nature. The context in which it is used determines if the word is to be viewed as positive or negative. In the situation of the younger son, his actions with the inheritance he asked to be prematurely given were absolutely prodigal in nature. He lived for a time in a far-off land in sinful extravagance, and when those funds were expended, he found himself in a truly deplorable position.

Luke 15:14-15 details his uncomfortable state.

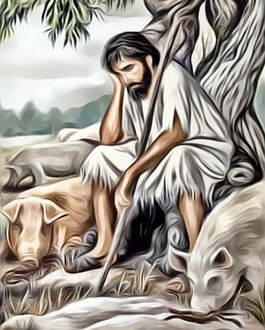

The Torah makes it clear that famine is a judgment from the Creator for when His people are not properly serving Him, as seen in Deuteronomy 28:48 and 32:24. Without funds to maintain his extravagant lifestyle, and due to the famine’s severity, the son was forced into a dreadful servitude—working for someone whom we can only assume was a Gentile, and attending to their swine herd, at that.

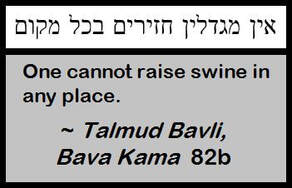

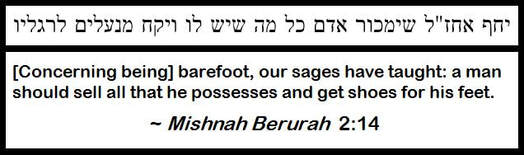

The affront to the son’s faith and heritage was blatant in this detail. The Talmud Bavli mentions how this line of work was forbidden.

The prohibition against believers making a living using pigs helps to show how disobedient and careless the son had become in his poverty. He was willing to flout the expectations of his people in order to survive the famine and his loss of fortune. The lowly position to which the son had descended would have been evident to the Pharisees in his feeding of the swine, but the parable goes on to emphasize just how bad things had gotten with its next detail in Luke 15:16.

The carob tree produces pods that are edible to both man and beast, and in the case of man, are viewed in ancient Judaism as a food for the poor to consume. Today, of course, they are esteemed for various culinary uses without any stigma.

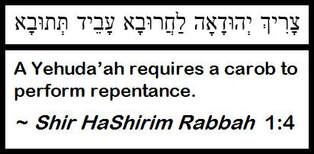

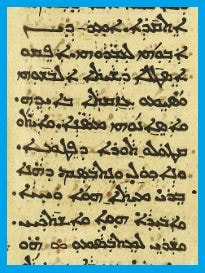

This mention of carobs in the parable also signaled winds of change for the son’s situation, as the food holds another significance within Hebraic thought, which is expressed in the text of Shir HaShirim Rabbah 1:4.

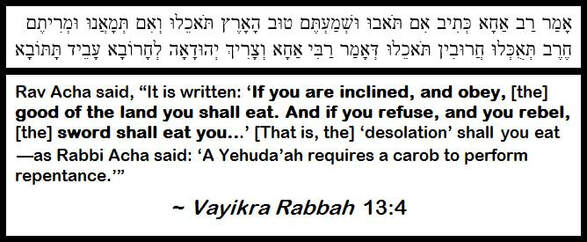

When a Jewish person was forced to eat carobs, it was a sign that they needed to repent, for to do so meant they were in the lowest position in life to which they could fall. The text of Vayikra Rabbah also discusses this factor by connecting to the text of Hebrew Scripture, as well.

Rav Acha and Rabbi Acha are not the same person, just so the reader understands correctly the oddly worded text of the midrash. Rabbi Acha was an Amora of the Amora’im, and Rav Acha was a Savora of the Savora’im who came a generation later and quoted his predecessor’s assertion as validation for his own opinion. Rav Acha quotes from Isaiah 1:19-20 to bring up a point about why a carob is connected to repentance for a Jewish person.

The connection lay through phonetic similarities—a wordplay, in essence. The term “sword” in the Biblical text quoted is CHEREV. The term “desolation” used in Rav Acha’s explanation is CHARUVIN. The term “carob” is CHAROVA.

The connection lay through phonetic similarities—a wordplay, in essence. The term “sword” in the Biblical text quoted is CHEREV. The term “desolation” used in Rav Acha’s explanation is CHARUVIN. The term “carob” is CHAROVA.

Since being obedient is linked to eating the good of the land and being disobedient is linked to being “devoured” by the sword, the vocabulary connections are ultimately made to “devouring” carobs when in need of repentance to once more be obedient.

The parable picks back up in Luke 15:17-19 with the actions of the son upon realizing his situation.

|

17 And when he came to himself, he said, ‘Now how many hired hands are in the house of my father who have for them bread abounding, and here I am perishing in my hunger?

18 I shall rise, go unto my father, and say to him: “My father, I have sinned by Heaven and before you, 19 and I am not further worthy that I be called your son. You must make me as one from your hired hands!”’ |

The conclusions reached by the younger son are worth noting. He had truly been humbled to a point of repentance. Although his mindset had been immature to waste his inheritance, the descent into poverty and reprehensible work situation grew his perspective enough to realize he didn’t deserve restoration, but he could at least have a better life merely as a worker in the estate of his father. This parallels the sinner who is honest in his self-assessment and does not hold himself in improper esteem, knowing that his actions placed him in the position he is in, and any mercy shown would be welcomed.

An interesting detail here is that his sensibilities are restored and his desire to return is mentioned only when the subject of the swine is included. This is not a coincidence. The Aramaic word used for “swine” in the parable is CHEZIRA—“pig.” The Hebrew word for “pig” is CHAZIR, and CHEZIRA is its cognate. However, the root of the term in both languages is the concept of CHAZARAH, meaning “return / repent / restore.” It is very likely that the son spoken of here, being presented with a CHEZIRA daily, saw in it that he could CHAZARAH “return” to his father for a better life. Although not a wordplay in a structural sense in the parable, the conceptual link would likely have been immediately apparent to the Pharisees.

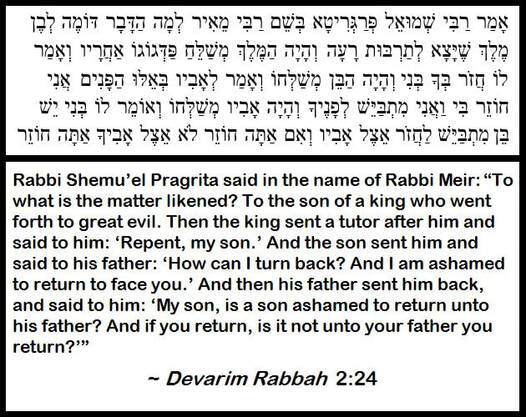

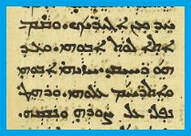

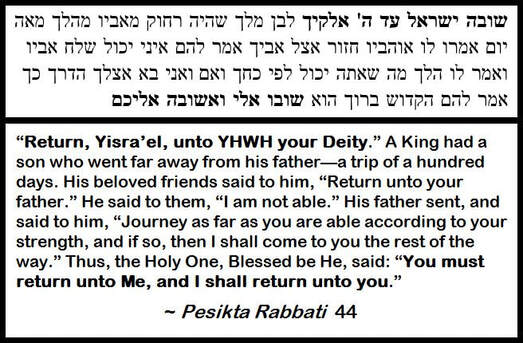

This linguistic link can be seen in the midrashic text of Devarim Rabbah, as it records a similar Jewish parable serving as a worthy supplement to the sentiments of the prodigal at this point in the narrative.

The concept of “return” is emphasized in this midrashic parable, using the familiar Hebrew term CHAZOR / CHOZEYR, being merely a different inflection of CHAZARAH / CHAZIR “return” / “swine.”

Ironically, in attending to the forbidden pigs, the wasteful son found the impetus to draw his heart to return back to the life and family he had so foolishly abandoned. Being forced to wallow in the filth of our choices is often the descent our souls need in order to see that we do not belong so far from the spiritual home that is our true inheritance.

Ironically, in attending to the forbidden pigs, the wasteful son found the impetus to draw his heart to return back to the life and family he had so foolishly abandoned. Being forced to wallow in the filth of our choices is often the descent our souls need in order to see that we do not belong so far from the spiritual home that is our true inheritance.

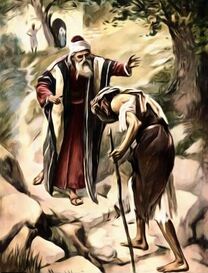

Luke 15:20 continues the parable and emphasizes the father’s prolific compassion that was just waiting to be bestowed upon his wayward son.

The father’s reaction is a powerful testimony to the triumphant love of the Most High. To run into the arms of your child upon seeing his safe return is what any loving parent would do, and if that is so with humans, how much more so with the Creator?

This response is a beautiful expression of the Creator’s willingness to have us back in the safety of His compassion. Another Jewish parable from the text of Pesikta Rabbati presents a very similar account worth mentioning.

Extrapolating on the “return” aspects of Hosea 14:2 and Malachi 3:7, the concept of grace is overwhelming in this parable and exemplifies the grace of the father in Yeshua’s own parable. We may not be able to reach the level of repentance our Father desires of us, but a sinner repenting can do so with the knowledge that the length of his spiritual return is shortened by the eager willingness of the Creator to meet him even before his journey is concluded.

The attitude of the son in the parable highlights his shame over what he had done, as seen in Luke 15:21.

The son expresses his guilt to his father, continuing the sentiment he gave back in 15:19 where he was content to be counted among the hired help rather than foster any expectations of being received again as a son. The shame of servitude in his father’s house was more preferable than living in the dregs of a pagan society.

Leviticus 25:39-40 gives precedent for this potential lifestyle for an Israelite who had fallen into poverty.

He was willing to accept living in a pitiable position, so long as he did not suffer under the hands of people who had no regard for what was right and holy. Not expecting a warm welcome, the son yet received the magnanimous response from the generous heart of his father, as shown in Luke 15:22-24.

|

22 Yet, his father said to his servants, ‘You must bring forth the best robe to clothe him, and you must set the signet ring on his hand, and [with] shoes you must sandal him;

23 and bring, you must kill the ox that is fattened, and let us eat and be merry, 24 that this, my son, was dead, and he is alive; and he was lost, and is found!’ And they began to be merry. |

It is important to note that the father’s demeanor is not only unexpected, but over-the-top; he responds in the positive with as much of a prodigal nature as his youngest son had displayed in his negative acts. In this sense, both father and son could legitimately be referred to as prodigals—both willing to be extravagant with what they had: the son selfishly, the father selflessly.

This unrestrained response of the father can be seen in that he gave the son several important things upon his return.

This unrestrained response of the father can be seen in that he gave the son several important things upon his return.

Consider the spiritual concepts linked to these things elsewhere in Scripture, starting with the robe:

The “best robe” would be a symbol of authority and of being a cherished member of the family. The passage from Isaiah connects it to being “rescued” and being “righteous”—both concepts already linked to this parable of the wasteful son.

The Aramaic text of the Targum Yonatan to Isaiah 61:10 renders the phrase “robe of righteousness” instead as “robe of merit.”

This shows well the status of such a garment when worn—in this case, the impoverished son was not viewed as “cut off” from his inheritance but was included once more as part of the household of his father.

The signet ring is likewise a symbol of identity and authority. The “identity” factor appears in its first usage in Scripture in Genesis 38:18.

The signet ring is likewise a symbol of identity and authority. The “identity” factor appears in its first usage in Scripture in Genesis 38:18.

In this case, the identity of the man Judah was authenticated by the signet ring he wore, and so it was desired as sufficient proof for Tamar. In like manner, the giving of a signet ring to the repentant son displays that his identity is not that of the hired hands in his father’s house but is rather indistinguishable from the rest of the family once more.

The “authority” factor of a signet ring may best be seen from Scripture in the words of Haggai 2:23.

These words were directed to Zerubbabel, who would eventually lead the exiled people of Judah from Babylon back to Israel. His divinely ordained role was symbolized by the signet ring, marking his chosen status to perform the will of the Holy One. The parable’s use of the signet ring being given to the wayward son shows that not only has been accepted once more into the family, but that he has a place and a purpose.

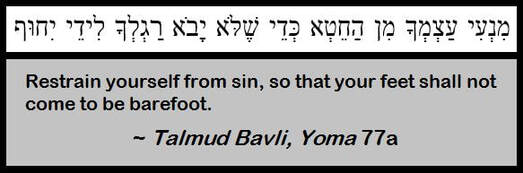

The father’s insistence that the son be shod with shoes upon his return is also significant when we understand the Hebraic concepts involved, as preserved in several Jewish texts of antiquity.

The father’s insistence that the son be shod with shoes upon his return is also significant when we understand the Hebraic concepts involved, as preserved in several Jewish texts of antiquity.

The Jewish sentiment of wearing shoes connects astoundingly well to the parable itself. Additionally, the context of shoes and slaves in the Biblical text is that slaves did not normally wear shoes at all, as seen in Isaiah 20:2-4, and 2nd Chronicles 28:15.

For the son to specifically be given shoes highlights his elevated position in the household. He would not return as a slave or servant, but as a recognized part of the family.

The slaughtering of the fattened ox is also worth mentioning. Normal livestock stayed in the field and fed off the land unless extraordinary circumstances required otherwise. A fattened ox or sheep, however, was segregated from them and usually kept safe in a stable where its diet was controlled and intentionally increased, so that it would gain weight and provide a particularly higher yield of meat, to be slaughtered only upon a special occasion.

The slaughtering of the fattened ox is also worth mentioning. Normal livestock stayed in the field and fed off the land unless extraordinary circumstances required otherwise. A fattened ox or sheep, however, was segregated from them and usually kept safe in a stable where its diet was controlled and intentionally increased, so that it would gain weight and provide a particularly higher yield of meat, to be slaughtered only upon a special occasion.

The command to kill this specific fattened ox shows that the father was serious about rejoicing over the return of this son, and the party that would ensue would have been intense.

The parable ends by turning its attention to the sentiment of the firstborn son to his brother’s return and his father’s exuberant response. Although absent from the parable since the opening line, the oldest son’s reception is a key element to bringing the entire parable to its full meaning. Luke 15:25-28 records what happened.

The parable ends by turning its attention to the sentiment of the firstborn son to his brother’s return and his father’s exuberant response. Although absent from the parable since the opening line, the oldest son’s reception is a key element to bringing the entire parable to its full meaning. Luke 15:25-28 records what happened.

|

25 Yet he, the older son, was in the field, and when he came, and drew near toward the house, he heard the voice of much song,

26 and called to one from the young men and asked him of what this was. 27 He said to him, ‘Your brother came, and your father killed the ox that was fattened, since he received him soundly.’ 28 And he was angry and did not desire to enter. And his father came out, inquiring from him. |

The oldest son received news of his brother’s safe return only after the party had begun. This untimely revelation likely did nothing to ease his disgust over the wanton behavior of his errant sibling.

Unphased that his brother had returned home unmolested save for the loss of his inheritance, the older brother’s offense at the reaction of his father is illuminating. He refused to even enter the house, but remained outside until his father sought him out, too. His feelings about the matter are finally expressed in Luke 15:29-30.

|

29 Yet, he said to his father, ‘See! how many years have I labored for your service, and I did not ever transgress your commands, and not ever was a kid goat given for me that I should be merry with my friends!

30 Yet, for this, your son, while he was prodigal [with] your possessions with prostitutes, and has come, you have slaughtered for him the ox that was fattened!’ |

The faithfulness of the oldest son is brought to the forefront to show that he viewed the situation as unfair and an affront to his commitment to the double portion he would one day receive as his inheritance. He could not understand why their father would act so effusively toward a son who was selfish and inconsiderate towards their family’s plight.

What is truly significant, however, is the parable’s information on what the father did, recorded in Luke 15:31-32. Just as he had not waited until the younger son had reached home to go to him, the father shows his liberal concern yet again for his sons by first going out to his oldest to seek restoration.

What is truly significant, however, is the parable’s information on what the father did, recorded in Luke 15:31-32. Just as he had not waited until the younger son had reached home to go to him, the father shows his liberal concern yet again for his sons by first going out to his oldest to seek restoration.

The father’s words speak to the heart of the situation: the eldest son had everything he could ever want right in front of him. Although the inheritance had not been parsed to him yet, he still had access to it all at any time, for his father was obviously not reserved in enjoying what he had obtained for himself in life. It was vital that the son understood that what really mattered was the fact his younger sibling had returned to the family, because—while possessions serve a function in life—the most important part of life are the people we love and care about.

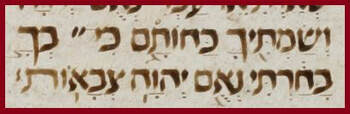

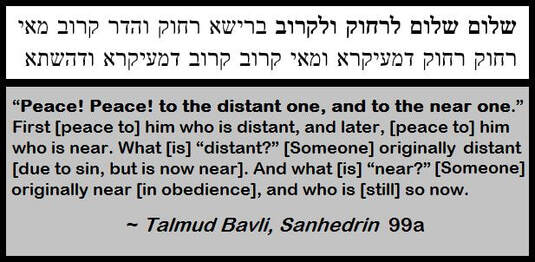

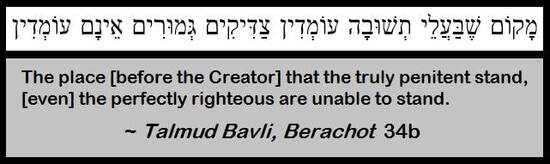

This reality is made clear in a Talmudic passage that connects so well to the parable.

The rabbis quote from Isaiah 57:19, which speaks of peace to the distant and the near. In a unique commentary, it explains the “distant one” as being a repentant soul, and the “near one” as being a steadfastly faithful soul. This aligns perfectly with the parable Yeshua spoke to the Pharisees; the common folk of the day were the “distant” who were returning in repentance (the prodigal son), while the “near” were the Pharisees, who had remained committed to the faith (the firstborn son)—despite missing the truth of that reality, at times.

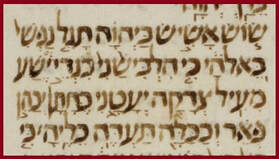

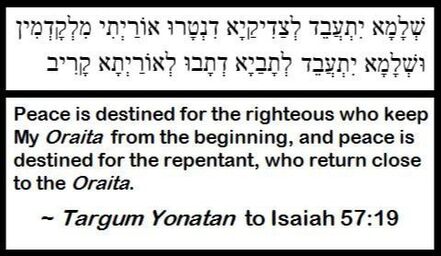

This interpretation of the Biblical passage is made even more clear by looking at the Targum Yonatan to Isaiah 57:19.

This interpretation of the Biblical passage is made even more clear by looking at the Targum Yonatan to Isaiah 57:19.

This Aramaic version distinguishes that spiritual peace belongs to those whose allegiance is to the Word—the Oraita (the Aramaic cognate term for Torah). This is offered liberally to those who have long been faithful as well as to those who have only recently endeavored to return to true worship.

It is this final lesson of the parable that the Pharisees were in dire need of grasping. Their allegiance to the Creator’s commands should have been a foundation causing them to rejoice that the sinners of Israel were hearing the hope of the Kingdom through Yeshua’s compassionate willingness to share with them what was all too often withheld from their ears. If only they could understand the great offer of grace that was set before those sin-shackled hearts, they would see that their Father was always engaged in the work of reconciliation, and so they should be, too.

It is this final lesson of the parable that the Pharisees were in dire need of grasping. Their allegiance to the Creator’s commands should have been a foundation causing them to rejoice that the sinners of Israel were hearing the hope of the Kingdom through Yeshua’s compassionate willingness to share with them what was all too often withheld from their ears. If only they could understand the great offer of grace that was set before those sin-shackled hearts, they would see that their Father was always engaged in the work of reconciliation, and so they should be, too.

Unfortunately, their attitude exposed in them that their own hearts needed a touch of that very prodigal nature—to lavishly exult when the sinner repents. Instead, their refusal meant they were spiritually holding themselves at arm’s length from participating in the redemptive work of the Creator. Matthew 21:31, which is set in the context of further parables Yeshua aimed directly at the Pharisees, exemplifies what was happening.

The text goes on to explain it is because these sinners repented when presented with the truth, whereas the Pharisees had not so joyfully received the Kingdom message. This is a fulfillment of words Yeshua originally spoke at the beginning of His ministry, where He revealed to the crowds of intrigued countrymen that their spiritual walk needed a drastic change in order to be received by the Father’s good graces, as seen in Matthew 5:20.

For a sinner to have any hope of acceptance in the Kingdom, a righteousness surpassing that of the dedicated religious authorities was required. While this might seem impossible, we must remember that the power of repentance can change any wicked heart into a righteous one. The sentiment of the Talmud portrays this spiritual fact in a wonderful manner.

Repentance raises a person higher than any amount of obedience can offer. Yeshua’s willingness to reach out and offer hope to those who were usually neglected by their faith-filled Pharisaic brothers shows that it is the purpose of the righteous to generously elevate those who are in a worse spiritual condition. Their repentance means restoration, but more so, it means they have the opportunity for a spiritual intimacy with their Creator they could not achieve on their own.

The parable of the prodigal displays the need for the faithful to respond to those who are returning with the same profligate acceptance as the One who not only seeks their repentance but runs joyfully to accept them with open arms when they do.

All study contents Copyright Jeremy Chance Springfield, except for graphics and images, which are Copyright their respective creators.