M E S S I A H THE W O R M

by Jeremy Chance Springfield

The Israeli Common Oak, also called the Palestine Oak, or officially Quercus calliprinos, is a variety of the Kermes Oak. It is a low-growing shrub-like tree. On these particular trees are often found an insect that was called in earlier times coccus ilicis in the Latin, and by the modern name of Kermes vermilio. The designation of vermilio is telling us that this little guy is a worm.

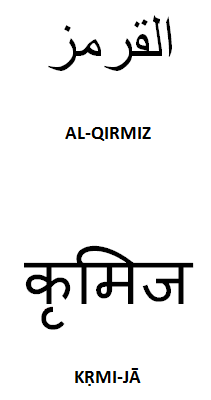

Although small and seemingly insignificant, and not particularly looking much like a worm, this little insect was the key source in ancient times for the precious dye color called “crimson.” In fact, the word “crimson” itself comes from the word Kermes, and can be traced back to the Arabic AL-QIRMIZ, “crimson,” which likely originated from the ancient Sanskrit word KṚMI-JĀ meaning "worm-made."

The dye that is extracted from the bodies of these insects is closely related to carmine, another red dye sometimes used in foods as a coloring agent. In fact, it was only until the relatively recent discovery of the New World source of carmine that crimson from the Kermes vermilio was the primary source for red dye in the world. Today, along with other sources for red, carmine is more predominant, and dye of the coccus ilicis / kermes vermilio is not as widespread as it once was.

An interesting aspect of this creature is what it goes through in order to birth its young. While the insects are born with legs, the females eventually lose the use of their legs, which is apparently why they were given the designation of a "worm." Shortly thereafter, the following amazing events happen:

An interesting aspect of this creature is what it goes through in order to birth its young. While the insects are born with legs, the females eventually lose the use of their legs, which is apparently why they were given the designation of a "worm." Shortly thereafter, the following amazing events happen:

When the female of the scarlet worm species was ready to give birth to her young, she would attach her body to the trunk of a tree, fixing herself so firmly and permanently that she would never leave again. The eggs deposited beneath her body were thus protected until the larvae were hatched and able to enter their own life cycle. As the mother died, the crimson fluid stained her body and the surrounding wood. From the dead bodies of such female scarlet worms, the commercial scarlet dyes of antiquity were extracted.

~ Henry Morris. Biblical Basis for Modern Science, Baker Book House, 1985, p. 73

~ Henry Morris. Biblical Basis for Modern Science, Baker Book House, 1985, p. 73

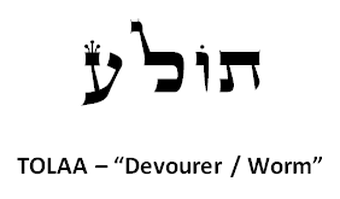

Although the insect does not look much like a worm in the modern usage of the term, it is how the insect has been referenced in writings for a very long time. The above information is significant to us as believers, because surprisingly, this very insect is spoken of in the Scriptures themselves. There, the worm is called in Hebrew TOLAA. The term basically means “devourer,” in respect to the appetite of the insect, which feeds on the sap of a tree. This worm was the key source for the dye crimson/scarlet that one will see mentioned throughout the Bible.

The first time it is used in Scripture is in the book of Genesis 38:28. Therein is the account of Tamar, the daughter-in-law of Judah, and how she forced him to perform the righteous duty of giving her a son when he refused to allow his other son to perform the duty of his deceased brother. In that account, Tamar becomes pregnant with twins from Judah, and when their birth takes place, the firstborn – Zarakh, pushes his arm out of the birth canal, upon which is immediately tied a scarlet thread. The line of Judah was thus secured to continue with the birth of these twins. The verse reads, in a fresh translation from the Hebrew:

And it came to be at her birthing, and a hand was placed forth, and the midwife took it, and tied upon his hand a crimson thread, saying, “This came first.”

The account is of extreme importance, for it actually plays a vital role in understanding how the virgin birth of the Messiah Yeshua is a necessity according to the Torah. This is another teaching in itself, but is mentioned here to see the importance of this event and the inclusion of the crimson thread in a Messianic perspective. The crimson thread and its relation to the Messiah build further in yet another passage.

The first time it is used in Scripture is in the book of Genesis 38:28. Therein is the account of Tamar, the daughter-in-law of Judah, and how she forced him to perform the righteous duty of giving her a son when he refused to allow his other son to perform the duty of his deceased brother. In that account, Tamar becomes pregnant with twins from Judah, and when their birth takes place, the firstborn – Zarakh, pushes his arm out of the birth canal, upon which is immediately tied a scarlet thread. The line of Judah was thus secured to continue with the birth of these twins. The verse reads, in a fresh translation from the Hebrew:

And it came to be at her birthing, and a hand was placed forth, and the midwife took it, and tied upon his hand a crimson thread, saying, “This came first.”

The account is of extreme importance, for it actually plays a vital role in understanding how the virgin birth of the Messiah Yeshua is a necessity according to the Torah. This is another teaching in itself, but is mentioned here to see the importance of this event and the inclusion of the crimson thread in a Messianic perspective. The crimson thread and its relation to the Messiah build further in yet another passage.

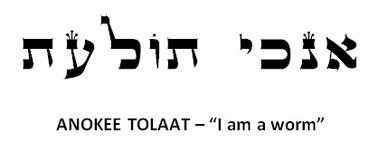

In the book of Psalms 22, we read in the 6th verse that the psalmist makes the declaration “ANOKEE TOLAAT,” – “I am a worm…” The phrase includes the Hebrew name for the insect mentioned above: the kermes vermilio. The verse reads fully:

And I am a worm, and not a man; a scorn of man, and despised of people.

This is extremely significant to the reader, for here we see Messiah making the claim that He is not to be understood merely as what He is in appearance – a man – but rather, what His true purpose entails. The kermes vermilio has to die in order to be of any use to humans. The crimson color cannot be extracted without the death of the worm. In the same way, Messiah’s purpose in His first coming was ultimately to die so that man could benefit from His life-long faithfulness to the Father in all things.

And I am a worm, and not a man; a scorn of man, and despised of people.

This is extremely significant to the reader, for here we see Messiah making the claim that He is not to be understood merely as what He is in appearance – a man – but rather, what His true purpose entails. The kermes vermilio has to die in order to be of any use to humans. The crimson color cannot be extracted without the death of the worm. In the same way, Messiah’s purpose in His first coming was ultimately to die so that man could benefit from His life-long faithfulness to the Father in all things.

Furthermore, the TOLAA / kermes vermilio also must sacrifice itself to bear offspring. It cannot bear offspring without dying, for it forever attaches itself to the tree in order to protect its young while they wait to come forth at their proper time. Additionally, these young feed on their mother for initial sustenance before going forth into the world. These facts directly parallel the Messiah, who had to die in order to see a harvest. It is Him whom we are told to partake of symbolically in the Passover meal, as well.

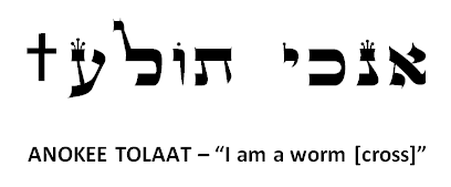

The fact that this sacrificial aspect of the worm happens on wood is itself intensely significant. The death of the Messiah took place on the wood of the cross, and the declaration of ANOKEE TOLAAT here in Psalm 22:6 can be taken as prophetic of when He was affixed to the cross, as the passage goes on to speak of hands being “nailed.”

Additionally, even the way the word TOLAA appears in verse 6 speaks of the sacrifice in a telling manner: there it is spelled TOLAAT. With the addition of the letter Tav, this provides the reader with a powerful imagery to behold. In ancient, pictographic Hebrew, often called Old Negev, the letter Tav actually was depicted exactly like the Christian cross. Therefore, the word as it appears in the passage from Psalm 22:6 could be said to really promote the idea of a sacrificial worm connected to the cross. This factor maintains the link of the Messiah’s purpose of giving everything He had to bring forth a seed for the Father, and doing it by sacrificing Himself for our own future.

Therefore, when one reads that Messiah called Himself a “worm,” it is far more than a statement of self-pity, but a powerful proclamation of His astounding purpose for the redemption of mankind. He took upon Himself the nature of a seemingly insignificant insect that gave of itself for man and for the future of its own offspring. The worm is a portrait of the selflessness of love and the bountiful gift given willingly by the Messiah Yeshua to His sheep.

Therefore, when one reads that Messiah called Himself a “worm,” it is far more than a statement of self-pity, but a powerful proclamation of His astounding purpose for the redemption of mankind. He took upon Himself the nature of a seemingly insignificant insect that gave of itself for man and for the future of its own offspring. The worm is a portrait of the selflessness of love and the bountiful gift given willingly by the Messiah Yeshua to His sheep.

All study contents Copyright Jeremy Chance Springfield, except for graphics and images, which are Copyright their respective creators.