THE SHAMASH

by Jeremy Chance Springfield

12/1/2023

In the darkness of winter, when daylight wanes and the nighttime lingers, believers have the opportunity to shine their light figuratively and literally by observing the festival known as Chanukah. Memorializing the triumph of the faithful priests and the stalwart people of Israel who stood against the encroaching shadow of Hellenization, the eight days provide a spiritual illumination, a testament to our willingness to serve the Creator at the cost of our own safety and well-being, in the hopes that His eternal truths will continue to be safeguarded in this world.

The festival of Chanukah is most recognizable by its unique, eight-branched lampstand, or menorah, often called a chanukiah. Patterned after the eight-day appointed time of Sukkot “Tabernacles,” the festival of Chanukah developed its own special methods to set it apart as distinct from the last of the Biblically ordained holy days. The eight lights of the special Chanukah lampstand can be appreciated as commemorating all who dared withstand the darkness of those idolatrous threats without being overtaken by the shadows.

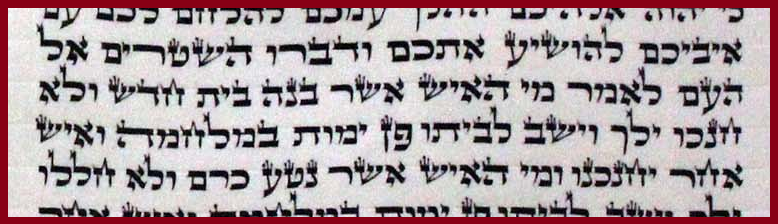

The basis for Chanukah, while itself an extra-Biblical remembrance, is actually found in a commandment from the Torah, located in Deuteronomy 20:5.

The basis for Chanukah, while itself an extra-Biblical remembrance, is actually found in a commandment from the Torah, located in Deuteronomy 20:5.

The words “dedicated” / “dedicate” are CHANAKO / YACHNEKENNU, respectively, and are merely different conjugations of the term we recognize as CHANUKAH “Dedication.” This reveals the Torah’s commandment that a house should be dedicated, and of course that would include the Temple itself, which is what the commemorative festival of Chanukah focuses upon. In this sense, therefore, although not a Biblically mandated festival like those listed in full in Leviticus 23, Chanukah originated as a festival due to obedience to the Torah’s commandment given here.

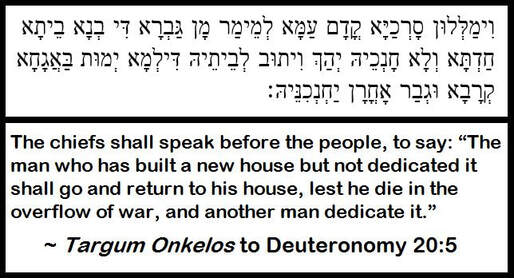

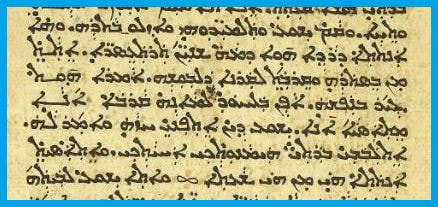

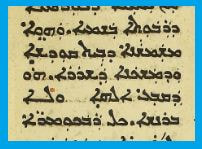

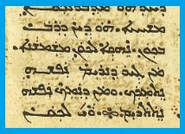

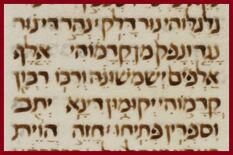

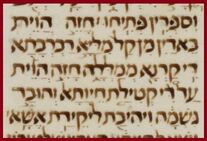

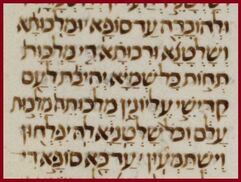

When this same passage is read in its ancient Aramaic Targum of Onkelos, we can see a hint at a further spiritual concept involved in the special time.

When this same passage is read in its ancient Aramaic Targum of Onkelos, we can see a hint at a further spiritual concept involved in the special time.

The term “dedicated,” although in its Aramaic form, is still familiar: CHAN’KEYH. Yet, the intriguing aspect is that it is spelled identically to the term CHANUKIAH – the traditional word for the Chanukah menorah. This could be understood symbolically to mean that we must make our home a Chanukah menorah—that is, we must prepare it to hold the light of true worship.

What does that entail?

How does one dedicate a house?

Additionally, how does one make a house a chanukiah? These are not ever answered in Scripture, but it does give us a foundation from which we can build our own conclusions.

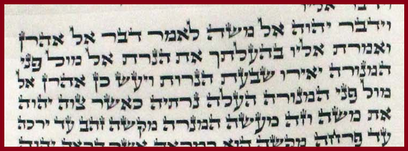

In Numbers 8:1-3, which comes on the heels of the lengthy passage of Numbers 7:10-89, detailing the offerings brought by the tribes to dedicate the Tabernacle in the wilderness, we find that the first act actually performed in the Tabernacle—the true dedication / Chanukah of the original Tabernacle—is immediately recognizable in relation to the festival of Chanukah.

How does one dedicate a house?

Additionally, how does one make a house a chanukiah? These are not ever answered in Scripture, but it does give us a foundation from which we can build our own conclusions.

In Numbers 8:1-3, which comes on the heels of the lengthy passage of Numbers 7:10-89, detailing the offerings brought by the tribes to dedicate the Tabernacle in the wilderness, we find that the first act actually performed in the Tabernacle—the true dedication / Chanukah of the original Tabernacle—is immediately recognizable in relation to the festival of Chanukah.

3 And Aharon did so: over the face of the lampstand he burned the lamps, as YHWH commanded Mosheh.

The inhabitants of the original Holy House—the priests, and in this case Aaron specifically—were tasked with dedicating it by lighting the golden lampstand—the menorah! Thus, the Chanukah of the Tabernacle involved lighting a menorah, and so one could say that symbolically, the Chanukah of a believer’s home entails us lighting the spiritual successor to that menorah—the eight-branched chanukiah!

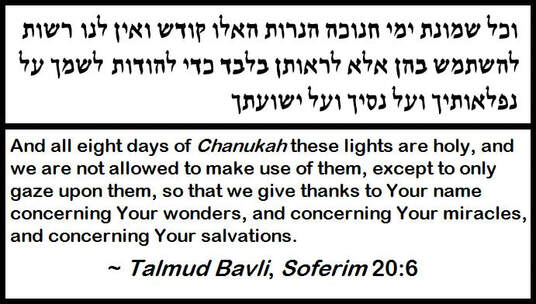

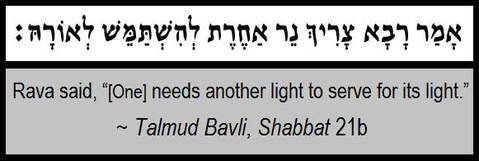

It is of note that the priest himself must bring a flame to kindle the Biblically ordained flames of the lampstand in the Tabernacle and later, the Temple. In similar fashion, the lights upon the chanukiah must also be kindled by a separate source. Based on a declaration from the Talmud Bavli, tractate Soferim 20:6, the eight lights of the Chanukah menorah are special.

Due to their special purpose during Chanukah, one is not permitted to use the eight lights of the chanukiah as a source for mundane illumination in a house. Therefore, a secondary source of light was directed to be used to light them and to remain in order to function as the routine illumination normally gained by household sources of light. This is seen in the Talmud Bavli, tractate Shabbat 21b.

For this reason, many Chanukah menorahs, in addition to the eight branches dedicated for the festival lights, will also provide a ninth location to hold the light used to kindle the others. Included below is an ancient ceramic lamp unearthed in Israel which archaeologists assume to be the earliest example of a chanukiah yet known to history—dated to the first century (presumed to be from 66-70 CE, or possibly up to a century later), as preserved in a collection from The Living Torah Museum.

The ninth holder for the special light that kindles the eight Chanukah lights is not named specifically in the Talmud, other than to be referred to as NER ACHERET “another light.” Over the passing of several centuries, it did receive a specific name, taken from the wording there in the Talmud’s passage, where it says it is “to serve,” using the verb LEHISHTTAMMEYSH. From this conjugated verb, that extra light became known centuries later as the Shamash--a title it has traditionally retained. The term vocalized as such is from the ancient Aramaic language, and is usually translated as “Minister,” “Servant,” or “Attendant.”

The Shamash light, therefore, kindles all eight lights upon the chanukiah. From this root concept of SHAMASH is derived its far more prolific usage found in the Hebrew Scriptures, which is the form of SHEMESH “sun.” In fact, the ancient Akkadian word for “sun” (as well as the name for their version of the sun god) is Shamash, so that they literally referred to the “sun” by the term “Minister.” Akkadian worship of the sun under the designation Shamash endured for centuries, but along with being practiced far to the east of Israel, had also died out long before the events leading to the festival of Chanukah ever happened.

In Ernest Klein’s A Comprehensive Etymological Dictionary of the Hebrew Language, under the entry for SHMSH, it discusses at length the root concept behind the term, and explains some scholars assert that the “sun” definition stems from the concept of “serving” which the root holds also in other ancient Near East languages, like Egyptian and Coptic.

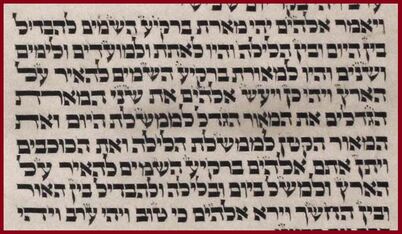

The root concept of SHEMESH “sun” being that of SHAMASH “servant” can be arrived at by returning to the Divine purpose originally given to the sun, as declared in Genesis 1:14-18.

The root concept of SHEMESH “sun” being that of SHAMASH “servant” can be arrived at by returning to the Divine purpose originally given to the sun, as declared in Genesis 1:14-18.

14 And [the] Deity said, “Let be lights in the expanse of the heavens to separate between the day and between the night. And let them be for signs, and for set times, and for days, and for years.

17 And [the] Deity placed them in the expanse of the heavens to illuminate over the earth,

18 and to rule at day and at night, and to separate between the light and between the dark. And [the] Deity saw that it was thus.

18 and to rule at day and at night, and to separate between the light and between the dark. And [the] Deity saw that it was thus.

Note that the Hebrew text says their purpose is to serve the creation: the earth and all that is upon it. These lights function in various ways, attending to the matters of man: they serve as signs in some cases, to call attention to set times (or Scripturally ordained festivals, being the same term in the Hebrew), and to highlight specific days or years. All of this is based on solar and lunar activity, as well as stellar and planetary conjunctions and cometary movements, and even galactic positioning (of the arm of Milky Way galaxy as it traverses the sky, easily visible in low-light pollution environments). In other words, all these are matters of significance to humanity, and thus these objects are in service to mankind and therefore all of creation.

Additionally, the text in Genesis 1 goes on to say that they “rule” the day and the night. This term, while seeming to perhaps be the opposite of “serving,” is merely another aspect of service, as the term used in the Hebrew is the word L’MEMSHELETH, meaning “to rule.” The root of this term, however, sheds light (no pun intended) on the Semitic concept: the word stems from the term MASHAL, which is used in the sense of “proverb” or “parable” in the Hebrew Scriptures. Indeed, the Hebrew name for the book of Proverbs is literally MISHLEI “Parables.” A potentially alternative English title for the book, then, based on the concept at play, would therefore be “Ruling Sayings.” The idea is that a proverb or a parable presents a concise rule of thought to guide or serve the reader into a clarity of understanding in a given topic. Thus, the claim that the sun and moon and stellar objects “rule” over certain matters of man is to say that they serve as guides leading us to understand properly what is happening in the physical creation that reflects Divine intent.

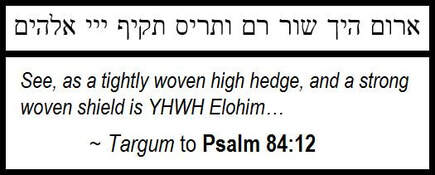

Such a meaning behind the word “sun” is seen in Psalm 84:12 (11 in English versions).

Such a meaning behind the word “sun” is seen in Psalm 84:12 (11 in English versions).

Perhaps not immediately apparent from the English translation, the inclusion of “shield” here signals the reader that “sun” is not likely the most contextually accurate rendering of the term. In that this is poetry text where Hebrew relies most often on parallelism, the rendering of “sun” for SHEMESH does not align with the “shield” that comes after. However, if understood rather as SHAMASH, the poetic parallelism is upheld, as “servant” / “shield.”

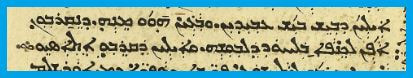

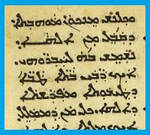

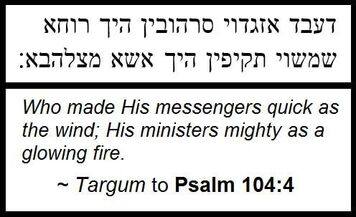

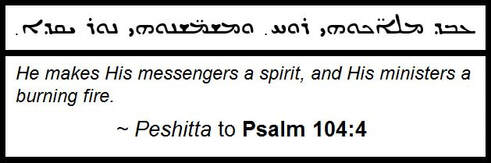

This view is also in the ancient Aramaic translations of the Peshitta and the Targum to Psalms.

This view is also in the ancient Aramaic translations of the Peshitta and the Targum to Psalms.

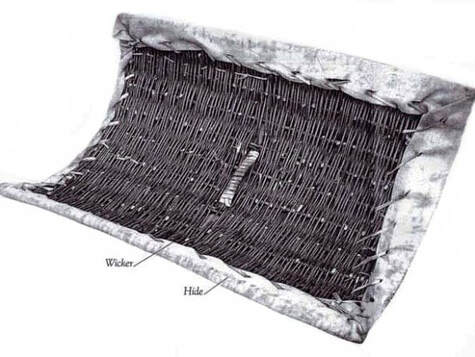

These two ancient translations did not view the Hebrew term of SHEMESH “sun” as the appropriate concept, but rather, understood it from its Aramaic root concept of “serve,” as the Peshitta’s version renders the idea as “helper,” and the Targum—applying a broader sense—as “tightly woven high hedge.” Both renderings are distinctly distant from the concept of “sun,” and point instead strongly to the “serving” / “helping” aspect that is found in the concept of SHAMASH, causing the translator to assume the original scribes were aware of the root meaning and viewed it as the intended idea. Additionally, the rendering of “strong woven shield” speaks not to a circular shield design (which would as such align with a circular sun disc), but rather to a three-sided, woven-from-wood design, usually made from wicker wood—often of the willow tree.

In contrast, the Greek text is of no help, as the Septuagint for this verse omits altogether any potential concepts deriving from “sun” or “shield,” providing no help in attempting to understand the phrase preserved in the Hebrew and Aramaic texts. The Latin Vulgate, likewise, reads essentially the same as the Greek, leaving out the phrase in question.

The conclusion, then, is that the use of SHEMESH in this verse to mean “sun” is likely not its originally intended function, but rather, its root Aramaic form of SHAMASH “servant” / “minister.”

Such a reading can also be seen in another popular passage in the Hebrew Scriptures: Malachi 3:20 (4:2 in English versions).

The conclusion, then, is that the use of SHEMESH in this verse to mean “sun” is likely not its originally intended function, but rather, its root Aramaic form of SHAMASH “servant” / “minister.”

Such a reading can also be seen in another popular passage in the Hebrew Scriptures: Malachi 3:20 (4:2 in English versions).

This passage is actually a more complex issue than the former, as it involves a unique Hebrew poetic device known as a Janus Parallelism. A Janus Parallelism occurs with a thought of a specific context, and then a term is used that could potentially fit that very context, but at the same time, could likewise fit a different context via an alternative definition the term also possesses, and then a second thought is presented that fits that very alternative definition of the term, making the reader realize that both forms of meaning are actually intended by the author, and if only one is understood, the full scope of intention is lost. In this case, the surrounding context of Malachi 3 / 4 mentions the notions of heat and refinement through fire, as well as repeated mentions of serving the Creator. That means the term SHMSH here, usually translated as SHEMESH “sun,” can also explicitly be translated as SHAMASH “servant” / “minister.”

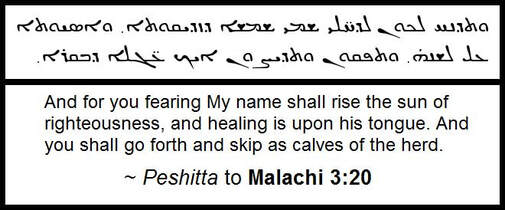

To the latter form, the ancient Peshitta version of the passage provides an alternate reading not found in the Hebrew, which is significant, for unlike the Aramaic Targums, the Aramaic Peshitta typically presents a straightforward, nearly word-for-word translation of the Hebrew original. However, in the Peshitta’s version, a slight variance occurs which alters the way the text would be read to definitely be a SHAMASH “servant / minister” reading.

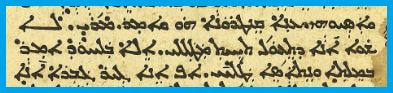

The Peshitta version to Malachi 3:20 (4:2 in English versions) reads as such:

The Peshitta version to Malachi 3:20 (4:2 in English versions) reads as such:

Rather than tell us that the SHIMSHA “sun” has healing in its “wings,” like the Hebrew reads (the sun possessing wings was a motif in many ancient Middle Eastern pagan religions), the Aramaic deviates massively and tells us that the healing comes from “his tongue.” This different concept means the choice of the term SHIMSHA “sun” does not fit as well as the choice of the term SHAMMASHA “servant” / “minister,” who would obviously be a person with a tongue.

This passage is a beautiful Messianic prophecy that we see fulfilled by Yeshua in the New Testament either way it is understood. He is the Shamash who came with healing in His “wings” or “on his tongue,” depending on which passages are addressed:

22 And Yeshua turned and saw her, and said to her, “Have heart, My daughter! Your belief has made you live!” And the woman was healed from that hour!

~ Matthew 9:20-22

~ Matthew 9:20-22

The terms “corner” and “wing” are references to the command in Deuteronomy 22:12 and in Numbers 15:37-40 as the site on a garment of four corners (a Tallit) where a tassel (Tzitzit in Hebrew) is to be placed.

Concerning Messiah healing by word alone, we see Yeshua doing this in the following passages:

Either way the passage from Malachi is approached, incidents are recorded of Yeshua fulfilling it. He is thus the Shamash Himself. Yeshua is even explicitly called the Shamash in Hebrews 8:2, as read from the Aramaic Peshitta text.

Here the Aramaic text uses the similar term M’SHAMSHANA “the minister,” effectively telling us Yeshua is the Shamash of the Temple in heaven!

This term is merely an alternate Aramaic way to say Shamash, being the express noun form of the verbal root. Therefore, M’SHAMSHANA = SHAMASH. The form of SHAMASH is also used in Judaism as a title for a person of particular significance in the synagogue setting. We see a reference to just such an individual in the Aramaic of Luke 4:20.

Here, in a passage where the setting is Yeshua attending a synagogue, the term “minister” is the same word M’SHAMSHANA—otherwise known as the Shamash of the assembly. Historically, the Shamash is an honor held by one or two in a synagogue, possessing certain authority regarding the smooth operations of an assembly and sometimes acting as the attendant to the rabbi. Very often, the Shamash serves in the function of making sure readers are called up to read from the Torah before the whole congregation and follows along to ensure an accurate reading of the Hebrew. In most English versions of the New Testament that are derived from the Greek manuscripts, this same term is rendered as "deacon."

The Shamash is also often referred to by an additional title: GABBAI, meaning a “selector / collector.” The duties of the Gabbai are essentially identical to the Shamash, and the title is often used interchangeably in Judaism. It would seem that this function is hinted at by Yeshua in His words as preserved in the Aramaic of Matthew 20:16.

The passage refers to the “called” and the “selected.” In the Aramaic, the term for "called" is KRAYAH “called” / “invited,” which seems to be a reference to the BAAL KERIAH – “the master of the reading,” being the same term as KRAYAH, just conjugated differently to reflect the necessary nuance of concept ("call" / "read"), which refers to the one who is called up to read from the Torah scroll during the synagogue service.

The term “selected” is G’BAYA and is spelled identically to the Peshitta’s Aramaic form GABAYA—being another way to say GABBAI “collector / selector.” Yeshua is thus hinting that although many are called to the Torah to read from it, not many will function in a servant manner who can themselves read along and make sure the called reader is accurately pronouncing the text.

With this statement using terms meaningful to the religious, we find that He was really saying that He expects us to serve as He served: to be the Shamash the world needs. This is a sentiment Yeshua gave in Matthew 23:11-12, and in several other passages in the Gospels.

Messiah used the Aramaic term M’SHAMSHANA here (which I have rendered as "servant") to speak of our role in this life. We must be humble and know our purpose is to serve others.

This truth is seen well in the Shamash used for the chanukiah. The Shamash is distinctly different than the rest of the lights on the chanukiah. The sole reason it is a part of the festival is to give light to the holy Chanukah luminaries, helping them achieve their purpose of publicizing the miracle of the Creator’s faithfulness. The Shamash is not in itself inherently special like the other lights. It doesn’t even need to be attached to the menorah to do its job. It just needs to provide what the other lights need to glow.

This truth is seen well in the Shamash used for the chanukiah. The Shamash is distinctly different than the rest of the lights on the chanukiah. The sole reason it is a part of the festival is to give light to the holy Chanukah luminaries, helping them achieve their purpose of publicizing the miracle of the Creator’s faithfulness. The Shamash is not in itself inherently special like the other lights. It doesn’t even need to be attached to the menorah to do its job. It just needs to provide what the other lights need to glow.

Such is the purpose of the believer. We have a light in us, and we must use it for the edification and equipping of other believers. We may not be called to be the center of attention, and yet that does not mean we cannot serve the redemptive plan of the Most High. In 1st Peter 4:10 we read from the Aramaic that we must act with honor and integrity and serve others.

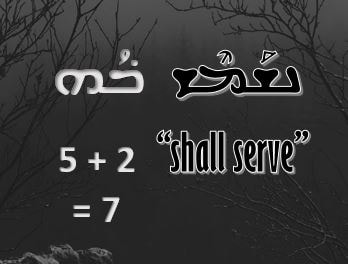

In this passage, Peter wrote that we have received a gift from the Creator. He expects that we N’SHAMESH BAH “shall serve in it” so that others will be blessed. This is our calling before the Holy One.

Interestingly, the term in the text of BAH, meaning “in it,” has the numerical value of 7 (the letter Bet = 2 and the letter Heh = 5, for a sum of 7 in the alphanumeric nature of Hebrew/Aramaic letters), so that one could alternatively read what Peter wrote as instead being “shall serve [the] 7,” which would be a hint to the menorah’s seven lights and the duty of the priest who kindles them.

Psalm 104:4 states it plainly.

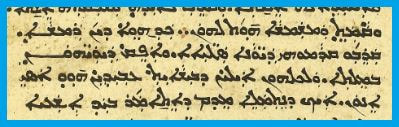

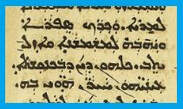

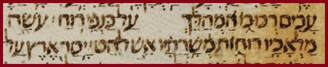

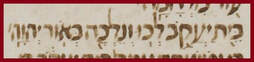

Notice how this is worded in both the Targum to Psalms and in the Peshitta to Psalms:

In both translations the term for “attendants” was rendered using the root concept of SHAMASH “minister.” We are to serve Him faithfully in all that we have ben called to do. It is our high honor to stand and minister before Him in a way that promotes the eternal ideals and the coming Kingdom upon this earth. That was the message of the Chanukah menorah: a spiritual fire, a supernatural purpose fuels us and will not be extinguished, preserving the path forward until the Kingdom of Heaven is realized here in the physical.

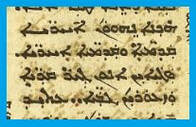

This is seen beautifully in the book of Daniel 7. That chapter is filled with visions of fantastic creatures of symbolic value that have been the subject of much speculation regarding their fulfillment. While there remains to be seen exactly how such prophetic details shall be made a reality, there are other details provided in the text that directly connect to this present study and the importance of believers serving as the Shamash. Look now at Daniel 7:10.

The phrase “ministered unto Him” is the Aramaic YESHAMMSHUNNEYH. It is a long word but is merely a conjugated form of the term SHAMASH. In this passage is thus depicted in the heavens a crowd of Shamashim—“ministers!”

Who are these who are said to have “ministered unto Him” in the vision? The Aramaic text parallels those who ministered with a “river of fire” that flows out from Him. What exactly does this mean? The answer begins to develop in Daniel 7:11.

After mentioning a “river of fire” in the previous verse, we read here that the enemy of the Most High is destroyed and its body is “given to the burning fire.” That is, to the “river of fire” mentioned immediately prior. But what, exactly, is this “river of fire?” The text has actually already told us, but it becomes clearer when we read further on in Daniel 7:27, where we find the explanation of this vision.

The answer is presented: just as the creature was “given to the burning fire” in 7:11, here we see that the “kingdoms of the world” / “body of the creature” are “given to the holy people of the Highest.” The “river of fire” which Daniel saw, therefore, was a symbolic representation of those who act as a Shamash—“minister unto Him”—His people!

From these passages and by returning to the Hebrew and Aramaic texts of Scripture, we are able to see that the development of Chanukah and even the chanukiah and its separate Shamash light were all infused with the spiritual light we are called to shine to this world. Believers must be willing to lay aside personal glory and individual honor, seeking instead to use the Divine gifts we have been so graciously blessed with to serve others. The fire that burns inside each of us has a purpose that is beyond illuminating ourselves, but exists to kindle and minister to the lights that are also being used to publicize the truth: true worship matters, and the kingdoms of this world will one day all be dedicated to the One who dwells in light.

Isaiah 2:5 sums it up for us all who follow the Holy One of Jacob.

Isaiah 2:5 sums it up for us all who follow the Holy One of Jacob.

This is our purpose.

This is the reason we hold the light inside. Our homes must be beacons of His truth, and it is our duty to kindle that reality in this world.

We are servants ministering before the Creator to spread the glow of truth into the darkness. May we show ourselves to be the faithful Shamash who shines His light!

This is the reason we hold the light inside. Our homes must be beacons of His truth, and it is our duty to kindle that reality in this world.

We are servants ministering before the Creator to spread the glow of truth into the darkness. May we show ourselves to be the faithful Shamash who shines His light!

All study contents Copyright Jeremy Chance Springfield, except for graphics and images, which are Copyright their respective creators.