CONNECTING THE DOTS

by Jeremy Chance Springfield

1/28/17

Please, sit down. Get comfortable. I invite you on a journey as we explore a strange and wonderful aspect of the Word that you might not even be aware exists, but hopefully, by the end you will appreciate the depth of the Creator’s heart that He poured into His Word.

I’ll jump right in because I know of no other way to introduce this topic.

This study is about dots.

Dots.

Please, don’t back out yet – I ask for a few more moments of your precious time to explain what I mean. I think you will find it fascinating, and hopefully, in the end, spiritually significant.

So, I repeat myself: This study is about dots.

Not just any dots, though. The dots I am going to discuss are extraordinary. Granted, the preceding sentence is not one you probably ever thought you’d read, nor one that I expected to write, but there it is, so let’s move along.

These particular dots are of significance because they concern an odd placement of printed points preserved in the Torah – the five books of Moses – the Law.

To appreciate these dots, though, you need to return to the actual Hebrew text in which the Law was originally written. English won’t do, unfortunately. If you don’t know Hebrew (yet), don’t fret – I will endeavor to make this as painless as possible and explain it as best I can so everyone can appreciate what will be shared.

Hebrew. A beautiful language, but being it is in the Semitic family of tongues, it is markedly different than English. Among other reasons, it is quite different from English in that it does not require complete vowel markers in order to be read. In fact, the Hebrew alphabet is typically considered to not be possessive of true vowel letters, even though vowels certainly are employed in pronouncing the Hebrew language. Such a detail makes for a unique reading experience.

Think of this example in English:

BRN. If you were to see these letters, what word would you expect them to represent?

I’ll jump right in because I know of no other way to introduce this topic.

This study is about dots.

Dots.

Please, don’t back out yet – I ask for a few more moments of your precious time to explain what I mean. I think you will find it fascinating, and hopefully, in the end, spiritually significant.

So, I repeat myself: This study is about dots.

Not just any dots, though. The dots I am going to discuss are extraordinary. Granted, the preceding sentence is not one you probably ever thought you’d read, nor one that I expected to write, but there it is, so let’s move along.

These particular dots are of significance because they concern an odd placement of printed points preserved in the Torah – the five books of Moses – the Law.

To appreciate these dots, though, you need to return to the actual Hebrew text in which the Law was originally written. English won’t do, unfortunately. If you don’t know Hebrew (yet), don’t fret – I will endeavor to make this as painless as possible and explain it as best I can so everyone can appreciate what will be shared.

Hebrew. A beautiful language, but being it is in the Semitic family of tongues, it is markedly different than English. Among other reasons, it is quite different from English in that it does not require complete vowel markers in order to be read. In fact, the Hebrew alphabet is typically considered to not be possessive of true vowel letters, even though vowels certainly are employed in pronouncing the Hebrew language. Such a detail makes for a unique reading experience.

Think of this example in English:

BRN. If you were to see these letters, what word would you expect them to represent?

BURN BARN BORN BRAN BREN

BRINE BRAUN BRAIN AUBURN

BORNE BERAIN BREEN BORON

BOURN ABORN BRANE BRAINY

Without vowels, you might be left wondering the precise meaning intended by a writer, if the context surrounding did not provide enough clues to narrow the answer to a probable conclusion. In the same way, when Hebrew is read without vowels, there is a possibility for not being clear about what, exactly, is being read.

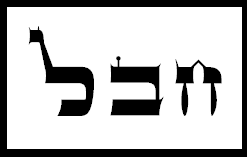

For instance, take this example from all the terms that can be derived from the three-letter Hebrew word spelled Khet-Bet-Lamed:

For instance, take this example from all the terms that can be derived from the three-letter Hebrew word spelled Khet-Bet-Lamed:

WIND UP DAMAGE OVERTHROW

SORROW PLEDGE PERVERSION

SAILOR ROPE MAST

For this reason, you will find that in many written Hebrew publications, a system of vowel “marks” or “points” are added to the Hebrew text to aid the reader in properly identifying the words contained therein. They are constructed of dots and dashes that are placed above or below the Hebrew letters, and allow the reader to pronounce the terms written with precision, yielding an accurate reading comprehension. These vowel markings are well over a thousand years old, and have faithfully preserved the general pronunciation of the ancient Hebrew text for us to this very day. The Hebrew name for these marks is NIQQUDOT, or as you might sometimes see in transliteration, NIKKUDOTH / NIKUDOS.

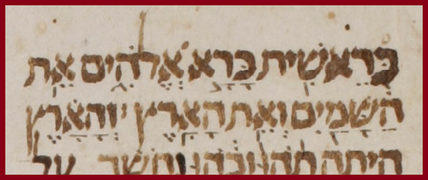

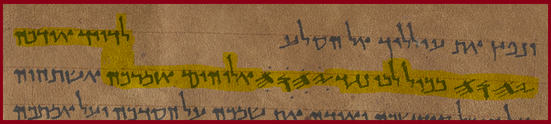

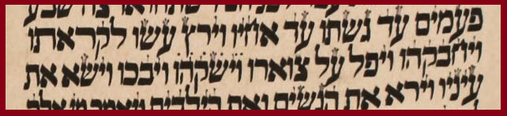

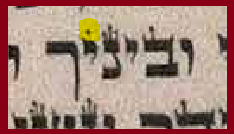

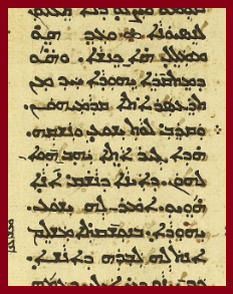

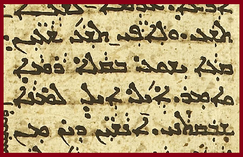

Provided is an example of an ancient Hebrew manuscript of Genesis 1:1 that contains such niqqudot for proper pronunciation.

Provided is an example of an ancient Hebrew manuscript of Genesis 1:1 that contains such niqqudot for proper pronunciation.

The dots and dashes you see above and below the letters have specific vowels assigned to them, so that the reader can properly pronounce and identify every word in a text. Any Hebrew language grammar book will provide the charts that show what vowel sounds are attached to which niqqudot.

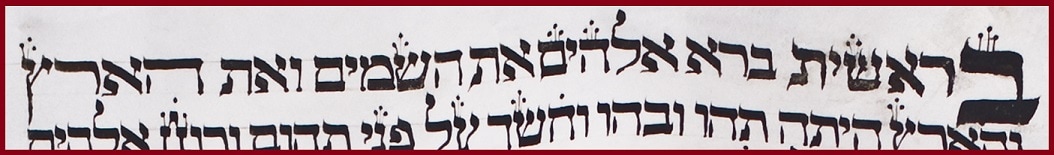

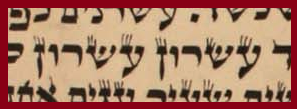

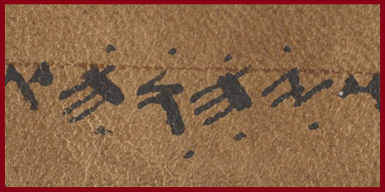

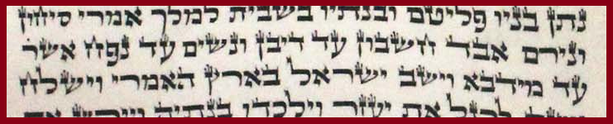

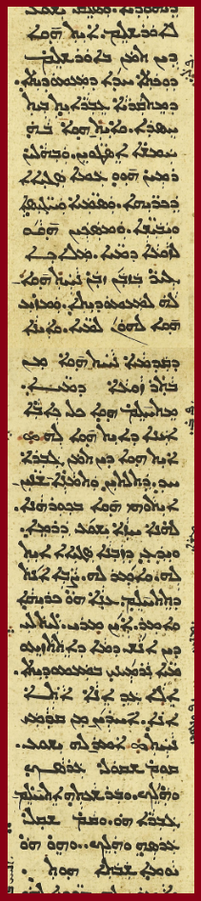

What is interesting, though, is that while texts with vowel-points are allowed to be used in Hebrew books, when it comes to an actual scroll of the Hebrew Bible, such method is forbidden. There are no pronunciation helps in the form of the familiar vocalization dots and dashes to be found in a proper scroll of Scripture. That’s right – you have to know how to pronounce the text or else you might easily make a mistake. Here is an example from a Lithuanian Torah scroll showing Genesis 1:1 to let the reader see the clear absence of niqqudot in the scroll. The lines that extend from the top of the letters you see here are not dots, but tagin, a different aspect of Hebrew letters altogether.

What is interesting, though, is that while texts with vowel-points are allowed to be used in Hebrew books, when it comes to an actual scroll of the Hebrew Bible, such method is forbidden. There are no pronunciation helps in the form of the familiar vocalization dots and dashes to be found in a proper scroll of Scripture. That’s right – you have to know how to pronounce the text or else you might easily make a mistake. Here is an example from a Lithuanian Torah scroll showing Genesis 1:1 to let the reader see the clear absence of niqqudot in the scroll. The lines that extend from the top of the letters you see here are not dots, but tagin, a different aspect of Hebrew letters altogether.

No niqqudot are to be found to help someone in pronunciation who is reading from a Hebrew scroll. However, this is where it becomes somewhat complicated. While there certainly is an entire lack of vowel-points in a scroll of Scripture, it does not mean that there are absolutely no niqqudot to be found in one!

Does it sound like I’ve just contradicted myself?

Don’t vowel-points = niqqudot?

What is going on?

Actually, vowel markings are called niqqudot, it is true, but in reality, the term is used more anciently to point (pun entirely intended) to something else altogether – dots in the scroll of Torah that have nothing to do with pronunciation!

Are you confused, yet? Don’t be. We are just getting started, and it is about to get very, very interesting!

Concerning a Hebrew scroll of the Torah, although no vowel marks are allowed to be written in the text, the scribe who writes it is actually commanded to include dots in a few very specific places throughout several of the books of the Law. The dots are placed above a letter always, and are inked-in enough to clearly distinguish them as an intentional work of the scribe. These dots are called in the ancient Hebrew texts that discuss them niqqudot. Therefore, although the term niqqudot is typically used in modern times to reference the system of vowel-points added to the text of Hebrew writings to aid in pronunciation, the ancient use of the term was actually in reference to a different set of dots in use in a scroll of Torah that had a unique significance altogether. Western Bible scholars, in their typical fashion, opt for the fancy designation of puncta extraordinaria when referencing them. Whether you call them that, or the traditional niqqudot, or simply “dots,” their compelling presence in the text cannot be ignored once they are discovered.

Does it sound like I’ve just contradicted myself?

Don’t vowel-points = niqqudot?

What is going on?

Actually, vowel markings are called niqqudot, it is true, but in reality, the term is used more anciently to point (pun entirely intended) to something else altogether – dots in the scroll of Torah that have nothing to do with pronunciation!

Are you confused, yet? Don’t be. We are just getting started, and it is about to get very, very interesting!

Concerning a Hebrew scroll of the Torah, although no vowel marks are allowed to be written in the text, the scribe who writes it is actually commanded to include dots in a few very specific places throughout several of the books of the Law. The dots are placed above a letter always, and are inked-in enough to clearly distinguish them as an intentional work of the scribe. These dots are called in the ancient Hebrew texts that discuss them niqqudot. Therefore, although the term niqqudot is typically used in modern times to reference the system of vowel-points added to the text of Hebrew writings to aid in pronunciation, the ancient use of the term was actually in reference to a different set of dots in use in a scroll of Torah that had a unique significance altogether. Western Bible scholars, in their typical fashion, opt for the fancy designation of puncta extraordinaria when referencing them. Whether you call them that, or the traditional niqqudot, or simply “dots,” their compelling presence in the text cannot be ignored once they are discovered.

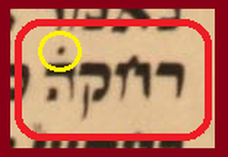

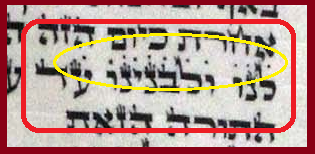

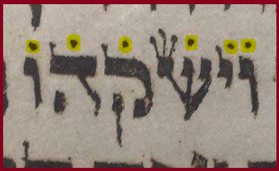

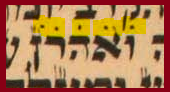

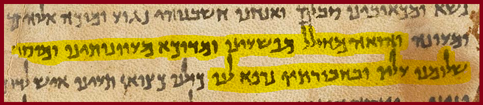

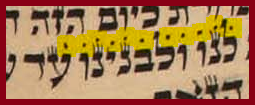

An example is given here from Genesis 33:4, showing an image from a vocalized manuscript on the left, with the niqqudot that represent vowels as well as the ancient niqqudot that do not represent vowels – which I have digitally highlighted. On the right is an image from an actual Torah scroll with the ancient niqqudot again highlighted for comparison. The reader can see that even though all vocalization is left out of a scroll of Torah, the ancient form of the dots that are not intended for pronunciation remains in the text.

These are the true niqqudot of the Torah.

They have existed in the scrolls for thousands of years, and the purpose for them is one that has elicited lots of discussion by rabbis and commentators over the centuries. Their significance is admitted by all, but the specific reason for their existence is debated. The Jewish sages had all kinds of things to say about them in their various appearances in the Torah. In fact, this study is aimed at adding my own thoughts to the mix, which we will get to soon enough for your consideration. But first, some history from Judaism on the matter might help to show that the rabbinic teachers were openly somewhat mystified by the presence of these conspicuous dots in the Torah.

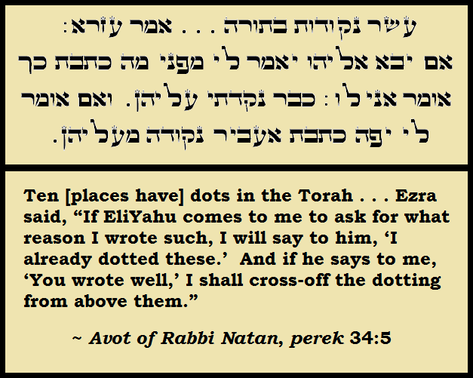

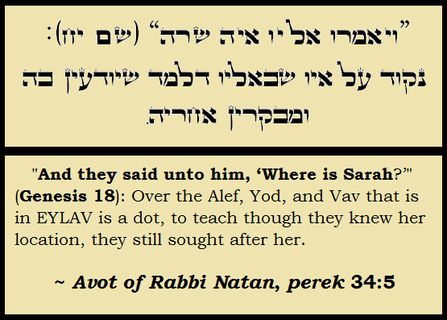

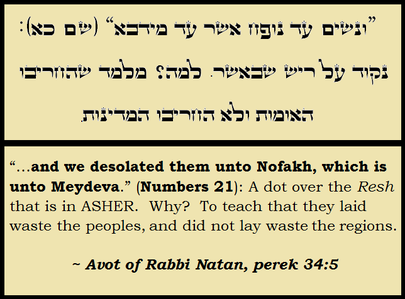

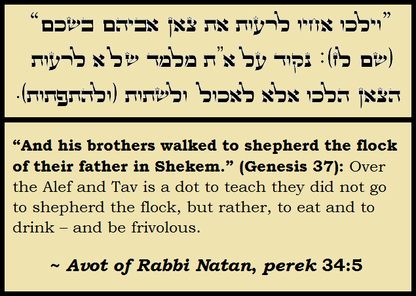

In the ancient text of the Avot of Rabbi Natan, which is considered a minor tractate of the Talmud Bavli, we read the affirmation of the existence of these unusual niqqudot in the Torah, and the most widely-held theory in Judaism for their purpose.

They have existed in the scrolls for thousands of years, and the purpose for them is one that has elicited lots of discussion by rabbis and commentators over the centuries. Their significance is admitted by all, but the specific reason for their existence is debated. The Jewish sages had all kinds of things to say about them in their various appearances in the Torah. In fact, this study is aimed at adding my own thoughts to the mix, which we will get to soon enough for your consideration. But first, some history from Judaism on the matter might help to show that the rabbinic teachers were openly somewhat mystified by the presence of these conspicuous dots in the Torah.

In the ancient text of the Avot of Rabbi Natan, which is considered a minor tractate of the Talmud Bavli, we read the affirmation of the existence of these unusual niqqudot in the Torah, and the most widely-held theory in Judaism for their purpose.

This is the most popular response given in Judaism as to the purpose of the dots that appear in a Torah scroll. The idea espoused here is that Ezra the scribe, who is largely believed to be the one responsible for collating the various texts of the Hebrew Scriptures and setting them in order as divinely-inspired revelations, for some reason viewed the letters and words that are dotted as questionable, and so placed dots over them to call attention to their presence, with the hope that on the day Elijah comes, he will be able to verify their legitimacy or not.

This approach has its issues, however. The idea that dots could be used to highlight words that erroneously appear in a religious text – without outright erasure of the suspected terms, is one that is not foreign to Judaism, to be clear. In fact, there is precedent for it in the Hebrew text of Scripture itself. Outside of the Torah, there appears in the book of Psalms an incident of dots around a word of questionable placement in the text. In the Dead Sea scroll text of Psalm 138:1, there is a variant reading not found in all other extant texts of the book.

First, the generally-accepted reading is as follows:

This approach has its issues, however. The idea that dots could be used to highlight words that erroneously appear in a religious text – without outright erasure of the suspected terms, is one that is not foreign to Judaism, to be clear. In fact, there is precedent for it in the Hebrew text of Scripture itself. Outside of the Torah, there appears in the book of Psalms an incident of dots around a word of questionable placement in the text. In the Dead Sea scroll text of Psalm 138:1, there is a variant reading not found in all other extant texts of the book.

First, the generally-accepted reading is as follows:

For David. I shall praise You with all my heart. Before deities I shall sing to You!

This is the version that is universally-accepted as inspired. Notice now the version from the Dead Sea scrolls, which has a new addition in it:

For David. I shall praise You, YHWH, with all my heart. Before YHWH the Deity I shall sing to you.

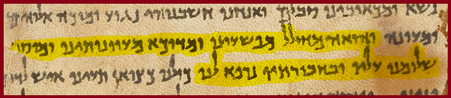

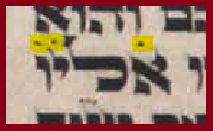

The variant is the addition of the Divine Name twice into the text. The first time is no real problem, in that the Identity is obvious in that respect. It is the second addition of the Divine Name that creates the real problem, and even the Dead Sea scroll scribe realized that fact at some point after it was written by adding the niqqudot above and below the Name.

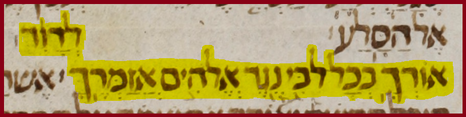

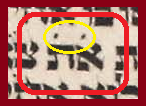

Look carefully at this closer image to see the dots around the Name.

Look carefully at this closer image to see the dots around the Name.

The dots appear here above and below the Name, which is unique in how they are used in the Hebrew Bible. In the ten different places in the Torah, as shall be discussed further, the niqqudot that are preserved are always above the letters – never above and below. This sole instance in Psalms shows the use of the niqqudot to draw attention to the improper addition of the Name here. The majority of texts, which do not have the Name in this verse, rightly have David declaring that He would sing to the Most High “before” or “in the presence of” other deities – that is, he would proclaim the Creator in worship even if in a situation where he was confronted with idol worshippers. He is saying that he would be bold and not back down in praising the Holy One. In contrast, the variant appearance of the second Name found in the Dead Sea scroll version has David singing to an unidentified “you” while in the Presence of the Most High – a frightening declaration that actually conveys the opposite of what the text should be saying!

I have endeavored to point out this detail to show that the use of dots above and below a word is how a scribe really intends that a term is out-of-place in the text if he wishes, or is unable, to erase it. When niqqudot appear over a term – as they do in the scrolls of Torah, something else is instead meant. Furthermore, as shall be seen, the ways many of the dots are used in the Torah are not conducive for the idea of them being error-markers, as the example from the Dead Sea scroll of Psalms clearly indicated. The reason is that, in seven of the ten different locations in which the niqqudot appear over words in the Torah scroll, not every letter is even dotted! In fact, some instances have only certain letters of a word with a dot above them, while skipping others – a method that doesn’t make any sense at all if the original usage of the niqqudot were to merely mark a word that should not be in the text.

The only logical conclusion when these matters are realized is that the dots stand for something else, as well as their placement in the text being significant. What all that could be is the true focus of this study. The majority of discussion on the niqqudot of the Torah by the ancient commentators in Judaism is centered on attempting to answer the meaning of the inclusion of these dots in their particular locations in the text.

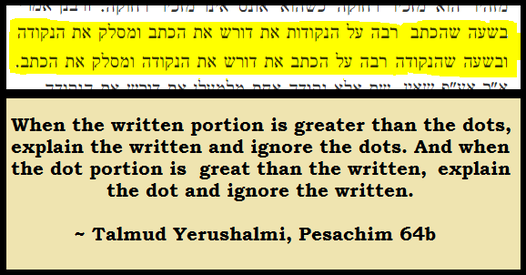

The Talmud Yerushalmi, in Pesachim 64b, discusses how one might approach the presence of the niqqudot in the text in such a way as to make sense of them.

I have endeavored to point out this detail to show that the use of dots above and below a word is how a scribe really intends that a term is out-of-place in the text if he wishes, or is unable, to erase it. When niqqudot appear over a term – as they do in the scrolls of Torah, something else is instead meant. Furthermore, as shall be seen, the ways many of the dots are used in the Torah are not conducive for the idea of them being error-markers, as the example from the Dead Sea scroll of Psalms clearly indicated. The reason is that, in seven of the ten different locations in which the niqqudot appear over words in the Torah scroll, not every letter is even dotted! In fact, some instances have only certain letters of a word with a dot above them, while skipping others – a method that doesn’t make any sense at all if the original usage of the niqqudot were to merely mark a word that should not be in the text.

The only logical conclusion when these matters are realized is that the dots stand for something else, as well as their placement in the text being significant. What all that could be is the true focus of this study. The majority of discussion on the niqqudot of the Torah by the ancient commentators in Judaism is centered on attempting to answer the meaning of the inclusion of these dots in their particular locations in the text.

The Talmud Yerushalmi, in Pesachim 64b, discusses how one might approach the presence of the niqqudot in the text in such a way as to make sense of them.

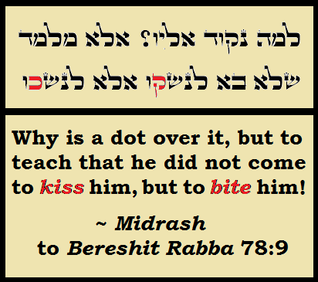

This view is also repeated in the Midrash, in Bereshit Rabba 78:9. Using this method, different rabbis and commentators of antiquity attempted to elicit meaning from the niqqudot in their various appearances in the Torah. This approach resulted in ideas that are sometimes interesting, and sometimes just odd, or seem quite forced. As one reads the rabbinic commentary on these dots throughout the ages, it becomes clear that their purpose is truly not at all clear to the Jewish religious mind.

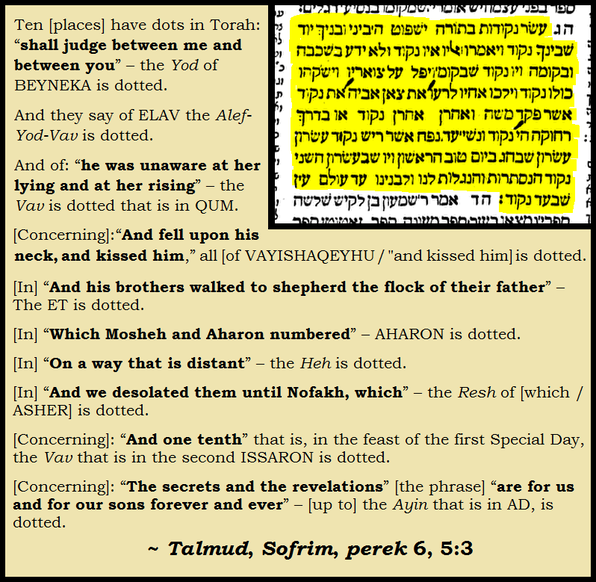

In the Talmud, there is a minor tractate called Sofrim that is devoted entirely to explaining the traditional laws concerning the writing of scrolls of Scripture. In it, we have a complete list of the ten passages that contain the niqqudot found preserved in the Torah. That excerpt is presented here before dealing with them individually.

In the Talmud, there is a minor tractate called Sofrim that is devoted entirely to explaining the traditional laws concerning the writing of scrolls of Scripture. In it, we have a complete list of the ten passages that contain the niqqudot found preserved in the Torah. That excerpt is presented here before dealing with them individually.

Let us take a look, now, at the ten different passages in the Torah which possess these curious niqqudot, noting the different ideas offered to explain them over the years, and afterwards attempt also to make sense of them, perhaps, in a new way that seeks to unify their presence and purpose in the text of Holy Scripture.

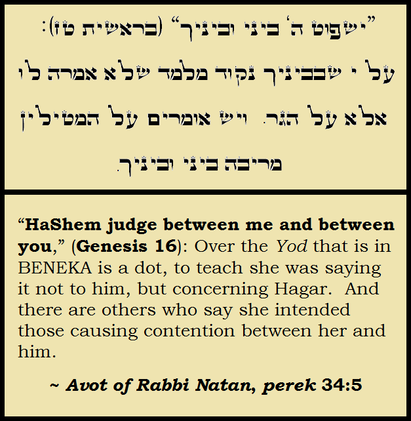

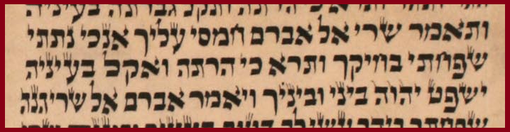

The very first occurrence of a dot in Scripture is preserved for us in the book of Genesis 16:5. The context for the story is that Abraham and Sarah have been unable to conceive during their marriage, and yet spurred by the promise of the Most High that they would have a son, Sarah extends her maidservant, Hagar, to Abraham in hopes that through her the prophecy of their progeny would be fulfilled. Abraham agrees, Hagar soon conceives, and then the problems begin. With Hagar being able to provide a fertile womb for the husband of her mistress, she starts to experience a change of attitude toward the barren woman. Hagar’s personality erupts in airs of supremacy and oppression towards Sarah, and Sarah goes to her husband about the dangerous turn of events.

And Sarai said to Avram, “My [being] wronged is upon you! I gave my handmaid into your bosom, and when she saw she conceived, I was diminished in her eyes! YHWH shall judge between me and between you.”

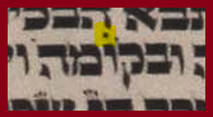

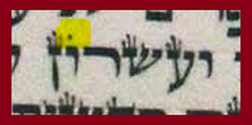

The last term in the verse from the Hebrew contains the dot - UVEYNEKA - "and between you." I have zoomed-in and indicated the term and the dot in all of these instances to help the reader see exactly where and how the niqqudot are used in each situation.

The traditional take on the meaning of this one dot according to Judaism can be found in the Avot of Rabbi Natan, perek 34:5, which devoted time to listing the entire set of dots and offers an explanation for each.

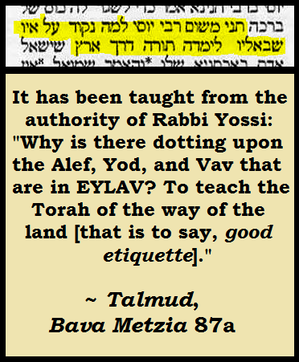

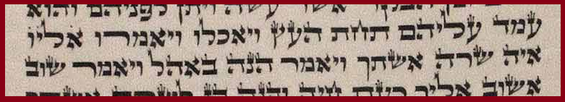

The second passage containing niqqudot in the Torah is Genesis 18:9. The context in this passage is the visitation of the three “men” / angels to Abraham and Sarah to announce that the aforementioned promised son would come directly from the womb of Sarah. Upon meeting Abraham, they have this conversation:

And they said unto him, “Where is Sarah your wife?” And he said, “See! in the tent.”

This second passage marks the first instance of multiple dots over a word in the Torah. In this case, it is over the term EYLAV - "unto him."

The Talmud Bavli, in tractate Bava Metzia 87a, discusses these dots and what they believe is being conveyed by them.

Alternatively, the Avot of Rabbi Natan takes a markedly different view of the matter, telling us the following:

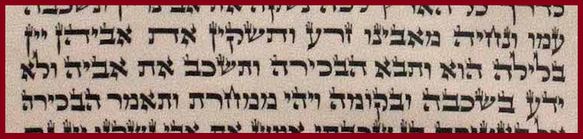

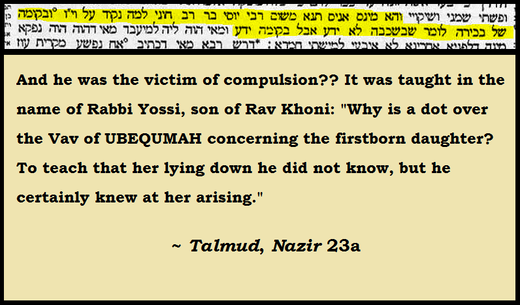

The third passage with a dot in the Torah is in Genesis 19:33. The context here is the story of Lot and his daughters, who inebriate him after the conflagration of Sodom and the cities of the plain. Their plan, thinking the population centers of the earth have all been razed from heaven’s wrath, is to conceive from their father in the hopes to continue the race of men through the Scriptural act of YIBUM [For more on that strange concept, see my study: THE VIRGIN BIRTH IN TORAH]. The dot is found in the first instance of those scandalous events.

And they made their father to drink wine in that night. And the firstborn went in, and lay with her father, and he was unaware at her lying, and at her rising.

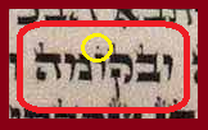

Only a single letter is dotted in this third instance - the letter Vav in the word UVEQUMAH - "and at her rising."

The Talmud Bavli, in tractate Nazir 23a, discusses what they believed the dot intended in the term. The exact same perspective is shared on this dot elsewhere in the Talmud, in tractate Horayoth 10b, essentially verbatim, so I will feign to quote it in its entirety here.

A differing opinion is given in the Avot of Rabbi Natan, perek 34:5, where he says that the dot conveys the opposite information.

A differing opinion is given in the Avot of Rabbi Natan, perek 34:5, where he says that the dot conveys the opposite information.

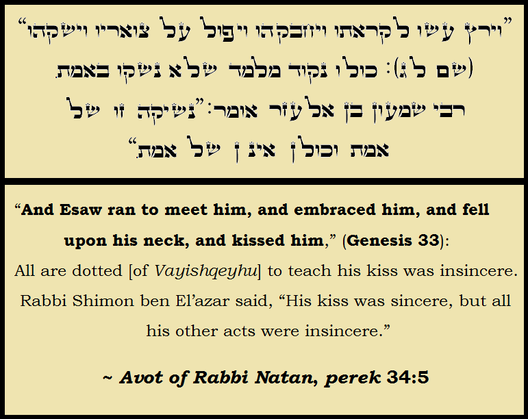

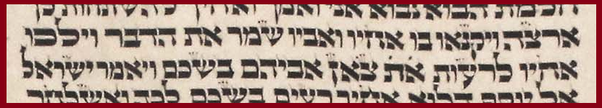

The fourth passage containing niqqudot in the Torah is in Genesis 33:4. In this instance, the context concerns the return to Israel of Jacob from land of Aram, and his meeting with his long-estranged brother, Esau. When they last saw each other twenty years before, Jacob had betrayed Esau by stealing his firstborn blessing, and so he feared such anger had only been kindled over the years, making him dread the reaction of his older brother upon seeing him again. The event played out somewhat differently than Jacob expected:

And Esaw ran to meet him, and embraced him, and fell upon his neck, and kissed him, and they cried.

This is interesting in that it marks the first time in the Torah where a word is given dots over every single letter of the term VAYISHAQEYHU – “and kissed him.”

The Jewish commentators have differing opinions on this set of dots. The noted teacher, Ibn Ezra, suggested mindfully ignoring them altogether, but Rabbi Yannai, as recorded in the Midrash of Bereshit Rabba 78:9, said Esau was really attempting to bite Jacob, based on the almost identical spelling of the words “kiss” and “bite” in Hebrew. The suggested concept would read VAYISHAKEYHU “and bit him” – a phrase differing in only one letter – the Kaf instead of the Qof of the actual text – letters which I have signified by placing in red in the quote provided from the Midrash.

The discussion on the issue shows us that they viewed it in varying light. The Avot of Rabbi Natan, perek 34:5, sums up the matter of dispute quite well.

The fifth occurrence of dots over a word in Torah is found in Genesis 37:12. The account records the incident where Joseph’s brothers sell him into slavery. It first discusses the sharing of prophetic dreams Joseph had with his family, and then the story begins.

And his brothers walked to shepherd the flock of their father in Shekem.

This is the second word in Torah that is entirely dotted. The term ET is unique in that it really is not translatable into English. It is supposed to help aid the reader as a grammatical nuance, and so the term in itself is very weird to see it as the word that was viewed in need of being dotted.

The odd choice to place niqqudot over this word did not, however, prevent the sages from attempting to make sense of it. Once again, we can turn to the Avot of Rabbi Natan to see how these dots were viewed.

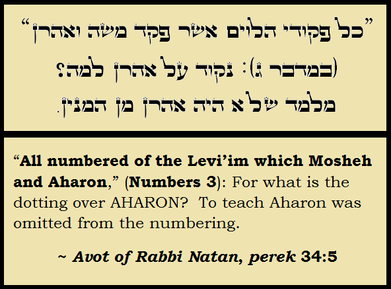

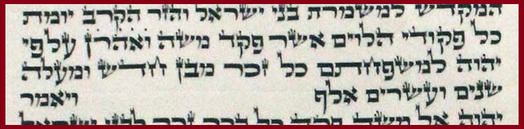

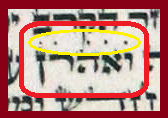

The niqqudot that we have seen in these several places in the book of Genesis are entirely absent from the books of Exodus and Leviticus. They pick back up in the book of Numbers 3:39. In this passage, the context revolves around the numbering of the children of Israel in the wilderness – and specifically in this verse, the numbering of the tribe of Levi.

All numbered of the Levi’im which Mosheh and Aharon numbered at the mouth of YHWH, for their families – every male from the son of a month, and from above, were twenty and two thousand.

The Torah continues with the third time in a row that a word is entirely dotted – “and Aharon.”

The Jewish commentary on the matter, found in the Avot of Rabbi Natan, tells us this:

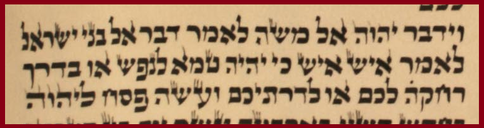

The next time we see a dot over a word in the book is Numbers 9:10. The passage discusses the allowance of keeping the Passover meal in the second month instead of the first for a person who is unable to observe it initially because of certain conditions.

Speak to the sons of Yisra’El, to say: “If a certain man of you or your descendants shall be unclean for a soul, or on a way that is distant, yet shall he perform the Passover to YHWH.”

This instance marks a return to merely one letter in a word being dotted the Heh in the term REKHOQAH - "distant."

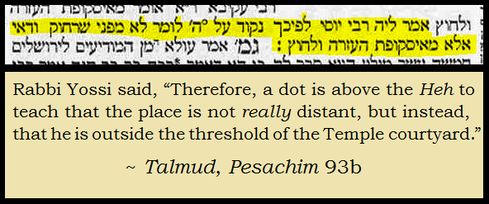

The Talmud Bavli, in Pesachim 93b, tells us that the dot here signifies that the allowance extends to anyone beyond a certain point in the Temple!

Another dot is found in Numbers 21:30. The placement of this one is in a proverb given concerning the retelling of some of Israel’s warfare conquests while in their wilderness journey.

And we shot at them; Kheshbon has been destroyed unto Divon, and we desolated them unto Nofakh, which is unto Meydeva.

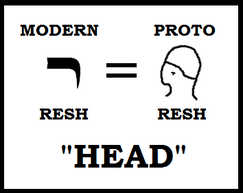

The term containing the dot in this passage is “which,” being the Hebrew word ASHER. The dot is over the letter Resh in the term.

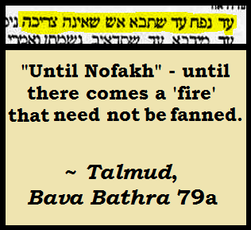

The Talmud Bavli, while it does not explicitly reference the dot found here, does touch upon it in a round-about manner in its comment in Bava Bathra 79a, where it tells us this interesting tidbit:

This comment is made by taking into account the dot over the Resh, and in doing such, reading the word ASHER as if it did not contain the Resh, so that the resulting term is EYSH, meaning “fire.”

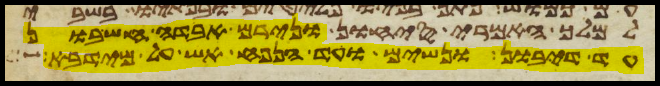

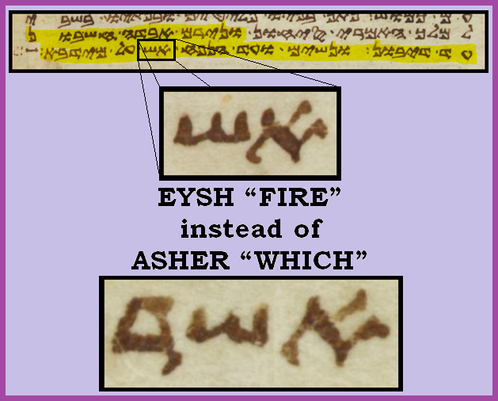

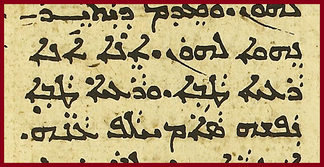

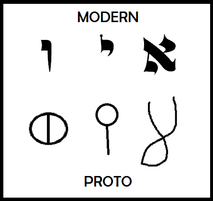

Astonishingly, this is also one time where the Jewish Talmud essentially quietly promotes a reading from the Samaritan Torah over the accepted form of Torah as preserved by the Jewish people, for the Samaritan Torah actually has the word EYSH instead of ASHER in this very verse! I have highlighted the verse from this manuscript dated to the 11th century because the Samaritan form of Paleo-Hebrew is quite different than the recognizable “Jewish” form.

The word in the Samaritan Torah, just like in the Talmud Bavli, is EYSH – “fire,” rather than the traditional Torah’s form of ASHER – “which.”

In contrast, the Avot of Rabbi Natan ignores the Talmud’s reasoning and offers a totally different interpretation of the dot.

The idea behind the comment is that the letter Resh that is dotted literally means “head” in the ancient Proto-Semitic glyph version of the Hebrew alphabet.

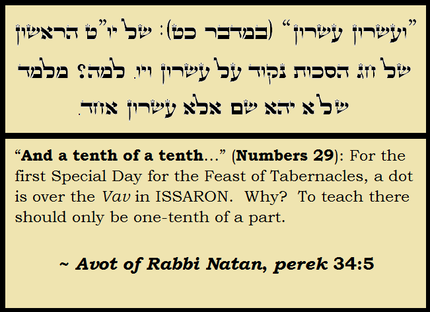

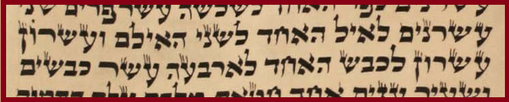

The ninth dot in the Torah is found in Numbers 29:15. The context is the offering schedule for the last feast of the year commanded by the Most High – Sukkot / Tabernacles.

And a tenth of a tenth for each lamb of the fourteen lambs.

The Hebrew word over which the dot is found is ISSARON, meaning “a tenth.”

The Avot of Rabbi Natan again attempts an answer for the presence of the dot, which offers but little further clarity.

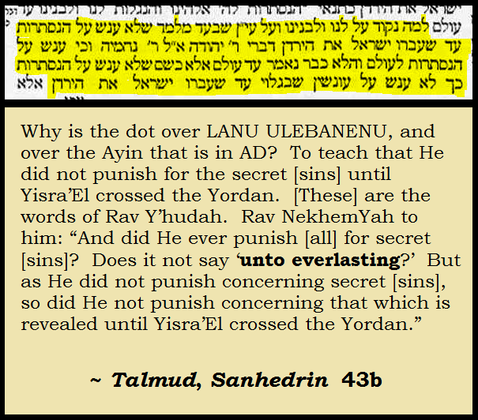

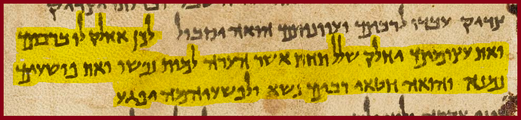

The final set of niqqudot that appear in the Torah are located in Deuteronomy 29:28 (29:29 in English versions). The context in this passage regards Moses telling the people of Israel a reminder of what has been done for them since being led out of Egypt, and how they are in covenant with the Holy One, and what that means for them.

The secrets are for YHWH our Deity, and the revelations are for us and for our sons unto everlasting, to perform all the words of this Instruction.

In this final instance of dots in the Torah, and the only appearance of such in the book of Deuteronomy, we have a phrase that has more niqqudot in one setting than anywhere else. Additionally, there are more niqqudot in this passage than all of the dots of Numbers put together! This also marks the only time in the Torah where multiple words are dotted in a passage. The phrase LANU ULEVANEYNU AD “for us and for our sons unto…” possesses niqqudot over every single letter in the Hebrew, except for the last letter of the word AD.

The reason for the strange use of dots is given an answer according to Judaism in the Talmud Bavli, tractate Sanhedrin 43b.

Concerted effort has been put forth thus far to show each instance of dots as it is in the Torah, and to display honestly the disharmonious views of Judaism on the meaning of the niqqudot as they appear variously in their locations in the scroll of Torah. The reason for this is that I do believe that these points in the text are meaningful, and yet I also believe that the true spiritual intent behind them has largely been missed by the rabbis and commentators, despite points made here and there that could be said to be of interest.

It is my view that the meaning of these dots in the scroll of Torah is eminently spiritual, and that their purpose is absolutely connected from beginning to end. Therefore, I will now present my perspective of their significance with the hopes to unify their presence in the text in the most basic way possible, but also with the result of imbuing them with the most meaning.

To truly understand the use of the niqqudot, I believe that we must look at the very meaning of the term giving these dots, for in that lay the key to unlocking their presence in the text.

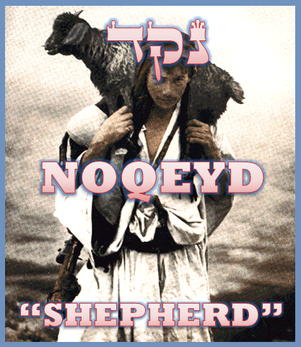

The Hebrew word NIQQUDOT, while being translated as “dots” / “points,” comes from the root word of NAQAD, which literally means “to be pierced.” The connection to “dot” is that in the result of the NAQAD, in the piercing action, a “mark” or “dot” is left.

With this definition, I propose that a spiritual intent is at work in the placing of the niqqudot in the text of the Torah – the dots are really meant as “piercings” placed selectively and purposefully as the Spirit led the scribes. In this proposal of meaning is embedded in hint the Person of the Messiah Yeshua, who was pierced for us! The piercings He experienced at His crucifixion were manifold: not only in hands and feet, but by the crown of thorns forced upon His skull, and the sword that plunged into His side after His death on the cross. He truly was ridden with niqqudot – piercings! The prophet Isaiah spoke of this horrifying reality in Isaiah 53:5.

And He was pierced for our iniquities, and broken for our perversities, and the correction of our peace was upon Him, and by His marks is healing for us.

When that spiritual view is obtained, we can look at the term of NAQAD in also another relevant manner. The exact same letters spell not only the idea of “pierced,” but also, if pronounced instead as NOQEYD, those three letters spell the seldom-used Hebrew word for “Shepherd!”

When that spiritual view is obtained, we can look at the term of NAQAD in also another relevant manner. The exact same letters spell not only the idea of “pierced,” but also, if pronounced instead as NOQEYD, those three letters spell the seldom-used Hebrew word for “Shepherd!”

This, too, also points us straight to the Messiah, who called Himself the Shepherd in the Aramaic of the book of John 10:11.

I am the good Shepherd, and the good Shepherd puts Himself in place of His flock.

Shepherds have a method of keeping track of which sheep are their own: through the use of marking fluid, or what is also known as “keel,” a colored applicant which is marked upon the animal’s head or back, and which immediately signals whether the specific creature belongs to them, or not. It is in this sense that the word for “Pierced,” came also to be used in Hebrew for “Shepherd” – NOQEYD: the “Marked One.”

In these two ways, the ancient use of niqqudot in the Torah, the original purpose of which has essentially been forgotten by even the very guardians of Torah for over two-thousand years, can now be seen to be appreciated as utterly unique symbols for the Messiah Yeshua, who, as the Shepherd laying down His life for the flock, would be pierced for their sake!

Let us now look briefly back over the ten passages in Torah with this newfound link of the niqqudot / piercings to the Messiah and see what these unified connectors have to show us!

Let us now look briefly back over the ten passages in Torah with this newfound link of the niqqudot / piercings to the Messiah and see what these unified connectors have to show us!

The first dot in Genesis 16:5 is over the letter Yod in the Hebrew word UVEYNEKA – “and between you.” Hagar conceiving was supposed to bring honor to Sarah, to yield the promised son, but the opposite was happening; Hagar was elevating herself above Abraham’s wife with her pregnancy. Sarah’s declaration is that the Holy One will judge between her and between Abraham, but we know that judgment does not come upon the believer in such a way. Rather, judgment was poured out upon the true Seed of Abraham – Yeshua. The judgment came upon Him instead of those who belong to the Holy One.

Note also that the word over which is the dot is unique: it is spelled with two letter Yods. The second appearance of the letter Yod – the one over which is the dot, is not normally written. In fact, so abnormal is it that this is the only time the word is ever spelled in the Torah in this manner! The importance of this in connection to the judgment of Messiah on the cross is that the letter Yod is anciently depicted as a hand, and over the Yod / hand is the NAQAD – the “piercing!”

The second instance of niqqudot in Genesis 18:9 is over the letters Alef, Yod, and Vav in the Hebrew word EYLAV – “unto him.” The angels are about to announce the imminent birth of the promised son to Abraham and Sarah, and in their speaking, they address the patriarch directly.

The dots over those three letters speak to the sacrificial nature of the son that would be born to him, whose life was a living symbol of the Son who would come – Yeshua, who Himself was to be the true sacrifice.

The third dotted place of Genesis 19:33 has a single dot over the Vav in the middle of the word UVEQUMAH – “and at her rising.” Although a scandalous deed in every respect, rectification began for the people of Moab (the name of the child conceived in this incestuous encounter) by the inclusion of Ruth into the Davidic kingly line so many generations after this event. Her joining to the people put Moab right into the lineage of the Messiah who was to be born.

Indeed, the very word for “resurrection” in Hebrew is TEQUMAH, which means “the rising.” It is essentially the word QUMAH with the letter Tav prefixed to it, so that “buried” in the resurrection is the “piercing” of the Messiah! The dot over the Vav at the center of this word is evidence that this was necessary in the grand act of redemption – the “piercing” above the letter hints that even this shameful deed was to be used for good in the masterful plan of the Most High. Out of the crucifixion for our sin there would be a righteous “rising” in the resurrection of the Pierced One!

The entire word of VAYISHAQEYHU “and he kissed him,” that is in Genesis 33:4, has dots over the Hebrew letters. In this, the commentators of Judaism were seeing something of merit, in that they said variously that the kiss was either “insincere,” or else that Esau intended to really “bite” Jacob. The root meaning of the niqqudot “piercings” over the word may well have guided that initial idea.

The link with the “piercings” and to the “Shepherd / Pierced One” in this is clearly that of the insincere kiss of Judas given to Yeshua which started the gears turning to the evil machinations that led to His crucifixion, as recorded in the book of Luke 22:47-48.

The link with the “piercings” and to the “Shepherd / Pierced One” in this is clearly that of the insincere kiss of Judas given to Yeshua which started the gears turning to the evil machinations that led to His crucifixion, as recorded in the book of Luke 22:47-48.

47 And while He was speaking, see, a crowd, and he who was called Yeehuda, one from the twelve, came before them. And he drew near to Yeshua, and kissed him, for this was the sign he gave to them, “Who I kiss is He.”

48 Yeshua said to him, “Yeehuda, with the kiss you deliver up the Son of Man?”

The parallel is quite strong in this instance; the kiss is highly prophetic of the One who would die for even those who were His enemies. The niqqudot over the “kiss” of Esau thus are prophetically placed to call to mind the same insincere kiss of Judas who would bring about the piercing of Yeshua.

In an unusual turn of events, the untranslatable word ET has dots over both letters in the word in the Hebrew of Genesis 37:12, when the text tells us the sons of Jacob go to Shekem to shepherd his flock. The Jewish commentators said the dot intended that they were derelict shepherds in their duty, and went rather to attend to their own desires. Thus, the ET could be viewed as being “absent” from their actions – it showed there was no direction / purpose in their shepherding.

This instance of the “piercings” that appear over the letters Alef and Tav of the ET links us to the Messiah, who, as the Shepherd who would lay down His own life for the flock, as seen previously in John 10:11, points us to the events of John chapter 4:4-43, where Messiah goes to this very place where Jews otherwise refused to travel, to the ancient well located there from whence the sons of Jacob had once watered those flocks, and meets a Samaritan woman – a person of a different “flock,” whom He immediately begins to “shepherd” into the truth of the hope for redemption. The Jews had no dealings with Samaritans, and the niqqudot of Genesis 37:12, indicating that the sons of Jacob also neglected their duties in that area, show the original seed of that abandonment of being a light in the world.

The ET is linked beautifully to the Messiah Yeshua, in that it is made of the first and the last letters of the Hebrew alphabet (just as the book of Revelation calls Messiah the “Alpha and Omega” in Greek translations, the Aramaic translations instead use the phrase “Alef and Tav”), and as it appears next to the term ELOHIM (Deity / G-d) in Genesis 1:1, is the term referenced by John in chapter 1:1 of His Gospel, linking it straight to the Messiah.

The ET is linked beautifully to the Messiah Yeshua, in that it is made of the first and the last letters of the Hebrew alphabet (just as the book of Revelation calls Messiah the “Alpha and Omega” in Greek translations, the Aramaic translations instead use the phrase “Alef and Tav”), and as it appears next to the term ELOHIM (Deity / G-d) in Genesis 1:1, is the term referenced by John in chapter 1:1 of His Gospel, linking it straight to the Messiah.

The phrase VE’AHARON “and Aharon” in Numbers 3:39 contains over it niqqudot. These dots are said by the rabbis to reflect that although the Levites were counted in this enumeration, and Aharon himself was a Levite, that the Holy One had them leave out the high priest from the count, so that he was not numbered with his brothers.

The niqqudot that appear here – the “piercings” above his name, are hints at the High Priest who was to come – Yeshua the Messiah, who would be pierced for us! He would be a priest after a different order than his Levite countrymen: Yeshua would be a priest after the order of which Melchisedek was priest – a ministry that placed him outside, yet above, the Levitical order. His role would be intercessory, but also self-sacrificial, as the book of Isaiah 53:12 tells us would be the case.

The niqqudot that appear here – the “piercings” above his name, are hints at the High Priest who was to come – Yeshua the Messiah, who would be pierced for us! He would be a priest after a different order than his Levite countrymen: Yeshua would be a priest after the order of which Melchisedek was priest – a ministry that placed him outside, yet above, the Levitical order. His role would be intercessory, but also self-sacrificial, as the book of Isaiah 53:12 tells us would be the case.

Therefore, I shall apportion for Him with the great, and [with] the powerful He shall apportion the plunder, because of which He laid bare unto death His soul, and was numbered with the iniquitous, and the sins of many he lifted, and for the iniquitous interceded.

Messiah was not counted among His people as an intercessor, but was left out of the enumeration of the holy ones. His piercing was for the intercession of the people of the Most High, just as the piercing of Aharon meant that he still had a purpose among them as high priest.

There is a single dot over the letter Heh in the word REKHOQAH “distant” in Numbers 9:10, which speaks of the allowance to observe the Passover in the second month if unable to do so in the first should a person be unclean or far away. The letter Heh in the ancient Proto-Semitic Hebrew script was a rudimentary depiction of a stick figure of a man, and that concept likely was preserved sufficiently enough through the centuries to yield the reason the rabbis gave for the dot over this letter: that it was really a “man” who was distant in his heart, which led to him being “distant” in not performing the Passover.

The “piercing” that appears over it in the Torah is telling. It points us to the Messiah on the cross, who, although just yards outside of Jerusalem during the feast of Passover, felt unfathomably distant from the Presence of the Holy One as the sacrifice of the true Lamb was being made. His cry from the cross in Matthew 27:46 says it all.

And facing the ninth of the hours, Yeshua cried out with a loud voice, and said, “Deity! Deity! For what have You left Me?”

In the word ASHER – “which” that is in Numbers 21:30 is found a dot above the letter Resh. This appearance is of interest in that the letter Resh, as discussed previously when giving the rabbi’s take on this particular dot, is anciently depicted as a “head.” Above the “head,” therefore, is a “piercing” in the presence of the dot.

There is a beautiful imagery here. Obviously, this would make one think of the head of Yeshua when it is pierced by the crown of thorns. Such an event, as described so vividly by Isaiah 53:5, brings healing.

There is a beautiful imagery here. Obviously, this would make one think of the head of Yeshua when it is pierced by the crown of thorns. Such an event, as described so vividly by Isaiah 53:5, brings healing.

And He was pierced for our iniquities, and broken for our perversities, and the correction of our peace was upon Him, and by His marks is healing for us.

However, there is further link to the healing brought to men by Yeshua. In John 5:2-9, we read of the account of the lame man at the pool of Bethesda, who spoke of an angel who would come and trouble the otherwise calm waters of the pool, and the first to enter would receive healing of their ailment. Due to his particular physical limitations, he was never quick enough to descend into the waters while they were moved, and so healing was always out of reach for him. In a beautiful turn of events, though, we find that Messiah, coming to him between the angelic movement and still water, decides to heal him with His very word.

2 Yet, there was at Urishlem one place of washing that was called in Ebra’ith ‘Beth Khesda,’ and there is in it five porches.

3 And in these were place many people of infirmities, and blind, and lame, and withered, they were hoping for the moving of the waters,

4 for a messenger at certain times descended to the washing [place], and moved the waters for them, and whomever was first from after the moving of the waters was healed of any sickness that he had.

5 Yet, there was one man that for thirty and eight years had an infirmity.

6 This [one] Yeshua saw, who was laying, and He recognized he was there for many seasons, and He said to him, “Do you desire to be healed?”

7 He who was infirm replied, and said, “Yes, my Master, but for me is no man who, when the water is moved, shall put me in the washing [place], but that while I am coming, another descends from before me.”

8 Yeshua said to him, “Stand! Take up your bed, and walk!”

9 And in the son of an hour the man was healthy. And he rose, took up his bed, and walked. And that day was the Sabbath.

What is amazing is how the above account links to the passage with the dot, in that the terms that surround the Hebrew word ASHER, over which is the dot in the Hebrew of Numbers 21:30, are entirely significant to the above encounter: just before ASHER is the word NOFAKH, which means “breath,” and immediately after ASHER is the word MEYDEVA, which means “calm water.” It was the word / breath of the One whose head would be pierced for our healing that brought healing for the lame man while the water was still calm and unmoved by the angel!

A single dot is found in Numbers 29:15 over the letter Vav in the word ISSARON – “a tenth” in regards to the meal offering to be presented with the lambs on the first day of Sukkot – the feast of Tabernacles. The word is repeated in this verse, and Judaism said the dot is merely to indicate that the word is only meant to be understood once. However, this explanation really doesn’t make much sense in that the exact same repetition in Hebrew appears just a few verses before in regards to Yom Kippurim – the Day of Atonements, in 29:10, and in that occurrence, no dot is found.

In both instances of 29:10 and 29:15, the two repeated words are spelled identically, but only in 29:15 is one word given a dot over a Vav. The reason this is done only on the first special day of Sukkot / Tabernacles is that it points us to the offering of the Messiah Yeshua, of whom Scripture distinguishes was actually born on this very feast! [For more on this topic, see my study: A TABERNACLES NATIVITY.]

Notice that this offering is done with fourteen lambs, which aligns with a curious number that is repeated three times in Matthew chapter 1, where the lineage of the Messiah is given in three sets of fourteen. This “piercing” / dot links the fourteen special offerings presented in the Tabernacle on the first day of Sukkot straight to the birth of Yeshua, the One born during the same festival after three sets of fourteen generations, all to be pierced for us!

The final set of dots is in Deuteronomy 29:28 over the words LANU ULEVANEYNU AD – “for us and for our sons unto.” However, when it gets to the word AD “unto,” the dot ends with the Ayin, and the Dalet that finishes the word AD doesn’t have one.

This is very strange, and does well to convince anyone saying the niqqudot merely mark words and letters that are in error that such a proposal is wrong, for if these dotted words and letters were removed, the text would have an isolated letter Dalet interrupting the flow of the Hebrew passage, which makes no sense.

What, then, is the purpose of the niqqudot over this phrase in the Torah? It is to teach us the “piercing” of Yeshua is for the sons of the Kingdom – Israel and all who are grafted into the people through the Messiah – “for us and for our sons…”

Additionally, the absence of a dot over the last letter of AD, a word which can mean “forever” as well as “unto,” is to signify that the Kingdom of the Pierced One will be without end – everlasting. The Ayin is the eye – the eye sees forever when we look into the heavens, and in similar sense, the “eye” here has the NAQAD over it to show that there is no ending to the Kingdom that is coming – the kingdom of Yeshua the Messiah!

This is very strange, and does well to convince anyone saying the niqqudot merely mark words and letters that are in error that such a proposal is wrong, for if these dotted words and letters were removed, the text would have an isolated letter Dalet interrupting the flow of the Hebrew passage, which makes no sense.

What, then, is the purpose of the niqqudot over this phrase in the Torah? It is to teach us the “piercing” of Yeshua is for the sons of the Kingdom – Israel and all who are grafted into the people through the Messiah – “for us and for our sons…”

Additionally, the absence of a dot over the last letter of AD, a word which can mean “forever” as well as “unto,” is to signify that the Kingdom of the Pierced One will be without end – everlasting. The Ayin is the eye – the eye sees forever when we look into the heavens, and in similar sense, the “eye” here has the NAQAD over it to show that there is no ending to the Kingdom that is coming – the kingdom of Yeshua the Messiah!

These ten sections in the Torah all preserve the ancient niqqudot for a spiritual purpose. The witness of the rabbis throughout the centuries displays that they have existed in the scroll from antiquity, but the purpose is one they disagreed upon over and over again. The reason they could not come to agreement on their significance is that they were not viewing the niqqudot in their most basic meaning – piercings. When the root idea of the niqqudot is inserted into the context of their appearance in the text, they all begin to convey deep links to the Messiah Yeshua, whose sacrifice for His people has not yet been fully appreciated by all Israel. The day is coming, though, when all His people will connect the dots, and see Yeshua as the true Shepherd of Israel!

All study contents Copyright Jeremy Chance Springfield, except for graphics and images, which are Copyright their respective creators.