THE TRUTH OF THE WHEAT & TARES

by Jeremy Chance Springfield

6/17/2023

The ministry of Yeshua is particularly famous in his use of parables. Making sure that the uneducated public received Torah-based teaching was a prime concern for the Messiah, and He delivered that to them through unique allegories. Unlike so many of His rabbinic colleagues, Yeshua focused His transmission of the Torah’s eternal truths to an audience of the every man. He did not restrict the general applicability of our Creator’s words to the privacy provided by Pharisaic schools, but openly shared His wisdom with those who would not typically be accepted in Hillel’s hallowed halls.

This decision to impart truth He undertook with great responsibility, however. His method of delivery meant that those who received the information evaluated it based on their personal level of insight and understanding. Yeshua’s system of sharing in parables entailed that the details were assessed by the public in various degrees of comprehension.

He taught the public in essentially the same wise manner as his ancestor, King Solomon. That son of David used the vehicle of parables in a far more succinct manner of a sentence or two—recognized now under the title of “proverbs”—and yet the Hebrew term for “parable” and “proverb” is one and the same: MASHAL.

He taught the public in essentially the same wise manner as his ancestor, King Solomon. That son of David used the vehicle of parables in a far more succinct manner of a sentence or two—recognized now under the title of “proverbs”—and yet the Hebrew term for “parable” and “proverb” is one and the same: MASHAL.

A proverb is merely a parable scaled down in length. Both deliver a spiritual truth of the Torah in a form that can be accessible to those possibly not prepared for such a spiritually direct approach as is presented in the Torah.

Either way, the truth is being shared, and that is what is important. To this end, one of Yeshua’s most famous parables is that of the sower recorded in Matthew 13. It has been focused upon for good reason by countless minds, and yet, its presentation serves as just the tip of the iceberg for a series of additional parables that are also presented in an agricultural setting. Immediately following the parable of the sower and the disciple’s semi-private question of why He taught in the elusive, layered manner of parables, Yeshua resumes His teaching of the crowd with the second of the agriculturally based parables.

Either way, the truth is being shared, and that is what is important. To this end, one of Yeshua’s most famous parables is that of the sower recorded in Matthew 13. It has been focused upon for good reason by countless minds, and yet, its presentation serves as just the tip of the iceberg for a series of additional parables that are also presented in an agricultural setting. Immediately following the parable of the sower and the disciple’s semi-private question of why He taught in the elusive, layered manner of parables, Yeshua resumes His teaching of the crowd with the second of the agriculturally based parables.

He presents what is known as “the parable of the wheat and tares.”

Tares are not intended for human consumption. Based on the 1902 research of E.M. Freeman, M.S., we know that the plant possesses a toxicity due likely to the symbiotic presence of a fungus pervading both fruit and body of the ryegrass, making it inedible to humans and even grazing herds. The presence of it mixed into a field intended to yield a valuable crop was disastrous.

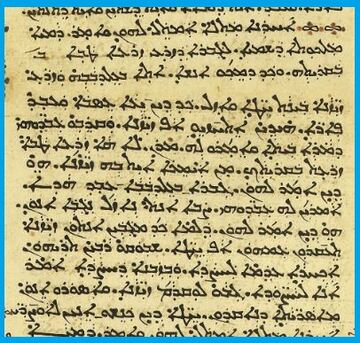

The Greek term that is used for “tare” in Matthew 13 is ZIZANIA, which does not provide the reader with really any further source of insight to the topic, as Biblical Greek scholars admit its origin language is unknown. A better route to understanding the term only comes from looking at it as it is found in the Aramaic of the Peshitta. There the word for “tare” is ZIZANA.

The Greek term that is used for “tare” in Matthew 13 is ZIZANIA, which does not provide the reader with really any further source of insight to the topic, as Biblical Greek scholars admit its origin language is unknown. A better route to understanding the term only comes from looking at it as it is found in the Aramaic of the Peshitta. There the word for “tare” is ZIZANA.

To be sure, the Aramaic ZIZANA is essentially the same word as the Greek’s mysterious ZIZANIA. The reason why looking at the Aramaic is important is that the term in Aramaic stems from the root word of ZIZ, meaning both “an attachment,” and “a mite.”

The reason this is significant is in its apparent connection to the notion of a fungus that grows in symbiotic relationship with the likeliest tare candidate of Lolium temulentum—“darnel ryegrass.” The fungus has somehow grown to attach itself to the species so as to be a beneficial addition to the plant. The “mite” connection to the fungus is such that the ZIZ root word refers to a very small mite that is known to infest lentils, as discussed in the Talmud Yerushalmi, Terumot 8:1, and in the Talmud Bavli, Chullin 67b. Therefore, through the ZIZ root we have both of its main meanings seeming to fit the fungal-infection situation of ZIZANA / ZIZANIA: a plant rendered toxic by the attachment of an outside living entity. This route of understanding also seems to support the Hebrew term used for “tare,” which is ZONEH.

The Hebrew term of ZONEH for “tare” yields its own similar path of insight in that the word originates with the root of ZONAH, meaning “prostitute.”

From this we can also appreciate the Aramaic route’s notions of “attachment” and “mite”—an unclean living thing feeding off something else. A prostitute is effectively engaged in those activities: attaching to someone else through a decidedly unclean method.

What this does is provide us with a better appreciation of the serious nature of tares and why they cannot be allowed to be consumed. They are effectively physical representations of a spiritual blight. They must be dealt with for what they represent. With this in mind, we can now present the parable of the wheat and the tares with the proper perspective to appreciate the further concepts which are embedded in the Aramaic text of the Peshitta.

The parable is given in Matthew 13:24-30.

What this does is provide us with a better appreciation of the serious nature of tares and why they cannot be allowed to be consumed. They are effectively physical representations of a spiritual blight. They must be dealt with for what they represent. With this in mind, we can now present the parable of the wheat and the tares with the proper perspective to appreciate the further concepts which are embedded in the Aramaic text of the Peshitta.

The parable is given in Matthew 13:24-30.

24 Another parable he allegorized for them, and said, “The Kingdom of the heavens is likened to a man who sowed good seed in his field,

|

25 and when men slept, his enemy came and sowed darnel ryegrass among the wheat and left.

26 Yet, when the plant sprouted and made fruits, then darnel ryegrass was even seen! 27 “And the laborers of the master of the house drew near and they said to him, ‘Our master! Did you not sow good seed in your field? From where is darnel ryegrass in it?’ |

28 Yet, he said to them, ‘A man—the enemy—did this.’ The laborers said to him, ‘Are you desiring that we go and gather them up?’

29 Yet, he said to them, ‘Perhaps when you gather up the darnel ryegrass you shall uproot with them also the wheat?

30 You must leave the two to grow as one until the harvest. And in the season of the harvest I shall say to the reapers: “You must gather first the darnel ryegrass, and you must tie them in sheaves that they shall be burned. Yet, the wheat you must amass for my storehouse.”’”

29 Yet, he said to them, ‘Perhaps when you gather up the darnel ryegrass you shall uproot with them also the wheat?

30 You must leave the two to grow as one until the harvest. And in the season of the harvest I shall say to the reapers: “You must gather first the darnel ryegrass, and you must tie them in sheaves that they shall be burned. Yet, the wheat you must amass for my storehouse.”’”

The explanation for the parable is presented several verses later, but before we get to that, it is important to note several nuances in the Aramaic text that will help us better understand what is included in Yeshua’s words.

First, note that both wheat and tares were sown in the same field—albeit not intentionally by the owner of the field. This reality, however, is still something that must be addressed that is left unspoken in the parable. The reason is that the Torah forbids two different seed types from being sown in the same field, as commanded in Leviticus 19:19, which says:

First, note that both wheat and tares were sown in the same field—albeit not intentionally by the owner of the field. This reality, however, is still something that must be addressed that is left unspoken in the parable. The reason is that the Torah forbids two different seed types from being sown in the same field, as commanded in Leviticus 19:19, which says:

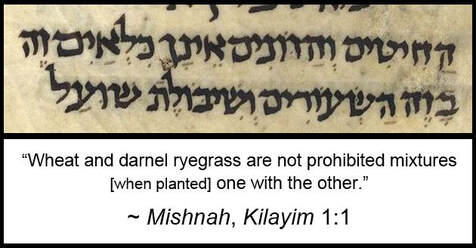

Yeshua’s unabashed allowance for wheat and tares to be grown together in the parable appears to apparently be a sentiment that is in direct violation of the Torah’s prohibition of sowing two different seeds together in the same field. This constitutes a problematic situation for the reader, it seems, but this is only an issue if one does not know about the clarification that is preserved in the text of the Mishnah, Kilayim 1:1.

It was understood by Torah-sanctioned judges of ancient Israel that these two species that were similar in many ways—yet totally distinct in terms of human usage—would not constitute a breaking of the Torah if they were sown together in the same field. This detail from Jewish history reveals that Yeshua was indeed familiar with the Oral Torah of His time and recognized it and validated its ruling by the content of His own teaching. This is just one example from many in the New Testament of why it is vital for the reader to be educated in the Oral Torah, for it does factor into aspects of what is contained in the words of the Messiah and His original followers and impacts how we perceive what has been preserved in them. Without a knowledge of such parallels to and obvious dependency on the Oral Torah, the believer is exposed to the text of the New Testament being honestly misinterpreted or having their faith attacked by those exhibiting malicious attempts to discredit their trust in the validity of its content.

This brings us to the next detail of note in the Aramaic text.

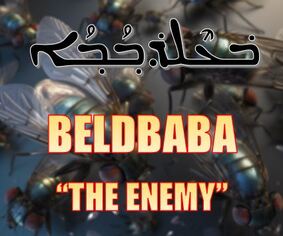

Consider in Matthew 13:28 that the undesirable plants are said to have been sown by someone quite specific: “A man—the enemy—did this.” Yeshua’s clever construction says first that a “man” was responsible for the disastrous planting, and then qualifies that reading by saying an “enemy” did it. The Aramaic of the Peshitta provides clarity on what he meant, using the term Beldbaba for “enemy.”

This brings us to the next detail of note in the Aramaic text.

Consider in Matthew 13:28 that the undesirable plants are said to have been sown by someone quite specific: “A man—the enemy—did this.” Yeshua’s clever construction says first that a “man” was responsible for the disastrous planting, and then qualifies that reading by saying an “enemy” did it. The Aramaic of the Peshitta provides clarity on what he meant, using the term Beldbaba for “enemy.”

The term Beldbaba originated first as Belzbub, which comes from the older Hebrew pronunciation of Ba’al Zevuv—“The Master of the Fly,” recognized more popularly in its Anglicized form of Baalzebub and the moniker “Lord of the Flies.”

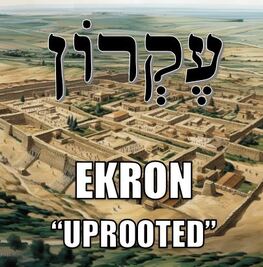

This was the title for the idol worshipped by the Philistines whose temple stood in the city of Ekron, as we see from the chronicle of the Israelite King Ahaziah’s injury and seeking of help from an idolatrous source, recorded in 2nd Kings 1:2.

The text is silent on the nature of King Ahaziah’s illness, but the text relates it to his fall from a supposedly significant height. Something must have caused the king to stumble or lose balance to fall through a lattice to the ground below, and in the process of it all he was injured severely. Based on his desire for healing from the idol of Baalzebub, who was viewed as being the protector of the scourge of disease-bringing flies (as the Hebrew of Ecclesiastes 10:1 seems to suggest ZEVUVEI MAVET to be read better as: “flies of death” rather than the more typically rendered: “dead flies”), the implication is that his fall resulted in an injury that perhaps brought with it an open wound and the presence of swarming flies and their unwanted diseases. Whatever the case may have been, it is evident that Baalzebub was viewed as sufficiently worthy to seek help from in flagrant opposition to the Torah’s prohibition against idolatry.

Baalzebub’s temple was at a place called Ekron—one of the five major cities of the Philistines, just across their borders and west of Jerusalem. Ekron was notable as the limit to which the Israelites pursued the Philistines after the momentous defeat of Goliath by the young David in 1st Samuel 17:52. For an Israelite king to seek divine help from the principle idol of that city was especially an affront to the victories experienced by the holy people in the days of his ancestors.

Baalzebub’s temple was at a place called Ekron—one of the five major cities of the Philistines, just across their borders and west of Jerusalem. Ekron was notable as the limit to which the Israelites pursued the Philistines after the momentous defeat of Goliath by the young David in 1st Samuel 17:52. For an Israelite king to seek divine help from the principle idol of that city was especially an affront to the victories experienced by the holy people in the days of his ancestors.

As time passed and worship of the idol diminished until it apparently passed away, the name Baalzebub was preserved but was applied anew by the Jewish population to refer instead to a demon. In the New Testament texts in particular, the view was that it referred to the “ruler” of all the demons--Satan himself. This sentiment can be found in Matthew 12:24; Mark 3:22; and Luke 11:15. In fact, this parable was stated later on the exact same day Yeshua was accused by the Pharisees of casting out demons by the power of Baalzebub, as Matthew 12:24 and Matthew 13:1 reveal! The veiled allusion to Baalzebub through His use of the term Beldbaba is therefore absolutely intentional!

The change from the pronunciation of Ba’al Zevuv to Beldbaba lay in the Aramaic interchange of certain letters when transitioning from Hebrew into its sister tongue. In particular, the letter Zayin (Z) often interchanges with the letter Dalet (D), which is what we find to have happened in this situation. One of the most commonly encountered examples of this sort would likely be between the Hebrew ZAHAV “gold” and the Aramaic DEHAV “gold.

The change from the pronunciation of Ba’al Zevuv to Beldbaba lay in the Aramaic interchange of certain letters when transitioning from Hebrew into its sister tongue. In particular, the letter Zayin (Z) often interchanges with the letter Dalet (D), which is what we find to have happened in this situation. One of the most commonly encountered examples of this sort would likely be between the Hebrew ZAHAV “gold” and the Aramaic DEHAV “gold.

In short, Beldbaba is merely another form of Belzbub in Aramaic, aka Ba’al Zevuv in Hebrew, aka Baalzebub in Anglicized English. Over time, the pronunciation of Beldbaba lost its distinct spiritual connotation and became specifically used to speak of just an “enemy” in general. The original demonic spiritual concept, however, is the hidden intended meaning by Yeshua in the parable, as its eventual explanation from His own words will reveal. The hint is only preserved in the Aramaic texts of the Peshitta, however, which serves again to show how important it is to read the text with its Semitic background intact to catch as much as possible the plays on words that affect proper interpretation.

The workers ask if the field’s owner desires for them to set to work clearing the tares from the field, and then in 13:29, he responds that if they should undertake such an endeavor they might just unintentionally uproot some of the wheat crop, as well. The reason for this concern is not that the workers are inexperienced in the act of culling, but it rather lay in the physical similarity shared between immature wheat and tares.

The appearance of Lolium temulentum “darnel ryegrass” is nearly identical to that of cultivated wheat during its initial growth stages. The fact that their time of maturation from seed to fruiting body is essentially the same as that of wheat does not help the situation. Only when tares fruit with grains in their head do they truly stand out as a distinctly different species from the valuable wheat. Whereas wheat in its fruiting stage contains grains heavy enough to bend the stem over so that it appears, in a sense, to be bowing in the field, the different nature of the tares produces lighter heads of grain that remain growing upright. This detail would provide the reapers with a clearly visible distinction between the wheat and the tares. Therefore, waiting until the time of harvest would allow the workers to safely remove the undesirable inedible growth from the valuable crop of wheat.

The workers ask if the field’s owner desires for them to set to work clearing the tares from the field, and then in 13:29, he responds that if they should undertake such an endeavor they might just unintentionally uproot some of the wheat crop, as well. The reason for this concern is not that the workers are inexperienced in the act of culling, but it rather lay in the physical similarity shared between immature wheat and tares.

The appearance of Lolium temulentum “darnel ryegrass” is nearly identical to that of cultivated wheat during its initial growth stages. The fact that their time of maturation from seed to fruiting body is essentially the same as that of wheat does not help the situation. Only when tares fruit with grains in their head do they truly stand out as a distinctly different species from the valuable wheat. Whereas wheat in its fruiting stage contains grains heavy enough to bend the stem over so that it appears, in a sense, to be bowing in the field, the different nature of the tares produces lighter heads of grain that remain growing upright. This detail would provide the reapers with a clearly visible distinction between the wheat and the tares. Therefore, waiting until the time of harvest would allow the workers to safely remove the undesirable inedible growth from the valuable crop of wheat.

The detail that tares would have been most evidently distinguishable from the wheat at harvest time is one that the enemy would have known. He would not expect the owner of the field to ever eat them. Rather, the enemy’s intent is revealed in the concern voiced by the owner: the evil intent was that the tares would actually be ordered to be uprooted prior to the harvest when they still very closely resembled the growing wheat. Dealing with the presence of the tares in this premature fashion would inevitably lead to the additional unintentional uprooting of some stalks of valuable wheat.

This is the actual purpose behind the enemy’s devious actions: the destruction of viable crop—that is, the destruction not of the wicked, but of the righteous as collateral damage in the process of handling the wicked. The owner of the field shows the care with which the Holy One views His people and the whole harvest that comes from His intentional sowing. The worry is thus not for the tares being present amidst the wheat, but rather it is concern for the presence of the wheat being unintentionally harmed if the tares are addressed before their fruit reveals them.

This is a key factor we should understand from the parable. The wheat cannot be uprooted under any circumstances.

This aspect is one that is actually hinted at by the presence of the Aramaic term Beldbaba “enemy” / “Master of the Fly.” Recall that Baalzebub was originally worshipped in the city of Ekron. Consider the meaning of the city’s name in its Semitic definition: “Uprooted.”

This is the actual purpose behind the enemy’s devious actions: the destruction of viable crop—that is, the destruction not of the wicked, but of the righteous as collateral damage in the process of handling the wicked. The owner of the field shows the care with which the Holy One views His people and the whole harvest that comes from His intentional sowing. The worry is thus not for the tares being present amidst the wheat, but rather it is concern for the presence of the wheat being unintentionally harmed if the tares are addressed before their fruit reveals them.

This is a key factor we should understand from the parable. The wheat cannot be uprooted under any circumstances.

This aspect is one that is actually hinted at by the presence of the Aramaic term Beldbaba “enemy” / “Master of the Fly.” Recall that Baalzebub was originally worshipped in the city of Ekron. Consider the meaning of the city’s name in its Semitic definition: “Uprooted.”

The genius of Yeshua is revealed in the parable when He cites the concern of the field’s owner that the premature removal of the tares would uproot also some of the wheat. The term Yeshua uses for the phrase “shall uproot” in the Aramaic of the Peshitta is TEKRUN.

This word is the exact same term as the name of the city of Ekron, with only the grammatical addition of the letter Tav at the beginning to change the spelling so as to conjugate it to a “shall happen” context. The link preserved in the Peshitta’s text shows that Yeshua was teaching this in Aramaic and veiling His words to conceal the deeper meaning of the parable.

It is only when a person manifests distinct fruits—that is—their actions, that we can rightly assess what kind of nature they have. Without discernment we risk uprooting something of value when tearing out what we deem is toxic. This requires care on our part.

This reality is highlighted also in the words of Yeshua, for he stated that the difference between the good and the bad would only be seen at harvest-time. Darnel ryegrass may look like wheat for a time, but once it is finally mature, it does not act like wheat. Wheat bends over. This is an aspect of the humility of those being transformed as opposed to the pride maintained in hearts who are deceiving or self-deceived. Ironically, it is the wheat that is bent over which shall eventually be raised from the earth in a desirable harvest and subsequently elevated further by careful processing and refinement into meal fit for human consumption—all while the unwanted imposter grain is identified for what it is and cast into fire.

It is only when a person manifests distinct fruits—that is—their actions, that we can rightly assess what kind of nature they have. Without discernment we risk uprooting something of value when tearing out what we deem is toxic. This requires care on our part.

This reality is highlighted also in the words of Yeshua, for he stated that the difference between the good and the bad would only be seen at harvest-time. Darnel ryegrass may look like wheat for a time, but once it is finally mature, it does not act like wheat. Wheat bends over. This is an aspect of the humility of those being transformed as opposed to the pride maintained in hearts who are deceiving or self-deceived. Ironically, it is the wheat that is bent over which shall eventually be raised from the earth in a desirable harvest and subsequently elevated further by careful processing and refinement into meal fit for human consumption—all while the unwanted imposter grain is identified for what it is and cast into fire.

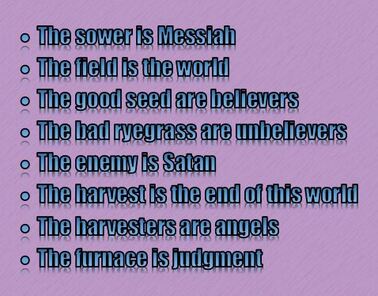

A few verses later, after the crowds have been dismissed, the disciples of Yeshua asked for clarity and receive an answer, as is chronicled in Matthew 13:36-43.

36 Afterwards, Yeshua left the congregants, and came to the house, and his students, they drew near unto him, and they said to him, “Explain for us the parable of the darnel ryegrass and of the field.”

37 And he replied, and said to them, “He who sowed good seed is the Son of Man,

37 And he replied, and said to them, “He who sowed good seed is the Son of Man,

|

38 and the field is the world. And the good seed are the sons of the Kingdom, yet, the darnel ryegrass are the sons of the Evil One.

39 And the enemy who sowed them is Satana, and the harvest is the completion of the world, and the harvesters are the angels. 40 As, therefore, the darnel ryegrass is collected and burned in the fire, so shall it be at the completion of this world. |

41 The Son of Man shall send for his angels, and they shall collect from his Kingdom all stumblers, and all working wrong,

42 and they shall cast them into the furnace of fire; weeping and grinding teeth shall be there.

43 Afterwards the righteous ones shall shine as the sun in the Kingdom of their Father. He who has for himself ears that he should hear, should hear.

42 and they shall cast them into the furnace of fire; weeping and grinding teeth shall be there.

43 Afterwards the righteous ones shall shine as the sun in the Kingdom of their Father. He who has for himself ears that he should hear, should hear.

Yeshua’s answer is straightforward. The explanation of the parable is as clear as it can be with all the symbolic features explained beautifully.

For as clear as the explanation is which Yeshua gave, it must also be acknowledged that He never elucidates the underlying notions which form the basis for this parable. These are found in the aforementioned record from 2nd Kings 1:2 and the account of King Ahaziah and his seeking of idolatrous treatment for the injuries he sustained when he fell from his upper chamber, whereupon he relied on sending messengers to Baalzebub at Ekron rather than trusting in the Holy One of Israel.

The account continues in 2nd Kings 1:3-17 to share the entire story. For the sake of brevity, the succinct sum of the story is that Elijah was sent by Divine command to pronounce judgment upon the king’s idolatry, telling the king’s messengers that he would die for his blatant sin. The king sends two bands of fifty soldiers and their captains to call Elijah to come to him. Both, however, meet their sudden end when fire falls from the heavens and incinerates them. It is only when a third group of fifty and their captain came and showed reverence for Elijah and the authority in which he acted that they were spared, and the prophet went with them to personally deliver his oracle to the ailing king, who eventually succumbed to his wounds without the benefit of whatever Baalzebub might have provided.

The account continues in 2nd Kings 1:3-17 to share the entire story. For the sake of brevity, the succinct sum of the story is that Elijah was sent by Divine command to pronounce judgment upon the king’s idolatry, telling the king’s messengers that he would die for his blatant sin. The king sends two bands of fifty soldiers and their captains to call Elijah to come to him. Both, however, meet their sudden end when fire falls from the heavens and incinerates them. It is only when a third group of fifty and their captain came and showed reverence for Elijah and the authority in which he acted that they were spared, and the prophet went with them to personally deliver his oracle to the ailing king, who eventually succumbed to his wounds without the benefit of whatever Baalzebub might have provided.

Let us bring this study to an end by appreciating the underlying thread that runs through Yeshua’s explanatory words as they are preserved in the Aramaic.

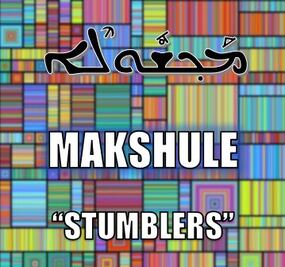

The tares, which represent the unbelievers, are collected and thrown into the furnace to be consumed. Yeshua specifically states that the tares which they gather are categorized by two distinct types:

“stumblers”

“all those working wrong”

The first term in the Aramaic is the word MAKSHULE, meaning “stumblers.”

The tares, which represent the unbelievers, are collected and thrown into the furnace to be consumed. Yeshua specifically states that the tares which they gather are categorized by two distinct types:

“stumblers”

“all those working wrong”

The first term in the Aramaic is the word MAKSHULE, meaning “stumblers.”

The sense of MAKSHULE could be two-fold: those things which make one stumble, and those people who are prone to stumbling. Either way, the link to King Ahaziah is clear: he who stumbled in some degree and accidentally fell through his lattice to be harmed in a mortal injury.

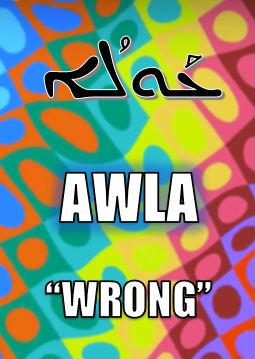

The second category includes “all who work wrong.” This idea Yeshua presented with the term AWLA, meaning “wrong,” a word that is rather generic in its sense of something that is negative in what it accomplishes.

The second category includes “all who work wrong.” This idea Yeshua presented with the term AWLA, meaning “wrong,” a word that is rather generic in its sense of something that is negative in what it accomplishes.

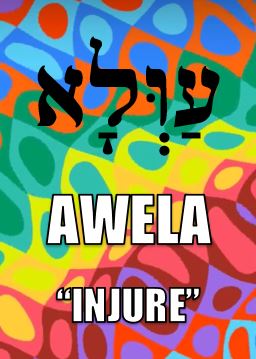

Without changing a single letter, the term can also be pronounced as AWELA, and in that sense, it distinctly means to “injure” something.

This meaning aligns perfectly with the context of King Ahaziah’s injury he sustained from his fall. However, the term AWLA is also closely related in phonetic pronunciation to the word OLAH, which means “burnt-offering.”

In this sense it is seen to be a hint to the nature of the fiery demise of Ahaziah’s messengers, as well as to the tares which are similarly offered to the furnace to be burned up.

We can see that Yeshua’s use of parables involved a rich connection to the Hebrew Scriptures and conveying the wisdom found therein to the people who would not normally glean the insights offered only to the dedicated students in the halls of Torah study schools. This specially crafted form of teaching brought the secrets of the Word in a veiled straightforward story, allowing even the least insightful listener something from which to draw inspiration and value, while simultaneously giving the more discerning among His listeners more to consider and mull over as they attempted to apply those eternal truths to their own walk of faith.

We can see that Yeshua’s use of parables involved a rich connection to the Hebrew Scriptures and conveying the wisdom found therein to the people who would not normally glean the insights offered only to the dedicated students in the halls of Torah study schools. This specially crafted form of teaching brought the secrets of the Word in a veiled straightforward story, allowing even the least insightful listener something from which to draw inspiration and value, while simultaneously giving the more discerning among His listeners more to consider and mull over as they attempted to apply those eternal truths to their own walk of faith.

The content of His parables was infused with layer upon layer of learning. Those allegories were accessible to all manner of interested person. Anyone with ears to hear could perceive in them something of value, and even today we are still mining from Messiah’s words precious gems worth the effort to polish and hold up to the light of our Father’s Word, seeing in them ever new facets that build our faith in the gift He has given to His people. May we have ears to hear and eyes to see it all!

All study contents Copyright Jeremy Chance Springfield, except for graphics and images, which are Copyright their respective creators.