OF SUCH IS THE KINGDOM

by Jeremy Chance Springfield

7/4/19

The ministry of the Messiah saw Yeshua encountering the spectrum of the human experience: kings, rulers, priests, men, women, and even children. He dealt with them all in unique approaches that spoke to the moment at hand – a personal witness to the coming Kingdom of Heaven in each event. Whether it was a luminous teaching moment, an edifying expression of encouragement, a fiery judgment against hypocrisy, or a multi-layered parable wreathed in wit, the words of the Messiah hold Kingdom value one and all. They are a mine of every precious spiritual metal, the path of which leads not into earthly depths, but ascends instead into the throne-room of Heaven itself. Even the most obvious of His words are worth careful consideration.

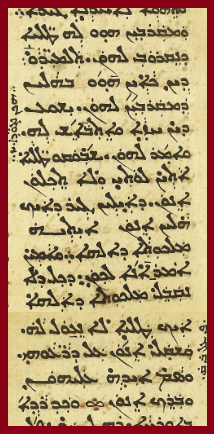

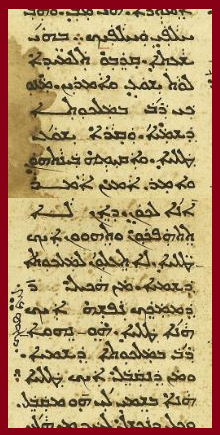

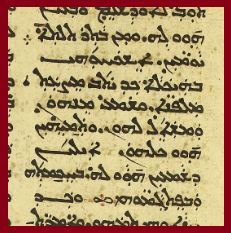

Let us take, for example, the straightforward declarations Yeshua made concerning an incident involving the presence of children during His ministering which is recorded in three of the Gospel accounts. While the event is preserved in Matthew 19:13-15, and in Luke 18:15-17, let us turn to the way Mark chose to render those words in the Aramaic of the Peshitta, as recorded in 10:13-16 of his Gospel.

Let us take, for example, the straightforward declarations Yeshua made concerning an incident involving the presence of children during His ministering which is recorded in three of the Gospel accounts. While the event is preserved in Matthew 19:13-15, and in Luke 18:15-17, let us turn to the way Mark chose to render those words in the Aramaic of the Peshitta, as recorded in 10:13-16 of his Gospel.

13 And they drew near youths to Him, that He should touch them, yet, His students, they reproved those who drew them near.

14 Yet, Yeshua saw, and it was offensive to Him, and He said to them, “You must allow the youths to come unto Me, and you shall not restrain them, for of those that are as these is the Kingdom of Alaha!

15 Surely I say to you that any who shall not receive the Kingdom of Alaha as a youth shall not enter it!”

16 And He took them upon His arms, and placed His hands upon them, and blessed them.

This incident serves to show that Yeshua cared even for children in His midst who were otherwise being viewed by His students as wastes of time. Those students did not hold these youths to be of any significance in the scheme of His teaching ministry. Because of this, they acted and attempted to prevent these children from interacting in the very important topics of faith that were taking place. In fact, Matthew and Mark both record for us that one of the discussions occurring immediately before this account had to do with the subtleties of the Torah concerning marriage and divorce, which involved Yeshua pronouncing His perspective on the issue based on careful attention to the way the Word speaks about marriage. Luke’s account of this event is prefaced by another detail in a similar context – the nuances of how a judge in Israel would treat a bothersome matter that kept resurfacing and would not go away.

These contexts display the serious nature of the teaching environment the students of Messiah were immersed in every day during the traveling ministry of Yeshua. Their rabbi was addressing complex and weighty matters of the Word at seemingly every turn, and so, in their opinion, the presence of children in these situations would at best be over their heads and so pointless to attend, and at worse, could likely be distracting to the adults who were involved and understood the significance of the issues being discussed. Thus, their actions of reproof towards those bringing youths into the zealous and often heated religious circle make complete sense when considered from how they viewed the matter.

Yeshua, on the other hand, was of a very different opinion.

These contexts display the serious nature of the teaching environment the students of Messiah were immersed in every day during the traveling ministry of Yeshua. Their rabbi was addressing complex and weighty matters of the Word at seemingly every turn, and so, in their opinion, the presence of children in these situations would at best be over their heads and so pointless to attend, and at worse, could likely be distracting to the adults who were involved and understood the significance of the issues being discussed. Thus, their actions of reproof towards those bringing youths into the zealous and often heated religious circle make complete sense when considered from how they viewed the matter.

Yeshua, on the other hand, was of a very different opinion.

He had no desire to see the children escorted away from the situation, even if they might not have the mental capacity to add to the complexity of the debates taking place. They still had a purpose in the midst of Kingdom conversation according to Yeshua. In fact, the text tells us He took offense at the actions of His students, reprimanding them unabashedly in front of everyone present, and then interrupted His teaching with the religious elite to embrace and to bless these very children. Not only this, but He used the time to speak of the spiritual worth of a child’s character. The value inherent in a young mind, not so thoroughly tainted by the wiles of this world, was something that Yeshua lauded as important for us all to somehow retain as we age or regain if it be lost.

This glowing sentiment is not the only time Messiah made note of the meaningfulness of a youth within the Kingdom of the Holy One. In Matthew 18:1-5, He is recorded as making a similar statement about the virtue a child possesses and how it is a necessary component in the Kingdom of Heaven.

This glowing sentiment is not the only time Messiah made note of the meaningfulness of a youth within the Kingdom of the Holy One. In Matthew 18:1-5, He is recorded as making a similar statement about the virtue a child possesses and how it is a necessary component in the Kingdom of Heaven.

1 In that hour drew near the students unto Yeshua, and were saying, “Who, indeed, is the greatest in the Kingdom of the Heavens?”

2 And Yeshua called a young boy and stood him between them,

3 and said, “Surely I say to you that if you do not be changed and become as youths, you shall not enter to the Kingdom of the Heavens!

4 He, therefore, who humbles his soul as this youth – he shall be greatest in the Kingdom of the Heavens!

5 And he who shall receive [those] like this youth in My name, Me he receives!

2 And Yeshua called a young boy and stood him between them,

3 and said, “Surely I say to you that if you do not be changed and become as youths, you shall not enter to the Kingdom of the Heavens!

4 He, therefore, who humbles his soul as this youth – he shall be greatest in the Kingdom of the Heavens!

5 And he who shall receive [those] like this youth in My name, Me he receives!

It is important to make note of His words about the part children play in the Kingdom, and how we must of needs adopt that same purity and humility if we desire to have our own portion in the Messianic world that is coming upon us all. Yeshua’s view of children is uniquely high and worthy of appreciation. But in order to do that, we need to go in somewhat of an odd direction for the next part of this study. It might seem like a complete detour, but it will make sense of Messiah’s perspective of the heavenly significance of a child when we understand this next detail.

In order to rightly appreciate Yeshua’s words about the spiritual significance of children, we must discuss first the work of the scribe.

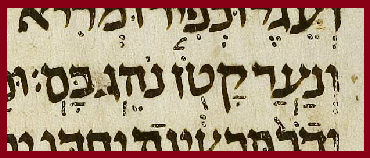

Biblically, scribes are largely misunderstood. They often are recognized due to being seen in the company of Yeshua’s antagonists, usually paired with the Pharisees or the priests who sought to test the validity of the rogue rabbi from the wild northern lands of Galilee. For this reason, they are typically viewed with disdain. Scribes are mentioned in scattered references throughout the Hebrew Scriptures, and several are even named in those books. Even though they are usually viewed through the lens of how they are often introduced in their interactions with Yeshua in the Gospels, upon closer inspection, it is understood that the scribes were the human instruments used to preserve and promulgate the Word of the Holy One. It was their high calling and lifelong duty to relay the inspired Text in a pure and reliable transmission, ensuring the passing-on of the faith to the next generation. We owe so much of our faith, as well as the shaping of our religious history, to these men whose names were seldom even recorded for history.

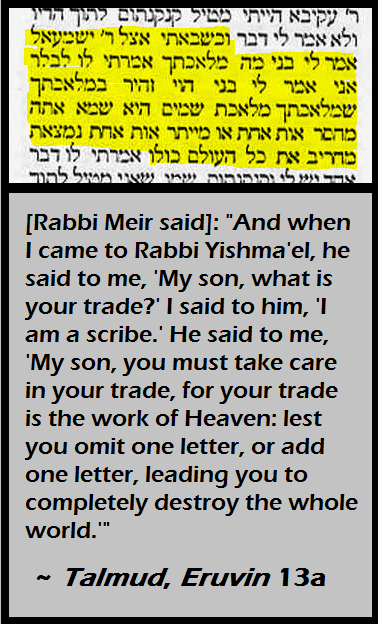

The scribe is tasked with copying, and copying, and copying yet again the eternal Word of the Holy One. Whether it be for grand and awesome scrolls of Scripture, or for the passages inserted into tefillin and mezuzot, or the writing of marriage contracts or divorce certificates, the scribe is burdened with correctly expressing the holy texts at his fingertips. Mistakes in that trade are grievous and can hold severe spiritual consequences. In fact, the Talmud Bavli, in tractate Eruvin 13a, records the words spoken to one scribe that are entirely sobering.

In order to rightly appreciate Yeshua’s words about the spiritual significance of children, we must discuss first the work of the scribe.

Biblically, scribes are largely misunderstood. They often are recognized due to being seen in the company of Yeshua’s antagonists, usually paired with the Pharisees or the priests who sought to test the validity of the rogue rabbi from the wild northern lands of Galilee. For this reason, they are typically viewed with disdain. Scribes are mentioned in scattered references throughout the Hebrew Scriptures, and several are even named in those books. Even though they are usually viewed through the lens of how they are often introduced in their interactions with Yeshua in the Gospels, upon closer inspection, it is understood that the scribes were the human instruments used to preserve and promulgate the Word of the Holy One. It was their high calling and lifelong duty to relay the inspired Text in a pure and reliable transmission, ensuring the passing-on of the faith to the next generation. We owe so much of our faith, as well as the shaping of our religious history, to these men whose names were seldom even recorded for history.

The scribe is tasked with copying, and copying, and copying yet again the eternal Word of the Holy One. Whether it be for grand and awesome scrolls of Scripture, or for the passages inserted into tefillin and mezuzot, or the writing of marriage contracts or divorce certificates, the scribe is burdened with correctly expressing the holy texts at his fingertips. Mistakes in that trade are grievous and can hold severe spiritual consequences. In fact, the Talmud Bavli, in tractate Eruvin 13a, records the words spoken to one scribe that are entirely sobering.

One single mistake could potentially spell (literally) disaster for the reader, and that mistake could then be passed on and on through the years, damaging all manner of faiths who read the erroneous in the process. Even just a minor misreading here or there would possibly mean incorrect truths being spread about the will of the Most High for His people. The words spoken to Rabbi Meir in the above Talmudic quote thus should not be taken lightly. A scribe must be careful to record the texts he has been authorized to produce with the utmost focus and accuracy. Attention to the holy text and precision in copying are vital traits to maintain in the scribe’s trade.

Additionally, it is a scribe’s duty to also analyze the works of those who came before, to assess them and render judgment that what is presented as the pure Word of the Holy Spirit is indeed trustworthy and authorized to be read by a believer with no worry about potentially being misled by a false reading somewhere. The Hebrew text of Scripture is just that important in the realm of true faith. Failure to rightly present the Word by even one mistake renders a holy text invalid for use by a believer! Therefore, if a mistake is found, it must be corrected so that the text can be used for its intended purpose of bringing people knowledge of the truth.

Yet, it is here where things can get tricky. As a scribe is tasked with producing new work and assessing what has already been written, errors in a text will inevitably appear, unfortunately. When such errors are encountered, it is the duty of the scribe to very carefully correct the problematic issue. There are several ways that this can be met, from scratching out the letter and rewriting, to cutting the erroneous reading out, to carefully lifting a thin layer of the parchment itself away with the erroneous part.

Additionally, it is a scribe’s duty to also analyze the works of those who came before, to assess them and render judgment that what is presented as the pure Word of the Holy Spirit is indeed trustworthy and authorized to be read by a believer with no worry about potentially being misled by a false reading somewhere. The Hebrew text of Scripture is just that important in the realm of true faith. Failure to rightly present the Word by even one mistake renders a holy text invalid for use by a believer! Therefore, if a mistake is found, it must be corrected so that the text can be used for its intended purpose of bringing people knowledge of the truth.

Yet, it is here where things can get tricky. As a scribe is tasked with producing new work and assessing what has already been written, errors in a text will inevitably appear, unfortunately. When such errors are encountered, it is the duty of the scribe to very carefully correct the problematic issue. There are several ways that this can be met, from scratching out the letter and rewriting, to cutting the erroneous reading out, to carefully lifting a thin layer of the parchment itself away with the erroneous part.

Sometimes, however, a unique situation presents itself, because the Hebrew alphabet is written in such a way that certain letters visually appear remarkably similar to others. Because of this similarity in form, in some situations there is actual doubt when it comes to whether or not an error was made by the scribe when a letter was originally written. This means a scribe might not always be able to judge for certain what letter the former scribe intended to write if it has features that too-closely resemble another letter. The laws governing a scribe are such that one must correct an error found in a text. But a scribe is also not allowed to destroy a letter in a holy text that is potentially valid and acceptable. In a situation where doubt exists as to whether or not a letter was written in error or is in fact the letter as it should appear in that respective place in the text, then the scribe has the dilemma of what must be done. He cannot destroy a potentially valid letter, but he also cannot allow a potentially invalid letter to remain, as it invalidates the entire holy text from being used in any further religious manner.

Five examples of such truly problematic situations are given here so the reader can appreciate just what a scribe is confronted with at these times, and how serious a matter trying to arrive at a conclusion on these things can be. In fact, each of the following examples given were shared by actual scribes who were themselves uncertain about what to do, and so these examples were shared with other scribes to arrive at a consensus of action.

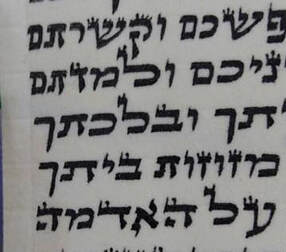

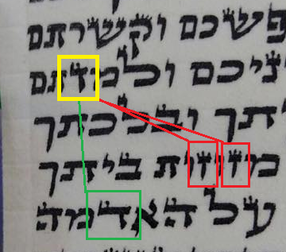

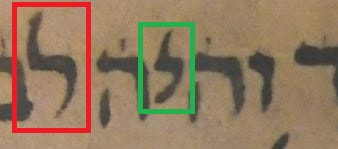

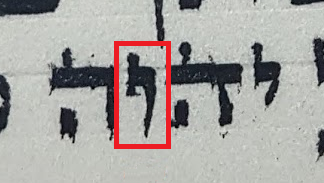

The first example is from one of the scrolls that are placed inside the leather head-piece the Torah commands us to wear called tefillin shel rosh (tefillin for the head), specifically the scroll with the passage from Deuteronomy 11:13-21. Look closely at the second word from the top on the left side. It is supposed to be the word VELIMMADETEM “and you shall teach.” However, there is an uncertainty concerning the identification of one of the letters in the word.

The letter in question is highlighted in yellow in the following photo. It is supposed to be the letter Dalet, an example of which is shown highlighted in green in the same scroll, but it looks also similar to the letter Zayin, two of which have been highlighted in red in the same photo.

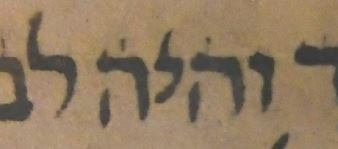

The second example comes from a scroll of the Torah, specifically from Exodus 30:16. The term of importance is the word VEHAYAH “and it shall be.”

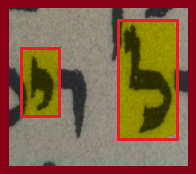

The letter in question should be the letter Yud, highlighted in green in the accompanying image. However, it looks like it could possibly be a minuscule version of the letter Lamed, which I have highlighted in red.

In order to see how similar the questionable letter Yud in the passage above really is in that instance, I have shared an image with the two letters written correctly and in close proximity so the reader can see exactly how they should appear in written form.

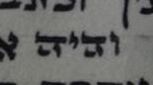

A third example comes from a mezuzah scroll, which is placed inside a container and attached to the doorpost of a believer’s home. The specific passage shown comes from Deuteronomy 11:13, and the word should be VEHAYAH “and it shall be.”

While this is the same word (albeit in a different passage) as discussed in the previous example, the issue here is entirely different. The letter Heh almost looks like it could be the letter Gimel. I have highlighted the letter Heh in red in the accompanying image.

A clearly-defined space should exist at the bottom of letter, as the clearly-written letter Heh to the left of the one highlighted in red shows well. To be sure, if the letter is zoomed-in upon, there is indeed a tiny gap where a gap should exist, so it is technically written correctly, but visually, it could be easily confused for a letter Gimel, which makes for a valid issue regarding doubt when read. The accompanying image shows a comparison of a letter Heh and a letter Gimel from a different location in a Torah scroll so that the reader can see them clearly distinguished.

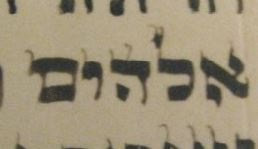

A fourth example is from a Torah scroll. It centers on the holy title ELOHIM “Deity,” as it is found in Genesis 9:16.

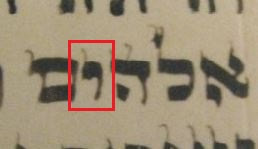

In this case, it is the presence of the letter Yud whose identity was of uncertain intention. The letter is highlighted in red in the accompanying image.

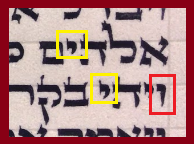

The question was whether or not the letter Yud looked too similar to the letter Vav. I have highlighted letters from another scroll of Torah in order to showcase the distinction between the two letters. In the accompanying image, the letter Yud is highlighted in yellow, while the letter Vav is highlighted in red.

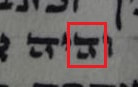

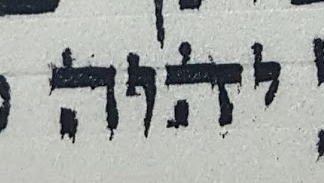

The fifth and final example I will share comes again from a scroll inserted into a tefillin, specifically from Deuteronomy 11:21. The word in question is the Divine Name of the Most High- the Tetragrammaton.

The problematic letter should be the letter Vav, but it is written in such a way that it could possibly be mistaken for a Peh Sofit, that is, the form of the letter Peh as it appears at the end of a word.

I have highlighted the two letters from another place in a Torah scroll to show how distinct they should appear. The letter Vav is in green, and the letter Peh Sofit is highlighted in red.

Based just on these five examples from the many that scribes run across in their trade, the reader can see the quandary of what must be done is sometimes entirely legitimate.

What is a scribe to do?

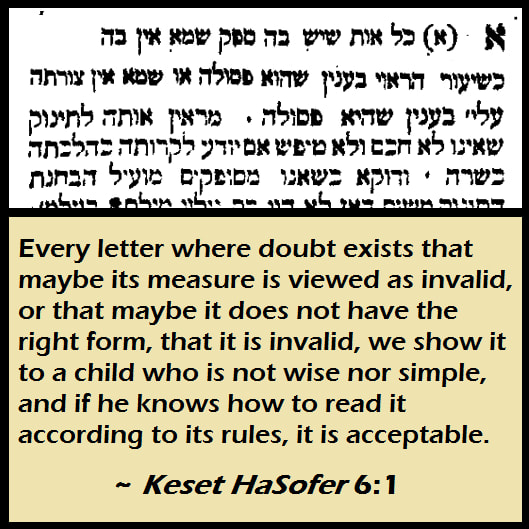

Thankfully, scribes rely on ancient traditions for almost every step in the process of creating and proofreading holy texts. This is no less the case for a situation like this. The ancient method is revealing, and the scribe can rely on such a ruling as found in the scribal guidebook called Keset HaSofer 6:1, which describes the ancient Jewish method passed down over millennia for what to do when there is doubt about the identity of a letter in a holy text.

What is a scribe to do?

Thankfully, scribes rely on ancient traditions for almost every step in the process of creating and proofreading holy texts. This is no less the case for a situation like this. The ancient method is revealing, and the scribe can rely on such a ruling as found in the scribal guidebook called Keset HaSofer 6:1, which describes the ancient Jewish method passed down over millennia for what to do when there is doubt about the identity of a letter in a holy text.

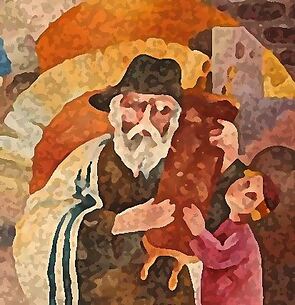

This method of arriving at an answer is typically referred to among scribes as HAVCHANOT TINOK “discretion of a child,” or SHAILOT TINOK “questioning a child.” We see from this rule that the examples shared above from several different scribes show that there are times where a scribe is legitimately at a loss for how to proceed, and so a child’s discretion is the only way to handle a questionable letter in such an instance. Additionally, there are certain methods by which the question is put to the child, in order for the youth to not be led to assume one way or the other based on the context of the passage in which the letter is located. But this truly is the method used by scribes to decide a point of doubt concerning the correct identification of a letter written in a holy text.

This ruling shows us that the pure and humble witness of a small child can determine whether or not a scroll of Scripture is indeed valid for use by a community of believers. Think about the ramifications of this for a moment. A highly educated scribe, one who is learned thoroughly in all the minutiae of what constitutes the holy text being properly transmitted to the next generation, at times will be faced with a decision for which all of his learning and refining still leaves him totally inadequate to move forward. For all of his discipline, he is left without the means to rightly judge the legitimacy of the text before him. The only acceptable course of action is to turn to a child who typically is not even at the age where their reading comprehension skills are formally developed but can at least recognize letters of the Hebrew alphabet enough to make correct judgments concerning what letter is before them.

This ruling shows us that the pure and humble witness of a small child can determine whether or not a scroll of Scripture is indeed valid for use by a community of believers. Think about the ramifications of this for a moment. A highly educated scribe, one who is learned thoroughly in all the minutiae of what constitutes the holy text being properly transmitted to the next generation, at times will be faced with a decision for which all of his learning and refining still leaves him totally inadequate to move forward. For all of his discipline, he is left without the means to rightly judge the legitimacy of the text before him. The only acceptable course of action is to turn to a child who typically is not even at the age where their reading comprehension skills are formally developed but can at least recognize letters of the Hebrew alphabet enough to make correct judgments concerning what letter is before them.

Such a child as this holds the only key forward in this matter of the Kingdom.

Whatever the child affirms the letter in question to be is taken as a judgment full of veracity, and only then is action able to be taken by the scribe – if any is even needed at that point. If the child sees the letter as the correct letter, nothing is done – it is a valid presentation of the text and is therefore deemed a kosher text. If the child reads instead the letter as something that should not be present at that point of the text, then the letter can be dealt with as necessary by the scribe’s resources, and the text restored to a valid holy text. But it is the child alone who possesses the spiritual purity and humility at that point to reconcile what seems like an impossible situation for the skill of the scribe. While an apparent contrast seems to exist in a single letter, the child has the simplicity of insight to judge what the letter’s inherent worth really is, and is therefore able to bring peace to the situation by utilizing a value not even the scribe, in all his learning and desire for correctness, could provide.

Whatever the child affirms the letter in question to be is taken as a judgment full of veracity, and only then is action able to be taken by the scribe – if any is even needed at that point. If the child sees the letter as the correct letter, nothing is done – it is a valid presentation of the text and is therefore deemed a kosher text. If the child reads instead the letter as something that should not be present at that point of the text, then the letter can be dealt with as necessary by the scribe’s resources, and the text restored to a valid holy text. But it is the child alone who possesses the spiritual purity and humility at that point to reconcile what seems like an impossible situation for the skill of the scribe. While an apparent contrast seems to exist in a single letter, the child has the simplicity of insight to judge what the letter’s inherent worth really is, and is therefore able to bring peace to the situation by utilizing a value not even the scribe, in all his learning and desire for correctness, could provide.

All of this shows us that the view Yeshua expressed towards children is one where He too appreciated the special role they have to play in the spiritual landscape of the Kingdom. Yeshua’s words were spoken with an understanding of the vital service a young person can provide the faithful in our shared walk before the Holy One. A child has the potential authority to make serious and binding spiritual judgments that affect the community of believers. They are not to be dismissed as lower on a spiritual-worth scale. Even in the midst of challenging religious debate and discussion of the minutiae of the holy text, a child just might have a part to play that no adult can resolve!

This element of usefulness within the Kingdom of believers is something hinted at elsewhere in Scripture, in the book of Isaiah. In the 11th chapter, the prophet records wonderful expressions of what the Messianic era is like. Familiar language is encountered there of what life will be like for the citizens of the Kingdom. We find the wolf resting with the lamb, the leopard with the kid, and so forth. And then, at the end of 11:6, we read a concluding expression about that very situation.

This element of usefulness within the Kingdom of believers is something hinted at elsewhere in Scripture, in the book of Isaiah. In the 11th chapter, the prophet records wonderful expressions of what the Messianic era is like. Familiar language is encountered there of what life will be like for the citizens of the Kingdom. We find the wolf resting with the lamb, the leopard with the kid, and so forth. And then, at the end of 11:6, we read a concluding expression about that very situation.

…and a little boy shall lead them.

The authority of a child in the Messianic era is here displayed in a poetic manner. When predator and prey can exist in harmony, true resolution has come. It is a child who is the one leading this astounding situation! The imagery is poetic and beautiful, but the intent is clear: a child will know how to deal with a seemingly impossible situation and bring a compatibility when it otherwise would make no sense. The context perfectly aligns with the path the scribe must take when confronted with a letter of uncertain identification: only a child’s faith can bring peace to the scribe’s inconclusive appraisal of the situation.

This prophecy from Isaiah 11:6, as well as the viewpoint of Yeshua towards the worth of children in the Kingdom of the Holy One, could even be said to be exemplified in a situation recorded to have occurred in His own life. The Gospel of Luke preserves an event that happened to Yeshua when He was but a young child, as well: His parents inadvertently left Him behind in Jerusalem after the celebrations of Passover, thinking He was in attendance with their caravan as it descended back into the northern frontiers of Galilee. However, not only was the youthful Yeshua still in Jerusalem, He ended up spending His time away from family in the presence of the Torah scholars, priests, and scribes who sat in the Temple and expounded upon the nuances of Holy Writ. Luke 2:46-47 tells us the relevant information.

This prophecy from Isaiah 11:6, as well as the viewpoint of Yeshua towards the worth of children in the Kingdom of the Holy One, could even be said to be exemplified in a situation recorded to have occurred in His own life. The Gospel of Luke preserves an event that happened to Yeshua when He was but a young child, as well: His parents inadvertently left Him behind in Jerusalem after the celebrations of Passover, thinking He was in attendance with their caravan as it descended back into the northern frontiers of Galilee. However, not only was the youthful Yeshua still in Jerusalem, He ended up spending His time away from family in the presence of the Torah scholars, priests, and scribes who sat in the Temple and expounded upon the nuances of Holy Writ. Luke 2:46-47 tells us the relevant information.

46 And from after three days, they found Him in the Temple, where He was sitting among teachers, and was listening to them, and was inquiring of them.

47 And all those who were hearing Him were stupefied by His wisdom and by His sayings.

We see from this that Yeshua experienced His own youthful moment of merit in the midst of holy men. Rather than shoo Him away as a bothersome child, they welcomed Him into the learning environment, inadvertently partaking in the prophetic words from Isaiah 6:11. By doing so, those who were themselves learned and taught in the intricacies of the Torah ended up being astonished at the leading of this young boy who did not seem old enough to have attained the wisdom and spiritual insight He must have been displaying so freely to them all. This incident frames well the entirety of this study: a child has a part to play in the holy atmosphere of the Kingdom. Yeshua’s own example and His words while ministering exemplify this wonderful truth.

The Messiah’s opinion and actions towards the young children, and His subsequent words of affirmation of their spiritual traits, and our own need to somehow return to that level of purity and soundness in judging the things of the Spirit cannot be downplayed. There comes points in the lives of every believer where education and knowledge will only allow us so far in the things of the Kingdom. At that moment, all our sincere learning will do us no further good. We must rely then upon a purer trait – a humility to acknowledge that although there is essentially a whole realm of unknown truth for us, we can still act for Him in the humble place we find ourselves in at that precise moment. Just as Yeshua did not forbid the children based on their lack of legal expertise in the Torah, but instead embraced them for the value they already possessed to the Kingdom, so too should we realize where our true value before Him lay.

With His trustworthy leading in place, we can rightly apply the faith we have been given to be of merit in the key spiritual matters of the Kingdom of heaven. We would do well to meditate upon this intricate detail and pray that our own hearts will be made worthy to act in such high value in the significant spiritual things of the Kingdom – just as are the hearts of those young people in our midst. If of such is these is the Kingdom of Heaven, let us do whatever is necessary to be able to be as they are!

With His trustworthy leading in place, we can rightly apply the faith we have been given to be of merit in the key spiritual matters of the Kingdom of heaven. We would do well to meditate upon this intricate detail and pray that our own hearts will be made worthy to act in such high value in the significant spiritual things of the Kingdom – just as are the hearts of those young people in our midst. If of such is these is the Kingdom of Heaven, let us do whatever is necessary to be able to be as they are!

All study contents Copyright Jeremy Chance Springfield, except for graphics and images, which are Copyright their respective creators.