ISAAC'S SHIN

by Jeremy Chance Springfield

4/18/18

Isaac, the son of Abraham, is a rather iconic figure in Scripture. He is the cherished son of the promise, obedient unto the brink of death at the hand of Abraham. He is the husband of Rebecca. He is the father of Esau and Jacob. However, of the three patriarchs, the least amount of the Torah is devoted to his life story, and he is mentioned throughout Scripture the least of the patriarchs. His father Abraham and his son Jacob receive more attention and spotlight than Isaac by far. Although the least focused upon of the three patriarchs of our faith, Isaac is yet the center and the surety of the promise made to our father Abraham.

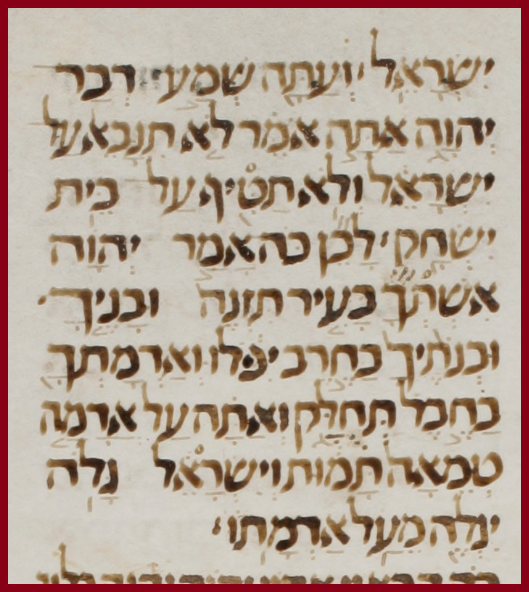

There are two rather unique aspects about Isaac that I assert make him stand out from the other two patriarchs in a definitely memorable way. The first is that he is the only one of the patriarchs who was tied absolutely to the land of promise, never leaving the borders of the inheritance as his father and his son ended up doing in their wandering lives. Genesis 26:2-6 gives us that information:

There are two rather unique aspects about Isaac that I assert make him stand out from the other two patriarchs in a definitely memorable way. The first is that he is the only one of the patriarchs who was tied absolutely to the land of promise, never leaving the borders of the inheritance as his father and his son ended up doing in their wandering lives. Genesis 26:2-6 gives us that information:

2 And YHWH appeared to him, and said, “Do not descend to Mitzrayim; dwell in the land which I tell you.

3 Sojourn in this very land, and I shall be with you, and I shall bless you, for to your and to your seed I shall give all this land. And I shall make firm the oath that I swore to Avraham your father,

4 and I shall increase your seed as the stars of the heavens, and shall give to your seed all this land, and all the peoples of the earth shall be blessed in your seed,

5 because of Avraham: he heard My voice, and he guarded My charge, My commandments, My statutes, and My instructions.”

6 And Yitzkhaq dwelt in Gerar.

3 Sojourn in this very land, and I shall be with you, and I shall bless you, for to your and to your seed I shall give all this land. And I shall make firm the oath that I swore to Avraham your father,

4 and I shall increase your seed as the stars of the heavens, and shall give to your seed all this land, and all the peoples of the earth shall be blessed in your seed,

5 because of Avraham: he heard My voice, and he guarded My charge, My commandments, My statutes, and My instructions.”

6 And Yitzkhaq dwelt in Gerar.

The second aspect that makes Isaac unique among the patriarchs is that he is also the only one of the patriarchs who did not receive a change in his name by the Holy One. Abram his father was renamed Abraham, and Isaac’s son Jacob was renamed Israel. But the Holy One did not rename Isaac.

Upon looking at the matter closer, though, we find an intriguing detail at play in this aspect. In the Hebrew Scriptures, his name appears one hundred and eight different times. Of those many appearances, four of them are of particular interest, because they possess in them an oddity of spelling that should make one pause and take notice. Although the Holy One did not change the name of Isaac during his lifetime, as he did Abraham and Jacob, He did preserve a special alternate form of his name later in the text of Scripture. The unique spelling deserves attention and further investigation, for it is directly related to the fact that Isaac stayed upon the land of promise that was covenanted to Him and his seed, due to the obedience of Abraham to the commands and statutes of the Holy One.

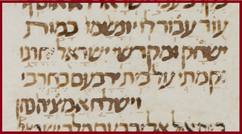

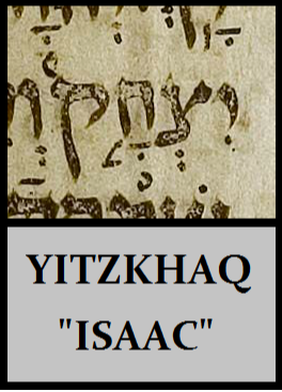

However, before we get into the strange variant form of Isaac’s name, let us take a moment and appreciate the name of Isaac as it is normally and overwhelmingly given in the Hebrew tongue: Yitzkhaq. For phonetic clarity, pronounce it as: YEETZ-KHAWQ. The name in Hebrew simply means “He shall laugh,” and refers to the response given by his mother Sarah when she first heard she would bare a child in her late age to Abraham in fulfillment of the promise [see Genesis 18:12-13,15]. The name is spelled in the Hebrew letters as Yod-Tzadi-Khet-Qof, as the image from this ancient manuscript shows.

Upon looking at the matter closer, though, we find an intriguing detail at play in this aspect. In the Hebrew Scriptures, his name appears one hundred and eight different times. Of those many appearances, four of them are of particular interest, because they possess in them an oddity of spelling that should make one pause and take notice. Although the Holy One did not change the name of Isaac during his lifetime, as he did Abraham and Jacob, He did preserve a special alternate form of his name later in the text of Scripture. The unique spelling deserves attention and further investigation, for it is directly related to the fact that Isaac stayed upon the land of promise that was covenanted to Him and his seed, due to the obedience of Abraham to the commands and statutes of the Holy One.

However, before we get into the strange variant form of Isaac’s name, let us take a moment and appreciate the name of Isaac as it is normally and overwhelmingly given in the Hebrew tongue: Yitzkhaq. For phonetic clarity, pronounce it as: YEETZ-KHAWQ. The name in Hebrew simply means “He shall laugh,” and refers to the response given by his mother Sarah when she first heard she would bare a child in her late age to Abraham in fulfillment of the promise [see Genesis 18:12-13,15]. The name is spelled in the Hebrew letters as Yod-Tzadi-Khet-Qof, as the image from this ancient manuscript shows.

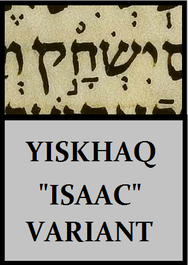

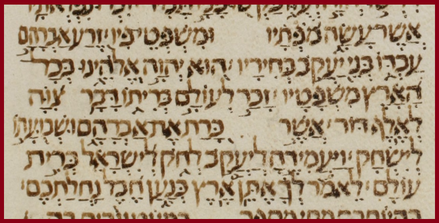

The alternate spelling that is encountered in Scripture of Isaac’s name is still very similar in many respects, but it is also markedly different. Typically, an English translation of the Hebrew Bible will not even bother to display the textual reality of the subtle difference contained in the alternately-spelled form, so it is usually not even able to be noted by readers unless one is reading from the actual Hebrew text itself. In the Hebrew tongue it is pronounced: Yiskhaq. This version of the name is spelled in the Hebrew letters as Yod-Shin-Khet-Qof, as the image from this ancient manuscript shows.

The phonetic difference between Yitzkhaq and the variant Yiskhaq is certainly minimal. Yet, the distinction that exists is worth noting. The overwhelming use of Yitzkhaq and the surprising few appearances of Yiskhaq merit taking the time to see what might be going on that is deeper than mere phonetic disparity. The only difference between the two versions is the inclusion / omission of the Hebrew letters Tzadi and Shin.

The letter Tzadi in Hebrew is pronounced essentially exactly the same as the way the letters “zz” are pronounced in the English word pizza. The Tzadi is thus a TZa or TSa sound on the tongue. The letter Shin in Hebrew is pronounced either as a SH sound as in shy, or else, if referred to as the letter Sin, as a simple letter S sound as in say.

The letter Tzadi in Hebrew is pronounced essentially exactly the same as the way the letters “zz” are pronounced in the English word pizza. The Tzadi is thus a TZa or TSa sound on the tongue. The letter Shin in Hebrew is pronounced either as a SH sound as in shy, or else, if referred to as the letter Sin, as a simple letter S sound as in say.

What is interesting to note in all of this is that the root word behind Isaac’s name is the term TZAKHAQ, meaning “laugh” in Hebrew. The addition of a single letter Yod to the beginning of the term conjugates the word into an imperfect masculine form: “he shall laugh.” It is a term used in such conjugation three different times in Hebrew Scripture where it does not refer to Isaac as Yitzkhaq, but appears in the context of a passage as a simple verb. Consequently, the Hebrew term SAKHAQ, spelled with a Shin as a Sin (S sound), also means “laugh.” The addition of a single letter Yod to the beginning of the term conjugates the word into an imperfect masculine form: “he shall laugh.” It is a term used in such conjugation seven different times in Hebrew Scripture where it does not refer to the alternate form for Isaac of Yiskhaq, but appears in the context of a passage as a simple verb.

This information tells us that the variant form of the word “laugh” was known and in use in Hebrew as prevalently as the typical word behind Isaac – so why does it appear only in four instances in all of Scripture? Why the variant name change at all? This is where I think it gets very interesting, because we have the opportunity to look at the text of Scripture with eyes anew and seek the wisdom of the Spirit behind the choice of using the variants. There are two main ways we can approach the variant spelling by looking at it in a slightly different fashion.

The first way of looking at this unique version of Yiskhaq for Isaac is to return once more to the root of the term in this alternate spelling. I have explained that the term SAKHAQ means “laugh,” but since the term is spelled with the letter Shin, one could just as legitimately pronounce it via the SH rendering instead of the S of the Sin rendering, to yield: SHAKHAQ. Why would this be a possible rendering? Originally written as such, and even today in Torah scrolls worldwide, there is no visual distinction between knowing to pronounce the letter Shin as if it were intended to be a Shin SH sound, or if it were intended to be a Sin S sound. Over time, in writing the letter, a dot came to be placed over the right-most arm of the letter to designate it be pronounced as a Shin SH sound, or else a dot would be placed over the left-most arm of the letter to designate it be pronounced as Sin S sound. Since such did not originally distinguish the letter, it is absolutely viable in our investigation of the alternate spelling of Yiskhaq to look at the root as coming from SHAKHAQ instead of the assumed SAKHAQ “laugh” source. Doing this allows us to see something truly of interest. Therefore, if we read the word as if it were SHAKHAQ, we find that a whole new root concept emerges: “dust” and / or “cloud.”

The secondary way we can approach the variant spelling of the name Isaac is by ignoring that contestable letter of difference altogether, so that the Tzadi and Shin/Sin question is effectively left out of pronouncing the variant name entirely. If there is a question as to why it is different, perhaps if we remove completely that very source for questioning, a new insight could be gained in the entire matter. In doing this, instead of reading the term in the Hebrew as Yitzkhaq (Yod-Tzadi-Khet-Qof), or as Yiskhaq (Yod-Shin-Khet-Qof), the result is to read the term as if it were spelled the word Yukhaq (Yod-Khet-Qof), which in Hebrew has the definition of: “to inscribe.”

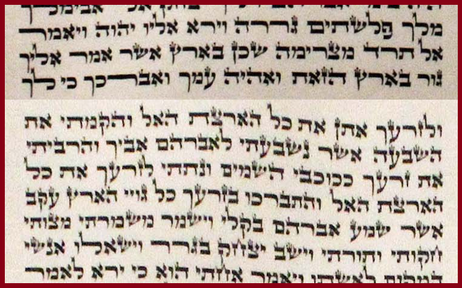

If we look at the variant form of Yiskhaq with the idea of Yishkhaq “dust” in mind, and also with the idea of Yukhaq “to inscribe” in mind, then we can approach the passages with that unique version and hopefully begin to see what the Spirit was attempting to say in those places. The first passage we find the name in is in Psalms 105:6-11, where we read this:

6 Seed of Avraham, His servant, sons of Yaaqov, His chosen:

7 He is YHWH our Elohim; in all the earth are His judgments.

8 He remembered forever His covenant, the word commanded to a thousand generations,

9 which He cut with Avraham, and His oath to Yiskhaq,

10 and established it to Yaaqov for a statute; to Yisra’El a covenant forever,

11 saying, “To you I give the land of K’naan, the measure-line of your inheritance.”

7 He is YHWH our Elohim; in all the earth are His judgments.

8 He remembered forever His covenant, the word commanded to a thousand generations,

9 which He cut with Avraham, and His oath to Yiskhaq,

10 and established it to Yaaqov for a statute; to Yisra’El a covenant forever,

11 saying, “To you I give the land of K’naan, the measure-line of your inheritance.”

The concept of SHAKHAQ “dust” can be seen in this passage in that the text speaks of the Creator being “in all the earth,” and that the covenant made with the descendants of Abraham is to give us “the land” of Canaan itself!

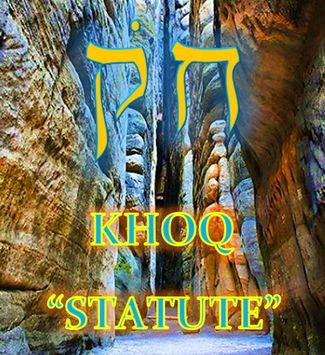

The concept of YUKHAQ “to inscribe” can be seen in this passage in that the text mentions His covenant being “cut” with Abraham, and established as a “statute” with Jacob. The “inscribing” is linked to the very notion of “statute,” too, which is KHOQ in Hebrew – the root of the word Yukhaq “to inscribe!”

The concept of YUKHAQ “to inscribe” can be seen in this passage in that the text mentions His covenant being “cut” with Abraham, and established as a “statute” with Jacob. The “inscribing” is linked to the very notion of “statute,” too, which is KHOQ in Hebrew – the root of the word Yukhaq “to inscribe!”

Therefore, the presence of the form of Yiskhaq in the text is telling us something about the covenant of the land, which He has given to us by inscribing it as a statute forever. This significant detail is only arrived at when we look deeper into the unique version of Yiskhaq. However, this is only the first of four appearances of that form in Scripture. The second and third is encountered in the book of Amos 7:9, 16-17.

|

…

16 And now, hear the word of YHWH: you say, “Do not prophesy against Yisra’El, and do not drop against the House of Yiskhaq!” 17 Therefore, thus says YHWH, “Your wife in the city shall be a prostitute, and your sons and your daughters by a sword shall fall, and your land with a measure-line shall be divided, and you upon an unclean land shall die, and Yisra’El shall certainly be exiled from upon his land.” |

These two instances come within the context of judgment. This lowly prophet from the southern nation of Judah was sent to the northern nation of Israel to decry their sins. The gravity of their wickedness in the land, of breaking the covenants, relegated them to a harsh judgment: exile from the land of Israel! Here we see the concepts of the importance of the descendants of Isaac as the Shakhaq “dust” of the land: their sins thus cause them to be taken to an unclean land, instead. They broke the covenants, and because of this, the punishment would be harsh. However, we should note that there is no wording present to which we can attach in any meaningful way the other concepts mined from the appearance of Yiskhaq – the concepts of Yukhaq “inscribed” and thus KHOQ “statute.” What is the reason for their absence?

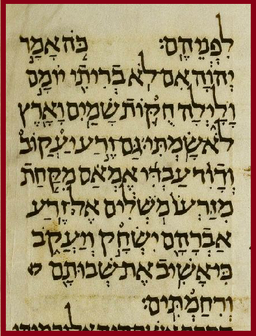

Perhaps it could be that this gloomy prophecy is lightened by a word that was to come about a century after the prophecy of Amos, to the prophet Jeremiah. He was also from Judah, but his ministry was to Judah alone, and not to Israel, and yet, still his words offer an encouragement that even such judgments against the descendants of Isaac – painful as they might be – are able to be softened with the steadfast nature of the covenant-Keeper Himself – the Holy One of Israel! In Jeremiah 33:25-26, we encounter the fourth and final appearance of Yiskhaq in the Hebrew Scriptures, where we read this information:

25 Thus says YHWH: “If My covenant were not [with] the day and night, the statutes of the heavens and earth not set,

26 then the seed of Yaaqov and David My servant I shall reject; from his seed I shall not take rulers over the seed of Avraham, Yiskhaq, and Yaaqov, for I return their captivity, and have compassion on them.”

In this instance, we again find ourselves met with a specific context: the permanency of the “statutes” and the concept of Yukhaq “to inscribe,” the “cloud” and “dust” of Shakhaq in the concept of “the heavens and the earth.” All of this is wrapped up in the giving of such to the people of Israel! Thus, we have the context preserved from the initial appearance of the form of Yiskhaq: He is faithful to His covenant to His people, which has promised us a land to dwell in before Him. Even exile and captivity can be reversed in His abounding mercies! He wants us to be where He has called us to be!

In all four appearances of the form of Yiskhaq, we have contextual tethers that go back to the initial aspect of Isaac that was mentioned of him being unique among the patriarchs: his life lived solely inside the borders of the promised land! He lived there in blessing because of the covenant, because of the statutes followed by his father, and because his presence was claim to all the land that it belonged to him and his descendants forever. His obedience merited his name be slightly altered at later times to recall the faithfulness of the Holy One to His people in the giving of the promised land. These two truly unique aspects of Isaac show us that the Most High is willing to remind us that He is faithful to His people, that even though not every one of His servants may receive the same blessings He gives others, or be as prominent as another in the record of His great plan of redemption, the promise stands for us still, if only we will heed the calling He has given us, and stand our ground for Him.

In all four appearances of the form of Yiskhaq, we have contextual tethers that go back to the initial aspect of Isaac that was mentioned of him being unique among the patriarchs: his life lived solely inside the borders of the promised land! He lived there in blessing because of the covenant, because of the statutes followed by his father, and because his presence was claim to all the land that it belonged to him and his descendants forever. His obedience merited his name be slightly altered at later times to recall the faithfulness of the Holy One to His people in the giving of the promised land. These two truly unique aspects of Isaac show us that the Most High is willing to remind us that He is faithful to His people, that even though not every one of His servants may receive the same blessings He gives others, or be as prominent as another in the record of His great plan of redemption, the promise stands for us still, if only we will heed the calling He has given us, and stand our ground for Him.

All study contents Copyright Jeremy Chance Springfield, except for graphics and images, which are Copyright their respective creators.