ANOTHER PRIEST

by Jeremy Chance Springfield

9/1/2024

One of Scripture’s overarching themes is the concept of intercession.

From nearly the beginning of Genesis and on the notion of something standing between a sin-marred man and His Creator is a truth that is repeatedly encountered in the text.

The concept is crystalized in the office of the priest.

From nearly the beginning of Genesis and on the notion of something standing between a sin-marred man and His Creator is a truth that is repeatedly encountered in the text.

The concept is crystalized in the office of the priest.

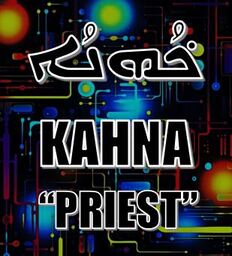

The English word “priest” ultimately arose through a progressive development originating in the Greek PRESBYTEROS “elder,” into the Latin PRESTER, and lastly into the Old English PREOST, whose spelling and pronunciation slightly morphed over time into is modern iteration.

All of this is an attempt to convey the idea of a “priest” in the Biblical sense, which is the word KOHEIN (usually presented in written form as KOHEN or COHEN).

All of this is an attempt to convey the idea of a “priest” in the Biblical sense, which is the word KOHEIN (usually presented in written form as KOHEN or COHEN).

The term in Hebrew is merely a modification of the same spelling of the word KAHAN, essentially signifying the idea of “standing up for another,” so that a priest is someone serving in the act of “advocacy” or “support” for another person—in short, a priest in the Biblical sense is inherently an intercessor.

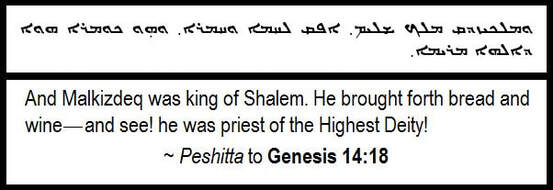

The first person every referred to in Scripture as a priest is Melchizedek, appearing in Genesis 14:18, whom Abraham met upon his successful rescue of Lot and the exiles from Sodom.

The first person every referred to in Scripture as a priest is Melchizedek, appearing in Genesis 14:18, whom Abraham met upon his successful rescue of Lot and the exiles from Sodom.

His appearance in the text is fleeting—comprising all of three verses—before the narrative resumes its focus on Abraham and his spiritual journey with the Most High. Notice, however, his actions: he brings forth bread and wine to Abraham. This detail matters in a way that might not be immediately perceived yet will be returned to later in the study after further necessary information is provided and be better appreciated at that time.

After this brief mention, Scripture also momentarily mentions pagan priests from Egypt and Midian, before concentrating almost wholly upon the priesthood found among the people of Israel that became localized in the singular tribe of Levi, as we see occurs in the book of Exodus, with primary focus on their spiritual duties detailed in the book of Leviticus.

The Levitical priesthood takes center stage as the intercessors for Israel and the rest of the world for nearly all of Scripture. They are the chosen ones to whom man must come who can lead the penitent in proper restoration before the Holy One.

The Levitical priesthood takes center stage as the intercessors for Israel and the rest of the world for nearly all of Scripture. They are the chosen ones to whom man must come who can lead the penitent in proper restoration before the Holy One.

It is only in the New Testament book of Hebrews that the idea of the priesthood is presented in a different light than that in which it had for so long shone: with the person of the Messiah surprisingly serving in the vital intercessory function! The Messiah Yeshua is declared to be another priest in thirteen different places in the book of Hebrews.

The first mention of Yeshua as a priest is encountered Hebrews 2:17.

The first mention of Yeshua as a priest is encountered Hebrews 2:17.

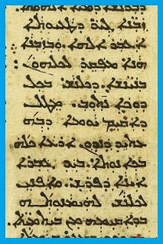

This passage clearly explains the purpose of Yeshua as a priest. Taken from the Aramaic of the Peshitta text, it is basically identical to the way Greek-based versions read. The Aramaic text is markedly different, however, in the way it refers to Yeshua as a priest. Whereas the Greek text is uniform in the word it chose to reference a “priest”—being the term HIEREUS, meaning “holy person”—the Peshitta’s Aramaic text employs two different terms for the notion of a “priest.”

The Peshitta consistently refers to a Levitical priest using the Aramaic version of the Hebrew KOHEIN, which is KAHNA.

The Peshitta consistently refers to a Levitical priest using the Aramaic version of the Hebrew KOHEIN, which is KAHNA.

Apart from this term, the far less common term for “priest” in Aramaic is KUMRA.

Besides its appearance in the book of Hebrews, KUMRA is only ever used elsewhere in the Peshitta in Acts 14:13 to refer to the pagan priest mentioned in that account. Its use for Yeshua’s unique role as a priest is thus very intriguing and worth carefully considering, for every nuance of word-choice in the inspired texts holds in it a significant teaching from which we can better appreciate the message being conveyed.

To begin our exploration of the significance of its use to describe Yeshua’s mission as a “priest,” consider first that KUMRA is the Aramaic cognate of the Hebrew term KOMER, which is only used to refer to a priest in three instances in the Hebrew Scriptures (see: 2nd Kings 23:5; Hosea 10:5; Zephaniah 1:4). A detail consistent with each of those appearances in Hebrew aligns also with the Aramaic version’s use of it in Acts 14:13—all three times it describes pagan priests.

To begin our exploration of the significance of its use to describe Yeshua’s mission as a “priest,” consider first that KUMRA is the Aramaic cognate of the Hebrew term KOMER, which is only used to refer to a priest in three instances in the Hebrew Scriptures (see: 2nd Kings 23:5; Hosea 10:5; Zephaniah 1:4). A detail consistent with each of those appearances in Hebrew aligns also with the Aramaic version’s use of it in Acts 14:13—all three times it describes pagan priests.

Knowing this historical usage of the term, why, then, would the author of Hebrews employ it when speaking solely of Yeshua’s role as a “priest?” The answer involves several aspects of note and helps us to appreciate the spiritual realities surrounding Yeshua as the Messiah Priest that are distinct from the nature of the Levitical priests.

Looking at the root concepts behind the term KOMER helps us to see the ideas that were likely involved in deciding to use it rather than those that traditionally came with the more familiar Jewish concepts tied to KAHNA / KOHEIN.

Firstly, the term KOMER has as its root the pronunciation KAMAR, which signifies something that is “blackened by heat,” and has subsequently “shrunk” or “contracted” due to its exposure to the heat source. Additionally, it is used to describe anything that has been “buried in the ground,” and is thus also used in the sense of that which has been “preserved” only by it being hidden.

These notions are important, for they all align well with the situation of Yeshua’s controversial role as the Messiah who suffered, was buried, and whose true Messianic purpose has traditionally not been understood by the majority of Israel, as we see in Isaiah 52:13-14.

Looking at the root concepts behind the term KOMER helps us to see the ideas that were likely involved in deciding to use it rather than those that traditionally came with the more familiar Jewish concepts tied to KAHNA / KOHEIN.

Firstly, the term KOMER has as its root the pronunciation KAMAR, which signifies something that is “blackened by heat,” and has subsequently “shrunk” or “contracted” due to its exposure to the heat source. Additionally, it is used to describe anything that has been “buried in the ground,” and is thus also used in the sense of that which has been “preserved” only by it being hidden.

These notions are important, for they all align well with the situation of Yeshua’s controversial role as the Messiah who suffered, was buried, and whose true Messianic purpose has traditionally not been understood by the majority of Israel, as we see in Isaiah 52:13-14.

Although some modern teachers dispute the identity of this “servant,” the ancient view as recorded in the Targum Yonatan to Isaiah 52:13 clarifies who it was who was understood as being referred to here with its illuminating phrase: AVDI MESHICHA “My servant, the Messiah.”

The text is blatantly telling us that the Messiah would not appear to be thus—to the point that when He is at last recognized as the candidate for the Messiah and be thus exalted in that role, it will be appalling to everyone.

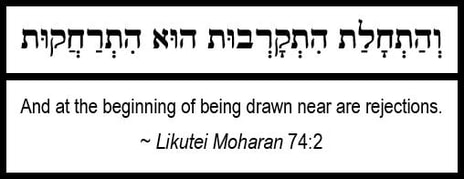

However, in order to be lifted high in a spiritual role, one must first be willing to be stripped of all honor, as the text of Likutei Moharan 74:2 explains.

However, in order to be lifted high in a spiritual role, one must first be willing to be stripped of all honor, as the text of Likutei Moharan 74:2 explains.

Anyone who will experience a lofty spiritual mission should first expect to be rejected by those who would otherwise benefit from their role.

This same concept is what happens to the Messiah, as presented in Isaiah 49:7.

This same concept is what happens to the Messiah, as presented in Isaiah 49:7.

The Servant who would intercede for all must first be willing to be rejected in that role. In Yeshua’s case, He very well holds the position of the “loathed one” of the nation of Israel, as His mission is largely misunderstood.

We see in the New Testament that Paul recognized this process of Yeshua selflessly receiving the lowest of treatment in order to be the Servant the Holy One required for the role of Messianic intercession, as stated in Philippians 2:7.

We see in the New Testament that Paul recognized this process of Yeshua selflessly receiving the lowest of treatment in order to be the Servant the Holy One required for the role of Messianic intercession, as stated in Philippians 2:7.

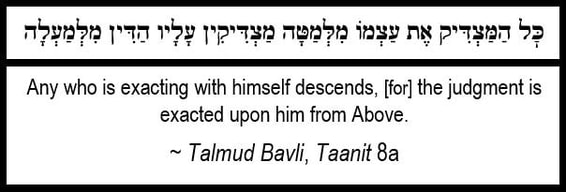

This wrecking of the Messiah has a purpose, however. The initial mistreatment and obscuration of his vital role would eventually give way to an exaltation which all will one day recognize and affirm in unity, and is even a spiritual truth stated in the Talmud Bavli, Taanit 8a.

The idea is that when the Holy One sees a person is seeking righteousness, He will bring upon the individual situations to further inculcate that righteousness--which often entails a degree of rejection or suffering to bring about. These concepts are added to the final notion of KUMRA / KOMER as a seemingly “pagan priest” to present the idea of Yeshua being an unlikely intercessor—ideas further developed in the famous words of Isaiah 53:4-5.

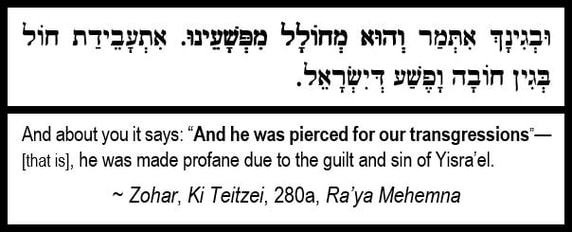

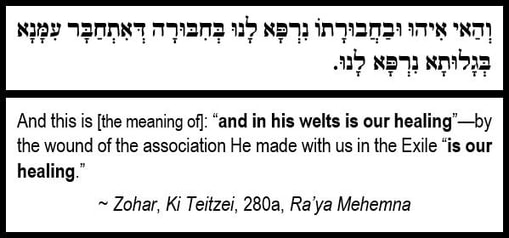

This passage, already so full of significance in the traditional rendering of the Hebrew text, has an incredible deeper meaning according to the assertion recorded in the Zohar, Ki Teitzei, 280a, Ra’ya Mehemna.

Based on the multi-faceted meaning of the Hebrew term MECHOLAL “pierced”—which can also be read as “profaned,” the Zohar presents the incredible idea that the Messiah would be made into someone who is disdainful in the eyes of Israel—all due to the sin of Israel!

This concept of a Messiah seemingly becoming something His own people would reject in order to eventually prove His true intercessory function is vital for us to understand. If we can appreciate what the Messiah as the other type of priest must go through, we can view the rejection of Yeshua by His own people through the proper lens. He is the KUMRA / KOMER—the priest who appears to be profane.

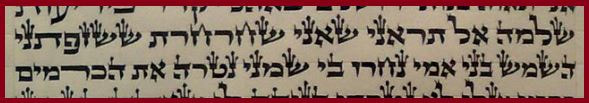

This truth is veiled in the words of The Song of Songs 1:6.

This truth is veiled in the words of The Song of Songs 1:6.

This assertion closely aligns with the root meaning behind KUMRA / KOMER—of something that has been darkened by the heat of the sun. In similar fashion, Yeshua’s willingness to accept the role appointed for Him means He must first be rejected by His own people in order to function as the other priest.

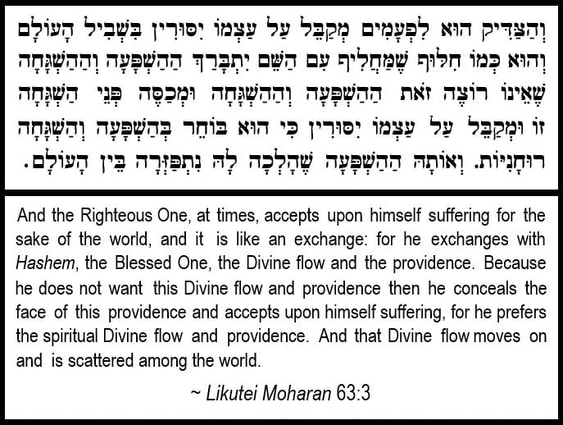

The text of Likutei Moharan 63:3 discusses this odd concept in further detail when discussing the difficulties facing the person of the Tzaddik—the “Righteous One.”

The text of Likutei Moharan 63:3 discusses this odd concept in further detail when discussing the difficulties facing the person of the Tzaddik—the “Righteous One.”

The New Testament also speaks to this seemingly backwards role of the Messiah in 2nd Corinthians 5:21.

Yeshua willingly was emptied of any self-assumed right to honor, readily allowing Himself to be brought down in the view of others, so that the benefit that could have been His would be transferred to us. This type of “descent” is priestly in nature, for it is on our behalf. Thus, Yeshua is rightly referred to as a KUMRA within the Aramaic text of the book of Hebrews, for He operates in a way that is uncanny—in seeming profane status He is really offering the world the opportunity to receive the forgiveness they need.

This is stated clearly in the text of Sefer HaMiddot, Tzaddik, Chelek Rishon 169.

This is the nature of the other priest who is not part of the Levitical priesthood: he gives of himself for those in need of atonement. In distinct contrast, the Levitical priest, while also interceding on behalf of the individual, actually receives from the person.

This takes us back to Genesis 14:18 and the initial appearance of the “priest” in the person of Melchizedek. He brings bread and wine to Abraham—he first gives of himself to the individual—which is the opposite of what happens with Levitical priests, who receive the wine for sacrifices and the grain / bread for placement on the tables in the Temple’s Holy Place.

Yeshua’s intercession is self-sacrificing: He gives of Himself first, being willing to sacrifice His own self-worth and be viewed as a reproach among His own people in order to bring the most amount of atonement to the world as is possible.

For this reason He is also connected to Melchizedek in Hebrews 5:10.

This takes us back to Genesis 14:18 and the initial appearance of the “priest” in the person of Melchizedek. He brings bread and wine to Abraham—he first gives of himself to the individual—which is the opposite of what happens with Levitical priests, who receive the wine for sacrifices and the grain / bread for placement on the tables in the Temple’s Holy Place.

Yeshua’s intercession is self-sacrificing: He gives of Himself first, being willing to sacrifice His own self-worth and be viewed as a reproach among His own people in order to bring the most amount of atonement to the world as is possible.

For this reason He is also connected to Melchizedek in Hebrews 5:10.

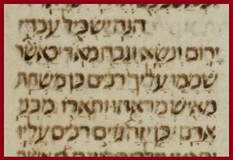

Notice that I have italicized the portion in quotes in my translation. This is because the author of Hebrews was actually quoting from the Aramaic Peshitta’s ancient version of Psalm 110:4!

This is the role Yeshua was born to inhabit—a priest who can make intercession for His people forever due to the merit of the unparalleled righteousness He possesses, which allowed Him to defeat death and put on eternal life before the Last Day when it is given to the rest of the faithful.

This we see in Hebrews 7:15-16.

This we see in Hebrews 7:15-16.

In this nature is Yeshua’s right to stand and officiate as the priest who can judge each matter of need with greater authority than all others.

The text of Likutei Moharan 74:12 comments on this special aspect of judgment and righteousness that comes when one is focused on self-sacrifice, like Yeshua, who accepted the rejection that was to come upon Him by His own people.

The text of Likutei Moharan 74:12 comments on this special aspect of judgment and righteousness that comes when one is focused on self-sacrifice, like Yeshua, who accepted the rejection that was to come upon Him by His own people.

He was willing to constrict Himself, so to speak, being emptied of consciously asserting His own rights as a Tzaddik—a Righteous One—in order to eventually stand in the proper authority as the worthy intercessor between mankind and his Maker. This is in the same context as the root meaning behind KUMRA / KOMER, which is “to contract” / “to shrink.”

Understanding these truths makes sense of why Yeshua is connected to Melchizedek as a priest. In fact, when we look at the Aramaic Peshitta’s rendering of Genesis 14:18, it becomes even clearer.

Understanding these truths makes sense of why Yeshua is connected to Melchizedek as a priest. In fact, when we look at the Aramaic Peshitta’s rendering of Genesis 14:18, it becomes even clearer.

The Aramaic text used the word KUMRA rather than KAHNA—the Aramaic cognate of the term used in the Hebrew original—KOHEIN. The ancient Jewish translators of the text understood that Melchizedek was not a Levitical priest, and so their choice of terms reflected that distinction with the word KUMRA. Melchizedek also brought forth bread and wine—which is opposite how the Levitical priest functions, since the people are to provide the grain for the bread and the wine for the altar. This displays that the unique priesthood of Melchizedek is one of self-sacrifice, of acting in a manner where the cost is paid by the priest, not the people. For the Messiah to be patterned after Melchizedek, He too must exhibit that supernal attribute of self-sacrifice.

This is the exact same function of Yeshua as the KUMRA—He gave of Himself for the benefit of Israel, suffering the disgrace.

This is the exact same function of Yeshua as the KUMRA—He gave of Himself for the benefit of Israel, suffering the disgrace.

For this reason, He has merited our total attention and complete confidence, as we see in Hebrews 12:2.

All this Yeshua did for our intercession. Because He was willing to be viewed as the profaned priest, mankind can draw near in His merit to the Holy One. This truth is embedded in the text of Isaiah 53:5, and is an insight brought forth by the Zohar, Ki Teitzei 280a, Ra’ya Mehemna.

The assertion is founded upon the Biblical term UVACHAVURATO “and in his welts.” It is from the term CHAVURAH, which can mean a “wound” of some type, and also “associate,” or “connection” / “fellowship.”

The insight revealed in the Zohar is that Messiah connects to us through His own experience of harm. Therein is our fellowship with Him as the intercessor—for this reality goes both ways, as Paul so beautifully stated in Philippians 3:9-11, after explaining that any personal merits he may be able to rely on are nothing compared to his connection to Yeshua’s unparalleled merit.

|

9 …and I shall be found in him, while for me is no righteousness that is of my own soul, which is from the Instruction, but rather, that which is from the trust of the Messiah, which is righteousness that is from the Deity,

10 that in it I shall know Yeshua and the power of his resurrection, and shall fellowship in his sufferings, and be patterned into his death, 11 that I perhaps shall be found arriving at the resurrection that is from the house of the dead. |

The sentiment here is that of viewing Yeshua as the priest who stands in the gap for Paul and his spiritual inadequacies. Yeshua is the unique priest who is able to connect with the people on a level no Levitical priest could ever attain, and in that role, He can offer the hope no Levitical priest can give: resurrection from the dead.

It is in this light that we read the words of Acts 17:30-31.

It is in this light that we read the words of Acts 17:30-31.

|

30 For the times of error the Deity has passed away, and in this time He commands all the sons of man that every man in every place must return,

31 on account that He has appointed a day in which He is prepared to judge the earth entire with justice by the hand of that man whom He distinguished, and He shall turn every man to the trust of him in that He raised him from the house of the dead. |

Man can only go so far before the consequence of his sin must be addressed. Without intercession, man’s plight is hopeless. We need the advocacy provided by the Holy One to stand before Him in total acceptance. Reliance on our merits is no assurance.

Judgment is inevitable, but it need not be a source of fear, for when we attach ourselves to the Priest and His intercessory nature, we can trust that restoration will occur. Yeshua is that other priest who arose prior to the Levitical line, and in that broader advocacy, man has a sure hope for acceptance on the Day when we must all given an account before the Most High.

Judgment is inevitable, but it need not be a source of fear, for when we attach ourselves to the Priest and His intercessory nature, we can trust that restoration will occur. Yeshua is that other priest who arose prior to the Levitical line, and in that broader advocacy, man has a sure hope for acceptance on the Day when we must all given an account before the Most High.

All study contents Copyright Jeremy Chance Springfield, except for graphics and images, which are Copyright their respective creators.